History of Karachi

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2020) |

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Karachi |

|---|

|

| Prehistoric period |

| Ancient period |

| Classical period |

| Islamic period |

|

| Local dynasties |

| British period |

|

| Independent Pakistan |

|

The area of

Names

The ancient names of Karachi included:

Early history

Pre history

The Late

Indus Valley Civilisation

Greeks Visitors

The

Debal and Bhanbhore

Debal and Bhanbhore were the ancient port cities established near present-day modern city of Karachi. It dates back to the Scytho-Parthian era and was later controlled by Hindu Buddhist kingdoms before falling into Arab possession in the 8th century CE. In the 13th century it was abandoned Remains of one of the earliest known mosques in the region dating back to 727 AD are still preserved in the city. Strabo mentions export of rice (from near present-day Karachi and Gulf of Cambay) to Arabia.[2]

According to Biladuri, A large minaret of a temple existed in Debal whose upper portion was knocked down by Ambissa Ibn Ishak and converted into prison. and at the same time began to repair the ruined town with the stones of minaret.[3]

Post Islamic era (8th century AD – 19th century)

Muhammad bin Qasim

In AD 711,

Mughal empire

During the rule of the Mughal administrator of Sindh, Mirza Ghazi Beg the city was well fortified against Portuguese colonial incursions in Sindh. Debal and the Manora Island and was visited by Ottoman admiral Seydi Ali Reis and mentioned in his there. Fernão Mendes Pinto also claims that Sindhi sailors joined the Ottoman Admiral Kurtoğlu Hızır Reis on his voyage to Aceh. Debal was also visited by the British travel writers such as Thomas Postans and Eliot, who is noted for his vivid account on the city of Thatta.

Karak Bander

In the seventeenth century, Karak Bander was a small port on the

Kolachii

The present city of Karachi was reputedly founded as "Kolachi" by

This settlement was reputedly founded by

Kalhora dynasty

During the reign of the Kalhora dynasty the present city started life as a fishing settlement when a Balochi fisher-woman called Mai Kolachi took up residence and started a family. The city was an integral part of the Talpur dynasty in the 1720s.

The name Karachee was used for the first time in a Dutch document from 1742, in which a merchant ship de Ridderkerk is shipwrecked near the original settlement.[14][15] The city continued to be ruled by the Talpur Amir's of Sindh until it was occupied by Bombay Army under the command of John Keane on 2 February 1839.[16]

Talpur period

In the eighteenth century Karachi was occupied by the

Colonial period (1839–1947)

Company rule

After sending a couple of exploratory missions to the area, the

The arrival of troops of the Kumpany Bahadur in 1839 spawned the foundation of the new section, the military cantonment. The cantonment formed the basis of the 'white' city where the Indians were not allowed free access. The 'white' town was modeled after English industrial parent-cities where work and residential spaces were separated, as were residential from recreational places.

Karachi was divided into two major poles. The 'black' town in the northwest, now enlarged to accommodate the burgeoning Indian mercantile population, comprised the Old Town, Napier Market and Bunder, while the 'white' town in the southeast comprised the Staff lines, Frere Hall, Masonic lodge, Sindh Club, Governor House and the Collectors Kutchery [Law Court] /kəˈtʃɛri/[citation needed] located in the Civil Lines Quarter. Saddar bazaar area and Empress Market were used by the 'white' population, while the Serai Quarter served the needs of the native population.

The village was later annexed to the

The British realized its importance as a military cantonment and a port for the produce of the

In 1857, the

In 1795, the village became a domain of the

The city remained a small fishing village until the British seized control of the offshore and strategically located at

British colonialists embarked on a number of public works of sanitation and transportation, such as gravel paved streets, proper drains, street sweepers, and a network of trams and horse-drawn trolleys. Colonial administrators also set up military camps, a European inhabited quarter, and organised marketplaces, of which the Empress Market is most notable. The city's wealthy elite also endowed the city with a large number of grand edifices, such as the elaborately decorated buildings that house social clubs, known as 'Gymkhanas.' Wealthy businessmen also funded the construction of the Jehangir Kothari Parade (a large seaside promenade) and the Frere Hall, in addition to the cinemas, and gambling parlours which dotted the city.

By 1914, Karachi had become the largest grain exporting port of the

As the movement for

Post-Independence (1947 CE – present)

Pakistan's capital (1947–1958)

Karachi was chosen as the capital city of Pakistan. After the independence of Pakistan, the city population increased dramatically when hundreds of thousands of Muslim refugees from India fleeing from anti-Muslim pogroms and from other parts of South Asia came to settle in Karachi.[20] As a consequence, the demographics of the city also changed drastically. The Government of Pakistan through Public Works Department bought land to settle the Muslim refugees.[21] However, it still maintained a great cultural diversity as its new inhabitants arrived from the different parts of the South Asia. In 1959, the capital of Pakistan was shifted from Karachi to Islamabad. Karachi remained a federal territory and became the capital of Sindh in 1970 by general Yahya khan.

Cosmopolitan city (1970–1980)

During the 1960s, Karachi was seen as an economic role model around the world. Many countries sought to emulate Pakistan's economic planning strategy and one of them, South Korea, copied the city's second "Five-Year Plan" and World Financial Centre in Seoul is designed and modeled after Karachi.

The 1965 Pakistani presidential election disturbance and political movement against President Muhammad Ayub Khan started of a long period of decline in the city. The city's population continued to grow exceeding the capacity of its creaking infrastructure and increased the pressure on the city.

The 1970s saw major labour struggles in Karachi's industrial estates. During the administration of

Post 1970s–present

The 1980s and '90s also saw an influx of Afghan refugees from the Soviet–Afghan War into Karachi, and the city. Political tensions between the Muslim refugees and other groups also erupted and the city was wracked with political violence. The period from 1992 to 1994 is regarded as the bloody period in the history of the city, when the Army commenced its Operation Clean-up against the Mohajir Qaumi Movement.

Since the last couple of years however, most of these tensions have largely been quieted. Karachi continues to be an important financial and industrial centre for the Sindh and handles most of the overseas trade of Pakistan and the Central Asian countries.[

The last census was held in 1998, the current estimated population ratio of 2017 is:

- Muhajirs: 44%

- Sindhi: 8%

- Punjabi: 14%

- Pashto: 20%

- Balochi: 4%

The others include Konkani, Kuchhi, Gujarati, Dawoodi Bohra, Memon, Brahui, Makrani, Khowar, Burushaski, Arabic, and Bengali.[citation needed] Karachi is home to a wide array of non-Urdu speaking Muslim peoples from what is now the Republic of India. The city has a sizable community of Gujarati, Marathi, Konkani-speaking refugees. Karachi is also home to a several-thousand member strong community of Malabari Muslims from Kerala in South India. Karachi is the largest Bengali speaking city outside Bengal region. These ethno-linguistic groups are being assimilated in the Urdu-speaking community Muhajirs. In 2011, an estimated 2.5 million foreign migrants lived in the city, mostly from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Myanmar, and Sri Lanka.

Picture gallery

-

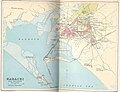

A map of Karachi from 1889

-

The Empress Market, 1890

-

A map of Karachi from 1893

-

View of the dense old native town by the end of the 19th century

-

View of the Bunder Road (now M. A. Jinnah Rd.), 1900

-

Bunder Road

-

Farewell arch erected by the Karachi Port for the Royal visit ofKing George V, 1906

-

British family at Elphinstone St., 1914

See also

- Demographic history of Karachi

- Abdullah Shah Ghazi

- Bhambore

- Culture of Karachi

- Debal

- Demographics of Karachi

- Economy of Karachi

- Education in Karachi

- History of Pakistan

- History of Sindh

- Karachi

- Kolachi jo Goth

- Kolachi

- Krokola

- Kulachi (tribe)

- Mai Kolachi

- Morontobara

- Muhammad bin Qasim

- Politics of Karachi

- Timeline of Karachi history

- Timeline of Karachi

References

- ^ Infiltration by the gods

- ^ Reddy, Anjana. "Archaeology of Indo-Gulf Relations in the Early Historic Period: The Ceramic Evidence". In H.P Ray (ed.). Bridging the Gulf: Maritime Cultural Heritage of the Western Indian Ocean. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers.

- JSTOR 26609161.

- ^ Nicholas F. Gier. FROM MONGOLS TO MUGHALS: RELIGIOUS VIOLENCE IN INDIA 9TH-18TH CENTURIES. Presented at the Pacific Northwest Regional Meeting American Academy of Religion, Gonzaga University, May 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-11.

- ISBN 978-81-7835-792-8.

- ^ P. 151 Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World By André Wink

- ^ P. 164 Notes on the religious, moral, and political state of India before the Mahomedan invasion, chiefly founded on the travels of the Chinese Buddhist priest Fai Han in India, A.D. 399, and on the commentaries of Messrs. Remusat, Klaproth, Burnouf, and Landresse, Lieutenant-Colonel W. H. Sykes by Sykes, Colonel;

- ^ P. 505 The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians by Henry Miers Elliot, John Dowson

- ^ The case of Karachi, Pakistan

- ^ "DAWN – Features; August 8, 2002". Dawn.Com. 8 August 2002. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ^ Kurrachee: (Karachi) Past, Present and Future

- ^ A gazetteer of the province of Sindh

- ISBN 978-1443877442.

- ^ The Dutch East India Company (VOC) and Diewel-Sind (Pakistan) in the 17th and 18th centuries, Floor, W. Institute of Central & West Asian Studies, University of Karachi, 1993–1994, p. 49.

- ^ "The Dutch East India Company's shipping between the Netherlands and Asia 1595–1795". 2 February 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-14.

- ISBN 978-0-19-935444-3.

- JSTOR 1796823.

- ^ Fieldman, Herbert (1960). Karachi through a hundred years. UK: Oxford University Press.

- The North Western Advocate and the Emu Bay Times. Vol. 1, no. 61. Tasmania, Australia. 29 May 1899. p. 2. Retrieved 2018-03-07 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "Port Qasim | About Karachi". Port Qasim Authority. Retrieved 2014-02-10.

- ^ A story behind every name

External links

- A story behind every name

- History of Karachi with old & new Pictures

- 'Traitor of Sindh' Seth Naomal: A case of blasphemy in 1832

- The real Father of Karachi (it's not who you think)

- The real Father of Karachi — II

- Of streets and names

- Harchand Rai Vishan Das: Karachi's beheaded benefactor

- Karachi's Polo Ground: Digging into history

- Ranchor Line: 14 acres of an abandoned identity

- Mr. Strachan and Maulana Wafaai

- The Clifton of yore

- Karachi's Ranchor Line: Where red chilli is no more