Umayyad Caliphate

Umayyad Caliphate ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة ( Umar II, c. 720 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status | Empire | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | Caliph | | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 661–680 | Mu'awiya I (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 744–750 | Marwan II (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Hasan–Muawiya treaty | 661 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 750 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 720[1] | 11,100,000 km2 (4,300,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Caliphate خِلافة |

|---|

|

|

|

| Historical Arab states and dynasties |

|---|

|

The Umayyad Caliphate or Umayyad Empire (

The Umayyads continued the

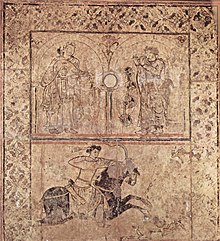

The Umayyad Caliphate ruled over a vast multiethnic and multicultural population. Christians, who still constituted a majority of the caliphate's population, and Jews were allowed to practice their own religion but had to pay the jizya (poll tax) from which Muslims were exempt.[8] Muslims were required to pay the zakat, which was earmarked explicitly for various welfare programmes[8][9] for the benefit of Muslims or Muslim converts.[10] Under the early Umayyad caliphs, prominent positions were held by Christians, some of whom belonged to families that had served the Byzantines. The employment of Christians was part of a broader policy of religious accommodation that was necessitated by the presence of large Christian populations in the conquered provinces, as in Syria. This policy also boosted Mu'awiya's popularity and solidified Syria as his power base.[11][12] The Umayyad era is often considered the formative period in Islamic art.[13]

History

Origins

Early influence

During the pre-Islamic period, the Umayyads or Banu Umayya were a leading clan of the Quraysh tribe of Mecca.[14] By the end of the 6th century, the Umayyads dominated the Quraysh's increasingly prosperous trade networks with Syria and developed economic and military alliances with the nomadic Arab tribes that controlled the northern and central Arabian desert expanses, affording the clan a degree of political power in the region.[15] The Umayyads under the leadership of Abu Sufyan ibn Harb were the principal leaders of Meccan opposition to the Islamic prophet Muhammad, but after the latter captured Mecca in 630, Abu Sufyan and the Quraysh embraced Islam.[16][17] To reconcile his influential Qurayshite tribesmen, Muhammad gave his former opponents, including Abu Sufyan, a stake in the new order.[18][19][20] Abu Sufyan and the Umayyads relocated to Medina, Islam's political centre, to maintain their new-found political influence in the nascent Muslim community.[21]

Muhammad's death in 632 left open the succession of leadership of the Muslim community.

Abu Bakr's successor

Caliphate of Uthman

Umar's successor,

Uthman's nepotism provoked the ire of the Ansar and the members of the shura.[31][32] In 645/46, he added the Jazira (Upper Mesopotamia) to Mu'awiya's Syrian governorship and granted the latter's request to take possession of all Byzantine crown lands in Syria to help pay his troops.[35] He had the surplus taxes from the wealthy provinces of Kufa and Egypt forwarded to the treasury in Medina, which he used at his personal disposal, frequently disbursing its funds and war booty to his Umayyad relatives.[36] Moreover, the lucrative Sasanian crown lands of Iraq, which Umar had designated as communal property for the benefit of the Arab garrison towns of Kufa and Basra, were turned into caliphal crown lands to be used at Uthman's discretion.[37] Mounting resentment against Uthman's rule in Iraq and Egypt and among the Ansar and Quraysh of Medina culminated in the killing of the caliph in 656. In the assessment of the historian Hugh N. Kennedy, Uthman was killed because of his determination to centralize control over the caliphate's government by the traditional elite of the Quraysh, particularly his Umayyad clan, which he believed possessed the "experience and ability" to govern, at the expense of the interests, rights and privileges of many early Muslims.[34]

First Fitna

After Uthman's assassination, Ali was recognized as caliph in Medina, though his support stemmed from the Ansar and the Iraqis, while the bulk of the Quraysh was wary of his rule.

Although Ali was able to replace Uthman's governors in Egypt and Iraq with relative ease, Mu'awiya had developed a solid power-base and an effective military against the Byzantines from the Arab tribes of Syria.[41] Mu'awiya did not claim the caliphate but was determined to retain control of Syria and opposed Ali in the name of avenging his kinsman Uthman, accusing the caliph of culpability in his death.[43][44][45] Ali and Mu'awiya fought to a stalemate at the Battle of Siffin in early 657. Ali agreed to settle the matter with Mu'awiya by arbitration, though the talks failed to achieve a resolution.[46] The decision to arbitrate fundamentally weakened Ali's political position as he was forced to negotiate with Mu'awiya on equal terms, while it drove a significant number of his supporters, who became known as the Kharijites, to revolt.[47] Ali's coalition steadily disintegrated and many Iraqi tribal nobles secretly defected to Mu'awiya, while the latter's ally Amr ibn al-As ousted Ali's governor from Egypt in July 658.[46][48] In July 660 Mu'awiya was formally recognized as caliph in Jerusalem by his Syrian tribal allies.[46] Ali was assassinated by a Kharijite dissident in January 661.[49] His son Hasan succeeded him but abdicated in return for compensation upon Mu'awiya's arrival to Iraq with his Syrian army in the summer.[46] At that point, Mu'awiya entered Kufa and received the allegiance of the Iraqis.[50]

Sufyanid period

Caliphate of Mu'awiya

The recognition of Mu'awiya in Kufa, referred to as the "year of unification of the community" in the Muslim traditional sources, is generally considered the start of his caliphate.

Mu'awiya's main challenge was reestablishing the unity of the Muslim community and asserting his authority and that of the caliphate in the provinces amid the political and social disintegration of the First Fitna.

Succession of Yazid I and collapse of Sufyanid rule

In contrast to Uthman, Mu'awiya restricted the influence of his Umayyad kinsmen to the governorship of Medina, where the dispossessed Islamic elite, including the Umayyads, was suspicious or hostile toward his rule.[60][67] However, in an unprecedented move in Islamic politics, Mu'awiya nominated his own son, Yazid I, as his successor in 676, introducing hereditary rule to caliphal succession and, in practice, turning the office of the caliph into a kingship.[68] The act was met with disapproval or opposition by the Iraqis and the Hejaz-based Quraysh, including the Umayyads, but most were bribed or coerced into acceptance.[69] Yazid acceded after Mu'awiya's death in 680 and almost immediately faced a challenge to his rule by the Kufan partisans of Ali who had invited Ali's son and Muhammad's grandson Husayn to stage a revolt against Umayyad rule from Iraq.[70] An army mobilized by Iraq's governor Ibn Ziyad intercepted and killed Husayn outside Kufa at the Battle of Karbala. Although it stymied active opposition to Yazid in Iraq, the killing of Muhammad's grandson left many Muslims outraged and significantly increased Kufan hostility toward the Umayyads and sympathy for the family of Ali.[71]

The next major challenge to Yazid's rule emanated from the Hejaz where

Early Marwanid period

Marwanid transition and end of Second Fitna

Umayyad authority nearly collapsed in their Syrian stronghold after the death of Mu'awiya II.

In 685, Marwan and Ibn Bahdal expelled the

Domestic consolidation and centralization

Iraq remained politically unstable and the garrisons of Kufa and Basra had become exhausted by warfare with Kharijite rebels.[95][84] In 694 Abd al-Malik combined both cities as a single province under the governorship of al-Hajjaj, who oversaw the suppression of the Kharijite revolts in Iraq and Iran by 698 and was subsequently given authority over the rest of the eastern caliphate.[96][97] Resentment among the Iraqi troops towards al-Hajjaj's methods of governance, particularly his death threats to force participation in the war efforts and his reductions to their stipends, culminated with a mass Iraqi rebellion against the Umayyads in c. 700. The leader of the rebels was the Kufan nobleman Ibn al-Ash'ath, grandson of al-Ash'ath ibn Qays.[98] Al-Hajjaj defeated Ibn al-Ash'ath's rebels at the Battle of Dayr al-Jamajim in April.[99][100] The suppression of the revolt marked the end of the Iraqi muqātila as a military force and the beginning of Syrian military domination of Iraq.[101][100] Iraqi internal divisions, and the utilization of more disciplined Syrian forces by Abd al-Malik and al-Hajjaj, voided the Iraqis' attempt to reassert power in the province.[99]

To consolidate Umayyad rule after the Second Fitna, the Marwanids launched a series of centralization,

In 693, the Byzantine gold solidus was replaced in Syria and Egypt with the dinar.[101][105] Initially, the new coinage contained depictions of the caliph as the spiritual leader of the Muslim community and its supreme military commander.[106] This image proved no less acceptable to Muslim officialdom and was replaced in 696 or 697 with image-less coinage inscribed with Qur'anic quotes and other Muslim religious formulas.[105] In 698/99, similar changes were made to the silver dirhams issued by the Muslims in the former Sasanian Persian lands of the eastern caliphate.[107] Arabic replaced Persian as the language of the dīwān in Iraq in 697, Greek in the Syrian dīwān in 700, and Greek and Coptic in the Egyptian dīwān in 705/06.[105][108][109] Arabic ultimately became the sole official language of the Umayyad state,[107] but the transition in faraway provinces, such as Khurasan, did not occur until the 740s.[110] Although the official language was changed, Greek and Persian-speaking bureaucrats who were versed in Arabic kept their posts.[111] According to Gibb, the decrees were the "first step towards the reorganization and unification of the diverse tax-systems in the provinces, and also a step towards a more definitely Muslim administration".[101] Indeed, it formed an important part of the Islamization measures that lent the Umayyad Caliphate "a more ideological and programmatic coloring it had previously lacked", according to Blankinship.[112]

In 691/92, Abd al-Malik completed the

Renewal of conquests

Muslim state at the death of Muhammad Expansion under the Rashidun Caliphate Expansion under the Umayyad Caliphate

Under al-Walid I the Umayyad Caliphate reached its greatest territorial extent.

لهند

لهندAl-Hajjaj managed the eastern expansion from Iraq.

Al-Walid I's successor, his brother

On the Byzantine front, Sulayman took up his predecessor's project to capture Constantinople with increased vigor.

Caliphate of Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz

Contrary to expectations of a son or brother succeeding him, Sulayman had nominated his cousin, Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz, as his successor and he took office in 717. After the Arabs' severe losses in the offensive against Constantinople, Umar drew down Arab forces on the caliphate's war fronts, though Narbonne in modern France was conquered during his reign.[150][146][151] To maintain stronger oversight in the provinces, Umar dismissed all his predecessors' governors, his new appointees being generally competent men he could control. To that end, the massive viceroyalty of Iraq and the east was broken up.[150][152]

Umar's most significant policy entailed fiscal reforms to equalize the status of the Arabs and mawali,[153] thus remedying a long-standing issue which threatened the Muslim community.[154] The jizya (poll tax) on the mawali was eliminated.[155] Hitherto, the jizya, which was traditionally reserved for the non-Muslim majorities of the caliphate, continued to be imposed on non-Arab converts to Islam, while all Muslims who cultivated conquered lands were liable to pay the kharaj (land tax). Since avoidance of taxation incentivized both mass conversions to Islam and abandonment of land for migration to the garrison cities, it put a strain on tax revenues, especially in Egypt, Iraq and Khurasan.[156] Thus, "the Umayyad rulers had a vested interest in preventing the conquered peoples from accepting Islam or forcing them to continue paying those taxes from which they claimed exemption as Muslims", according to Hawting.[157] To prevent a collapse in revenue, the converts' lands would become the property of their villages and remain liable for the full rate of the kharaj.[154]

In tandem, Umar intensified the Islamization drive of his Marwanid predecessors, enacting measures to distinguish Muslims from non-Muslims and inaugurating Islamic iconoclasm.[158] His position among the Umayyad caliphs is unusual, in that he became the only one to have been recognized in subsequent Islamic tradition as a genuine caliph (khalifa) and not merely as a worldly king (malik).[159]

Late Marwanid period

After the death of Umar II, another son of Abd al-Malik,

Yazid II reversed Umar II's equalization reforms, reimposing the jizya on the mawali, which sparked revolts in Khurasan in 721 or 722 that persisted for some twenty years and met strong resistance among the Berbers of Ifriqiya, where the Umayyad governor was assassinated by his discontented Berber guards.

Caliphate of Hisham and end of expansion

The final son of Abd al-Malik to become caliph was Hisham (r. 724–743), whose long and eventful reign was above all marked by the curtailment of military expansion. Hisham established his court at Resafa in northern Syria, which was closer to the Byzantine border than Damascus, and resumed hostilities against the Byzantines, which had lapsed following the failure of the last siege of Constantinople. The new campaigns resulted in a number of successful raids into Anatolia, but also in a major defeat (the Battle of Akroinon), and did not lead to any significant territorial expansion.

From the caliphate's north-western African bases, a series of raids on coastal areas of the

In the

Hisham suffered still worse defeats in the east, where his armies attempted to subdue both

Discontent among the Khorasani Arabs rose sharply after the losses suffered in the Battle of the Defile in 731. In 734, al-Harith ibn Surayj led a revolt that received broad backing from Arabs and natives alike, capturing Balkh but failing to take Merv. After this defeat, al-Harith's movement seems to have been dissolved. The problem of the rights of non-Arab Muslims would continue to plague the Umayyads.

Third Fitna

Hisham was succeeded by

In 744, Yazid III, a son of al-Walid I, was proclaimed caliph in Damascus, and his army tracked down and killed al-Walid II. Yazid III has received a certain reputation for piety and may have been sympathetic to the Qadariyya. He died a mere six months into his reign.

Yazid had appointed his brother,

Marwan also faced significant opposition from Kharijites in Iraq and Iran, who put forth first Dahhak ibn Qays and then Abu Dulaf as rival caliphs. In 747, Marwan managed to reestablish control of Iraq, but by this time a more serious threat had arisen in Khorasan.

Abbasid Revolution and fall

The

Beginning around 719, Hashimiyya missions began to seek adherents in Khurasan. Their campaign was framed as one of proselytism (

Around 746,

The victors desecrated the tombs of the Umayyads in Syria, sparing only that of

Some Umayyads also survived in Syria,[168] and their descendants would once more attempt to restore their old regime during the Fourth Fitna. Two Umayyads, Abu al-Umaytir al-Sufyani and Maslama ibn Ya'qub, successively seized control of Damascus from 811 to 813, and declared themselves caliphs. However, their rebellions were suppressed.[169]

Previté-Orton argues that the reason for the decline of the Umayyads was the rapid expansion of Islam. During the Umayyad period, mass conversions brought Persians, Berbers, Copts, and Aramaic to Islam. These mawalis (clients) were often better educated and more civilised than their Arab overlords. The new converts, on the basis of equality of all Muslims, transformed the political landscape. Previté-Orton also argues that the feud between Syria and Iraq further weakened the empire.[170]

Administration

The first four caliphs created a stable administration for the empire, following the practices and administrative institutions of the Byzantine Empire which had ruled the same region previously.[171] These consisted of four main governmental branches: political affairs, military affairs, tax collection, and religious administration. Each of these was further subdivided into more branches, offices, and departments.

Provinces

Geographically, the empire was divided into several provinces, the borders of which changed numerous times during the Umayyad reign. Each province had a governor appointed by the caliph. The governor was in charge of the religious officials, army leaders, police, and civil administrators in his province. Local expenses were paid for by taxes coming from that province, with the remainder each year being sent to the central government in Damascus. As the central power of the Umayyad rulers waned in the later years of the dynasty, some governors neglected to send the extra tax revenue to Damascus and created great personal fortunes.[172]

Government workers

As the empire grew, the number of qualified Arab workers was too small to keep up with the rapid expansion of the empire. Therefore, Muawiya allowed many of the local government workers in conquered provinces to keep their jobs under the new Umayyad government. Thus, much of the local government's work was recorded in Greek, Coptic, and Persian. It was only during the reign of Abd al-Malik that government work began to be regularly recorded in Arabic.[172]

Military

The Umayyad army was mainly Arab, with its core consisting of those who had settled in urban Syria and the Arab tribes who originally served in the army of the Eastern Roman Empire in Syria. These were supported by tribes in the Syrian desert and in the frontier with the Byzantines, as well as Christian Syrian tribes. Soldiers were registered with the Army Ministry, the Diwan Al-Jaysh, and were salaried. The army was divided into junds based on regional fortified cities.[173] The Umayyad Syrian forces specialised in close order infantry warfare, and favoured using a kneeling spear wall formation in battle, probably as a result of their encounters with Roman armies. This was radically different from the original Bedouin style of mobile and individualistic fighting.[174][175]

Coinage

The Byzantine and Sassanid Empires relied on money economies before the Muslim conquest and that system remained in effect during the Umayyad period. Byzantine coinage was used until 658; Byzantine gold coins were still in use until the monetary reforms c. 700.[176] In addition to this, the Umayyad government began to mint its own coins in Damascus, which were initially similar to pre-existing coins but evolved in an independent direction. These were the first coins minted by a Muslim government in history.[172]

Early Islamic coins re-used Byzantine and Sasanian iconography directly but added new Islamic elements.[177] So-called "Arab-Byzantine" coins replicated Byzantine coins and were minted in Levantine cities before and after the Umayyads rose to power.[178] Some examples of these coins, likely minted in Damascus, copied the coins of Byzantine emperor Heraclius, including a depiction of the emperor and his son Heraclius Constantine. On the reverse side, the traditional Byzantine cross-on-steps image was modified to avoid any explicitly non-Islamic connotation.[177]

In the 690s, under Abd al-Malik's reign, a new period of experimentations began.

Between 696 and 699, the caliph introduced a new system of coinage of gold, silver, and bronze.

One group of bronze coins from Palestine,

Central diwans

To assist the caliph in administration there were six boards at the centre: Diwan al-Kharaj (the Board of Revenue), Diwan al-Rasa'il (the Board of Correspondence), Diwan al-Khatam (the Board of Signet), Diwan al-Barid (the Board of Posts), Diwan al-Qudat (the Board of Justice) and Diwan al-Jund (the Military Board)

Diwan al-Kharaj

The Central Board of Revenue administered the entire finances of the empire. It also imposed and collected taxes and disbursed revenue.

Diwan al-Rasa'il

A regular Board of Correspondence was established under the Umayyads. It issued state missives and circulars to the Central and Provincial Officers. It coordinated the work of all Boards and dealt with all correspondence as the chief secretariat.

Diwan al-Khatam

In order to reduce forgery, Diwan al-Khatam (Bureau of Registry), a kind of state chancellery, was instituted by Mu'awiyah. It used to make and preserve a copy of each official document before sealing and despatching the original to its destination. Thus in the course of time a state archive developed in Damascus by the Umayyads under Abd al-Malik. This department survived till the middle of the Abbasid period.

Diwan al-Barid

Mu'awiyah introduced the postal service, Abd al-Malik extended it throughout his empire, and Walid made full use of it. Umar bin Abdul-Aziz developed it further by building caravanserais at stages along the Khurasan highway. Relays of horses were used for the conveyance of dispatches between the caliph and his agents and officials posted in the provinces. The main highways were divided into stages of 12 miles (19 km) each and each stage had horses, donkeys, or camels ready to carry the post. Primarily the service met the needs of Government officials, but travellers and their important dispatches were also benefited by the system. The postal carriages were also used for the swift transport of troops. They were able to carry fifty to a hundred men at a time. Under Governor Yusuf bin Umar, the postal department of Iraq costs 4,000,000 dirhams a year.

Diwan al-Qudat

In the early period of Islam, justice was administered by Muhammad and the orthodox caliphs in person. After the expansion of the Islamic State, Umar al-Faruq had to separate the judiciary from the general administration and appointed the first qadi in Egypt as early as AD 643/23 AH. After 661, a series of judges served in Egypt during the caliphates of Hisham and Walid II.

Diwan al-Jund

The Diwan of Umar, assigning annuities to all Arabs and to the Muslim soldiers of other races, underwent a change in the hands of the Umayyads. The Umayyads meddled with the register and the recipients regarded pensions as the subsistence allowance even without being in active service. Hisham reformed it and paid only to those who participated in the battle. On the pattern of the Byzantine system, the Umayyads reformed their army organization in general and divided it into five corps: the centre, two wings, vanguards, and rearguards, following the same formation while on the march or on a battlefield. Marwan II (740–50) abandoned the old division and introduced the Kurdus (cohort), a small compact body. The Umayyad troops were divided into three divisions: infantry, cavalry, and artillery. Arab troops were dressed and armed in Greek fashion. The Umayyad cavalry used plain and round saddles. The artillery used the arradah (ballista), the manjaniq (mangonel), and the dabbabah or kabsh (battering ram). The heavy engines, siege machines, and baggage were carried on camels behind the army.

Social organization

The Umayyad Caliphate had four main social classes:

- Muslim Arabs

- Muslim non-Arabs (clients of the Muslim Arabs)

- Dhimmis (non-Muslim free persons such as Christians, Jews and Zoroastrians)

- Slaves

The Muslim Arabs were at the top of the society and saw it as their duty to rule over the conquered areas. The Arab Muslims held themselves in higher esteem than Muslim non-Arabs and generally did not mix with other Muslims.

As Islam spread, more and more of the Muslim population consisted of non-Arabs. This caused social unrest, as the new converts were not given the same rights as Muslim Arabs. Also, as conversions increased, tax revenues (peasant tax) from non-Muslims decreased to dangerous lows. These issues continued to worsen until they helped cause the

Non-Muslims

Non-Muslim groups in the Umayyad Caliphate, which included Christians, Jews, Zoroastrians, and

Although the Umayyads were harsh when it came to defeating their Zoroastrian adversaries,

Although non-Muslims could not hold the highest public offices in the empire, they held many bureaucratic positions within the government. An important example of Christian employment in the Umayyad government is that of

Muawiya's marriage to

Tom Holland writes that Christians, Jews,

Architecture

The Umayyads constructed grand

Under Umayyad patronage, Islamic architecture was derived from established Byzantine and Sasanian architectural traditions, but it also innovated by combining elements of these styles together, experimenting with new building types, and implementing lavish decorative programs.[195] Byzantine-style mosaics are prominently featured in both the Dome of the Rock and the Great Mosque of Damascus, but the lack of human figures in their imagery was a new trait that demonstrates an Islamic taboo on figural representation in religious art. Palaces were decorated with floor mosaics, frescoes, and relief carving, and some of these included representations of human figures and animals.[195] Umayyad architecture was thus an important transitional period during which early Islamic architecture and visual culture began to develop its own distinct identity.[198]

The later offshoot of the Umayyad dynasty in

Legacy

| History of the Levant |

|---|

| Prehistory |

| Ancient history |

|

| Classical antiquity |

|

| Middle Ages |

| Modern history |

The Umayyad caliphate was marked both by territorial expansion and by the administrative and cultural problems that such expansion created. Despite some notable exceptions, the Umayyads tended to favor the rights of the old Arab families, and in particular their own, over those of newly converted Muslims (mawali). Therefore, they held to a less universalist conception of Islam than did many of their rivals. As G.R. Hawting has written, "Islam was in fact regarded as the property of the conquering aristocracy."[200]

During the period of the Umayyads, Arabic became the administrative language and the process of Arabization was initiated in the Levant, Mesopotamia, North Africa, and Iberia.[201] State documents and currency were issued in Arabic. Mass conversions also created a growing population of Muslims in the territory of the caliphate.

According to one common view, the Umayyads transformed the caliphate from a religious institution (during the Rashidun caliphate) to a dynastic one.[196] However, the Umayyad caliphs do seem to have understood themselves as the representatives of God on earth, and to have been responsible for the "definition and elaboration of God's ordinances, or in other words the definition or elaboration of Islamic law."[202]

The Umayyads have met with a largely negative reception from later Islamic historians, who have accused them of promoting a kingship (mulk, a term with connotations of tyranny) instead of a true caliphate (khilafa). In this respect it is notable that the Umayyad caliphs referred to themselves not as khalifat rasul Allah ("successor of the messenger of God", the title preferred by the tradition), but rather as khalifat Allah ("deputy of God"). The distinction seems to indicate that the Umayyads "regarded themselves as God's representatives at the head of the community and saw no need to share their religious power with, or delegate it to, the emergent class of religious scholars."

The book Al Muwatta, by Imam Malik, was written in the early Abbasid period in Medina. It does not contain any anti-Umayyad content because it was more concerned with what the Quran and what Muhammad said and was not a history book on the Umayyads.[

Modern Arab nationalism regards the period of the Umayyads as part of the Arab Golden Age which it sought to emulate and restore.[dubious ] This is particularly true of Syrian nationalists and the present-day state of Syria, centered like that of the Umayyads on Damascus.[207] The Umayyad banners were white, after the banner of Muawiya ibn Abi Sufyan;[208] it is now one of the four Pan-Arab colours which appear in various combinations on the flags of most Arab countries.

Religious perspectives

Sunni

Many Muslims criticized the Umayyads for having too many non-Muslim, former Roman administrators in their government, e.g., St. John of Damascus.[209] As the Muslims took over cities, they left the people's political representatives, the Roman tax collectors, and the administrators in the office. The taxes to the central government were calculated and negotiated by the people's political representatives. Both the central and local governments were compensated for the services each provided. Many Christian cities used some of the taxes to maintain their churches and run their own organizations. Later, the Umayyads were criticized by some Muslims for not reducing the taxes of the people who converted to Islam.[210]

Later, when

The only Umayyad ruler who is unanimously praised by Sunni sources for his devout piety and justice is Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz.[

Shi'a

The negative view of the Umayyads held by

Bahá'í

Asked for an explanation of the prophecies in the

The seven heads of the dragon are symbolic of the seven provinces of the lands dominated by the Umayyads: Damascus, Persia, Arabia, Egypt, Africa, Andalusia, and Transoxiana. The ten horns represent the ten names of the leaders of the Umayyad dynasty: Abu Sufyan, Muawiya, Yazid, Marwan, Abd al-Malik, Walid, Sulayman, Umar, Hisham, and Ibrahim. Some names were re-used, as in the case of Yazid II and Yazid III, which were not accounted for in this interpretation.

List of caliphs

| Caliph | Reign |

|---|---|

| Caliphs of Damascus | |

Muawiya I ibn Abu Sufyan |

28 July 661 – 27 April 680 |

| Yazid I ibn Muawiyah | 27 April 680 – 11 November 683 |

Muawiya II ibn Yazid |

11 November 683 – June 684 |

| Marwan I ibn al-Hakam | June 684 – 12 April 685 |

| Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan | 12 April 685 – 8 October 705 |

| al-Walid I ibn Abd al-Malik | 8 October 705 – 23 February 715 |

| Sulayman ibn Abd al-Malik | 23 February 715 – 22 September 717 |

| Umar ibn Abd al-Aziz | 22 September 717 – 4 February 720 |

| Yazid II ibn Abd al-Malik | 4 February 720 – 26 January 724 |

| Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik | 26 January 724 – 6 February 743 |

| al-Walid II ibn Yazid | 6 February 743 – 17 April 744 |

| Yazid III ibn al-Walid | 17 April 744 – 4 October 744 |

| Ibrahim ibn al-Walid | 4 October 744 – 4 December 744 |

Jazira ) |

4 December 744 – 25 January 750 |

See also

Notes

- al-Walid ibn Utba, the son of Mu'awiya I's full brother, died shortly after Mu'awiya II's death, while another paternal uncle of the deceased caliph, Uthman ibn Anbasa ibn Abi Sufyan, who had support from the Kalb of the Jordan district, recognized the caliphate of his maternal uncle Ibn al-Zubayr.[75] Ibn Bahdal favored Mu'awiya II's brothers, Khalid and Abd Allah, for the succession, but they were viewed as too young and inexperienced by most of the pro-Umayyad tribal nobility in Syria.[78][79]

- al-Ya'qubi, the first Muslim caliph to employ Christians in administrative positions.[188]

References

- ^ from the original on 19 November 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ "Umayyad". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ "Umayyad". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 12 May 2019. • "Umayyad". Oxford Dictionaries US Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 12 May 2019. • "Umayyad". Oxford Dictionaries UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. • "Umayyad". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ "Umayyad dynasty". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- ^ Bukhari, Sahih. "Sahih Bukhari: Read, Study, Search Online". Archived from the original on 4 February 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2013.

- ]

- ^ Venable, Francis Preston (1894). A Short History of Chemistry. Heath. p. 21.

- ^ a b Rahman 1999, p. 128.

- ^ "Islamic Economics". www.hetwebsite.net. Archived from the original on 5 November 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2018.

- ^ Benthal, Jonathan (1998). "The Qur'an's Call to Alms Zakat, the Muslim Tradition of Alms-giving" (PDF). ISIM Newsletter. 98 (1): 13–12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-7614-7571-2. Archivedfrom the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-84765-854-8. Archivedfrom the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ Yalman, Suzan (October 2001). "The Art of the Umayyad Period (661–750)". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. Based on original work by Linda Komaroff. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on 20 September 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ Levi Della Vida & Bosworth 2000, p. 838.

- ^ Donner 1981, p. 51.

- ^ Hawting 2000, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Hawting 2000, p. 23.

- ^ Donner 1981, p. 77.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 20.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 50.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 51.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 51–53.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 45.

- ^ Donner 1981, p. 114.

- ^ a b Madelung 1997, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b Madelung 1997, p. 61.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 62–64.

- ^ a b c d e Madelung 1997, p. 80.

- ^ a b c d Wellhausen 1927, p. 45.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 70.

- ^ a b c Kennedy 2004, p. 75.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 63.

- ^ Madelung 1997, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 81.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 141.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Hawting 2000, p. 27.

- ^ a b c Kennedy 2004, p. 76.

- ^ a b Wellhausen 1927, p. 53.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 76, 78.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Madelung 1997, p. 190.

- ^ a b c d e f Hinds 1993, p. 265.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 79.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 80.

- ^ Hinds 1993, p. 59.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 59.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 59–60.

- ^ Hawting 2000a, p. 842.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 55.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 86–87.

- ^ Kaegi 1992, p. 247.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Lilie 1976, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 82.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b c d Kennedy 2004, p. 83.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 83–85.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 85.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2004, p. 86.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 87.

- ^ Kennedy 2007, p. 209.

- ^ Christides 2000, p. 790.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 135.

- ^ Duri 2011, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 88.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 88–89.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2004, p. 89.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 89–90.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2004, p. 90.

- ^ Gibb 1960a, p. 55.

- ^ a b Bosworth 1993, p. 268.

- ^ Duri 2011, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Levi Della Vida & Bosworth 2000, pp. 838–839.

- ^ a b c Kennedy 2004, p. 91.

- ^ Duri 2011, pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2004, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Crone 1994, p. 45.

- ^ a b Crone 1994, p. 46.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 201–202.

- ^ a b c d Kennedy 2001, p. 33.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 182.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 92.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 93.

- ^ Kennedy 2001, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Dixon 1969, pp. 220–222.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Dixon 1969, pp. 174–176, 206–208.

- ^ Dixon 1969, pp. 235–239.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 98.

- ^ Gibb 1960b, p. 76.

- ^ Kennedy 2016, p. 87.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 231.

- ^ Kennedy 2016, pp. 87–88.

- ^ a b c d Kennedy 2016, p. 88.

- ^ a b c d Kennedy 2001, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Gibb 1960b, p. 77.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2016, p. 85.

- ^ Hawting 2000, p. 62.

- ^ a b c Kennedy 2016, p. 89.

- ^ a b c Blankinship 1994, pp. 28, 94.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, p. 28.

- ^ a b Blankinship 1994, p. 94.

- ^ Hawting 2000, p. 63.

- ^ Duri 1965, p. 324.

- ^ Hawting 2000, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 219–220.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, p. 95.

- ^ Johns 2003, pp. 424–426.

- ^ Elad 1999, p. 45.

- ^ a b Grabar 1986, p. 299.

- ^ a b Hawting 2000, p. 60.

- ^ Johns 2003, pp. 425–426.

- ^ Elisséeff 1965, p. 801.

- ^ Hillenbrand 1994, pp. 71–72.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2016, p. 90.

- ^ Lilie 1976, pp. 110–112.

- ^ Lilie 1976, pp. 112–116.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, p. 107.

- ^ Ter-Ghewondyan 1976, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Lilie 1976, pp. 113–115.

- ^ a b Kaegi 2010, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Talbi 1971, p. 271.

- ^ Kennedy 2007, p. 217.

- ^ Lévi-Provençal 1993, p. 643.

- ^ Kaegi 2010, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Kennedy 2002, p. 127.

- ^ a b Wellhausen 1927, p. 438.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 437–438.

- ^ Kennedy 2016, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Dietrich 1971, p. 41.

- ^ Kennedy 2016, p. 91.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, p. 82.

- ^ a b Eisener 1997, p. 821.

- ^ Gibb 1923, p. 54.

- ^ Beckwith 1993, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Madelung 1975, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Madelung 1993.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, p. 344.

- ^ Powers 1989, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, pp. 347–348.

- ^ a b Blankinship 1994, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Lilie 1976, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, pp. 117–121.

- ^ Lilie 1976, pp. 143–144, 158–162.

- ^ a b Cobb 2000, p. 821.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, p. 268–269.

- ^ Kennedy 2004, p. 106.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, p. 31.

- ^ a b Kennedy 2004, p. 107.

- ^ Hawting 2000, p. 77.

- ^ Hawting 2000, pp. 77–79.

- ^ Hawting 2000, p. 78.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, p. 32.

- ^ Kennedy 2002, p. 107.

- ^ Wellhausen 1927, pp. 313–318.

- ^ Lammens & Blankinship 2002, p. 311.

- ^ Blankinship 1994, p. 87.

- ISBN 978-0-8478-0081-0.

- ^ Allan, J.; Haig, T. Wolseley; Dodwell, H. H. (1934). "Northern India in Medieval Times". In Dodwell, H. H. (ed.). The Cambridge Shorter History of India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 131–132.

- ISBN 978-0520242258.

- ISBN 9781563243349.

- ^ Cobb 2001, pp. 47–50.

- ^ Cobb 2001, p. 43.

- ^ Cobb 2001, pp. 56–61.

- ^ Previté-Orton 1971, vol. 1, p. 239.

- ^ Robinson, Neal (1999). Islam: A Concise Introduction. RoutledgeCurzon. p. 22.

- ^ a b c Ochsenwald 2004, p. 57.

- ISBN 978-1-84603-890-7.

- ISBN 978-1-84884-612-8.

- ^ Kennedy 2007a.

- ^ Sanchez 2015, p. 324.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-300-21111-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-57506-547-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4744-6045-3.

- ^ a b Flood 2001, p. 89 (see footnote 146).

- JSTOR 506971.

- ^ Ochsenwald 2004, p. 55–56.

- ^ S2CID 201748179.

- ^ Recorded by Ibn Abu Shayba in Al-Musanaf and Abu 'Ubaid Ibn Sallam in his book Al-Amwal, pp.123

- ^ a b Donner, Fred M. (May 2010). Muhammad and the Believers: At the Origins of Islam. pp. 110–111.

- ^ Ochsenwald 2004, p. 56.

- ^ a b c "Sarğūn ibn Manṣūr ar-Rūmī". Prosopographie der mittelbyzantinischen Zeit Online (in German). De Gruyter. 2013. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- ^ a b Griffith 2016, p. 31.

- ^ Morony 1987, p. 216.

- ^ Sprengling 1939, p. 213.

- ^ Rahman 1999, p. 72.

- ^ a b Holland 2013, p. 402.

- ^ Holland 2013, p. 406.

- ^ Flood 2001, p. 2.

- ^ ISBN 9781134613663.

- ^ a b Previté-Orton 1971, p. 236.

- ^ Flood 2001, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Flood 2001, pp. 22–24.

- ISBN 0870996371.

- ^ Hawting 2000, p. 4.

- ^ Lapidus 2014, p. 50.

- ^ Crone & Hinds 1986, p. 43.

- ^ Hawting 2000, p. 13.

- ^ Muawiya Restorer of the Muslim Faith By Aisha Bewley Page 41

- ISBN 978-0-521-53934-0. Archivedfrom the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-9742172-0-8. Archivedfrom the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ Gilbert 2013, pp. 21–24, 39–40.

- ^ Hathaway 2012, p. 97.

- ISBN 978-1-4051-5204-4. Archivedfrom the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 22 November 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Student Resources, Chapter 12: The First Global Civilization: The Rise and Spread of Islam, IV. The Arab Empire of the Umayyads, G. Converts and 'People of the Book'". occawlonline.pearsoned.com. Archived from the original on 21 May 2002.

- ^ Umar Ibn Abdul Aziz By Imam Abu Muhammad Abdullah ibn Abdul Hakam died 214 AH 829 C.E. Publisher Zam Zam Publishers Karachi

- ISBN 978-1-4960-4085-5. Archived from the originalon 20 January 2004.

- ^ "Sermon 92: About the annihilation of the Kharijites, the mischief mongering of Umayyads and the vastness of his own knowledge". nahjulbalagha.org. Archived from the original on 19 August 2007.

- ISBN 978-965-223-501-5. Archivedfrom the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 22 November 2020.

- ^ "Bible". biblegateway.com. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-87743-190-9. Archivedfrom the original on 8 December 2010. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

- ISBN 978-0-87743-190-9. Archivedfrom the original on 24 September 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

Bibliography

- ISBN 978-0-7914-1827-7.

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (1993). The Tibetan Empire in Central Asia: A History of the Struggle for Great Power Among Tibetans, Turks, Arabs, and Chinese During the Early Middle Ages. ISBN 978-0-691-02469-1.

- ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Christides, Vassilios (2000). "ʿUkba b. Nāfiʿ". In ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

- Crone, Patricia; Hinds, Martin (1986). God's Caliph: Religious Authority in the First Centuries of Islam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-32185-9.

- Crone, Patricia (1994). "Were the Qays and Yemen of the Umayyad Period Political Parties?". Der Islam. 71 (1). Walter de Gruyter and Co.: 1–57. S2CID 154370527.

- ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

- Cobb, Paul M. (2001). White Banners: Contention in 'Abbasid Syria, 750–880. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0791448809.

- Dietrich, Albert (1971). "Al-Ḥadjdjādj b. Yūsuf". In OCLC 495469525.

- ISBN 978-1-4008-4787-7.

- Duri, Abd al-Aziz (1965). "Dīwān". In OCLC 495469475.

- Duri, Abd al-Aziz (2011). Early Islamic Institutions: Administration and Taxation from the Caliphate to the Umayyads and ʿAbbāsids. Translated by Razia Ali. London and Beirut: I. B. Tauris and Centre for Arab Unity Studies. ISBN 978-1-84885-060-6.

- Dixon, 'Abd al-Ameer (August 1969). The Umayyad Caliphate, 65–86/684–705: (A Political Study) (Thesis). London: University of London, SOAS.

- Eisener, R. (1997). "Sulaymān b. ʿAbd al-Malik". In ISBN 978-90-04-10422-8.

- Elad, Amikam (1999). Medieval Jerusalem and Islamic Worship: Holy Places, Ceremonies, Pilgrimage (2nd ed.). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-10010-5.

- Elisséeff, Nikita (1965). "Dimashk". In OCLC 495469475.

- Flood, Finbarr Barry (2001). The Great Mosque of Damascus: Studies on the Makings of an Umayyad Visual Culture. Boston: Brill. ISBN 90-04-11638-9.

- OCLC 499987512.

- OCLC 495469456.

- OCLC 495469456.

- Gilbert, Victoria J. (May 2013). Syria for the Syrians: the rise of Syrian nationalism, 1970–2013 (PDF) (MA). Northeastern University. . Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ISBN 978-90-04-07819-2.

- Griffith, Sidney H. (2016). "The Manṣūr Family and Saint John of Damascus: Christians and Muslims in Umayyad Times". In Antoine Borrut; Fred M. Donner (eds.). Christians and Others in the Umayyad State. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. pp. 29–51. ISBN 978-1-614910-31-2.

- Hathaway, Jane (2012). A Tale of Two Factions: Myth, Memory, and Identity in Ottoman Egypt and Yemen. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-8610-8.

- ISBN 0-415-24072-7.

- Hawting, G. R. (2000). "Umayyads". In ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

- ISBN 978-0-88706-810-2.

- Hillenbrand, Robert (1994). Islamic Architecture: Form, Function and Meaning. New York: ISBN 0-231-10132-5.

- ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- Holland, Tom (2013). In the Shadow of the Sword The Battle for Global Empire and the End of the Ancient World. Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-12235-9.

- Johns, Jeremy (January 2003). "Archaeology and the History of Early Islam: The First Seventy Years". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 46 (4): 411–436. S2CID 163096950.

- ISBN 0-521-41172-6.

- ISBN 978-0-521-19677-2.

- ISBN 0-415-25093-5.

- Kennedy, Hugh N. (2002). "Al-Walīd (I)". In ISBN 978-90-04-12756-2.

- ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- ISBN 978-0-306-81740-3.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2007a). "1. The Foundations of Conquest". The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In. Hachette, UK. ISBN 978-0-306-81728-1.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2007a). "1. The Foundations of Conquest". The Great Arab Conquests: How the Spread of Islam Changed the World We Live In. Hachette, UK.

- ISBN 978-90-04-12756-2.

- ISBN 978-0-521-51430-9.

- ISBN 978-1-138-78761-2.

- ISBN 978-90-04-11211-7.

- ISBN 978-90-04-09419-2.

- OCLC 797598069.

- ISBN 0-521-20093-8.

- ISBN 978-1-56859-003-5.

- ISBN 0-521-56181-7.

- ISBN 978-0-87395-933-9.

- OCLC 495469525.

- ISBN 978-0-07-244233-5.

- Powers, David S., ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXIV: The Empire in Transition: The Caliphates of Sulaymān, ʿUmar, and Yazīd, A.D. 715–724/A.H. 96–105. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0072-2.

- Previté-Orton, C. W.(1971). The Shorter Cambridge Medieval History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rahman, H.U. (1999). A Chronology Of Islamic History 570–1000 CE.

- Sanchez, Fernando Lopez (2015). "The Mining, Minting, and Acquisition of Gold in the Roman and Post-Roman World". In Paul Erdkamp; Koenraad Verboven; Arjan Zuiderhoek (eds.). Ownership and Exploitation of Land and Natural Resources in the Roman World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780191795831.

- Sprengling, Martin (April 1939). "From Persian to Arabic". The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures. 56 (2). The University of Chicago Press: 175–224. S2CID 170486943.

- OCLC 490638192.

- ISBN 0-8047-2630-2.

- OCLC 752790641.

Further reading

- Al-Ajmi, Abdulhadi (2014). "The Umayyads". In Fitzpatrick, C.; Walker, A. (eds.). Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-177-2.

- Bewley, Aisha Abdurrahman (2002). Muʻawiya: Restorer of the Muslim Faith. Dar Al Taqwa. ISBN 9781870582568.

- Boekhoff-van der Voort, Nicolet (2014). "Umayyad Court". In Fitzpatrick, C.; Walker, A. (eds.). Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture: An Encyclopedia of the Prophet of God. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-177-2.

- Crone, Patricia (17 July 1980). Slaves on Horses: The Evolution of the Islamic Polity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521229616.

- Crone, Patricia; Cook, M. A.; Cook, Michael (21 April 1977). Hagarism: The Making of the Islamic World. CUP Archive. ISBN 9780521211338.

External links

Media related to Umayyad Caliphate at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Umayyad Caliphate at Wikimedia Commons