Human vestigiality

In the context of human evolution, human vestigiality involves those traits occurring in humans that have lost all or most of their original function through evolution. Although structures called vestigial often appear functionless, a vestigial structure may retain lesser functions or develop minor new ones. In some cases, structures once identified as vestigial simply had an unrecognized function. Vestigial organs are sometimes called rudimentary organs.[1] Many human characteristics are also vestigial in other primates and related animals.

History

In 1893,

- the role of the pineal in the regulation of the circadian rhythm (neither the function nor even the existence of melatonin was yet known);

- discovery of the role of the thymus in the immune system lay many decades in the future; it remained a mystery organ until after the mid-20th century;

- the pituitary and hypothalamus with their many and varied hormones were far from understood, let alone the complexity of their interrelationships.

Historically, there was a trend not only to dismiss the appendix as being uselessly vestigial, but an anatomical hazard, a liability to dangerous inflammation. As late as the mid-20th century, many reputable authorities conceded it no beneficial function.[7] This was a view supported, or perhaps inspired, by Darwin himself in the 1874 edition of his book The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. The organ's patent liability to appendicitis and its poorly understood role left the appendix open to blame for a number of possibly unrelated conditions. For example, in 1916, a surgeon claimed that removal of the appendix had cured several cases of trifacial neuralgia and other nerve pain about the head and face, even though he stated that the evidence for appendicitis in those patients was inconclusive.[8] The discovery of hormones and hormonal principles, notably by Bayliss and Starling, argued against these views, but in the early twentieth century, there remained a great deal of fundamental research to be done on the functions of large parts of the digestive tract. In 1916, an author found it necessary to argue against the idea that the colon had no important function and that "the ultimate disappearance of the appendix is a coordinate action and not necessarily associated with such frequent inflammations as we are witnessing in the human".[9]

There had been a long history of doubt about such dismissive views. Around 1920, the prominent surgeon Kenelm Hutchinson Digby documented previous observations, going back more than thirty years, that suggested lymphatic tissues, such as the tonsils and appendix, may have substantial immunological functions.

Anatomical

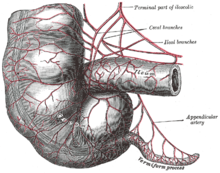

Appendix

In modern humans, the

Some herbivorous animals, such as rabbits, have a terminal vermiform appendix and

A 2013 study, however, refutes the idea of an inverse relationship between cecum size and appendix size and presence. It is widely present in

Coccyx

The

The tailbone, located at the end of the spine, has lost its original function in assisting balance and mobility, though it still serves some secondary functions, such as being an attachment point for muscles, which explains why it has not degraded further.In rare cases, congenital defect results in a short tail-like structure being present at birth. Twenty-three cases of human babies born with such a structure have been reported in the medical literature since 1884.[22][23] In rare cases such as these, the spine and skull were determined to be entirely normal. The only abnormality was that of a tail approximately twelve centimeters long. These tails, though of no deleterious effect, were almost always surgically removed.[24]

Wisdom teeth

Vomeronasal organ

In some animals, the

Among studies that use microanatomical methods, there is no reported evidence that human beings have active sensory neurons like those in working vomeronasal systems of other animals.[36][37] Furthermore, there is no evidence to date that suggests there are nerve and axon connections between any existing sensory receptor cells that may be in the adult human VNO and the brain.[38] Likewise, there is no evidence for any accessory olfactory bulb in adult human beings,[36] and the key genes involved in VNO function in other mammals have become pseudogenes in human beings. Therefore, while the presence of a structure in adult human beings is debated, a review of the scientific literature by Tristram Wyatt concluded, "most in the field ... are sceptical about the likelihood of a functional VNO in adult human beings on current evidence."[39]

Ear

The

The outer structure of the ear also shows some vestigial features, such as the node or point on the helix of the ear known as Darwin's tubercle which is found in around 10% of the population.

Eye

The plica semilunaris is a small fold of tissue on the inside corner of the eye. It is the vestigial remnant of the nictitating membrane, i.e., third eyelid, an organ that is fully functional in some other species of mammals.[43] Its associated muscles are also vestigial.[10] Only one species of primate, the Calabar angwantibo, is known to have a functioning nictitating membrane.[44]

The orbitalis muscle is a vestigial or rudimentary nonstriated muscle (smooth muscle) of the eye that crosses from the infraorbital groove and sphenomaxillary fissure and is intimately united with the periosteum of the orbit. It was described by Johannes Peter Müller and is often called Müller's muscle. The muscle forms an important part of the lateral orbital wall in some animals, but in humans it is not known to have any significant function.[45][46]

Reproductive system

Genitalia

In the

Human vestigial structures also include leftover embryological remnants that once served a function during development, such as the belly button, and analogous structures between biological sexes. For example, men are also born with two nipples, which are not known to serve a function compared to women.[47] In regards to genitourinary development, both internal and external genitalia of male and female fetuses have the ability to fully or partially form their analogous phenotype of the opposite biological sex if exposed to a lack/overabundance of androgens or the SRY gene during fetal development.[48][49] Examples of vestigial remnants of genitourinary development include the hymen, which is a membrane that surrounds or partially covers the external vaginal opening that derives from the sinus tubercle during fetal development and is homologous to the male seminal colliculus.[50] Some researchers[who?] have hypothesized that the persistence of the hymen may be to provide temporary protection from infection, as it separates the vaginal lumen from the urogenital sinus cavity during development.[51] Other examples include the glans penis and the clitoris, the labia minora and the ventral penis, and the ovarian follicles and the seminiferous tubules.[50]

In modern times, there is controversy regarding whether the foreskin is a vital or vestigial structure.[52] In 1949, British physician Douglas Gairdner noted that the foreskin plays an important protective role in newborns. He wrote, "It is often stated that the prepuce is a vestigial structure devoid of function ... However, it seems to be no accident that during the years when the child is incontinent the glans is completely clothed by the prepuce, for, deprived of this protection, the glans becomes susceptible to injury from contact with sodden clothes or napkin."[52] During the physical act of sex, the foreskin reduces friction, which can reduce the need for additional sources of lubrication.[52] "Some medical researchers, however, claim circumcised men enjoy sex just fine and that, in view of recent research on HIV transmission, the foreskin causes more trouble than it's worth."[52] The area of the outer foreskin measures between 7 and 100 cm2,[53] and the inner foreskin measures between 18 and 68 cm2,[54] which is a wide range. Regarding vestigial structures, Charles Darwin wrote, "An organ, when rendered useless, may well be variable, for its variations cannot be checked by natural selection."[55]

Musculature

A number of

Head

The occipitalis minor is a muscle in the back of the head which normally joins to the

The

Face

In many lower animals, the upper lip and sinus area is associated with whiskers or vibrissae which serve a sensory function. In humans, these whiskers do not exist but there are still sporadic cases where elements of the associated vibrissal capsular muscles or sinus hair muscles can be found. Based on histological studies of the upper lips of 20 cadavers, Tamatsu et al. found that structures resembling such muscles were present in 35% (7/20) of their specimens.[58]

Arm

The

The levator claviculae muscle in the posterior triangle of the neck is a supernumerary muscle present in only 2–3% of all people[62] but nearly always present in most mammalian species, including gibbons and orangutans.[63]

Torso

The

The

Leg

The plantaris muscle is composed of a thin muscle belly and a long thin tendon. The muscle belly is approximately 5–10 centimetres (2–4 inches) long, and is absent in 7–10% of the human population. It has some weak functionality in moving the knee and ankle but is generally considered redundant and is often used as a source of tendon for grafts. The long, thin tendon of the plantaris is humorously called "the freshman's nerve", as it is often mistaken for a nerve by new medical students.

Tongue

Another example of human vestigiality occurs in the tongue, specifically the

Breasts

Behavioral

Humans also bear some vestigial behaviors and reflexes.[72]

Goose bumps

The formation of

Palmar grasp reflex

The palmar grasp reflex is thought to be a vestigial behavior in human infants. When placing a finger or object to the palm of an infant, it will securely grasp it. This grasp is found to be rather strong.[74] Some infants—37% according to a 1932 study—are able to support their own weight from a rod,[75] although there is no way they can cling to their mother. The grasp is also evident in the feet. When a baby is sitting down, its prehensile feet assume a curled-in posture, similar to that observed in an adult chimp.[76][77] An ancestral primate would have had sufficient body hair to which an infant could cling, unlike modern humans, thus allowing its mother to escape from danger, such as climbing up a tree in the presence of a predator without having to occupy her hands holding her baby.

Hiccup

It has been proposed that the hiccup is an evolutionary remnant of earlier amphibian respiration.[78] Amphibians such as tadpoles gulp air and water across their gills via a rather simple motor reflex akin to mammalian hiccuping. The motor pathways that enable hiccuping form early during fetal development, before the motor pathways that enable normal lung ventilation form. Additionally, hiccups and amphibian gulping are inhibited by elevated CO2 and may be stopped by GABAB receptor agonists, illustrating a possible shared physiology and evolutionary heritage. These proposals may explain why premature infants spend 2.5% of their time hiccuping, possibly gulping like amphibians, as their lungs are not yet fully formed. Fetal intrauterine hiccups are of two types. The physiological type occurs before 28 weeks after conception and tend to last five to ten minutes. These hiccups are part of fetal development and are associated with the myelination of the phrenic nerve, which primarily controls the thoracic diaphragm. The phylogeny hypothesis explains how the hiccup reflex might have evolved, and if there is not an explanation, it may explain hiccups as an evolutionary remnant, held-over from our amphibious ancestors. This hypothesis has been questioned because of the existence of the afferent loop of the reflex, the fact that it does not explain the reason for glottic closure, and because the very short contraction of the hiccup is unlikely to have a significant strengthening effect on the slow-twitch muscles of respiration.[citation needed]

Pseudogenes

There are many

See also

References

- ^ "Difference between rudimentary and vestigial organ - Biology - Evolution - 11741123 | Meritnation.com". www.meritnation.com. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ Darwin C, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, London: John Murray, 1890, p.13.[1]

- ^ Turner W, On the musculus sternalis, Proc. Royal Soc. Edinburgh session 1866–1867, p.65.[2]

- ^ Wiedersheim, R. (1893) The Structure of Man: An Index to His Past History. Second Edition. Translated by H. and M. Bernard. London: Macmillan and Co. 1895. [3]

- ^ Muller, G. B. (2002). "Vestigial Organs and Structures". In Pagel, Mark (ed.). Encyclopedia of Evolution. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 1131–1133.

- ^ Koerth-Baker, Maggie (30 July 2009). "Vestigial Organs Not So Useless After All". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 4 August 2009. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ^ a b Wells, H. G.; Huxley, J.; Wells, G. P. (1929). The Science of Life. Cassells.

- ^ Rosenthal, M. I.: Journal of the American Medical Association, Volume 67, Issues 15–26, 1916. p. 1326

- ^ W. Colin MacKenzie. "A Contribution to the Biology of the Vermiform Appendix". Medical Record, Volume 89, p. 342, 1916

- ^ a b c d Darwin, Charles (1871). The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex. John Murray: London.

- PMID 27271818.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-521-61714-7.

- ISBN 978-1-84593-631-0

- ^ "Appendix may be useful after all – Health – Health care – More health news – NBC News". NBC News.

- PMID 17936308.

- ^ Charles Q. Choi, "The Appendix: Useful and in Fact Promising", Live Science, 2009, Appendix has useful function

- PMID 19678866.

- )

- PMID 8059973.

- PMID 677043.

- PMID 6373560.

- PMID 3284435.

- PMID 3894599.

- ^ Johnson, Dr. George B. "Evidence for Evolution" Archived 10 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine. (Page 12) Txtwriter Inc. 8 June 2006.

- PMID 11220165.

- PMID 16585527.

- PMID 10944499.

- PMID 8653495.

- PMID 11519019.

- PMID 11117628.

- PMID 10969469.

- PMID 4068105.

- PMID 19161592.

- PMID 11554506.

- ^ S2CID 25630359.

- PMID 16487792.

- PMID 15470677.

- ISBN 978-0-521-48526-5.

- ^ Prof. A. Macalister, Annals and Magazine of Natural History, vol. vii., 1871, p. 342.

- .

- ^ Mr. St. George Mivart, Elementary Anatomy, 1873, p. 396.

- ^ Owen, R. 1866–1868. Comparative Anatomy and Physiology of Vertebrates. London.[page needed]

- PMID 5971502.

- PMID 653491.

- ^ Dutton, J.J., Atlas of Clinical and Surgical Orbital Anatomy, 2nd Edition, Elsevier, 2011. p.116-117.

- ^ "Breast Anatomy and Embryology". Essentials of Plastic Surgery (2015): 355–361

- PMID 7965425.

- PMID 26761946.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-540-85601-6.

- PMID 19646660.

- ^ PMID 22025652.

- ^ Kigozi G, Wawer M, Ssettuba A, et al. "Foreskin surface area and HIV acquisition in Rakai, Uganda (size matters)". AIDS. 2009; 23(16):2209–2213. 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328330eda8.

- ^ Werker PMN, Terng ASC, Kon M. "The prepuce free flap: dissection feasibility study and clinical application of a super-thin new flap". Plastic Reconstructive Surgery. 1998; 102(4):1075–1082. 10.1097/00006534-199809020-00024.

- ^ Darwin C. The Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. London, UK: John Murray; 1859.

- JSTOR 30079154.

- PMID 15381582.

- S2CID 21055062.

- PMID 24860810.

- S2CID 25324691.

- S2CID 35394120.

- PMID 10319965.

- PMID 19085875.

- PMID 19159363.

- S2CID 221547558.

- ^ Edwards, William E., The Musculoskeletal Anatomy of the Thorax and Brachium of an Adult Female Chimpanzee,6571st Aeromedical Research Laboratory, New Mexico, 1965. http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/462433.pdf Archived 11 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Anatomy Atlases: Illustrated Encyclopedia of Human Anatomic Variation: Opus I: Muscular System: Alphabetical Listing of Muscles: L:Latissimus Dorsi".

- PMID 12392330.

- ^ Kajava, Y (1915). "The proportions of supernumerary nipples in the Finnish population". Duodecim. 1: 143–70.

- PMID 23716953.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of March 2024 (link - PMID 34667697.

- ^

- ^ Darwin, Charles. (1872) The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals John Murray, London.[page needed]

- ISBN 978-0-7167-0617-5.

- ^ Behavior Development in Infants (via Google Books) by Evelyn Dewey, citing a study "Reflexes and other motor activities in newborn infants: a report of 125 cases as a preliminary study of infant behavior" published in the Bull. Neurol. Inst. New York, 1932, Vol. 2, pp. 1–56.

- ISBN 978-0-670-02053-9.

- ISBN 978-0-7100-0980-7.

- PMID 12539245.

- PMID 10572964.

- PMID 8175804.

Further reading

- ISBN 978-0-307-27745-9.