Institut für Sexualwissenschaft

| Other name | Institute for Sexual Science |

|---|---|

| Motto | "Per scientiam ad justitiam" |

| Motto in English | "Through science to justice" |

| Founder(s) | Transgender healthcare Transgender studies |

| Address | In den Zelten 9A-10, Beethovenstraße 3 |

| Location | , , |

| Coordinates | 52°31′08″N 13°21′55″E / 52.5189°N 13.3652°E |

| Dissolved | May 6, 1933 |

The Institut für Sexualwissenschaft was an early private

The Institute was headed by

The institute pioneered research and treatment for various matters regarding gender and sexuality, including

The

Origins and purpose

The Institute of Sex Research was founded by

As well as being a research library and housing a large archive, the institute also included medical, psychological, and ethnological divisions, and a marriage and sex counseling office.

In addition, the institute advocated sex education,

Organization

The institute was financed by the Magnus-Hirschfeld-Foundation, a charity which itself was funded by private donations.[17] Along with Magnus Hirschfeld, a number of others (including many professional specialists) worked on the staff of the institute at different points in time, including:[27]

|

|

Some others worked for the institute in various domestic affairs.[27] Some of the people who worked at the institute simultaneously lived there, including Hirschfeld and Giese.[17] Affiliated groups held offices at the institute. This included the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, Helene Stöcker's Deutscher Bund für Mutterschutz und Sexualreform, and the World League for Sexual Reform (WLSR).[31][20][17] The WLSR has been described as the "international face" of the institute.[32] In 1929 Hirschfeld presided over the third international congress of the WLSR at Wigmore Hall.[33][34] During his address there, he stated that "A sexual impulse based on science is the only sound system of ethics."[25]

Divisions for the institute included ones dedicated to sexual biology, pathology, sociology and ethnography. Plans were allotted for the institute to both research and practice medicine in equal measure, though by 1925 a lack of funding meant the institute had to cut its medical research. This was to include matters of sexuality, gender, venereal disease, and birth control.[35]

Activity

Public education

The institute aimed to educate both the general public and specialists on its topics of focus.[6] It became a point of scientific and research interest for many scientists of sexuality, as well as intellectuals and reformers from all over the world.[20][11] Visitors included René Crevel, Christopher Isherwood, Harry Benjamin, Édouard Bourdet, Margaret Sanger, Francis Turville-Petre, André Gide and Jawaharlal Nehru.[11][20][17]

The institute also received visits from national governments; in 1923 the institute was for instance visited by Nikolai Semashko, Commissar for Health in the Soviet Union.[20] This was followed by numerous visits and research trips by health officials, political, sexual and social reformers, and scientific researchers from the Soviet Union interested in the work of Hirschfeld.[32] In June 1926 a delegation from the institute, led by Hirschfeld, reciprocated with a research visit to Moscow and Leningrad.[36][32]

One particular fixture at the institute which aided its popularity was its museum of sexual subjects. This was built with both education and entertainment in mind. There were ethnographic displays about different

The neighboring property purchased in 1922 by the institute had an opening ceremony on 5 March 1922, after which it became a place for the institute's staff to interact with the public in an educational capacity.[19] Lectures and question-and-answer sessions were held there to inform laypersons on topics of sexuality.[19][40] The public especially tended to ask questions regarding contraception.[40]

Sexual and reproductive health

One focus of the institute's research and services was

Sexual intermediacy

At the institute, Magnus Hirschfeld championed the doctrine of sexual intermediacy. This proposed form of classification said that every human trait existed on a scale from masculine to feminine. Masculine traits were characterized as dominant and active while feminine traits were passive and perceptive (an idea similar to those also commonly held by his contemporaries). The classification was further divided into the subgroups of

Transsexuality and transvestism

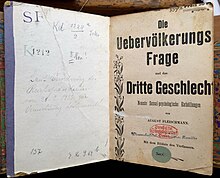

Magnus Hirschfeld coined the term transsexual in the 1923 essay Die Intersexuelle Konstitution.

Transgender people were on the staff of the institute as

Ludwig Levy-Lenz, the institute's primary surgeon for transsexual patients, also implemented an early form of facial feminization surgery and facial masculinization surgery.[53] Additionally, hair removal treatments using the institute's X-ray facility were developed, though this caused some side effects such as skin burns.[53] Professor of history Robert M. Beachy stated that, "Although experimental and, ultimately, dangerous, these sex-reassignment procedures were developed largely in response to the ardent requests of patients."[55] Levy-Lenz commented, "[N]ever have I operated upon more grateful patients."[55]

Hirschfeld worked with Berlin's police department to curtail the arrest of cross-dressers and transgender people, through the creation of transvestite passes. These were issued on behalf of the institute to those who had a personal desire to wear clothing associated with a gender other than the one assigned to them at birth.[56][57][20]

Homosexuality

A compilation of works about homosexuality could be found at the institute. The institute's collections included the first comprehensive such compilation of works about sexuality.[11][58] Different from the Others, a film co-written by Hirschfeld that advocated greater tolerance for homosexuals, was screened at the institute in 1920 to audiences of statesmen.[59] It also received a screening at the institute before a Soviet delegation in 1923, who responded with "amazement" that the film had been considered scandalous enough to censor.[32]

Working off of the research of

The institute put adaption therapy into practice as a far more humane and effective method than conversion therapy, as a means of helping patients cope with their sexuality. Rather than attempting to cure a patient's homosexuality, the focus was instead placed on helping the patient learn to navigate a homophobic society with the least discomfort possible. While the doctors at the institute could not outright recommend illegal practices (and, at this time, most all homosexual acts were illegal in Germany), they also did not promote abstinence. They made an effort to help their gay patients find a sense of community, either with other patients, through the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, or through a network of venues known to the institute that were aimed at gay men, lesbians, and cross-dressers.[63][11][64] Additionally, the institute offered them general psychological and medical assistance.[11]

Intersexuality

The institute presented expert reports about cases of intersex conditions.[14][50] Hirschfeld is considered to have been a pioneer in this area of study.[49] He advocated for the right of intersex individuals born with ambiguous genitalia to choose their own sex upon reaching the age of eighteen, and indeed assisted intersex people in attaining sex reassignment surgeries.[65][66] However, he sometimes also advocated strategic sex assignment at birth, on a scientific basis.[65] Photographs of intersex cases were among the collections at the institute – these were used as part of an effort to demonstrate sexual intermediacy to the average layperson.[17]

Nazi era

Background

From about the early 1920s onward, Hirschfeld became a target of the far-right in Germany, including the Nazi Party. He was physically attacked during multiple incidents, including an incident in Munich on 4 October 1920 in which he was badly injured. Deutschnationale Jugendzeitung, a nationalist paper, commented that it was "regrettable" Hirschfeld had not died. In another incident in Vienna, he was shot at. By 1929, frequent targeting by Nazis made it difficult for Hirschfeld to continue with his appearances in public.[11][9] A caricature of him appeared on the front page of Der Stürmer in February 1929; the Nazi Party attacked his Jewish ancestry as well as his theories about sex, gender, and sexuality.[9]

In late February 1933, as the influence of

Raids and book burnings

On 6 May 1933, while Hirschfeld was in

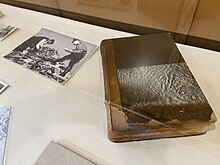

Four days later, the institute's remaining library and archives were publicly hauled out and

This included artistic works, rare medical and anthropological documents, and charts concerning cases of

The bronze bust of Hirschfeld survived. A

Aftermath of raids

A newspaper headline soon after the raids declared the "un-German Spirit" (or undeutschen Geist) of the institute. It was forced to shut down.[9] The Nazis took control of the buildings for their own purposes.[71] The destruction of the institute preceded a wider campaign against sexual reform and contraception, which were perceived as a threat to the German birth rate.[70] While many fled into exile, the radical activist Adolf Brand made a stand in Germany for five months after the book burnings, but in November 1933 he had given up gay activism.[76]

On 28 June 1934, Hitler conducted a purge of gay men in the ranks of the SA wing of the Nazis, which involved murdering them in the Night of the Long Knives. This was then followed by stricter laws on homosexuality and the round-up of gay men. The address lists seized from the Institute are believed to have aided Hitler in these actions. Many tens of thousands of arrestees found themselves, ultimately, in slave-labour or death camps. That included some of the institute's staff, such as August Bessunger.[77] Karl Giese committed suicide in 1938 when the Germans invaded Czechoslovakia; his heir, lawyer Karl Fein, was murdered in 1942 during deportation. Arthur Kronfeld and Felix Abraham also committed suicide.[77] Many survived by fleeing Germany. Among them were Berndt Götz, Ludwig Levy-Lenz, Bernard Schapiro, and Max Hodann.[77]

A handful of staff for the institute stayed behind during Nazi rule, such as Hans Graaz. Friedrich Hauptstein, Arthur Röser and Ewald Lausch even became

After World War II

The charter of the institute had specified that in the event of dissolution, any assets of the Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld Foundation (which had sponsored the institute since 1924) were to be donated to the Humboldt University of Berlin. Hirschfeld also wrote a personal will while in exile in Paris, leaving any remaining assets to his students and heirs Karl Giese and Li Shiu Tong (Tao Li) for the continuation of his work. However, neither stipulation was carried out. The West German courts found that the foundation's dissolution and the seizure of property by the Nazis in 1934 was legal. The West German legislature also retained the Nazi amendments to Paragraph 175, making it impossible for surviving gay men to claim restitution for the destroyed cultural center.[81]

Li Shiu Tong lived in Switzerland and the United States until 1956, but as far as is known, he did not attempt to continue Hirschfeld's work. Some remaining fragments of data from the library were later collected by W. Dorr Legg and ONE, Inc. in the United States in the 1950s.

Later developments

In 1973, a new Institut für Sexualwissenschaft was opened at the University of Frankfurt am Main (director: Volkmar Sigusch), and 1996 at the Humboldt University of Berlin.

References

Notes

- ^ Wolff 1986, p. 180.

- ISBN 978-1-4129-0916-7.

- ^ Beachy 2014, pp. 160–161.

- ISBN 978-1-56023-008-3. Alt URL

- ^ a b c Strochlic, Nina (28 June 2022). "The great hunt for the world's first LGBTQ archive". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 5 July 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ a b Beachy 2014, pp. 160–164.

- ^ Wolff 1986, p. 181.

- ^ "Institute of Sexology". Qualia Folk. 8 December 2011. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "Magnus Hirschfeld". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ Marhoefer, Laurie (21 September 2023). "New Research Reveals How the Nazis Targeted Transgender People". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 14 March 2024.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-87586-357-3.

- ^ "Arthur Kronfeld". Internet Publikation für Allgemeine und Integrative Psychotherapie. Archived from the original on 8 August 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ISBN 978-3-030-65813-7.

- ^ a b "Magnus Hirschfeld and HKW". Haus der Kulturen der Welt. Archived from the original on 9 November 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- Deutsches Historisches Museum Blog. Archivedfrom the original on 21 November 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-505672-3.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-137-36766-2. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ a b Beachy 2014, p. 161.

- ^ a b c Wolff 1986, p. 182.

- ^ PMID 16482697.

- ^ Beachy 2014, p. ix.

- ISBN 978-3-11-088786-0.

- ^ "The queer crusader". 10 May 2017.

- ^ Wolff 1986, p. 177.

- ^ S2CID 142426128.

- ^ a b Beachy 2014, p. 86.

- ^ a b Dose 2014, pp. 53–55.

- ^ "Hans Graaz, M.D." Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-8394-5332-2.

- PMID 12703271.

- ^ a b Beachy 2014, p. 163.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-226-92254-6.

- ^ "League for Sexual Reform: International Congress Opened". The Times. No. 45303. 9 September 1929. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ "League for Sexual Reform". The Journal of the American Medical Association. 93 (16): 1234–1235. 19 October 1929. Archived from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 9 October 2022.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Beachy 2014, pp. 161–162.

- OCLC 696313936.

- ^ Beachy 2014, pp. 162–164.

- ^ Beachy 2014, p. 162.

- ISBN 978-0-399-11576-9– via the Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Beachy 2014, pp. 183–184.

- ISBN 978-1-118-89687-7. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- ^ a b Beachy 2014, p. 182.

- ^ Beachy 2014, p. 184.

- ^ Dose 2014, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Beachy 2014, pp. 169–170.

- ^ S2CID 210986290.

- The International Journal of Transgenderism. 5 (2). Archived from the originalon 28 April 2006.

- ^ PMID 35860172.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-317-15730-4.

- ^ S2CID 242987098.

- ^ Beachy 2014, pp. 177–178.

- ISBN 978-1-58005-690-8. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 10 October 2022.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link - ^ a b c Beachy 2014, pp. 176–178.

- ^ a b Beachy 2014, p. 175.

- ^ a b Beachy 2014, p. 178.

- ^ Beachy 2014, p. 106.

- ^ Beachy, Robert; Gross, Terry (17 December 2014). "Between World Wars, Gay Culture Flourished In Berlin". NPR. Retrieved 13 September 2017.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-135-94241-0. Alt URL

- ^ Beachy 2014, pp. 164–167.

- ^ Dose 2014, pp. 73–74.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-135-82502-7.

- ^ Beachy 2014, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Dose 2014, p. 75.

- ^ Beachy 2014, p. 180.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-230-30708-7.

- ISBN 978-0-472-12300-1. Archived from the original on 18 June 2023. Retrieved 9 October 2022.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link - ^ Neumann, Boaz (24 January 2019). "The Nazis tolerated gays. Then everything changed". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- S2CID 145767149.

- ISBN 978-1-4299-3693-4. Archived from the original on 27 October 2022. Retrieved 8 October 2022.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link - ^ OCLC 53186626.

- ^ a b c Beachy 2014, pp. 241–242.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4408-4084-5.

- ISBN 978-1-85109-372-4. Alt URL

- ^ "1933 Book Burnings". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- OCLC 43662080.

- ^ LaVey, Simon (1996). "Queer Science: The Use and Abuse of Research into Homosexuality". MIT Press. Retrieved 17 August 2020 – via The Washington Post.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-472-13035-1.

- ^ a b Beachy 2014, p. 242.

- ^ "Institute Employees and Domestic Personnel". Magnus-Hirschfeld-Gesellschaft. Retrieved 4 December 2022.

- ^ "The first Institute for Sexual Science (1919–1933)". www.magnus-hirschfeld.de. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- OCLC 1500143– via the Internet Archive.

Bibliography

- Dose, Ralf (2014). Magnus Hirschfeld: The Origins of the Gay Liberation Movement. New York University Press. OCLC 870272914.

- ISBN 978-0-307-47313-4.

- .

Further reading

- OpenLibrary.

- Blasius, Mark and Phelan, Shane ed. (1997) We Are Everywhere: A Historical Source Book of Gay and Lesbian Politics (See the chapter: "The Emergence of a Gay and Lesbian Political Culture in Germany" by James D. Steakley).

- Grau, Günter ed. (1995) Hidden Holocaust? Gay and Lesbian Persecution in Germany 1933–45.

- Lauritsen, John and Thorstad, David (1995) The Early Homosexual Rights Movement (1864–1935). (2nd ed. revised)

- Steakley, James D. (9 June 1983) "Anniversary of a Book Burning". pp. 18–19, 57. The Advocate (Los Angeles)

- Marhoefer, Laurie. (2015) Sex and the Weimar Republic: German Homosexual Emancipation and the Rise of the Nazis. University of Toronto Press.

- Taylor, Michael Thomas; Timm, Annette F.; Herrn, Rainer eds. (2017) Not Straight From Germany: Sexual Publics and Sexual Citizenship Since Magnus Hirschfeld. JSTOR 10.3998/mpub.9238370.

Film

- Rosa von Praunheim, director (Germany, 2001) The Einstein of Sex (A biographical drama about Magnus Hirschfeld – English subtitled version available).

External links

- "Institute for Sexual Science (1919–1933)" Online exhibition of the Magnus Hirschfeld Society – warning, complex JavaScript and pop-up windows.

- Documentation in the Archive for Sexology, Berlin

- When Books Burn Archived 2018-04-12 at the Wayback Machine – University of Arizona multimedia exhibit.