Isometric video game graphics

|

| Part of a series on |

| Video game graphics |

|---|

Isometric video game graphics are graphics employed in

Once common, isometric projection became less so with the advent of more powerful

Overview

Advantages

A well-executed isometric system should never have the player thinking about the camera. You should be able to quickly and intuitively move the view to what you need to look at and never consider the camera mechanics. Trying to run a full-3D camera while playing out a real-time tactical battle is certain to cause a

helmet firein new players as they are quickly overwhelmed by the mechanics.

Trent Oster, co-founder of BioWare and founder of Beamdog[1]

In the fields of

Further, though not limited strictly to isometric video game graphics,

Lastly, there are also gameplay advantages to using an isometric or near-isometric perspective in video games. For instance, compared to a purely

In the present day, rather than being purely a source of nostalgia, the revival of isometric projection is the result of real, tangible design benefits.[1]

Disadvantages

Some disadvantages of pre-rendered isometric graphics are that, as display resolutions and display aspect ratios continue to evolve, static 2D images need to be re-rendered each time in order to keep pace, or potentially suffer from the effects of pixelation and require anti-aliasing. Re-rendering a game's graphics is not always possible, however; as was the case in 2012, when Beamdog remade BioWare's Baldur's Gate (1998). Beamdog were lacking the original developers' creative art assets (the original data was lost in a flood[5]) and opted for simple 2D graphics scaling with "smoothing", without re-rendering the game's sprites. The results were a certain "fuzziness", or lack of "crispness", compared to the original game's graphics.[citation needed] This does not affect real-time rendered polygonal isometric video games, however, as changing their display resolutions or aspect ratios is trivial, in comparison.

Differences from "true" isometric projection

The projection commonly used in video games deviates slightly from "true" isometric due to the limitations of

History of isometric video games

Some

1980s

The use of isometric graphics in video games began with

Another early isometric game is

In February 1983,

In 1983, isometric games were no longer exclusive to the arcade market and also entered home computers, with the release of

A year later, the ZX Spectrum game

1990s

Throughout the 1990s several successful games such as

Also during the 1990s, isometric graphics began being used for Japanese role-playing video games (JRPGs) on console systems, particularly tactical role-playing games, many of which still use isometric graphics today. Examples include Front Mission (1995), Tactics Ogre (1995) and Final Fantasy Tactics (1997)—the latter of which used 3D graphics to create an environment where the player could freely rotate the camera. Other titles such as Vandal Hearts (1996) and Breath of Fire III (1997) carefully emulated an isometric or parallel view, but actually used perspective projection.

Isometric, or similar, perspectives become popular in

2010s

Isometric projection has seen continued relevance in the new millennium with the release of several newly-

The term "isometric perspective" is frequently misapplied to any game with an—usually fixed—angled, overhead view that appears at first to be "isometric". These include the aforementioned

Also, not all "isometric" video games rely solely on pre-rendered 2D sprites. There are, for instance, titles which use polygonal 3D graphics completely, but render their graphics using parallel projection instead of perspective projection, such as Syndicate Wars (1996), Dungeon Keeper (1997) and Depths of Peril (2007); games which use a combination of pre-rendered 2D backgrounds and real-time rendered 3D character models, such as The Temple of Elemental Evil (2003) and Torment: Tides of Numenera (2017); and games which combine real-time rendered 3D backgrounds with hand-drawn 2D character sprites, such as Final Fantasy Tactics (1997) and Disgaea: Hour of Darkness (2003).

One advantage of top-down oblique projection over other near-isometric perspectives, is that objects fit more snugly within non-overlapping square graphical tiles, thereby potentially eliminating the need for an additional Z-order in calculations, and requiring fewer pixels.

Mapping screen to world coordinates

One of the most common problems with programming games that use isometric (or more likely dimetric) projections is the ability to map between events that happen on the 2d plane of the screen and the actual location in the isometric space, called world space. A common example is picking the tile that lies right under the cursor when a user clicks. One such method is using the same rotation matrices that originally produced the isometric view in reverse to turn a point in screen coordinates into a point that would lie on the game board surface before it was rotated. Then, the world x and y values can be calculated by dividing by the tile width and height.

Another way that is less computationally intensive and can have good results if the method is called on every frame, rests on the assumption that a square board was rotated by 45 degrees and then squashed to be half its original height. A virtual grid is overlaid on the projection as shown on the diagram, with axes virtual-x and virtual-y. Clicking any tile on the central axis of the board where (x, y) = (tileMapWidth / 2, y), will produce the same tile value for both world-x and world-y which in this example is 3 (0 indexed). Selecting the tile that lies one position on the right on the virtual grid, actually moves one tile less on the world-y and one tile more on the world-x. This is the formula that calculates world-x by taking the virtual-y and adding the virtual-x from the center of the board. Likewise world-y is calculated by taking virtual-y and subtracting virtual-x. These calculations measure from the central axis, as shown, so the results must be translated by half the board. For example, in the C programming language:

float virtualTileX = screenx / virtualTileWidth;

float virtualTileY = screeny / virtualTileHeight;

// some display systems have their origin at the bottom left while the tile map at the top left, so we need to reverse y

float inverseTileY = numberOfTilesInY - virtualTileY;

float isoTileX = inverseTileY + (virtualTileX - numberOfTilesInX / 2);

float isoTileY = inverseTileY - (virtualTileX - numberOfTilesInY / 2);

This method might seem counter intuitive at first since the coordinates of a virtual grid are taken, rather than the original isometric world, and there is no one-to-one correspondence between virtual tiles and isometric tiles. A tile on the grid will contain more than one isometric tile, and depending on where it is clicked it should map to different coordinates. The key in this method is that the virtual coordinates are floating point numbers rather than integers. A virtual-x and y value can be (3.5, 3.5) which means the center of the third tile. In the diagram on the left, this falls in the 3rd tile on the y in detail. When the virtual-x and y must add up to 4, the world x will also be 4.

Examples

Dimetric projection

-

LinCity-NG (2005), a tile-based city-building game

Oblique projection

Perspective projection

-

real-time strategy video game.

-

UFO: Alien Invasion 2.4 tactical mode

See also

- Clipping

- Filmation engine

- Category:Video games with isometric graphics: listing of isometric video games

- Category:Video games with oblique graphics: listing of oblique video games

- Commons:Category:Isometric video game screenshots: gallery of isometric video game screenshots

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Signor, Jeremy (2014-12-19). "Retronauts: The Continued Relevance of Isometric Games". usgamer.net. Gamer Network. Archived from the original on 2015-08-09. Retrieved 2017-04-01.

- ^ a b Vas, Gergo (2013-03-18). "The Best-Looking Isometric Games". kotaku.com. Gizmodo Media Group. Retrieved 2017-04-01.

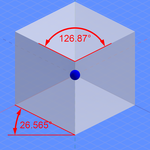

- ^ Note: the blue vectors point towards the camera positions. The red arcs represent the rotations around the horizontal and vertical axes. The white boxes match the ones shown in the images at the top of the article. Notice how in the left image the camera vector passes through the two opposing vertices of the cube.

- ^ Vas, Gergo (2013-05-10). "Video Games With The Most Memorable Pre-Rendered Backgrounds". Kotaku.com. Gizmodo Media Group. Retrieved 2017-04-01.

- ^ Grayson, Nathan (2016-04-01). "The Struggle To Bring Back Baldur's Gate After 17 Years". Kotaku.com. Gizmodo Media Group. Retrieved 2017-04-11.

It was a big challenge because all of the Baldur's Gate original assets like the 3D models that make up these sprites, the 3D models for the levels in the original game, these archives were lost.

- Killer List of Videogames

- ^ "Treasure Island (Registration Number PA0000187784)". United States Copyright Office. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-4990251215.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-415-96282-7. Retrieved 13 November 2022.

- Killer List of Videogames

- ^ "Zaxxon (Registration Number PA0000135301)". United States Copyright Office. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

- Killer List of Videogames

- Davis, Warren. "The Creation of Q*Bert". Coinop.org. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- Killer List of Videogames

- ^ "Sculptin the new shape of Spectrum games". Sinclair User (21). December 1983. Retrieved 2009-03-02.

- ^ "Soft Solid 3D Ant Attack". CRASH (1). February 1984. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ "Ultimate Play the Game – Company Lookback". Retro Micro Games Action – The Best of gamesTM Retro Volume 1. Highbury Entertainment. 2006. p. 25.

- ^ Steven Collins. "Game Graphics During the 8-bit Computer Era". Computer Graphics Newsletters. SIGGRAPH. Archived from the original on 2012-09-09. Retrieved 2007-08-16.

- . "Knight Lore was said to be the second most cloned piece of software after the word- processing program Word Star."

- ^ "Looking for an old angle". CRASH (51). April 1988. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- ^ Note: The 2:1 pixel pattern in the near-isometric image allows smoother lines than in the isometric one.

- Marketwire. May 2000. Archived from the originalon 2012-07-10. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- CNET Networks, Inc. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- ^ Butts, Steve (2003-09-09). "SimCity 4: Rush Hour Preview". IGN PC. IGN Entertainment, Inc. Archived from the original on September 20, 2003. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- Gamasutra. CMP Media LLC. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

- ^ Walker, Trey (2002-07-12). "Divine Divinity goes gold". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 2017-04-11.

- Future Publishing Limited. Retrieved 2007-12-13.

- Games Radar. Retrieved 2009-11-06.

- ^ Hamilton, Kirk (2014-07-03). "I'm Glad They're Still Making Games Like Divinity: Original Sin". Kotaku. Gizmodo Media Group. Retrieved 2017-04-11.

External links

- The classic 8-bit isometric games that tried to break the mould at Eurogamer.com

- The Best-Looking Isometric Games at Kotaku.com

- The Best Isometric Video Games at Kotaku.com