Amygdalin

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(2R)-[β-D-Glucopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-D-glucopyranosyloxy]phenylacetonitrile

| |

| Systematic IUPAC name

(2R)-Phenyl{[(2R,3R,4S,5S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-({[(2R,3R,4S,5S,6R)-3,4,5-trihydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxan-2-yl]oxy}methyl)oxan-2-yl]oxy}acetonitrile | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (

JSmol ) |

|

| 66856 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

ECHA InfoCard

|

100.045.372 |

| EC Number |

|

| MeSH | Amygdalin |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C20H27NO11 | |

| Molar mass | 457.429 |

| Melting point | 223-226 °C(lit.) |

| H2O: 0.1 g/mL hot, clear to very faintly turbid, colorless | |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Warning | |

| H302 | |

| P264, P270, P301+P312, P330, P501 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | A6005 |

| Related compounds | |

Related compounds

|

sambunigrin

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

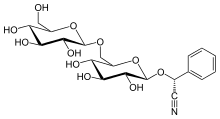

Amygdalin (from

Amygdalin is classified as a

Since the early 1950s, both amygdalin and a chemical derivative named laetrile have been promoted as alternative cancer treatments, often under the misnomer vitamin B17 (neither amygdalin nor laetrile is a vitamin).[2] Scientific study has found them to not only be clinically ineffective in treating cancer, but also potentially toxic or lethal when taken by mouth due to cyanide poisoning.[3] The promotion of laetrile to treat cancer has been described in the medical literature as a canonical example of quackery,[4][5] and as "the slickest, most sophisticated, and certainly the most remunerative cancer quack promotion in medical history".[2]

Chemistry

Amygdalin is a cyanogenic glycoside derived from the aromatic amino acid

Amygdalin is contained in

For one method of isolating amygdalin, the stones are removed from the fruit and cracked to obtain the kernels, which are dried in the sun or in ovens. The kernels are boiled in

Amygdalin is

Laetrile

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

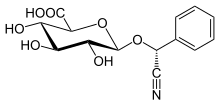

| IUPAC name

(2S,3S,4S,5R,6R)-6-[(R)-cyano(phenyl)methoxy]-3,4,5-trihydroxyoxane-2-carboxylic acid

| |

| Other names

L-mandelonitrile-β-D-glucuronide, Vitamin B17

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (

JSmol ) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

ECHA InfoCard

|

100.045.372 |

PubChem CID

|

|

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C14H15NO7 | |

| Molar mass | 309.2714 |

| Melting point | 214 to 216 °C (417 to 421 °F; 487 to 489 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Laetrile (patented 1961) is a simpler semisynthetic

Like amygdalin, laetrile is hydrolyzed in the duodenum (alkaline) and in the intestine (enzymatically) to D-glucuronic acid and L-mandelonitrile; the latter hydrolyzes to benzaldehyde and hydrogen cyanide, that in sufficient quantities causes cyanide poisoning.[16]

Claims for laetrile were based on three different hypotheses:[17] The first hypothesis proposed that cancerous cells contained copious beta-glucosidases, which release HCN from laetrile via hydrolysis. Normal cells were reportedly unaffected, because they contained low concentrations of beta-glucosidases and high concentrations of rhodanese, which converts HCN to the less toxic thiocyanate. Later, however, it was shown that both cancerous and normal cells contain only trace amounts of beta-glucosidases and similar amounts of rhodanese.[17]

The second proposed that, after ingestion, amygdalin was hydrolyzed to mandelonitrile, transported intact to the liver and converted to a beta-glucuronide complex, which was then carried to the cancerous cells, hydrolyzed by beta-glucuronidases to release mandelonitrile and then HCN. Mandelonitrile, however, dissociates to benzaldehyde and hydrogen cyanide, and cannot be stabilized by glycosylation.[18]: 9

Finally, the third asserted that laetrile is the discovered vitamin B-17, and further suggests that cancer is a result of "B-17 deficiency". It postulated that regular dietary administration of this form of laetrile would, therefore, actually prevent all incidences of cancer. There is no evidence supporting this conjecture in the form of a physiologic process, nutritional requirement, or identification of any deficiency syndrome.

History of laetrile

Early usage

Amygdalin was first isolated in 1830 from

In 1845 amygdalin was used as a cancer treatment in Russia, and in the 1920s in the United States, but it was considered too poisonous.[23] In the 1950s, a purportedly non-toxic, synthetic form was patented for use as a meat preservative,[24] and later marketed as laetrile for cancer treatment.[23]

The

Subsequent results

In a 1977 controlled, blinded trial, laetrile showed no more activity than placebo.[28]

Subsequently, laetrile was tested on 14 tumor systems without evidence of effectiveness. The

A 2015

The claims that laetrile or amygdalin have beneficial effects for cancer patients are not currently supported by sound clinical data. There is a considerable risk of serious adverse effects from cyanide poisoning after laetrile or amygdalin, especially after oral ingestion. The risk–benefit balance of laetrile or amygdalin as a treatment for cancer is therefore unambiguously negative.[3]

The authors also recommended, on ethical and scientific grounds, that no further clinical research into laetrile or amygdalin be conducted.[3]

Given the lack of evidence, laetrile has not been approved by the

The U.S. National Institutes of Health evaluated the evidence separately and concluded that clinical trials of amygdalin showed little or no effect against cancer.[23] For example, a 1982 trial by the Mayo Clinic of 175 patients found that tumor size had increased in all but one patient.[31] The authors reported that "the hazards of amygdalin therapy were evidenced in several patients by symptoms of cyanide toxicity or by blood cyanide levels approaching the lethal range."

The study concluded "Patients exposed to this agent should be instructed about the danger of cyanide poisoning, and their blood cyanide levels should be carefully monitored. Amygdalin (Laetrile) is a toxic drug that is not effective as a cancer treatment".

Additionally, "No controlled clinical trials (trials that compare groups of patients who receive the new treatment to groups who do not) of laetrile have been reported."[23]

The side effects of laetrile treatment are the symptoms of cyanide poisoning. These symptoms include: nausea and vomiting, headache, dizziness, cherry red skin color, liver damage, abnormally low blood pressure, droopy upper eyelid, trouble walking due to damaged nerves, fever, mental confusion, coma, and death.

The

Advocacy and legality of laetrile

Advocates for laetrile assert that there is a conspiracy between the US Food and Drug Administration, the pharmaceutical industry and the medical community, including the American Medical Association and the American Cancer Society, to exploit the American people, and especially cancer patients.[32]

Advocates of the use of laetrile have also changed the rationale for its use, first as a treatment of cancer, then as a vitamin, then as part of a "holistic" nutritional regimen, or as treatment for cancer pain, among others, none of which have any significant evidence supporting its use.[32]

Despite the lack of evidence for its use, laetrile developed a significant following due to its wide promotion as a "pain-free" treatment of cancer as an alternative to surgery and chemotherapy that have significant side effects. The use of laetrile led to a number of deaths.[32] The FDA and AMA crackdown, begun in the 1970s, effectively escalated prices on the black market, played into the conspiracy narrative and enabled unscrupulous profiteers to foster multimillion-dollar smuggling empires.[33]

Some American cancer patients have traveled to

Laetrile advocates in the United States include Dean Burk, a former chief chemist of the National Cancer Institute cytochemistry laboratory,[36] and national arm wrestling champion Jason Vale, who falsely claimed that his kidney and pancreatic cancers were cured by eating apricot seeds. Vale was convicted in 2004 for, among other things, fraudulently marketing laetrile as a cancer cure.[37] The court also found that Vale had made at least $500,000 from his fraudulent sales of laetrile.[38]

In the 1970s, court cases in several states challenged the FDA's authority to restrict access to what they claimed are potentially lifesaving drugs. More than twenty states passed laws making the use of laetrile legal. After the unanimous Supreme Court ruling in United States v. Rutherford[39] which established that interstate transport of the compound was illegal, usage fell off dramatically.[14][40] The US Food and Drug Administration continues to seek jail sentences for vendors marketing laetrile for cancer treatment, calling it a "highly toxic product that has not shown any effect on treating cancer."[41]

In popular culture

The

See also

- List of ineffective cancer treatments

- Alternative cancer treatments

References

- ^ "Apricot kernels pose risk of cyanide poisoning". European Food Safety Authority. 27 April 2016.

A naturally-occurring compound called amygdalin is present in apricot kernels and converts to hydrogen cyanide after eating. Cyanide poisoning can cause nausea, fever, headaches, insomnia, thirst, lethargy, nervousness, joint and muscle various aches and pains, and falling blood pressure. In extreme cases it is fatal

- ^ S2CID 28917628.

- ^ PMID 25918920.

- S2CID 36332694.

- PMID 6431478.

- PMID 27119432.

- (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- PMID 18192442.

- S2CID 22497338.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 900.

- PMID 26431391.

- ISBN 9788125013808. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ^ "Medical Management Guidelines (MMGs): Hydrogen Cyanide (HCN)". ATSDR. 21 October 2014. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ PMID 26389425. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- ISBN 978-1-4200-4479-9

- PMID 15635687.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8493-1279-3.

- ^ hdl:2164/7789.

- PMID 1154776.

- ^ "A chronology of significant historical developments in the biological sciences". Botany Online Internet Hypertextbook. University of Hamburg, Department of Biology. 18 August 2002. Archived from the original on 20 August 2007. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- S2CID 96869201.

- .

- ^ a b c d "Laetrile/Amygdalin". National Cancer Institute. 23 September 2005.

- ^ US 2985664, E Krebs, Ernst T. & Krebs, Jr., Ernst T., "Hexuronic acid derivatives", published 23 May 1961

- ISBN 978-0-691-14180-0.

- ^ Kennedy D (1977). "Laetrile: The Commissioner's Decision" (PDF). Federal Register. Docket No. 77-22310.

- S2CID 5932239.

- ^ PMID 17741690.

- ^ Budiansky S (9 July 1995). "Cures or Quackery: How Senator Harkin shaped federal research on alternative medicine". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

- S2CID 5896930.

Stock CC, Martin DS, Sugiura K, Fugmann RA, Mountain IM, Stockert E, Schmid FA, Tarnowski GS (1978). "Antitumor tests of amygdalin in spontaneous animal tumor systems". Journal of Surgical Oncology. 10 (2): 89–123.S2CID 22185766. - ^ "Laetrile (amygdalin, vitamin B17)". cancerhelp.org.uk. 30 August 2017.

- ^ )

- PMID 219680.

- PMID 15695477.

- ^ Lerner BH (15 November 2005). "McQueen's Legacy of Laetrile". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "Dean Burk, 84, Noted Chemist At National Cancer Institute, Dies". The Washington Post. 9 October 1988. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2007.

- ISBN 978-0-596-00732-4.

Jason Vale.

- ^ "New York Man Sentenced to 63 Months for Selling Fake Cancer Cure". Medical News Today. 22 June 2004. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ^ United States v. Rutherford, 442 U.S. 544 (United States Supreme Court 1979).

- PMID 7351911.

- ^ "Lengthy Jail Sentence for Vendor of Laetrile – A Quack Medication to Treat Cancer Patients". FDA. 22 June 2004. Archived from the original on 10 July 2009.