Nitrosopumilus

| Nitrosopumilus | |

|---|---|

| |

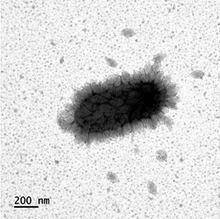

| Nitrosopumilus maritimus, partially with virions of Nitrosopumilus spindle-shaped virus 1 (Thaspiviridae) attached. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | Nitrososphaeria |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Nitrosopumilus Qin et al. 2017

|

| Type species | |

Nitrosopumilus maritimus Qin et al. 2017

| |

Species

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Nitrosopumilus maritimus is an extremely common

This organism was isolated from sediment in a tropical tank at the Seattle Aquarium by a group led by David Stahl (University of Washington).[5]

Biology

Lipid membranes

Populations of N. maritimus are probably the main source of

Cell division

Euryarchaeota, Thermoproteota, and Nitrososphaerota are some of the three major phyla of Archaea which use cell division to duplicate. Euryarchaeota and Bacteria use the FtsZ mechanism in cell division, while Thermoproteota divide using the Cdv machinery. However, Nitrososphaerota such as N. maritimus adopts both mechanisms, FtsZ and Cdv. Nevertheless, after further researches, N. maritimus was found to use mainly Cdv proteins rather than FtsZ during cell division. In this case, Cdv is the primary system in cell division for N. maritimus.[10][11] Therefore, to replicate a genome of 1.645Mb, N. maritimus spends 15 to 18 hours.[12]

Physiology

Genome

Ammonia Oxidizing

The isolation and the sequencing of N. maritimus's genome have allowed to extend the insight into the

•In the first one ammonia is oxidized through AMO forming the hydroxylamine; the latter, plus a molecule of nitric oxide, are, in turn, oxidized by a copper-based enzyme (Cu-ME) producing two molecules of nitrite. One of these is reduced to NO by the nitrite reductase (nirK) and goes back to the cu-ME enzyme. An electrons translocation occurs producing a Proton Motive Force (PMF) and allowing

•In the second one ammonia is oxidized through AMO making up the Hydroxylamine and then the two enzymes, nirK and Cu-ME, oxidize the hydroxylamine to nitric oxide and this to nitrite. The proper roles and the order at which these enzymes work, have to be clarified.

Additionally nitrous oxide is released by this type of metabolism. It is an important greenhouse gas that likely is produced as result of abiotic denitrification of metabolites.

Taxonomy

The currently accepted taxonomy is based on the List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN)[19] and National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI)[20]

| 16S rRNA based | 53 marker proteins based GTDB 08-RS214[24][25][26] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Ecology

Habitats

Characteristic of the Nitrososphaerota phylum, N. maritimus[27] is mainly found in oligotrophic (poor environment in nutrients) open ocean, within the Pelagic zone.[28] Initially discovered in Seattle, in an aquarium,[29] today N. maritimus can populate numerous environment such as the subtropical North Pacific and South Atlantic Ocean or the mesopelagic zone in the Pacific Ocean.[30] N. maritimus is an aerobic archeon able to grow even with an extremely low concentration of nutrients,[31] like in dark-deep open ocean, in which N. maritimus as an important impact.[32]

Contributions

Nitrification of the ocean

Members of the species N. maritimus can oxidize ammonia to form nitrite, which is the first step of the nitrogen cycle. Ammonia and nitrate are the two nutrients which form the inorganic pool of nitrogen. Populating poor environments (lacking of organic energy sources and sunlight), the oxidation of ammonia could contribute to primary productivity .[29] In fact, nitrate fuels half of the primary production of phytoplankton [33] but not only phytoplankton needs nitrate. The high ammonia's affinity allows N. maritimus to largely compete with the other marine phototrophs and chemotrophs.[31] Regarding the ammonium turnover per unit biomass, N. maritimus would be around 5 times higher than oligotrophic heterotrophs' turnover, and around 30 times higher than most of the oligotrophic diatoms known turnover.[31] Computing these two observations nitrification by N. maritimus plays a key role in the marine nitrogen cycle.[34]

Carbon and phosphorus implications

Its ability to fix inorganic carbon via an alternative pathway (3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate pathway)[28] allows N. maritimus to participate efficiently in the flux of the global carbon budget.[32] Coupling with the ammonia-oxidizing pathway, N. maritimus and the other marine thaumarchaea, approximately, recycle 4.5% of the organic carbon mineralized in the oceans and transform 4.3% of detrital phosphorus into new phosphorus substances.[32]

See also

References

- PMID 20421470.

- S2CID 4340386.

- ^ http://www.physorg.com/news173538255.html Planet's nitrogen cycle overturned by 'tiny ammonia eater of the seas' Hannah Hickey 2009-09-30 originally based on a Nature publication by Willm Martens-Habbena, David Stahl

- ISSN 0036-8075.

- S2CID 4340386.

- ^ .

- S2CID 25945482.

- .

- .

- ^ Ng, Kian-Hong, Vinayaka Srinivas, Ramanujam Srinivasan, and Mohan Balasubramanian. ‘The Nitrosopumilus Maritimus CdvB, but Not FtsZ, Assembles into Polymers’. Archaea 2013 (2013): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/104147.

- ^ Mosier, Annika C., Eric E. Allen, Maria Kim, Steven Ferriera, and Christopher A. Francis. ‘Genome Sequence of “ Candidatus Nitrosopumilus Salaria” BD31, an Ammonia-Oxidizing Archaeon from the San Francisco Bay Estuary’. Journal of Bacteriology 194, no. 8 (15 April 2012): 2121–22. https://doi.org/10.1128/JB.00013-12.

- ^ Pelve, Erik A., Ann-Christin Lindås, Willm Martens-Habbena, José R. de la Torre, David A. Stahl, and Rolf Bernander. ‘Cdv-Based Cell Division and Cell Cycle Organization in the Thaumarchaeon Nitrosopumilus maritimus: Cdv-Based Cell Division in N. Maritimus’. Molecular Microbiology 82, no. 3 (November 2011): 555–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07834.x.

- ^ Berg, Ivan A., Daniel Kockelkorn, Wolfgang Buckel, and Georg Fuchs. ‘A 3-Hydroxypropionate/4-Hydroxybutyrate Autotrophic Carbon Dioxide Assimilation Pathway in Archaea’. Science 318, no. 5857 (14 December 2007): 1782–86. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1149976.

- ^ Walker, C. B., J. R. de la Torre, M. G. Klotz, H. Urakawa, N. Pinel, D. J. Arp, C. Brochier-Armanet, et al. ‘Nitrosopumilus Maritimus Genome Reveals Unique Mechanisms for Nitrification and Autotrophy in Globally Distributed Marine Crenarchaea’. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107, no. 19 (11 May 2010): 8818–23.

- ^ The ISME Journal (2019) 13:2295–2305 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-019-0434-8

- ^ Madigan, Michael T., 1949- Brock biology of microorganisms / Michael T. Madigan. . . [et al.]. — Fourteenth edition. pages cm Includes index. ISBN 978-0-321-89739-8 1. Microbiology. I. Title. QR41.2.B77 2015 579–dc23

- ^ Hydroxylamine as an intermediate in ammonia oxidation by globally abundant marine archaea Neeraja Vajralaa,1, Willm Martens-Habbenab,1, Luis A. Sayavedra-Sotoa , Andrew Schauerc , Peter J. Bottomleyd , David A. Stahlb , and Daniel J. Arpa,2 Departments of a Botany and Plant Pathology and d Microbiology, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331; and Departments of b Civil and Environmental Engineering and c Earth and Space Science, University of Washington, Seattle, WA 98195 Edited by Edward F. DeLong, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, and approved December 7, 2012 (received for review August 17, 2012)

- ^ Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 2019, 49:9–15 This review comes from a themed issue on Bioinorganic chemistry Edited by Kyle M Lancaster For a complete overview see the Issue and the Editorial Available online 17th September 2018 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2018.09.003 1367-5931/ã 2018 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

- ^ J.P. Euzéby; et al. (1997). "Nitrosopumilus". List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN). Retrieved 2021-03-20.

- ^ Sayers; et al. "Nitrosopumilus". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) taxonomy database. Retrieved 2021-03-20.

- ^ "The LTP". Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ "LTP_all tree in newick format". Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ "LTP_06_2022 Release Notes" (PDF). Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ "GTDB release 08-RS214". Genome Taxonomy Database. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ "ar53_r214.sp_label". Genome Taxonomy Database. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ "Taxon History". Genome Taxonomy Database. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- ^ Brochier-Armanet, Céline, Bastien Boussau, Simonetta Gribaldo, and Patrick Forterre. “Mesophilic Crenarchaeota: Proposal for a Third Archaeal Phylum, the Thaumarchaeota.” Nature Reviews Microbiology 6, no. 3 (March 2008): 245–52. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro1852.

- ^ a b Walker, C. B., J. R. de la Torre, M. G. Klotz, H. Urakawa, N. Pinel, D. J. Arp, C. Brochier-Armanet, et al. “Nitrosopumilus Maritimus Genome Reveals Unique Mechanisms for Nitrification and Autotrophy in Globally Distributed Marine Crenarchaea.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107, no. 19 (May 11, 2010): 8818–23. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0913533107.

- ^ a b Könneke, Martin, Anne E. Bernhard, José R. de la Torre, Christopher B. Walker, John B. Waterbury, and David A. Stahl. “Isolation of an Autotrophic Ammonia-Oxidizing Marine Archaeon.” Nature 437, no. 7058 (September 2005): 543–46. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature03911.

- ^ Karner, Markus B., Edward F. DeLong, and David M. Karl. “Archaeal Dominance in the Mesopelagic Zone of the Pacific Ocean.” Nature 409, no. 6819 (January 2001): 507–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/35054051.

- ^ a b c Martens-Habbena, Willm, Paul M. Berube, Hidetoshi Urakawa, José R. de la Torre, and David A. Stahl. “Ammonia Oxidation Kinetics Determine Niche Separation of Nitrifying Archaea and Bacteria.” Nature 461, no. 7266 (October 2009): 976–79.

- ^ a b c Meador, Travis B., Niels Schoffelen, Timothy G. Ferdelman, Osmond Rebello, Alexander Khachikyan, and Martin Könneke. “Carbon Recycling Efficiency and Phosphate Turnover by Marine Nitrifying Archaea.” Science Advances 6, no. 19 (May 8, 2020): eaba1799. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aba1799.

- ^ Yool, Andrew, Adrian P. Martin, Camila Fernández, and Darren R. Clark. “The Significance of Nitrification for Oceanic New Production.” Nature 447, no. 7147 (June 2007): 999–1002. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature05885.

- ^ Wuchter, Cornelia, Ben Abbas, Marco J. L. Coolen, Lydie Herfort, Judith van Bleijswijk, Peer Timmers, Marc Strous, et al. “Archaeal Nitrification in the Ocean.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103, no. 33 (August 15, 2006): 12317–22. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0600756103.

Further reading

- Metcalf, W. W.; Griffin, B. M.; Cicchillo, R. M.; Gao, J.; Janga, S. C.; Cooke, H. A.; Circello, B. T.; Evans, B. S.; Martens-Habbena, W.; Stahl, D. A.; Van Der Donk, W. A. (2012). "Synthesis of Methylphosphonic Acid by Marine Microbes: A Source for Methane in the Aerobic Ocean". Science. 337 (6098): 1104–1107. PMID 22936780..

- Reitschuler, Christoph; Lins, Philipps; Wagner, Andreas Otto; Illmer, Paul (October 2014). "Cultivation of moonmilk-born non-extremophilic Thaum and Euryarchaeota in mixed culture". Anaerobe. 29 (1): 73–9. PMID 24513652.