Penetrating trauma

| Penetrating trauma | |

|---|---|

Birdshot pellets are visible in the wound, within the shattered patella. The powder wad from the shotgun shell has been extracted from the wound, and is visible at the upper right of the image. | |

| Specialty | Trauma surgery, General surgery, emergency medicine |

Penetrating trauma is an

A penetrating injury in which an object enters the body or a structure and passes all the way through an exit wound is called a perforating trauma, while the term penetrating trauma implies that the object does not perforate wholly through.[2] In gunshot wounds, perforating trauma is associated with an entrance wound and an often larger exit wound.

Penetrating trauma can be caused by a foreign object or by fragments of a broken bone. Usually occurring in

Penetrating trauma can be serious because it can damage internal organs and presents a risk of

Mechanism

As a missile passes through tissue, it decelerates, dissipating and transferring kinetic energy to the tissues.[1] The velocity of the projectile is a more important factor than its mass in determining how much damage is done;[1] kinetic energy increases with the square of the velocity. In addition to injury caused directly by the object that enters the body, penetrating injuries may be associated with secondary injuries, due for example to a blast injury.[2]

The path of a projectile can be estimated by imagining a line from the entrance wound to the exit wound, but the actual trajectory may vary due to ricochet or differences in tissue density.[4] In a cut, the discolouration and the swelling of the skin from a blow happens because of the ruptured blood vessels and escape of blood and fluid and other injuries that interrupt the circulation.[6]

Cavitation

Permanent

Low-velocity items, such as knives and swords, are usually propelled by a person's hand, and usually do damage only to the area that is directly contacted by the object.[7] The space left by tissue that is destroyed by the penetrating object as it passes through forms a cavity; this is called permanent cavitation.[8]

Temporary

High-velocity objects are usually

The characteristics of the tissue injured also help determine the severity of the injury; for example, the denser the tissue, the greater the amount of energy transmitted to it.[8] Skin, muscles, and intestines absorb energy and so are resistant to the development of temporary cavitation, while organs such as the liver, spleen, kidney, and brain, which have relatively low tensile strength, are likely to split or shatter because of temporary cavitation.[10] Flexible elastic soft tissues, such as muscle, intestine, skin, and blood vessels, are good energy absorbers and are resistant to tissue stretch. If enough energy is transferred, the liver may disintegrate.[9] Temporary cavitation can be especially damaging when it affects delicate tissues such as the brain, as occurs in penetrating head trauma.[citation needed]

Location

Head

While penetrating head trauma accounts for only a small percentage of all traumatic brain injuries (TBI), it is associated with a high mortality rate, and only a third of people with penetrating head trauma survive long enough to arrive at a hospital. Injuries from firearms are the leading cause of TBI-related deaths. Penetrating head trauma can cause cerebral contusions and lacerations, intracranial hematomas, pseudoaneurysms, and arteriovenous fistulas. The prognosis for penetrating head injuries varies widely.[11]

Penetrating

Chest

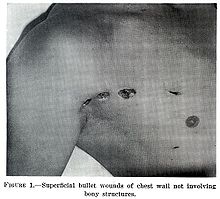

Most penetrating injuries are chest wounds and have a mortality rate (death rate) of under 10%.

Penetrating trauma can also cause injuries to the heart and circulatory system. When the heart is punctured, it may bleed profusely into the chest cavity if the membrane around it (the pericardium) is significantly torn, or it may cause pericardial tamponade if the pericardium is not disrupted.[15] In pericardial tamponade, blood escapes from the heart but is trapped within the pericardium, so pressure builds up between the pericardium and the heart, compressing the latter and interfering with its pumping.[15] Fractures of the ribs commonly produce penetrating chest trauma when sharp bone ends pierce tissues.

Abdomen

Penetrating

People with penetrating abdominal trauma may have signs of hypovolemic shock (insufficient blood in the circulatory system) and peritonitis (an inflammation of the peritoneum, the membrane that lines the abdominal cavity).[2] Penetration may abolish or diminish bowel sounds due to bleeding, infection, and irritation, and injuries to arteries may cause bruits (a distinctive sound similar to heart murmurs) to be audible.[2] Percussion of the abdomen may reveal hyperresonance (indicating air in the abdominal cavity) or dullness (indicating a buildup of blood).[2] The abdomen may be distended or tender, signs which indicate an urgent need for surgery.[2]

The standard management of penetrating abdominal trauma was for many years mandatory laparotomy. A greater understanding of mechanisms of injury, outcomes from surgery, improved imaging and interventional radiology has led to more conservative operative strategies being adopted.[16]

Assessment and treatment

Assessment can be difficult because much of the damage is often internal and not visible.

Negative pressure wound therapy is no more effective in preventing wound infection than standard care when used on open traumatic wounds.[18]

History

Before the 17th century, medical practitioners poured hot oil into wounds in order to cauterize damaged blood vessels, but the French surgeon Ambroise Paré challenged the use of this method in 1545.[19] Paré was the first to propose controlling bleeding using ligature.[19]

During the

In World War I, doctors began replacing patients' lost fluid with salt solutions.[2] With World War II came the idea of blood banking, having quantities of donated blood available to replace lost fluids. The use of antibiotics also came into practice in World War II.[2]

See also

- Aortic dissection

- Ballistic trauma

- Blunt splenic trauma

- Blunt trauma personal protective equipment

- Geriatric trauma

- Pediatric trauma

- Stab wound

- Transmediastinal gunshot wound

References

- ^ ISBN 3-13-140331-4. Retrieved 2008-06-12.

- ^ PMID 16962459.

- ISBN 3-13-140331-4. Retrieved 2008-06-12.

- ^ ISBN 0-7637-2046-1. Retrieved 2008-06-12.

Penetrating trauma.

- S2CID 23003890.

- ^ W. T. COUNCILMAN (1913). Disease and Its Causes. New York: New York Henry Holt and Company London Williams and Norgate The University Press, Cambridge, U.S.A.

- ^ a b c Daniel Limmer and Michael F. O'Keefe. 2005. Emergency Care 10th ed. Edward T. Dickinson, Ed. Pearson, Prentice Hall. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey. Pages 189-190.

- ^ ISBN 0-7817-2641-7.

- ^ PMID 19644779.

- S2CID 42707849. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2020-02-09.

- PMID 16962454.

- ^ ISBN 3-13-140331-4. Retrieved 2008-06-12.

- ISBN 0-7817-5035-0. Retrieved 2008-06-12.

- S2CID 29662985.

- ^ a b

Smith M, Ball V (1998). "Thoracic trauma". Cardiovascular/respiratory physiotherapy. St. Louis: Mosby. p. 220. ISBN 0-7234-2595-7. Retrieved 2008-06-12.

- ^ ISBN 9781444109627.

- ^ Advanced Trauma Life Support Student Course Manual (PDF) (9th ed.). American College of Surgeons. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 December 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- PMID 29969521.

- ^ PMID 16962459.

Prior to the 1600s, it was common practice was to pour hot oil into wounds to cauterize vessels and promote healing. This practice was questioned in 1545 by a French military surgeon named Ambroise Pare who also introduced the idea of using ligature to control hemorrhage.