Pythagoreanism

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Possibly some duplicate citations. Normalisation to CS1 citation style. (February 2025) |

Pythagoreanism originated in the 6th century BC, based on and around the teachings and beliefs held by Pythagoras and his followers, the Pythagoreans. Pythagoras established the first Pythagorean community in the ancient Greek colony of Kroton, in modern Calabria (Italy) circa 530 BC. Early Pythagorean communities spread throughout Magna Graecia.

Already during Pythagoras' life it is likely that the distinction between the akousmatikoi ("those who listen"), who is conventionally regarded as more concerned with religious, and ritual elements, and associated with the oral tradition, and the mathematikoi ("those who learn") existed. The ancient biographers of Pythagoras,

Following political instability in

As a philosophic tradition, Pythagoreanism was revived in the 1st century BCE, giving rise to

History

Pythagoras was already well known in ancient times for his supposed mathematical achievement of the Pythagorean theorem.[3] Pythagoras had been credited with discovering that in a right-angled triangle the square of the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two sides. In ancient times Pythagoras was also noted for his discovery that music had mathematical foundations. Antique sources that credit Pythagoras as the philosopher who first discovered music intervals also credit him as the inventor of the monochord, a straight rod on which a string and a movable bridge could be used to demonstrate the relationship of musical intervals.[4]

Much of the surviving sources on Pythagoras originated with Aristotle and the philosophers of the Peripatetic school, which founded historiographical academic traditions such as biography, doxography and the history of science. The surviving 5th century BC sources on Pythagoras and early Pythagoreanism are void of supernatural elements, while surviving 4th century BC sources on Pythagoras' teachings introduced legend and fable. Philosophers who discussed Pythagoreanism, such as Anaximander, Andron of Ephesus, Heraclides and Neanthes had access to historical written sources as well as the oral tradition about Pythagoreanism, which by the 4th century BC was in decline. Neopythagorean philosophers, who authored many of the surviving sources on Pythagoreanism, continued the tradition of legend and fantasy.[5]

The earliest surviving ancient source on Pythagoras and his followers is a satire by Xenophanes, on the Pythagorean beliefs on the transmigration of souls.[6] Xenophanes wrote of Pythagoras that:

Once they say that he was passing by when a puppy was being whipped,

And he took pity and said:

"Stop! Do not beat it! For it is the soul of a friend

That I recognised when I heard it giving tongue."[6]

In a surviving fragment from Heraclitus, Pythagoras and his followers are described as follows:

Pythagoras, the son of Mnesarchus, practised inquiry beyond all other men and selecting of these writings made for himself a wisdom or made a wisdom of his own: a polymathy, an imposture.[7]

Two other surviving fragments of ancient sources on Pythagoras are by Ion of Chios and Empedocles. Both were born in the 490s, after Pythagoras' death. By that time, he was known as a sage and his fame had spread throughout Greece.[8] According to Ion, Pythagoras was:

... distinguished for his manly virtue and modesty, even in death has a life which is pleasing to his soul, if Pythagoras the wise truly achieved knowledge and understanding beyond that of all men.[8]

Empedocles described Pythagoras as "a man of surpassing knowledge, master especially of all kinds of wise works, who had acquired the upmost wealth of understanding".[9] In the 4th century BC the Sophist Alcidamas wrote that Pythagoras was widely honored by Italians.[10]

Today scholars typically distinguish two periods of Pythagoreanism: early-Pythagoreanism, from the 6th until the 5th century BC, and late-Pythagoreanism, from the 4th until the 3rd century BC.

Early-Pythagorean sects were closed societies and new Pythagoreans were chosen based on merit and discipline. Ancient sources record that early-Pythagoreans underwent a five-year initiation period of listening to the teachings (akousmata) in silence. Initiates could through a test become members of the inner circle. However, Pythagoreans could also leave the community if they wished.[13] Iamblichus listed 235 Pythagoreans by name, among them 17 women whom he described as the "most famous" women practitioners of Pythagoreanism. It was customary that family members became Pythagoreans, as Pythagoreanism developed into a philosophic tradition that entailed rules for everyday life and Pythagoreans were bound by secrets. The home of Pythagoras was known as the site of mysteries.[14]

Pythagoras had been born on the island of

The anti-Pythagorean attacks in c. 508 BC were headed by

According to surviving sources by the

Philosophic traditions

Following Pythagoras' death, disputes about his teachings led to the development of two philosophical traditions within Pythagoreanism in Italy: akousmatikoi and mathēmatikoi. The mathēmatikoi recognised the akousmatikoi as fellow Pythagoreans, but because the mathēmatikoi allegedly followed the teachings of Hippasus, the akousmatikoi philosophers did not recognise them. Despite this, both groups were regarded by their contemporaries as practitioners of Pythagoreanism.[21]

The akousmatikoi were superseded in the 4th century BC as a significant

Akousmatikoi

The akousmatikoi believed that humans had to act in appropriate ways. The Akousmata (translated as "oral saying") was the collection of all the sayings of Pythagoras as divine dogma. The tradition of the akousmatikoi resisted any reinterpretation or philosophical evolution of Pythagoras' teachings. Individuals who strictly followed most akousmata were regarded as wise. The akousmatikoi philosophers refused to recognise that the continuous development of mathematical and scientific research conducted by the mathēmatikoi was in line with Pythagoras's intention. Until the demise of Pythagoreanism in the 4th century BC, the akousmatikoi continued to engage in a pious life by practicing silence, dressing simply and avoiding meat, for the purpose of attaining a privileged afterlife. The akousmatikoi engaged deeply in questions of Pythagoras' moral teachings, concerning matters such as harmony, justice,[24] ritual purity and moral behavior.McKirahan 2011, p. 90

Mathēmatikoi

The mathēmatikoi acknowledged the religious underpinning of Pythagoreanism and engaged in mathēma (translated as "learning" or "studying") as part of their practice. While their scientific pursuits were largely mathematical, they also promoted other fields of scientific study in which Pythagoras had engaged during his lifetime. A sectarianism developed between the dogmatic akousmatikoi and the mathēmatikoi, who in their intellectual activism became regarded as increasingly progressive. This tension persisted until the 4th century BC, when the philosopher Archytas engaged in advanced mathematics as part of his devotion to Pythagoras' teachings.[24]

Today, Pythagoras is mostly remembered for his mathematical ideas, and by association with the work early Pythagoreans did in advancing mathematical concepts and theories on harmonic

Rituals

Pythagoreanism was a philosophic tradition as well as a religious practice. As a religious community they relied on oral teachings and worshiped the

Philosophy

Early Pythagoreanism was based on research and the accumulation of knowledge from the books written by other philosophers.

Arithmetic and numbers

Pythagoras, in his teachings focused on the significance of

Early-Pythagorean philosophers such as Philolaus and Archytas held the conviction that mathematics could help in addressing important philosophical problems.[34] In Pythagoreanism numbers became related to intangible concepts. The one was related to the intellect and being, the two to thought, the number four was related to justice because 2 * 2 = 4 and equally even. A dominant symbolism was awarded to the number three, Pythagoreans believed that the whole world and all things in it are summed up in this number, because end, middle and beginning give the number of the whole. The triad had for Pythagoreans an ethical dimension, as the goodness of each person was believed to be threefold: prudence, drive and good fortune.[35]

Pythagoreans thought numbers existed "outside of [human] minds" and separate from the world.[36] They had many mystical and magical interpretations of the roles of numbers in governing existence.[36]

Geometry

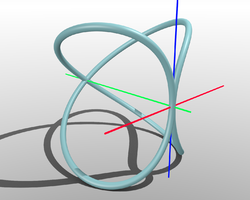

The Pythagoreans engaged with

Music

Pythagoras pioneered the mathematical and experimental study of music. He objectively measured physical quantities, such as the length of a

Pythagoras is credited with discovering that the most harmonious

The fact that mathematics could explain the human sentimental world had a profound impact on the Pythagorean philosophy. Pythagoreanism became the quest for establishing the fundamental essences of reality. Pythagorean philosophers advanced the unshakable belief that the essence of all things are numbers and that the universe was sustained by harmony.[38] According to ancient sources music was central to the lives of those practicing Pythagoreanism. They used medicines for the purification (katharsis) of the body and, according to Aristoxenus, music for the purification of the soul. Pythagoreans used different types of music to arouse or calm their souls,[41] and certain stirring songs could have notes that existed in the same ratio as the "distances of the heavenly bodies from the centre of" Earth.[36]

Harmony

For Pythagoreans, harmony signified the "unification of a multifarious composition and the agreement of unlike spirits". In Pythagoreanism, numeric harmony was applied in mathematical, medical, psychological, aesthetic, metaphysical and cosmological problems. For Pythagorean philosophers, the basic property of numbers was expressed in the harmonious interplay of opposite pairs. Harmony assured the balance of opposite forces.[42] Pythagoras had in his teachings named numbers and the symmetries of them as the first principle and called these numeric symmetries harmony.[43] This numeric harmony could be discovered in rules throughout nature. Numbers governed the properties and conditions of all beings and were regarded the causes of being in everything else. Pythagorean philosophers believed that numbers were the elements of all beings and the universe as a whole was composed of harmony and numbers.[35]

Unity and harmony is extended to all the opposites, which descent from the so-called Pythagorean "Table of ten Opposites", mentioned by Aristotle. Supreme opposites are the following ten couples: limit-unlimited, odd-even, one-many, right-left, male-female , rest-motion, straight-curved, light-darkness, good-evil, and square-oblong.[44]

Cosmology

The philosopher

Aristotle recorded in the 4th century BC on the Pythagorean astronomical system:

- It remains to speak of the earth, of its position, of the question whether it is at rest or in motion, and of its shape. As to its position, there is some difference of opinion. Most people–all, in fact, who regard the whole heaven as finite–say it lies at the center. But the Italian philosophers known as Pythagoreans take the contrary view. At the centre, they say, is fire, and the earth is one of the stars, creating night and day by its circular motion about the center. They further construct another earth in opposition to ours to which they give the name counterearth.[49]

It is not known whether Philolaus believed Earth to be round or flat,

Pythagoreans believed in a

Justice

Pythagoreans equated

I think human nature provides a common standard of law and justice for both the family and the city. Whoever follows the paths within and searches will discover; for within is law and justice, which is the proper arrangement of the soul.[53]

Body and soul

Pythagoreans believed that body and soul functioned together, and a healthy body required a healthy psyche.[54] Early Pythagoreans conceived of the soul as the seat of sensation and emotion. They regarded the soul as distinct from the intellect.[55] However, only fragments of the early Pythagorean texts have survived, and it is not certain whether they believed the soul was immortal. The surviving texts of the Pythagorean philosopher Philolaus indicate that while early Pythagoreans did not believe that the soul contained all psychological faculties, the soul was life and a harmony of physical elements. As such the soul passed away when certain arrangements of these elements ceased to exist.[56]

However, the teaching most securely identified with Pythagoras is

Vegetarianism

Some medieval authors refer to a "Pythagorean diet", entailing the abstention from eating meat, beans or fish.[60] Pythagoreans believed that a vegetarian diet fostered a healthy body and enhanced the search for Arete. The purpose of vegetarianism in Pythagoreanism was not self-denial; instead, it was regarded as conducive to the best in a human being. Pythagoreans advanced a grounded theory on the treatment of animals. They believed that any being that experienced pain or suffering should not have pain inflicted on it unnecessarily. Because it was not necessary to inflict pain on animals for humans to enjoy a healthy diet, they believed that animals should not be killed for the purpose of eating them. The Pythagoreans advanced the argument that unless an animal posed a threat to a human, it was not justifiable to kill an animal and that doing so would diminish the moral status of a human. By failing to show justice to the animal, humans diminish themselves.[54]

Pythagoreans believed that human beings were animals, but with an advanced intellect and therefore humans had to purify themselves through training. Through purification humans could join the psychic force that pervaded the cosmos. Pythagoreans reasoned that the logic of this argument could not be avoided by killing an animal painlessly. The Pythagoreans also thought that animals were sentient and minimally rational.

Late-Pythagorean philosophers were absorbed into the Platonic school of philosophy and in the 4th century BC the head of the

Female philosophers

The biographical tradition on Pythagoras holds that his mother, wife and daughters were part of his inner circle.[63] Women were given equal opportunity to study as Pythagoreans and learned practical domestic skills in addition to philosophy.[64]

Many of the surviving texts of women Pythagorean philosophers are part of a collection, known as pseudoepigrapha Pythagorica, which was compiled by Neopythagoreans in the 1st or 2nd century. Some surviving fragments of this collection are by early-Pythagorean women philosophers, while the bulk of surviving writings are from late-Pythagorean women philosophers who wrote in the 4th and 3rd century BC.[11] Female Pythagoreans are some of the first female philosophers from which texts have survived.

Scholars believe that

Influence on Plato and Aristotle

Pythagoras' teachings and Pythagoreanism influenced

Neopythagoreanism

The Neopythagoreans were a school and a religious community. The revival of Pythagoreanism has been attributed to

Neopythagoreans combined Pythagorean teachings with

Neopythagoreans manifested a strong interest in numerology and the superstitious aspects of Pythagoreanism. They combined this with the teachings of Plato's philosophic successors. Neopythagorean philosophers engaged in the common ancient practice of ascribing their doctrines to the designated founder of their philosophy and by crediting their doctrines to Pythagoras himself, they hoped to gain authority for their views.[67]

Later influence

On early Christianity

Early Christian theologians, such as

On numerology

1st century treatises of Philo and Nicomachus popularised the mystical and cosmological symbolism Pythagoreans attributed to numbers. This interest in Pythagorean views on the importance of numbers was sustained by mathematicians such as Theon of Smyrna, Anatolius and Iamblichus. These mathematicians relied on Plato's Timaeus as their source for Pythagorean philosophy.[78]

In the

The 11th-century Byzantine professor of philosophy

In the Jewish communities the development of the

On mathematics

Besides the enthusiasm that developed in the Latin and Byzantine worlds in the Middle Ages for Pythagorean numerology, the Pythagorean tradition of perfect numbers inspired profound scholarship in

In the Middle Ages

In the

Although the concept of the

In the early 6th century the Roman philosopher

Arabic translations of the Golden Verses were produced in the 11th and 12th centuries.

The four books of the Corpus Areopagiticum or

In the

On Western science

In the preface of

- At first I found in Heraclides of Pontus and Ecphantus the Pythagorean make the earth move, not in a progressive motion, but like a wheel in a rotation from west to east about its own center."[91][92][93]

In the 16th century

Many of the most eminent 17th century natural philosophers in Europe, including

At the height of the

The Pythagorean belief that all bodies are composed of numbers and that all properties and causes could be expressed in numbers, served as the basis for a mathematization of science. This mathematization of the physical reality climaxed in the 20th century. The pioneer of physics Werner Heisenberg argued that "this mode of observing nature, which led in part to a true dominion over natural forces and thus contributes decisively to the development of humanity, in an unforeseen manner vindicated the Pythagorean faith".[98]

See also

- Dyad (Greek philosophy)

- Esoteric cosmology

- Hippasus

- Ionian School (philosophy)

- Incommensurable magnitudes

- Ipse dixit

- Mathematical beauty

- Mathematicism

- Pyrrhonism

- Sacred geometry

- Tetractys

- Unit-point atomism

References

- ^ George, Calian Florin (2021). "Numbers, ontologically speaking: Plato on numerosity". Numbers and Numeracy in the Greek Polis. Brill. p. 219 ff.

- ISBN 0-486-22332-9.

- ^ a b Riedweg 2008, p. 26.

- ^ Riedweg 2008, p. 27.

- ^ Zhmud 2012, p. 29.

- ^ a b Zhmud 2012, p. 30.

- ^ a b c Zhmud 2012, p. 33.

- ^ a b Zhmud 2012, p. 38.

- ^ Zhmud 2012, p. 39.

- ^ Zhmud 2012, p. 44.

- ^ a b c Ballif & Moran 2005, p. 315.

- ^ Pomeroy 2013, p. xvi.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-313-32178-8.

- ^ Pomeroy 2013, p. 1.

- ^ a b c McKirahan 2011, p. 79.

- ISBN 978-1-4351-1400-5.

- ^ August Böckh (1819). Philolaos des Pythagoreers Lehren nebst den Bruchstücken seines Werkes. In der Vossischen Buchhandlung. p. 14.

Pythagoras Lehren nebst den Bruchstücken seines Werkes.

- ^ Huffman 2024.

- ^ Ball 1908, p. 28.

- ^ Huffman 2024.

- ^ McKirahan 2011, pp. 88–89.

- ^ a b Kahn 2001, p. 72.

- ^ Kahn 2001, pp. 73–74.

- ^ a b McKirahan 2011, p. 89.

- ^ McKirahan 2011, p. 91.

- ^ Kahn 2001, p. 21.

- ^ Kahn 2001, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Kahn 2001, p. 52.

- ^ Cornelli, McKirahan & Macris 2013, p. 174.

- ^ Cornelli, McKirahan & Macris 2013, p. 84.

- ^ Zhmud 2012, p. 415.

- ^ Vamvacas 2009, p. 64.

- ^ a b Vamvacas 2009, p. 65.

- ^ a b Long 1999, p. 84.

- ^ a b Vamvacas 2009, p. 72.

- ^ )

- ^ a b c Vamvacas 2009, p. 68.

- ^ a b Vamvacas 2009, p. 69.

- ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- ISBN 9780933999510.

- ^ Riedweg 2008, p. 30.

- ^ a b c Vamvacas 2009, p. 70.

- ^ Vamvacas 2009, p. 71.

- ^ "Table of opposites". Archived from the original on March 24, 2025.

- ^ Orr 1913.

- ^ a b c Huffman 2024.

- ^ a b c d Riedweg 2008, p. 84.

- ^ a b Riedweg 2008, p. 85.

- ^ Aristotle. "13". On the Heavens. Vol. II. Retrieved Apr 17, 2016.

- doi:10.1086/368583.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-60925-394-3.

- ISBN 978-1-58477-101-2.

- ISBN 978-1-904768-02-9.

- ^ a b c Campbell 2014, p. 539.

- ISBN 978-0-8028-3346-4.

- ISBN 978-0-8028-3346-4.

- ^ Kahn 2001, pp. 4, 11–12, 14; Zhmud 2012, p. 221.

- ^ Zhmud 2012, p. 232–33.

- ^ McKirahan 2011, p. 88.

- ^ See for instance the popular treatise by Antonio Cocchi, Del vitto pitagorico per uso della medicina, Firenze 1743, which initiated a debate on the "Pythagorean diet".

- ^ a b c Campbell 2014, p. 540.

- ^ Campbell 2014, p. 530.

- ^ Pomeroy 2013, p. 52.

- ISBN 978-0-8093-2137-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-313-32178-8.

- ^ a b Vamvacas 2009, p. 76.

- ^ a b McKirahan 2011, p. 80.

- ^ McKirahan 2011, p. 81.

- ^ ISBN 978-90-04-21732-4.

- ISBN 978-0-674-00261-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-136-61158-2.

- ^ Riedweg 2008, p. 73.

- ^ a b c Joost-Gaugier 2007, p. 118.

- ^ a b Joost-Gaugier 2007, p. 119

- ^ a b c Joost-Gaugier 2007, p. 117.

- ISBN 978-1-57647-117-3.

- ^ Riedweg 2008, p. 29; Kahn 2001, pp. 31–36.

- ^ a b Joost-Gaugier 2007, pp. 117–118.

- ^ a b c d Joost-Gaugier 2007, p. 120.

- ^ Joost-Gaugier 2007, p. 123.

- ^ Joost-Gaugier 2007, p. 125.

- ^ Zarepour, Mohammad Saleh (2022). "Arabic and Islamic Philosophy of Mathematics". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2022 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 2025-02-03.

- ^ Joost-Gaugier 2007, p. 124.

- ^ Joost-Gaugier 2007, p. 126.

- ^ Grafton, Most & Settis 2010, p. 798.

- ^ Joost-Gaugier 2007, pp. 121–122

- ^ Mancosu 2003, p. 599.

- ^ Kahn 2001, pp. 55–62.

- ISBN 978-0-7486-8815-9.

- ^ Cicero, Marcus Tullius (1885). The Academics of Cicero. Macmillan. p. 81.

- ^ "Pseudo-Plutarch, Placita Philosophorum, Book 3., chapter 13". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ISBN 978-1-349-01776-8.

- ^ Rosen 1978.

- ^ Mancosu 2003, p. 603.

- ^ Mancosu 2003, pp. 597–98.

- ^ Mancosu 2003, p. 604.

- ^ Mancosu 2003, p. 609.

- ^ a b Vamvacas 2009, p. 77.

Bibliography

- Ball, W W Rouse (1908). A short account of the history of mathematics (4th ed.). ) Reprinted by Dover Publications, Mineola, NY, 1960.

- Ballif, Michelle; Moran, Michael G., eds. (2005). Classical rhetorics and rhetoricians: critical studies and sources. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-313-32178-8.

- Campbell, Gordon Lindsay, ed. (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Animals in Classical Thought and Life. Oxford University Press. LCCN 2014941667.

- Cornelli, Gabriele; McKirahan, Richard D; Macris, Constantinos (2013). On Pythagoreanism. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-031850-0.

- Grafton, Anthony; Most, Glenn W; Settis, Salvatore, eds. (2010). The classical tradition. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. OCLC 318876873.

- Huffman, Carl (27 September 2024). "Philolaus". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2024 ed.). Retrieved 2025-02-03.

- Joost-Gaugier, Christiane L (2007). Measuring heaven: Pythagoras and his influence on thought and art in antiquity and the Middle Ages. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-7409-5.

- Kahn, Charles H (2001). Pythagoras and the Pythagoreans. Hackett Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60384-682-0.

- Long, A A, ed. (1999). The Cambridge Companion to Early Greek Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44667-9.

- McKirahan, Richard D (2011). Philosophy Before Socrates: An Introduction with Texts and Commentary (2nd ed.). Hackett Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60384-612-7.

- Park, Katherine; Daston, Lorraine, eds. (2003). Early modern science. Cambridge History of Science. Vol. 3. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57244-6.

- Mancosu, Paolo. "Acoustics and optics". In Park & Daston (2003), pp. 596–631.

- Orr, M A (1913). Dante and the early astronomers. London: Gall and Inglis – via Internet Archive.

- Pomeroy, Sarah B (2013). Pythagorean women: their history and writings. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-0956-6.

- Riedweg, Christoph (2008). Pythagoras: his life, teaching, and influence. Translated by Rendall, Steven. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-7452-1.

- Rosen, Edward (1978). "Aristarchus of Samos and Copernicus". Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists. 15 (1/2): 85–93. JSTOR 24518756.

- Vamvacas, Constantine J (2009) [First published 2001]. The founders of Western thought – the Presocratics: a diachronic parallelism between presocratic thought and philosophy and the natural sciences. Springer. LCCN 2009920271.

- Zhmud, Leonid (2012). Pythagoras and the early Pythagoreans. Translated by Windle, Kevin; Ireland, Rosh. Oxford University Press. OCLC 764348689.

External links

Media related to Pythagoreanism at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pythagoreanism at Wikimedia Commons- Carl Huffman. "Pythagoreanism/". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.