Robert Hues

Robert Hues | |

|---|---|

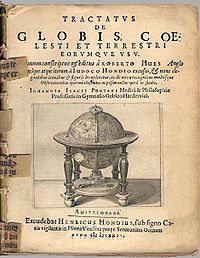

The title page of a 1634 version of Hues' Tractatus de globis in the collection of the Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal | |

| Born | 1553 Little Hereford, Herefordshire, England |

| Died | 24 May 1632 (aged 78–79) Oxford, Oxfordshire, England |

| Alma mater | St Mary Hall, Oxford (BA, 1578) |

| Known for | publishing Tractatus de globis et eorum usu (Treatise on Globes and their Use, 1594) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Mathematics, geography |

Robert Hues (1553 – 24 May 1632) was an English

In 1594, Hues published his discoveries in the Latin work Tractatus de globis et eorum usu (Treatise on Globes and Their Use) which was written to explain the use of the terrestrial and celestial globes that had been made and published by Emery Molyneux in late 1592 or early 1593, and to encourage English sailors to use practical astronomical navigation. Hues' work subsequently went into at least 12 other printings in Dutch, English, French and Latin.

Hues continued to have dealings with Raleigh in the 1590s, and later became a servant of Thomas Grey, 15th Baron Grey de Wilton. While Grey was imprisoned in the Tower of London for participating in the Bye Plot, Hues stayed with him. Following Grey's death in 1614, Hues attended upon Henry Percy, the 9th Earl of Northumberland, when he was confined in the Tower; one source states that Hues, Thomas Harriot and Walter Warner were Northumberland's constant companions and known as his "Three Magi", although this is disputed. Hues tutored Northumberland's son Algernon Percy (who was to become the 10th Earl of Northumberland) at Oxford, and subsequently (in 1622–1623) Algernon's younger brother Henry. In later years, Hues lived in Oxford where he was a fellow of the University, and discussed mathematics and related subjects with like-minded friends. He died on 24 May 1632 in the city and was buried in Christ Church Cathedral.

Early years and education

Robert Hues was born in 1553 at

Hues was a friend of the geographer Richard Hakluyt, who was then regent master of Christ Church. In the 1580s, Hakluyt introduced him to Walter Raleigh and explorers and navigators whom Raleigh knew. In addition, it is likely that Hues came to know astronomer and mathematician Thomas Harriot and Walter Warner at Thomas Allen's lectures in mathematics. The four men were later associated with Henry Percy, the 9th Earl of Northumberland,[1][8] who was known as the "Wizard Earl" for his interest in scientific and alchemical experiments and his library.[9]

Career

Hues became interested in geography and mathematics – an undated source indicates that he disputed accepted values of variations of the compass after making observations off the Newfoundland coast. He either went there on a fishing trip, or may have joined a 1585 voyage to Virginia arranged by Raleigh and led by Richard Grenville, which passed Newfoundland on the return journey to England. Hues perhaps become acquainted with the sailor Thomas Cavendish at this time, as both of them were taught by Harriot at Raleigh's school of navigation. An anonymous 17th-century manuscript states that Hues circumnavigated the world with Cavendish between 1586 and 1588 "purposely for taking the true Latitude of places";[11] he may have been the "NH" who wrote a brief account of the voyage that was published by Hakluyt in his 1589 work The Principall Navigations, Voiages, and Discoveries of the English Nation.[12] In the year that book appeared, Hues was with Edward Wright on the Earl of Cumberland's raiding expedition to the Azores to capture Spanish galleons.[1]

Beginning in August 1591, Hues joined Cavendish on another attempt to circumnavigate the globe. Sailing on the Leicester, they were accompanied by the explorer

During the voyage, Hues made

Tractatus de globis begins with a letter by Hues dedicated to Raleigh that recalled geographical discoveries made by Englishmen during Elizabeth I's reign. However, he felt that his countrymen would have surpassed the

In the 1590s, Hues continued to have dealings with Raleigh – he was one of the executors of Raleigh's will

In 1616, following Grey's death, Hues began to be "attendant upon th'aforesaid Earle of Northumberland for matters of learning",[30] and was paid a yearly sum of £40 to support his research until Northumberland's death in 1632.[1][15] Wood stated that Harriot, Hues and Warner were Northumberland's "constant companions, and were usually called the Earl of Northumberland's Three Magi. They had a table at the Earl's charge, and the Earl himself did constantly converse with them, and with Sir Walter Raleigh, then in the Tower".[31] Together with the scientist Nathanael Toporley and the mathematician Thomas Allen, the men kept abreast of developments in astronomy, mathematics, physiology and the physical sciences, and made important contributions in these areas.[32] According to the letter writer John Chamberlain, Northumberland refused a pardon offered to him in 1617, preferring to remain with Harriot, Hues and Warner.[33] However, the fact that these companions of Northumberland were his "Three Magi" studying with him in the Tower of London has been regarded as a romanticisation by the antiquarian John Aubrey and disputed for lack of evidence.[1][34] Hues was tutor to Northumberland's sons: first Algernon Percy, who subsequently became the 10th Earl of Northumberland, at Oxford where he matriculated at Christ Church in 1617; and later Algernon's younger brother Henry in 1622–1623. Hues lived at Christ Church at this time, but may have occasionally attended upon Northumberland at Petworth House in Petworth, West Sussex, and at Syon House in London after the latter's release from the Tower in 1622.[32] Hues sometimes met Walter Warner in London, and they are known to have discussed the reflection of bodies.[1]

Later life

In later years, Hues lived in Oxford where he discussed mathematics and allied subjects with like-minded friends.[1][35] Cormack states he was a fellow at the University.[18] Under the terms of the will of Thomas Harriot, who died on 2 July 1621, Hues and Warner were given the responsibility of helping Harriot's executor Nathaniel Torporley to prepare Harriot's mathematical papers for publication. Hues was also required to help price Harriot's books and other possessions for sale to the Bodleian Library.[1]

Hues, who did not marry, died on 24 May 1632 in Stone House,

Depositum viri literatissimi, morum ac religionis integerrimi, Roberti Husia, ob eruditionem omnigenem [sic: omnigenam?], Theologicam tum Historicam, tum Scholasticam, Philologicam, Philosophiam, præsertim vero Mathematicam (cujus insigne monumentum in typis reliquit) Primum Thomæ Candishio conjunctissimi, cujus in consortio, explorabundis [sic: explorabundus?] velis ambivit orbem: deinde Domino Baroni Gray; cui solator accessit in arca Londinensi. Quo defuncto, ad studia henrici Comitis Northumbriensis ibidem vocatus est, cujus filio instruendo cum aliquot annorum operam in hac Ecclesia dedisset et Academiae confinium locum valetudinariae senectuti commodum censuisset; in ædibus Johannis Smith, corpore exhaustus, sed animo vividus, expiravit die Maii 24, anno reparatae salutis 1632, aetatis suæ 79.[37] [Here lies a highly lettered man, of the highest moral and religious integrity, Robert Hues, on account of his erudition in all subjects, both Theology and History, and Rhetoric, Philology, and Philosophy, but especially Mathematics (of which a notable volume [i.e., his book] remains in print). He was most closely associated with Thomas Cavendish, in whose company he explored the world by sail; then with Lord Baron Gray, for whom he came as consoler in the Tower of London. When Gray died, he was summoned to study in the same place with Henry Earl of Northumberland, to teach his son, and when he had worked for some years in this Church [i.e., Christ Church Cathedral], and had decided that the place next to the School [i.e., Christ Church, Oxford] was suitable for his health in his old age, he breathed his last at the house of John Smith, his body exhausted, but with a lively spirit, on 24 May, in the year of our salvation 1632, at the age of 79.]

Works

- Hues, Robert (1594), Tractatus de globis et eorum usu: accommodatus iis qui Londini editi sunt anno 1593, sumptibus Gulielmi Sandersoni civis Londinensis, conscriptus à Roberto Hues [Treatise on Globes and their Use: Adapted to those which have been Published in London in the Year 1593, at the Expense of William Sanderson, a London Resident, Written by Robert Hues], London: In ædibus Thomæ Dawson [in the house of Thomas Dawson], octavo. The following reprints are referred to by Clements Markham in his introduction to the Hakluyt Society's 1889 reprint of the English version of Tractatus de globis at pp. xxxviii–xl:

- 2nd printing: Hues, Robert (1597), Tractaet Ofte Hendelinge van het gebruijck der Hemelscher ende Aertscher Globe. Gheaccommodeert naer die Bollen, die eerst ghesneden zijn in Enghelandt door Io. Hondium, Anno 1693 [sic: 1593] ende nu gants door den selven vernieut, met alle de nieuwe ontdeckinghen van Landen, tot den daghe van heden geschiet, ende daerenboven van voorgaende fauten verbetert. In't Latijn beschreven, door Robertum Hues, Mathematicum, nu in Nederduijtsch overgheset, ende met diveersche nieuwe verclaringhe ende figueren vermeerdert en verciert. Door I. Hondium [Treatise or Essays on the Use of the Celestial and Terrestrial Globes. Tailored for the Globes which were First Made in England by J. Hondius, in the Year 1693 [sic: 1593], and which have now been Completely Revised by Him, with All New Discoveries of Countries up to the Present Day, and furthermore with Previous Errors Corrected. Described in Latin by Robert Hues, Mathematician, and now Translated into Dutch, and Enhanced and Ornamented with Several New Explanations and Figures, by J. Hondius], translated by Hondium, Iudocum, Amsterdam: Cornelis Claesz, quarto.[38]

- 3rd printing: Hues, Robert (1611), Tractatus de globis coelesti et terrestri ac eorum usu, conscriptus a Roberto Hues, denuo auctior & emendatior editus [Treatise on Globes Celestial and Terrestrial and their Use, written by Robert Hues, Second Enlarged and Corrected Edition], Amsterdam: OCLC 187141964(in Latin), octavo. A reprint of the first edition of 1594.

- 4th printing: Hues, Robert (1613), Tractaut of te handebingen van het gebruych der hemelsike ende aertscher globe [Treatise or Essays on the Use of the Celestial and Terrestrial Globes], Amsterdam: [s.n.] (in Dutch), quarto.

- 5th printing: Hues, Robert (1613), Tractatvs de globis, coelesti et terrestri, ac eorvm vsu [Treatise on Globes, Celestial and Terrestrial, and their Use], Heidelberg: Typis [Printed by] Gotthardi Voegelini, OCLC 46414822 (in Latin). Contains the Index Geographicus. DeGolyer Collection in the History of Science and Technology (now History of Science Collections), University of Oklahoma.

- 6th printing: Hues, Robert (1617), Tractatvs de globis, coelesti et terrestri eorvmqve vsv. Primum conscriptus & editus a Roberto Hues. Anglo semelque atque iterum a Iudoco Hondio excusus, & nunc elegantibus iconibus & figuris locupletatus: ac de novo recognitus multisque observationibus oportunè illustratus as passim auctus opera ac studio Iohannis Isacii Pontani ... [Treatise on Globes, Celestial and Terrestrial, and their Use. First Written and Published by Robert Hues, Englishman, and in the First and Second Editions Drawn by Jodocus Hondius, and now Enlarged by Elegant Pictures and Drawings, and again Revised and Fittingly Illustrated by Many Observations, and throughout Enlarged by the Work and Effort of John Isaac Pontanus ...], Amsterdam: Excudebat [printed by] H[enricus] Hondius (in Latin), quarto.

- 7th printing: Hues, Robert (1618), Traicté des globes, et de leur usage, traduit du Latin de Robert Hues, et augmente de plusieurs nottes et operations du compas de proportion par D Henrion, mathematicien [A Treatise on Globes and their Use, Translated from the Latin version by Robert Hues, and Augmented with Several Notes and Operations of the Compass of Proportion by D Henrion, Mathematician], translated by

- 9th printing: Hues, Robert (1627), Tractatvs de globis, coelesti et terrestri, ac eorvm vsv [Treatise on Globes, Celestial and Terrestrial, and their Use], Francofvrti ad Moenvm [Frankfurt am Main, Germany]: Typis & sumptibus VVechelianorum, apud Danielem & Dauidem Aubrios & Clementem Schleichium [Printed and paid for by the Wechelians, by Daniel and David Aubrios and Clement Schleich], duodecimo.

- 10th printing: Hues, Robert (1638), A Learned Treatise of Globes, both Cœlestiall and Terrestriall: With their Severall Uses. Written first in Latine, by Mr Robert Hues: And by him so Published. Afterward Illustrated with Notes, by Io. Isa. Pontanus. And now Lastly made English, for the Benefit of the Unlearned by John Chilmead MrA of Christ-Church in Oxon, London: Printed by the assigne of T[homas] P[urfoot] for P[hilemon] Stephens and C[hristopher] Meredith, and are to be sold at their shop at the Golden Lion in Pauls-Church-yard,

- 11th printing: A Latin version by Jodocus Hondius and John Isaac Pontanus appeared in London in 1659. Octavo.[42]

- 12th printing: Hues, Robert; John Isaac Pontanus (1659), A Learned Treatise of Globes, both Cœlestiall and Terrestriall with their Several Uses .., London: Printed by J.S. for Andrew Kemb, and are to be sold at his shop ..., OCLC 11947725, octavo. Collection of Yale University Library.

- 13th printing: Hues, Robert (1663), Tractatus de globis coelesti et terrestri eorumque usu ac de novo recognitus multisq[ue] observationibus opportunè illustratus ac passim auctus, opera et studio Johannis Isacii Pontani ...; adjicitur Breviarium totius orbis terrarum Petri Bertii ... [Treatise on Globes Celestial and Terrestrial and their Use, Collected Anew and Suitably Illustrated with Many Observations and Enlarged Throughout, by the Effort and Devotion of John Isaac Pontanus ... A Brief Account of the Whole Globe is Added by Peter Bertius ...], Oxford: Excudebat [printed by] W.H., impensis [at the expense of] Ed. Forrest, OCLC 13197923(in Latin).

- 2nd printing: Hues, Robert (1597), Tractaet Ofte Hendelinge van het gebruijck der Hemelscher ende Aertscher Globe. Gheaccommodeert naer die Bollen, die eerst ghesneden zijn in Enghelandt door Io. Hondium, Anno 1693 [sic: 1593] ende nu gants door den selven vernieut, met alle de nieuwe ontdeckinghen van Landen, tot den daghe van heden geschiet, ende daerenboven van voorgaende fauten verbetert. In't Latijn beschreven, door Robertum Hues, Mathematicum, nu in Nederduijtsch overgheset, ende met diveersche nieuwe verclaringhe ende figueren vermeerdert en verciert. Door I. Hondium [Treatise or Essays on the Use of the Celestial and Terrestrial Globes. Tailored for the Globes which were First Made in England by J. Hondius, in the Year 1693 [sic: 1593], and which have now been Completely Revised by Him, with All New Discoveries of Countries up to the Present Day, and furthermore with Previous Errors Corrected. Described in Latin by Robert Hues, Mathematician, and now Translated into Dutch, and Enhanced and Ornamented with Several New Explanations and Figures, by J. Hondius], translated by Hondium, Iudocum, Amsterdam: Cornelis Claesz,

- The Hakluyt Society's reprint of the English version was itself published as:

- Hues, Robert (1889), OCLC 149869781.

- Hues, Robert (1889),

The following works also are, or appear to be, versions of Tractatus de globis et eorum usu, though they are not mentioned by Markham:

- Hues, Robert (1623),

- Hues, Robert (1624), Tractatvs de globis, coelesti et terrestri eorvmqve vsv [Treatise on Globes, Celestial and Terrestrial, and their Use], Amsterdam: Excudebat [Printed by] H[enricus] Hondius, OCLC 8909075(in Latin).

- Hues, Robert (1627), Tractatus duo mathematici: Quorum primus de globis coelesti et terrestri, eorum usu [Two Mathematical Treatises: Of which the First One is about the Celestial and Terrestial Globes, and their Use], Frankfurt: Bryana, OCLC 179907636.

- Hues, Robert; Nottnagel, Christoph (1627), Tractatus duo quorum primus de globis coelesti et terrestri, eorum usu, à Roberto Hues, Anglo, conscriptus. Alter breviarium totius orbis Terrarum, Petri Bertii. Nunc primum luci commißi [Two Treatises of which the First One is about the Celestial and Terrestrial Globes, and their Use, signed by Robert Hues, Englishman. The Other One is an Anthology of Countries of the Whole World, by Peter Bertius. Now for the first time here gathered.] (3rd ed.), Wittenberg: [s.n.], OCLC 257661113.

- Hues, Robert (1634), Tractatvs de Globis Coelesti et Terrestri eorvmqve vsv: Primum conscriptus & editus à Roberto Hues Anglo semelque atque iteram à Iudoco Hondio excusus, & nunc elegantibus iconibus & figuris locupletatus: ac de novo recognitus multisque observationibus oportunè illustratus ac passim auctus opera ac studio. Iohannis Isacii Pontani Medici & Philosophiæ Professoris in Gymnasio Gelrico Hardervici [Treatise on Globes, Celestial and Terrestrial, and their Use. First Written and Published by Robert Hues, Englishman, and in the First and Second Editions Drawn by Jodocus Hondius, and now Enlarged by Elegant Pictures and Drawings, and again Revised and Fittingly Illustrated by Many Observations, and throughout Enlarged by the Work and Effort of John Isaac Pontanus, Physician and Professor of Philosophy of the School in Harderwijk], Amsterdam: Excudebat Henricus Hondius, sub signo Canis Vigilantis in Platea Vitulina prope Senatorium [Printed by Henricus Hondius, under the sign of the Watchful Dog in Calf Street [Kalverstraat] near the council hall].[44] Collection of the Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal.

- Hues, Robert (1651), Tractatus duo mathematici. Quorum primus de globis coelesti et terrestri, eorum usu, a Roberto Hues ... conscriptus. Alter breviarium totius orbis terrarum, Petri Bertii ... Editio prioribus auctior & emendatior [Two Mathematical Treatises. Of which the First One is about the Celestial and Terrestial Globes, and their Use, signed ... Robert Hues. The Other One an Anthology of Countries of the Whole World, of Peter Bertius ... First enlarged & improved edition], Oxford: Excudebat [Printed by] L. Lichfield, impensis [at the expense of] Ed. Forrest, OCLC 14913709, two pts. Collection of the Bodleian Library.

Notes

- ^ doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14045. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- OCLC 222963720

- fellowsof the University in exchange for free accommodation and some meals, and exemption from paying fees for lectures.

- OCLC 5574505, vols. 1–2. Hues is listed under the name "Hughes".

- OCLC 216610936

- ISBN 978-0-521-83187-1

- ^ a b Markham, "Introduction", Tractatus de globis, p. xxxv.

- OCLC 531838

- ^ David Singmaster (28 February 2003), BSHM Gazetteer: Petworth, West Sussex, British Society for the History of Mathematics, archived from the original on 25 May 2009, retrieved 7 February 2008. See also David Singmaster (28 February 2003), BSHM Gazetteer: Thomas Harriot, British Society for the History of Mathematics, archived from the original on 25 May 2009, retrieved 7 February 2008

- OCLC 6672789

- ^ MS Rawl. B 158, Bodleian Library, Oxford.

- OCLC 77435498

- ^ Margaret Montgomery Larnder (2000), "Davis (Davys), John", Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, archived from the original on 8 June 2009, retrieved 9 June 2009

- ISBN 978-1-57958-425-2

- ^ a b c d Markham, "Introduction", Tractatus de globis, p. xxxvi.

- ).

- JSTOR 1791852

- ^ S2CID 145588853

- doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/50911. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- ^ Markham, "Introduction", Tractatus de globis, pp. xxxviii–xl.

- The Huntington Library) in San Marino, California. Accidence is the branch of grammar that deals with the accidents or inflections of words. The term came to mean a book about the rudiments of grammar, and was extended to the rudiments or first principles of any subject: see "accidence2", OED Online (2nd ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989, retrieved 23 July 2016

- S2CID 178295770

- ^ Markham, "Introduction", Tractatus de globis, p. xli.

- ^ Markham, "Introduction", Tractatus de globis, pp. xli–xlii.

- ^ Markham, "Introduction", Tractatus de globis, pp. xlii–xliii.

- ^ a b Markham, "Introduction", Tractatus de globis, p. xlii.

- ^ Markham, "Introduction", Tractatus de globis, pp. xlii and xlvi.

- S2CID 164132753

- ISBN 978-0-8018-7397-3

- ISBN 978-0-19-822901-8

- OCLC 8166998, archived from the originalon 16 July 2011, retrieved 10 November 2008

- ^ a b Kargon, "The Wizard Earl and the New Science" in Atomism in England, pp. 5–17 at 16.

- OCLC 221477966: see Kargon, "The Wizard Earl and the New Science" in Atomism in England, pp. 5–17 at 16.

- Bibcode:1995QJRAS..36...97C

- ISBN 978-0-521-25133-4

- OCLC 84810015. See Markham, "Introduction", Tractatus de globis, p. xxxvii, n. 1.

- ^ Historia et antiquitates universitatis Oxoniensis, vol. 2, p. 534. The brass is also referred to at p. 288: "In laminâ œneâ, eidem pariati [sic: parieti?] impactâ talem cernis inscriptionem" (On the copper plate, driven to the same wall, one sees such an inscription). See Markham, "Introduction", Tractatus de globis, p. xxxvii, n. 1.

- OCLC 42811612). According to Markham, "Introduction", Tractatus de globis, pp. xxxvii–xxxviii, the title of this version is Tractaut of te handebingen van het gebruych der hemel siker ende aertscher globe, and it was printed in Antwerp.

- ^ J.J. O'Connor; E.F. Robertson (August 2006), Pierre Hérigone, The MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, archived from the original on 31 October 2007, retrieved 7 November 2008

- OCLC 8909075) suggests that the 1624 version was in Latin, not Dutch.

- OL 7015375M, retrieved 10 November 2008. According to Markham, "Introduction", Tractatus de globis, p. xxxix, although the title page of the work states that the translator was "John Chilmead", this is generally believed to be an error as no such person was known to have lived at the time. Instead, the translator is believed to be Edmund Chilmead (1610–1653), a translator, man of letters and music teacher who graduated in 1628 and was a chaplain of Christ Church, Oxford.

- ^ Markham, "Introduction", Tractatus de globis, pp. xxxix–xl.

- Museum of the History of Science, Oxford, 7 August 1995, archived from the originalon 2 May 2008, retrieved 11 November 2008

- ^ HUES, Robert, 1553–1632. Tractatvs de globis coelesti et terrestri eorvmqve vsv, Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal, 2002, archived from the original on 9 June 2011, retrieved 11 November 2008

References

- Kargon, Robert Hugh (1966), Atomism in England from Hariot to Newton, Oxford: OCLC 531838, chs. 2–4.

- ISBN 978-0-8337-1759-7.

- Maxwell, Susan M.; Harrison, B. (January 2008). "Hues, Robert (1553–1632)". doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14045. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.).

- Shirley, John W[illiam] (1983), "Thomas Harriot: A Biography", Journal for the History of Astronomy, 17, Oxford: S2CID 125341236.

Further reading

- Articles

- J.O.M. (1851), "Robert Hues on the Use of Globes", Notes and Queries, s1-IV: 384, archived from the original on 15 April 2013.

- Books

- Hutchinson, John (1890), Herefordshire Biographies, being a Record of such of Natives of the County as have Attained to more than Local Celebrity, with Notices of their Lives and Bibliographical References, together with an Appendix containing Notices of some other Celebrities, Intimately Connected with the County but not Natives of it, Hereford: Jakeman & Carver, OCLC 62357054.