Rocky Mountain Airways Flight 217

de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter 300 | |

| Operator | Rocky Mountain Airways |

|---|---|

| IATA flight No. | JC217 |

| ICAO flight No. | RMA217 |

| Call sign | ROCKY MOUNTAIN 217 |

| Registration | N25RM |

| Flight origin | Steamboat Springs Airport, Colorado, United States |

| Destination | Stapleton International Airport, Colorado, United States |

| Occupants | 22 |

| Passengers | 20 |

| Crew | 2 |

| Fatalities | 2 |

| Injuries | 20 |

| Survivors | 20 |

Rocky Mountain Airways Flight 217, referred to in the media as the "Miracle on Buffalo Pass",

Aircraft

The aircraft involved in the accident was a 5-year-old

Crew and passengers

The DHC-6 was carrying 22 occupants, 2

Flight

Rocky Mountain Airways Flight 217 was intended to depart

Captain Klopfenstein planned a flight plan using instrument flight rules (IFR) between Steamboat Springs Airport and the Gill VOR along the V101 airway at 17,000 ft (5,200 m)[b] and from Gill, proceed with visual flight rules (VFR) to Denver.[3]: 2

Accident

Flight 217 departed from Steamboat Springs at 18:55, two hours and ten minutes behind schedule, and was cleared to climb to its assigned altitude of 17,000 ft (5,200 m). First Officer Coleman, who was in command of the flight, flew the aircraft following the published departure for the airport, reversed course at 10,000 ft (3,000 m), crossed the non-directional beacon (NDB) over Steamboat Springs Airport at 12,000 ft (3,700 m), and intercepted the V101 airway flying east.[3]: 3 The aircraft encountered minor freezing precipitation and entered a cloud bank as it was climbing over Buffalo Pass. The Twin Otter encountered severe icing conditions on the aircraft's propellers and windshield, but the aircraft's deicing systems was able to remove the ice. The flight was able to climb up to 13,000 ft (4,000 m), but neither the first officer nor the captain was able to make the aircraft climb to a higher altitude at the normal engine power settings. Due the aircraft's inability to reach an altitude above 13,000 ft (4,000 m) before the Kater intersection, a point at the intersection of two radials, the captain elected to return to Steamboat Springs at 19:14, without informing the passengers.[3]: 3, 5 [6]

Flight 217 transmitted to Denver Center, the

Passenger efforts and rescue

All 22 people on board survived the initial impact. 14 passengers and both crew members were seriously injured, with the majority of them suffering fractured

Despite the aircraft being severely damaged in the crash, the cabin lights remained on for 4 to 5 hours after the crash, which was ruled to be a significant reason for passenger survival.[3]: 17–18 [7] One of the slightly injured passengers was a 20-year-old male who had extensive winter survival training. He and another male passenger were able to exit the cabin and obtain warm clothing, which was distributed to the most injured passengers. Despite the efforts of the least injured passengers, a 26-year-old female, one of the USFS employees on the flight, died of her injuries approximately 4 hours after the crash.[3]: 15–18 [6]

In the cockpit, both Captain Klopfenstein and First Officer Coleman were severely injured and were trapped in their seats in the snow. The same passenger who had winter survival training attempted to remove the snow around the first officer but was unsuccessful due to the violent winds. He and another passenger built a shelter around the first officer with suitcases.[3]: 18 [6]

During the crash, one of the

Investigation

The investigation was conducted by the

Effects of icing

In a post-accident interview, First Officer Coleman told the NTSB that the aircraft's deicing and anti-icing systems were functioning properly during the flight. Evidence in the wreckage supported this, with the

Effects of mountain waves

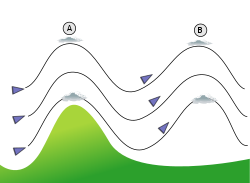

The route of the accident flight went over the

Certification data the NTSB acquired showed that under the icing conditions the flight encountered, the crew should have been able to maintain an altitude of 19,500 ft (5,900 m). But since the aircraft was not able to climb above 13,000 ft (4,000 m) before its diversion, the NTSB concluded that the downdrafts associated with the mountain waves in the area combined with the icing conditions on the flight was beyond the aircraft's ability to maintain flight.[3]: 25

Captain's decision to conduct the flight

The NTSB highlighted Captain Klopfenstein's decision to conduct the flight and the flight's attempted return to Steamboat Springs. The captain's decision to return to his origin airport was prompted by the aircraft's inability to climb above 13,000 ft (4,000 m) before the Kater Intersection.

Captain Klopfenstein's decision to depart Steamboat Springs in the first place was ruled as an even larger factor in the accident. The captain was aware of the severe weather conditions that he would later experience on the flight. Earlier on December 4, he and First Officer Coleman attempted to fly Flight 212 to Steamboat Springs via Granby. Due to strong winds en route, the flight was unable to climb high enough, and the flight had to return to Denver. Later, on Flight 216, they encountered strong headwinds and heavy icing on the descent into Steamboat Springs.[3]: 25

Company procedure at Rocky Mountain Airways prohibited flight into "known or forecast heavy icing conditions...unless the captain has good reason to believe that the weather conditions as forecast will not be encountered due to change or later observed conditions." The NTSB stated that the captain, who had considerable experience in mountain flying conditions, believed that the calm conditions on Flight 216 would allow for a smooth flight to Denver. He was likely unaware of the strong winds in the area as during Flight 216's descent, the severe icing likely masked the simultaneous performance degradation the winds brought. Additionally, the weather conditions at Steamboat Springs were calm and did not correlate with mountain wave conditions, and the meteorological information provided to him made no mention of such conditions.[3]: 26

In regard to Captain's Klopfenstein's decision to fly, the NTSB concluded that he was not aware of the presence of the mountain wave(s) en route. Evidence showed that signals that showed mountain wave conditions were obscured by other weather conditions that were already on the captain's mind. This led to a false attitude of safety, where the captain believed that he could fly to Denver even if it was against company guidance.[3]: 27

Final report

In their final report, the NTSB concluded the probable cause of the accident was:

Severe icing and strong downdrafts associated with a mountain wave which combined to exceed the aircraft's capability to maintain flight. Contributing to the accident was the captain's decision to fly into probable icing conditions that exceeded the conditions authorized by company directive.[3]: 30 [12]

They recommended that crew members who fly for commuter airlines in mountainous areas should have survival training, and mandatory installation for shoulder harnesses in flight crew seats on

Aftermath

The departure procedure for Steamboat Springs was changed to allow aircraft to gain more altitude flying westward before turning east over the mountains.[8]

In 2009, a memorial to the crash was unveiled at the Wings Over the Rockies Air and Space Museum by First Officer Coleman, many of the surviving 19 passengers, and several of the rescuers.[5]

See also

- Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571 (1972) – Crashed in the Andes, 72-day survival

- Trans-Colorado Airlines Flight 2286 (1988) – Crashed in snowy conditions in Southern Colorado

- Varig Flight 254 (1989) – Forced landing in the Amazon rainforest, 4-day survival

- Mount Denain mountain wave conditions

Notes

References

- ^ Heffel, Nathan (December 19, 2017). "Miracle on Buffalo Pass Remembered Nearly 40 Years After Plane Crash". Colorado Public Radio. Retrieved October 13, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Shapiro, Gary (September 30, 2018). "Hope on Buffalo Pass: The incredible rescue of flight 217". 9News. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Aircraft Accident Report: Rocky Mountain Airways, Inc. deHavilland DHC-6 Twin Otter, N25RM, near Steamboat Springs, Colorado, December 4, 1978 (PDF) (Report). National Transportation Safety Board. May 3, 1979. NTSB-AAR-79-6. Retrieved October 5, 2024.

- ^ "Crash of a De Havilland DHC-6 Twin Otter in Steamboat Springs: 2 killed". Bureau of Aircraft Accident Archives. Retrieved October 6, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Pankratz, Howard (March 5, 2009). "1978 plane crash recalled in new exhibit". The Denver Post. Retrieved October 9, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f Hohl, Frances. "Buff Pass plane crash survivor, rescuer share 'miracle' stories". Steamboat Pilot. Retrieved October 9, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Katz, Peter (January 7, 2019). "After the Accident: Twin Otter Crash In The Rockies From 40 Years Ago". planeandpilotmag.com.

- ^ a b Terell, Blythe (June 8, 2008). "Infant who survived 1978 plane crash on Buffalo Pass now soars above Yampa Valley himself". Steamboat Pilot. Retrieved October 11, 2024.

- ^ Bowden, Dean T. (February 1, 1956). "Effect of Pneumatic De-icers and Ice Formations on Aerodynamic Characteristics of a Airfoil" (PDF). National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. Retrieved October 12, 2024.

- ^ "Park Range". peakbagger.com. Retrieved October 12, 2024.

- ^ "Mountain Waves". SkyBrary. Retrieved October 12, 2024.

- ^ Ranter, Harro. "Accident de Havilland Canada DHC-6 Twin Otter 300 N25RM, Monday 4 December 1978". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved October 12, 2024.