Sängerfest

Sängerfest, also Sängerbund-Fest, Sängerfeste, or Saengerfest, meaning singer festival, is a competition of Sängerbunds, or singer groups, with prizes for the best group or groups. Such public events are also known as a Liederfest, or song festival. Participants number in the hundreds and thousands, and the fest is usually accompanied by a parade and other celebratory events. The sängerfest is most associated with the Germanic culture. Its origins can be traced back to 19th century Europe. Swiss composer Hans Georg Nägeli and educator Carl Friedrich Zelter, both protégés of Swiss educator Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, established sängerbunds to help foster social change throughout Germany and Prussia. University students began to choose the art form as an avenue for political statements. As the sängerfest concept gained popularity and spread around the world, it was adapted by Christian churches for spiritual worship services. European immigrants brought the tradition in a non-political form to the North American continent. In the early part of the 20th century, sängerfest celebrations drew devotees in the tens of thousands, and included some United States presidents among their audiences. Sängerbunds are still active in Europe and in American communities with Germanic heritage.

History

Europe

Students of Swiss educator Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, a proponent of social reform, applied his teachings when founding some singing groups as an instrument for cultural change.[1] One of his students was Carl Friedrich Zelter, who helped establish the sängerbund movement throughout Prussia in 1809.[2] Pestalozzi's protégé Hans Georg Nägeli was a composer, music teacher and songbook publisher[3] who made numerous journeys across Germany from 1819 to encourage the formation of male singing groups for social reform.[4] Nägeli established several sängerbunds in Switzerland, which became the inspiration for the 1824 establishment of the Stuttgarter Liederkranz.[5][6] Following the 1819 Carlsbad Decrees in Germany, male-only choral celebrations with hundreds or thousands of vocalists were popular with the masses and often part of political events.[7]

Composer

Christian church organizations known as Christlicher sängerbunds adapted the sängerfest for religious gatherings and helped spread its popularity throughout Europe, North America and Australia.

North America

Mennonites established the northwest

In 1838, the Cincinnati Deutscher Gesangverein was formed in

The first sängerfest in Texas was held in 1853 in

22nd and 24th President Grover Cleveland, his wife, and guests took a special train from Washington, D.C. on "Independence Day", 4 July 1888, forty miles northeast to see a Baltimore event. Cleveland had friends who were members of the sängerbunds.[38] 27th President William Howard Taft attended the 1 July 1912 event in Philadelphia.[39] On 15 June 1903, 26th President Theodore Roosevelt and Ambassador Herman Speck von Sternberg[40] attended a sängerfest of 6,000 individual singers at Baltimore's Armory Hall. All 9,000 seats were sold out. President Roosevelt delivered an address praising the German culture and the sängerfest tradition.[41][42] The Northeastern Sängerbund presented selections by composers Herman Spielter, David Melamet, Carl Friedrich Zöllner, E.S. Engelsberg, Felix Mendelssohn and Richard Wagner.[43]

When

Germans began emigrating to Canada through

In 1916 at his sentencing for bigamy, Count Max Lymer Louden related another misdeed from his past. Louden claimed he had been hired by a group of wealthy German Americans with a secret fund of $16,000,000 to take 150,000 German reservists, disguised as sängerbunds, across the

Current events

Although some local festivals were canceled or suspended during the two world wars owing to rising anti-German sentiment, the triennial Sängerfest tradition has largely survived and many communities in areas with a significant German-American population have Sängerfests today.

Two major German-American singing associations are the Nordöstlicher (North Eastern) Sängerbund and the much larger Nord-Amerikanischer (North American) Sängerbund.

- Nordöstlicher Sängerbund: The 49th Sängerfest was in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in 2006. The 50th Sängerfest, hosted by the Washington Sängerbund, took place on the 2009 Memorial Day Weekend in Washington, D.C.[52] The 51st Sängerfest, hosted by the Lehigh Sängerbund, took place in June 2012 in Allentown, Pennsylvania. The Bloomfield Liedertafel hosted the 52nd Sängerfest in 2015 in Pittsburgh, PA.

- Nord-Amerikanischer Sängerbund: The 61st Sängerfest of the Nord-Amerikanischer Sängerbund was June 2013 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin with over 1300 singers. The 62nd Sängerfest took place May 27–29, 2016 in Pittsburgh, PA.

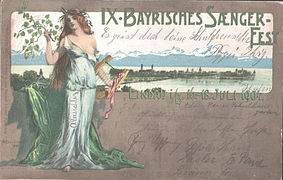

Gallery

-

Medaille - Deutsches Sängerbundesfest in Wien 1890 - von A. Scharff

-

Medaille - Deutsches Sängerbundesfest in Wien 1890 - von J. Schwerdtner

See also

- Saengerfest Halle

- Saengerfest Park

Notes

- ^ Mark 2008, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Applegate 2005, p. 155.

- ^ Smither 2000, p. 30.

- ^ Lorenzkowski 2010, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Harrison, Welch & Adler 2012, p. 245.

- ^ Garatt 2010, p. 98, An Equal Music? Singing Festivals as Mass and Counter-culture.

- ^ Freitag & Wende 2001, p. 270.

- ^ Palmer 2004, p. 104.

- ^ Stokes & Bostridge 2011, ebook.

- ^ Garatt 2010, p. 118, An Equal Music? Singing Festivals as Mass and Counter-culture.

- ^ Eichener 2012, p. 277.

- ^ Garatt 2010, pp. 118–119, An Equal Music? Singing Festivals as Mass and Counter-culture.

- ^ "The German Unions". The New York Times. 26 June 1855. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ Huebert 1999, p. 68.

- ^ Huebert 1999, pp. 68, 73.

- ^ Huebert 1999, pp. 68–70.

- ^ Toews 1995, p. 230.

- ^ Adam 2005, pp. 443–445.

- ^ Faust 1909, pp. 271–276, VI, Social and Cultural Influences of the German Element, I. Music and the Fine Arts.

- ^ a b "History of Nord-Amerikanischer Sängerbund". Nord-Amerikanischer Sängerbund. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- ^ "Musician Societies of Brooklyn". Brooklyn Daily Eagle Almanac. 1891. pp. 95–97.

- ^ "The Pan American Exposition at Buffalo N.Y.". The Cambrian, Volume 21. Thomas J. Griffiths. 1901. p. 14.

- ^ Goss 1912, p. 465.

- ^ a b Osborne 2004, p. 344, The German Singing Societies.

- ^ Greve 1904, p. 922.

- ^ McIntosh & Hobart 1908, Heinrich Gebhard.

- ^ Studer 2010, pp. 86–91, The Saengerbund Festival.

- ^ Heide, Jean M. "Beethoven Männerchor". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ a b Albrecht, Theodore. "German Music". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ Warner, Harry T (1913). "The Twenty-Ninth Biennial State Saengerfest". Texas Magazine. 7: 549–550. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ a b Wolz & Specht 2005, pp. 119–137, Roots of Classical Music in Texas-The German Contribution.

- ^ Albrecht, Theodore. "Texas State Sängerbund". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ Kelley & Snell 2004, p. 17.

- ^ "History of the Founding of the Beethoven Maennerchor". Beethoven Maennerchor. Retrieved 10 December 2010.

- ^ "Houston Sängerbund". Houston Sängerbund. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ^ Grob, Julie. "Houston Saengerbund Records, 1874–1985". University of Houston Libraries. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- ^ Kirkland 2009, p. 161.

- ^ "The National Sängerfest" (PDF). The New York Times. 4 July 1888. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ "Taft to Attend Saengerfest on July 1". New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ Watts 2003, p. 233.

- ^ Straus 1913, p. 312.

- ^ "Saengerfest address 15 June 1903". Almanac of Theodore Roosevelt. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ "President a Guest at Monster Saengerfest" (PDF). The New York Times. 16 June 1903. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ Siegel 1995, pp. 22–24.

- ^ "Saengerfest Concert Draws a Crowd of 25,000" (PDF). The New York Times. 2 July 1906. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ "Lunenburg". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica-Dominion. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- ^ "The German Saengerfest in Canada" (PDF). The New York Times. 19 August 1875. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ Kallmann & Kemp 2006.

- ^ "Mennonites". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica-Dominion. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- ^ "Louden Tells Plot to Invade Canada" (PDF). The New York Times. 28 April 1916. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ^ Crump 2010, pp. 145–146, The Phantom Invasion.

- ^ "The Lyre, the Symbol for Singing". Nordöstlicher Sängerbund of America. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

References

- Adam, Thomas (2005). Germany and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History (Transatlantic Relations). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-628-2.

- Applegate, Celia (2005). Bach in Berlin: Nation and Culture in Mendelssohns Revival of the St. Matthew Passion. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4389-3.

- Crump, Jennifer (2010). Canada Under Attack. Toronto, Canada: Dundurn Group. ISBN 9781554887316.

- Eichener, Barbara (2012). History in Mighty Sounds: Musical Constructions of German National Identity, 1848–1914 (Music in Society and Culture). Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-754-1.

- Faust, Albert Bernhardt (1909). The German Element in the United States With Special Reference to Its Political, Moral, Social, and Educational Influence, Vol II. New York, NY: Houghton Mifflin Company. OCLC 832230796.

- Freitag, Sabine; Wende, Peter (2001). British Envoys to Germany 1816–1866: Volume 1, 1816–1829. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79066-6.

- Garatt, James (2010). Music, Culture and Social Reform in the Age of Wagner. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-11054-9.

- Goss, Charles Frederic (1912). Cincinnati, the Queen City, 1788–1912. Cincinnati, OH: S.J. Clarke Publishing Company. OCLC 1068766.

- Greve, Charles Theodore (1904). Centennial History of Cincinnati and Representative Citizens. Chicago, IL: Biographical Pub. Co. OCLC 3355988.

- Harrison, Scott D.; Welch, Graham F.; Adler, Adam (2012). Perspectives on Males and Singing (Landscapes: the Arts, Aesthetics, and Education). New York, NY: Springer. ISBN 978-94-007-2659-8.

- Huebert, Helmut (1999). Events and People: Events in Russian Mennonite History and the People That Made Them Happen. Winnipeg, Canada: Springfield Publishers. ISBN 978-0-920643-06-8.

- Kallmann, Helmut; Kemp, Walter P. (7 February 2006). "Sängerfeste". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- Kelley, Bruce; Snell, Mark A (2004). Bugle Resounding: Music and Musicians of the Civil War Era. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri. ISBN 978-0-8262-1538-3.

- Kirkland, Kate Saven (2009). ISBN 978-0-292-71865-4.

- Lorenzkowski, Barbara (2010). Sounds of Ethnicity: Listening to German North America, 1850–1914. Winnipeg, Canada: University of Manitoba Press. ISBN 978-0-88755-301-1.

- Mark, Michael (2008). A Concise History of American Music Education. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education. ISBN 9781578868506.

- McIntosh, Burr William; Hobart, Clark (1908), The Burr McIntosh monthly, Volume 17, New York, NY: The Burr Publishing Company

- Osborne, William (2004). Music in Ohio. Kent, OH: Kent State Univ Press. ISBN 978-0-87338-775-0.

- Palmer, William (2004). Blood and Village: Two Lives, 1897–1991. Philadelphia, PA: Xlibris Corp. ]

- Siegel, Alan A (1995). Smile: A Picture History of Olympic Park, 1887–1965. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 978-0-8135-2255-5.

- Stokes, Richard; Bostridge, Ian (2011). The Book of Lieder. London, UK: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-26091-1.

- Smither, Howard E (2000). A History of the Oratorio: Vol. 4: The Oratorio in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-2511-2.

- Straus, Oscar Solomon (1913). The American Spirit. New York, NY: The Century Company. OCLC 675513.

- Studer, Jacob Henry (2010). Columbus, Ohio, Its History, Resources, and Progress. Columbus, OH: BiblioBazaar. ISBN 978-1-140-32066-1.

- Toews, Paul (1995). Bridging Troubled Waters: Mennonite Brethren at Mid-Twentieth Century. Winnipeg, Canada: Kindred Productions. ISBN 978-0-921788-23-2.

- Watts, Susan (2003). Rough Rider in the White House: Theodore Roosevelt and the Politics of Desire. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-87607-8.

- Wolz, Larry; Specht, Joe W. (2005). The Roots of Texas Music. College Station, TX: TAMU Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-492-2.

Further reading

- Greene, Victor R (2004). A Singing Ambivalence: American Immigrants Between Old World and New, 1830–1930. Kent State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87338-794-1.