Einstein field equations: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 343: | Line 343: | ||

*[http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8MWNs7Wfk84&feature=PlayList&p=858478F1EC364A2C&index=2 Video Lecture on Einstein's Field Equations] by [[MIT]] Physics Professor Edmund Bertschinger. |

*[http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8MWNs7Wfk84&feature=PlayList&p=858478F1EC364A2C&index=2 Video Lecture on Einstein's Field Equations] by [[MIT]] Physics Professor Edmund Bertschinger. |

||

*[http://scitation.aip.org/content/aip/magazine/physicstoday/article/68/11/10.1063/PT.3.2979 Arch and scaffold: How Einstein found his field equations] Physics Today November 2015, History of the Development of the Field Equations |

*[http://scitation.aip.org/content/aip/magazine/physicstoday/article/68/11/10.1063/PT.3.2979 Arch and scaffold: How Einstein found his field equations] Physics Today November 2015, History of the Development of the Field Equations |

||

*[http://blog.stephenwolfram.com/2016/02/black-hole-tech/ Black Hole Tech?] a computational look at Einstein's Field Equations through programming. |

|||

{{Einstein}} |

{{Einstein}} |

||

Revision as of 15:31, 26 October 2016

| General relativity |

|---|

|

The Einstein field equations (EFE; also known as "Einstein's equations") are the set of 10

Similar to the way that

As well as obeying local energy–momentum conservation, the EFE reduce to

Exact solutions for the EFE can only be found under simplifying assumptions such as

Mathematical form

| Part of a series on |

| Spacetime |

|---|

|

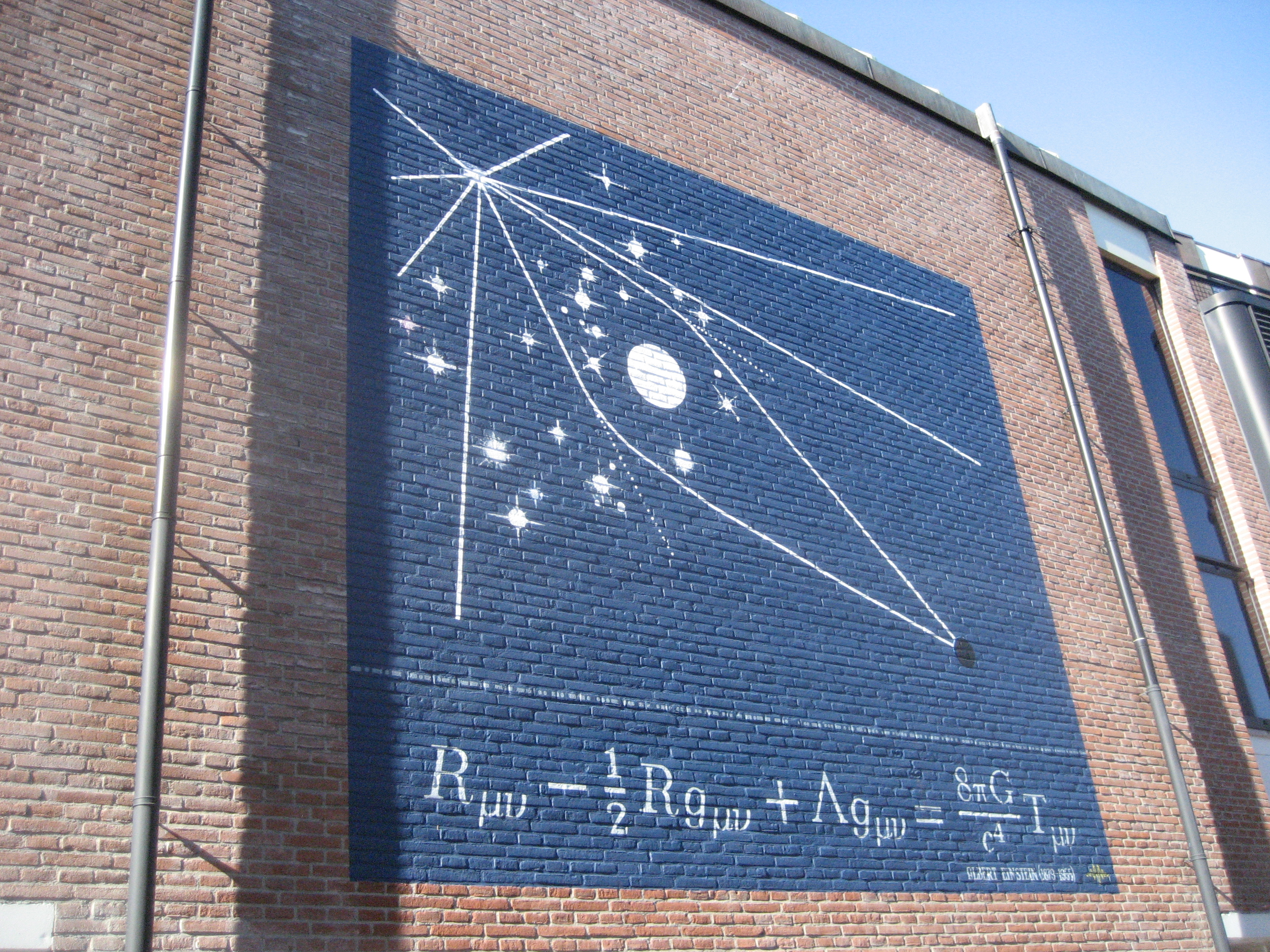

The Einstein field equations (EFE) may be written in the form:[5][1]

The EFE is a

Although the Einstein field equations were initially formulated in the context of a four-dimensional theory, some theorists have explored their consequences in n dimensions. The equations in contexts outside of general relativity are still referred to as the Einstein field equations. The vacuum field equations (obtained when T is identically zero) define Einstein manifolds.

Despite the simple appearance of the equations they are actually quite complicated. Given a specified distribution of matter and energy in the form of a stress–energy tensor, the EFE are understood to be equations for the metric tensor gμν, as both the Ricci tensor and scalar curvature depend on the metric in a complicated nonlinear manner. In fact, when fully written out, the EFE are a system of 10 coupled, nonlinear, hyperbolic-elliptic partial differential equations[citation needed].

One can write the EFE in a more compact form by defining the Einstein tensor

which is a symmetric second-rank tensor that is a function of the metric. The EFE can then be written as

Using

The expression on the left represents the curvature of spacetime as determined by the metric; the expression on the right represents the matter/energy content of spacetime. The EFE can then be interpreted as a set of equations dictating how matter/energy determines the curvature of spacetime.

These equations, together with the

Sign convention

The above form of the EFE is the standard established by Misner, Thorne, and Wheeler.[7] The authors analyzed all conventions that exist and classified according to the following three signs (S1, S2, S3):

The third sign above is related to the choice of convention for the Ricci tensor:

With these definitions Misner, Thorne, and Wheeler classify themselves as (+ + +), whereas Weinberg (1972)[8] is (+ − −), Peebles (1980)[citation needed] and Efstathiou (1990)[citation needed] are (− + +), while Peacock (1994)[citation needed], Rindler (1977)[citation needed], Atwater (1974)[citation needed], Collins Martin & Squires (1989)[citation needed] are (− + −).

Authors including Einstein have used a different sign in their definition for the Ricci tensor which results in the sign of the constant on the right side being negative

The sign of the (very small) cosmological term would change in both these versions, if the (+ − − −) metric sign convention is used rather than the MTW (− + + +) metric sign convention adopted here.

Equivalent formulations

Taking the trace with respect to the metric of both sides of the EFE one gets

where D is the spacetime dimension. This expression can be rewritten as

If one adds −1/2gμν times this to the EFE, one gets the following equivalent "trace-reversed" form

For example, in D = 4 dimensions this reduces to

Reversing the trace again would restore the original EFE. The trace-reversed form may be more convenient in some cases (for example, when one is interested in weak-field limit and can replace gμν in the expression on the right with the

The cosmological constant

Einstein modified his original field equations to include a

Since Λ is constant, the energy conservation law is unaffected.

The cosmological constant term was originally introduced by Einstein to allow for a universe that is not expanding or contracting. This effort was unsuccessful because:

- the universe described by this theory was unstable, and

- observations by expanding.

So, Einstein abandoned Λ, calling it the "biggest blunder [he] ever made".[9]

Despite

Einstein thought of the cosmological constant as an independent parameter, but its term in the field equation can also be moved algebraically to the other side, written as part of the stress–energy tensor:

The resulting vacuum energy is constant and given by

The existence of a cosmological constant is thus equivalent to the existence of a non-zero vacuum energy. Thus, the terms "cosmological constant" and "vacuum energy" are now used interchangeably in general relativity.

Features

Conservation of energy and momentum

General relativity is consistent with the local conservation of energy and momentum expressed as

- .

Derivation of local energy-momentum conservation Contracting the differential Bianchi identity

with gαβ gives, using the fact that the metric tensor is covariantly constant, i.e. gαβ;γ = 0,

The antisymmetry of the Riemann tensor allows the second term in the above expression to be rewritten:

which is equivalent to

using the definition of the

Ricci tensor.Next, contract again with the metric

to get

The definitions of the Ricci curvature tensor and the scalar curvature then show that

which can be rewritten as

A final contraction with gεδ gives

which by the symmetry of the bracketed term and the definition of the Einstein tensor, gives, after relabelling the indices,

Using the EFE, this immediately gives,

which expresses the local conservation of stress–energy. This conservation law is a physical requirement. With his field equations

Nonlinearity

The nonlinearity of the EFE distinguishes general relativity from many other fundamental physical theories. For example,

The correspondence principle

The EFE reduce to

Derivation of Newton's law of gravity Newtonian gravitation can be written as the theory of a scalar field, Φ, which is the gravitational potential in joules per kilogram

where ρ is the mass density. The orbit of a

free-fallingparticle satisfiesIn tensor notation, these become

In general relativity, these equations are replaced by the Einstein field equations in the trace-reversed form

for some constant, K, and the

geodesic equationTo see how the latter reduce to the former, we assume that the test particle's velocity is approximately zero

and thus

and that the metric and its derivatives are approximately static and that the squares of deviations from the

Minkowski metricare negligible. Applying these simplifying assumptions to the spatial components of the geodesic equation giveswhere two factors of dt/dτ have been divided out. This will reduce to its Newtonian counterpart, provided

Our assumptions force α = i and the time (0) derivatives to be zero. So this simplifies to

which is satisfied by letting

Turning to the Einstein equations, we only need the time-time component

the low speed and static field assumptions imply that

So

and thus

From the definition of the Ricci tensor

Our simplifying assumptions make the squares of Γ disappear together with the time derivatives

Combining the above equations together

which reduces to the Newtonian field equation provided

which will occur if

Vacuum field equations

If the energy-momentum tensor Tμν is zero in the region under consideration, then the field equations are also referred to as the vacuum field equations. By setting Tμν = 0 in the trace-reversed field equations, the vacuum equations can be written as

In the case of nonzero cosmological constant, the equations are

The solutions to the vacuum field equations are called

Einstein–Maxwell equations

If the energy-momentum tensor Tμν is that of an

is used, then the Einstein field equations are called the Einstein–Maxwell equations (with cosmological constant Λ, taken to be zero in conventional relativity theory):

Additionally, the covariant Maxwell Equations are also applicable in free space:

where the semicolon represents a

in which the comma denotes a partial derivative. This is often taken as equivalent to the covariant Maxwell equation from which it is derived.[12] However, there are global solutions of the equation which may lack a globally defined potential.[13]

Solutions

The solutions of the Einstein field equations are

The study of exact solutions of Einstein's field equations is one of the activities of cosmology. It leads to the prediction of black holes and to different models of evolution of the universe.

One can also discover new solutions of the Einstein field equations via the method of orthonormal frames as pioneered by Ellis and MacCallum.[15] In this approach, the Einstein field equations are reduced to a set of coupled, nonlinear, ordinary differential equations. As discussed by Hsu and Wainwright,[16] self-similar solutions to the Einstein field equations are fixed points of the resulting dynamical system. New solutions have been discovered using these methods by LeBlanc [17] and Kohli and Haslam.[18]

The linearised EFE

The nonlinearity of the EFE makes finding exact solutions difficult. One way of solving the field equations is to make an approximation, namely, that far from the source(s) of gravitating matter, the

Polynomial form

One might think that EFE are non-polynomial since they contain the inverse of the metric tensor. However, the equations can be arranged so that they contain only the metric tensor and not its inverse. First, the determinant of the metric in 4 dimensions can be written:

using the Levi-Civita symbol; and the inverse of the metric in 4 dimensions can be written as:

Substituting this definition of the inverse of the metric into the equations then multiplying both sides by det(g) until there are none left in the denominator results in polynomial equations in the metric tensor and its first and second derivatives. The action from which the equations are derived can also be written in polynomial form by suitable redefinitions of the fields.[19]

See also

Notes

- ^ ) on 2012-02-06.

- ^ Einstein, Albert (November 25, 1915). "Die Feldgleichungen der Gravitation". Sitzungsberichte der Preussischen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin: 844–847. Retrieved 2006-09-12.

- ) Chapter 34, p. 916.

- ISBN 0-8053-8732-3.

- ISBN 0-09-922391-0.

- ^ Misner, Thorne & Wheeler 1973

- ^ Weinberg 1972

- ISBN 0-670-50376-2. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- ^ Wahl, Nicolle (2005-11-22). "Was Einstein's 'biggest blunder' a stellar success?". Archived from the original on 2007-03-07. Retrieved 2007-03-14.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-19-927583-0.

- ..

- ISBN 0-521-46136-7.

- ^ Ellis, GFR and MacCallum, M, "A class of homogeneous cosmological models", Comm. Math. Phys. Volume 12, Number 2 (1969), 108-141.

- ^ Hsu, L and Wainwright, J, "Self-similar spatially homogeneous cosmologies: orthogonal perfect fluid and vacuum solutions", Class. Quantum Grav. 3 (1986) 1105-1124"

- ^ LeBlanc, V.G, "Asymptotic states of magnetic Bianchi I cosmologies", 1997 Class. Quantum Grav. 14 2281

- ^ Kohli, Ikjyot Singh and Haslam, Michael C, "Dynamical systems approach to a Bianchi type I viscous magnetohydrodynamic model", Phys. Rev. D 88, 063518 (2013)

- ^ Einstein's Field Equations in Polynomial Form

References

See

- ISBN 0-7167-0344-0)

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ISBN 0-471-92567-5

External links

- "Einstein equations", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- Caltech Tutorial on Relativity — A simple introduction to Einstein's Field Equations.

- The Meaning of Einstein's Equation — An explanation of Einstein's field equation, its derivation, and some of its consequences

- Video Lecture on Einstein's Field Equations by MITPhysics Professor Edmund Bertschinger.

- Arch and scaffold: How Einstein found his field equations Physics Today November 2015, History of the Development of the Field Equations

- Black Hole Tech? a computational look at Einstein's Field Equations through programming.

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}g_{\mu \nu }&=[S1]\times \operatorname {diag} (-1,+1,+1,+1)\\[6pt]{R^{\mu }}_{\alpha \beta \gamma }&=[S2]\times (\Gamma _{\alpha \gamma ,\beta }^{\mu }-\Gamma _{\alpha \beta ,\gamma }^{\mu }+\Gamma _{\sigma \beta }^{\mu }\Gamma _{\gamma \alpha }^{\sigma }-\Gamma _{\sigma \gamma }^{\mu }\Gamma _{\beta \alpha }^{\sigma })\\[6pt]G_{\mu \nu }&=[S3]\times {8\pi G \over c^{4}}T_{\mu \nu }\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c42b80cbd0648961fff8774dee776e148caaea74)

![{\displaystyle R_{\mu \nu }=[S2]\times [S3]\times {R^{\alpha }}_{\mu \alpha \nu }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/55a370597ca453317d8e0203c784eac935102a37)

![{\displaystyle R_{\alpha \beta [\gamma \delta ;\varepsilon ]}=\,0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9148435aefd0141d9020d31503eed18bd9adf899)

![{\displaystyle \nabla ^{2}\Phi [{\vec {x}},t]=4\pi G\rho [{\vec {x}},t]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c337a1fef9c665533f8a547cb833d63734d6e814)

![{\displaystyle {\ddot {\vec {x}}}[t]=-\nabla \Phi [{\vec {x}}[t],t]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c12465398ee3dc9fc083606c6f76e2e5813188f9)

![{\displaystyle F_{[\alpha \beta ;\gamma ]}={\frac {1}{3}}\left(F_{\alpha \beta ;\gamma }+F_{\beta \gamma ;\alpha }+F_{\gamma \alpha ;\beta }\right)={\frac {1}{3}}\left(F_{\alpha \beta ,\gamma }+F_{\beta \gamma ,\alpha }+F_{\gamma \alpha ,\beta }\right)=0.\!}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c40aaebcd1caad533ed73ca5664aef7adc10fd9f)