Strandflat

Strandflat (

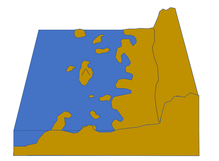

The strandflats are usually bounded on the landward side by a sharp break in slope, leading to mountainous terrain or high plateaux. On the seaward side, strandflats end at submarine slopes.[2][3] The bedrock surface of strandflats is uneven and tilts gently towards the sea.[3]

The concept of a strandflat was introduced in 1894 by Norwegian geologist

Norwegian strandflat

Characteristics

Strandflats are not fully flat and may display some local relief, meaning that it is usually not possible to assign them a precise elevation above sea level.[6] The Norwegian strandflats may go from 70–60 metres (230–200 ft) above sea level to 40–30 metres (131–98 ft) below sea level.[1] The undulations in the strandflat relief may result in an irregular coastline with skerries, small embayments and peninsulas.[2]

The width of the strandflat varies from a few kilometers to 50 km and occasionally reaching up to 80 km in width.[1][6] From land to sea the strandflat can be subdivided into the following zones: the supramarine zone, the skjærgård (skerry archipelago), and the submarine zone. Residual mountains surrounded by the strandflat are called rauks.[7]

On the landward side, the strandflat often terminates abruptly with the beginning of a steep slope that separates it from higher or more uneven terrain.

Overall, strandflats in

Geological origin

Despite being together with fjords the most studied coastal landform in Norway,[10] as of 2013 there is no consensus as to the origin of strandflats.[5] An analysis of the literature shows that during the course of the 20th century, explanations for the strandflat shifted from involving one or two processes to including many more. Thus most modern explanations are of polygenetic type.[11] Grand-scale observations on the distribution of strandflats tend to favour an origin in connection to the Quaternary glaciations, while in-detail studies have led scholars to argue that strandflats have been shaped by chemical weathering during the Mesozoic. According to this second view, the weathered surface would then have been buried in sediments to be freed from this cover during Late Neogene for a final reshaping by erosion.[12] Hans Holtedahl regarded the strandflats as modified paleic surfaces, conjecturing that paleic surfaces dipping gently to the sea would favoured strandflat formation.[8]

In his original description, Reusch regarded the strandflat as originating from

Frost weathering, glaciers and sea ice

The Arctic explorer

In 1929,

Deep weathering and antiquity

Contrary to the glacial and

In 2013, Odleiv and co-workers put forward a mixed origin for the strandflat of Nordland. They argue that this strandflat in northern Norway could represent the remnants of a weathered peneplain of Triassic age[D] that was buried in sediment for long time before made flat again by erosion in Pliocene and Pleistocene times.[5] A 2017 study concerning radiometric dating of illite, a clay formed by weathering, is interpreted to indicate that the strandflat at Bømlo in Western Norway was weathered c. 210 million years ago during Late Triassic times.[12] Haakon Fossen and co-workers disagree with this view citing thermochronology studies to claim that the strandflat in Western Norway was still covered by sedimentary rock in the Triassic and did only got free of its sedimentary cover in the Jurassic. Same authors note that movement of geological faults in the Late Mesozoic imply the strandflats of Western Norway took their final shape after the Late Jurassic or else they would occur at various heights above sea level.[18] A similar opinion is expressed by Hans Holtedahl who wrote that "[t]he strandflat must have formed later the main (Tertiary) uplift of the Scandinavian landmass".[8] To this Holtedahl added that in Trøndelag between Nordland and Western Norway the strandflat could be a surface formed before the Jurassic, then buried in sediments and at some point freed from this cover.[8] In the understanding of Tormod Klemsdal strandflats may be old surfaces shaped by deep weathering that escaped the uplift that affected the Scandinavian Mountains further east.[2]

The strandflat at Bømlo is considered by Ola Fredin and co-workers to be equivalent to the sediment-capped top of

Outside Norway

Strandflats have been identified in high-latitude areas such as the coast of

In

In

Gallery

-

Aerial view of the strandflat at Bømlo.

-

Aerial view of the strandflat at Goddo island near Bømlo.

-

View of the strandflat at Helgeland from the mountain Dønnesfjellet in Dønna. A number of rauks can be seen, from left:Hestmona, Rødøyløva and Lurøyfjellet, all landmarks on the Norwegian Coast.

Explanatory footnotes

- ^ American geographers William Morris Davis and Douglas Wilson Johnson supported the view that marine erosion created the strandflat.[11]

- ^ Later in 2000 Karna Lidmar-Bergström, Cliff Ollier and Jan R. Sulebak did describe the Paleic surface as composed of a sequence of steps but did so only for the upper parts.[15]

- ^ Cirques in the southern half of Norway can be found both near sea level and at 2,000 m.[16]

- ^ Remnants of a peneplain formed in Triassic times do also exist in southwestern Sweden.[17]

Citations

- ^ Store norske leksikon(in Norwegian). Oslo: Kunnskapsforlaget.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4020-3880-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-924590-1.

- ^ ISBN 0-632-05311-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g Olesen, Odleiv; Kierulf, Halfdan Pascal; Brönner, Marco; Dalsegg, Einar; Fredin, Ola; Solbakk, Terje (2013). "Deep weathering, neotectonics and strandflat formation in Nordland, northern Norway". Norwegian Journal of Geology. 93: 189–213.

- ^ a b c d Dawson, Alasdair D. (2004). "Strandflat". In Goudie, A.S. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Geomorphology. Routledge. pp. 345–347.

- ^ ISBN 82-7671-104-9. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Holtedahl, Hans (1998). "The Norwegian strandflat puzzle" (PDF). Norsk Geologisk Tidsskrift. 78: 47–66.

- ^ Setså, Ronny (2018). "Mange jordskjelv på strandflaten". geoforskning.no (in Norwegian). Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-4020-8638-0.

- ^ .

- ^ PMID 28452366.

- ^ Norwegian Geological Survey. October 25, 2011. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- .

- .

- doi:10.1130/g34806.1.

- .

- ^ PMID 29138403.

- .

- ^ Chalmers, M.; Clapperton, M.A. (1970). Geomorhpology of the Strombness Bay — Cumberland Bay area, South Georgia (PDF) (Report). British Antarctic Survey Scientific Reports. Vol. 70. pp. 1–25. Retrieved January 29, 2018.

- ^ Serrano, Enrique; López-Martínez, Jerónimo (1997). "Geomorfología de la península Coppermine, isla Robert, islas Shetland del Sur, Antártica" (PDF). Serie Científica (in Spanish). 47: 19–29.

- S2CID 130965005.

General literature

- Holtedahl, Hans (1959). "Den norske strandflate. Med særlig henblikk på dens utvikling i kystområdene på Møre". Norwegian Journal of Geography. 16: 285–385.

- Nansen, Fridtjof (1904). "The Bathymetrical Features of the North Polar Seas". In Nansen F. (ed.): The Norwegian North Polar Expedition 1893–1896. Scientific results, Vol IV. J. Dybwad, Christiania, 1–232.

- Reusch, Hans(1894). Strandflaten, et nyt træk i Norges geografi. Norges geologiske undersokelse, 14, 1–14.