Typhoon Tip

| IBTrACS | |

Part of the 1979 Pacific typhoon season |

Typhoon Tip, known in the Philippines as Super Typhoon Warling, was the largest and most intense

U.S. Air Force aircraft flew 60 weather reconnaissance missions into the typhoon, making Tip one of the most closely observed tropical cyclones.[1] Rainfall from Tip indirectly led to a fire that killed 13 Marines and injured 68 at Combined Arms Training Center, Camp Fuji in the Shizuoka Prefecture of Japan.[2] Elsewhere in the country, the typhoon caused widespread flooding and 42 deaths; offshore shipwrecks left 44 people killed or missing.

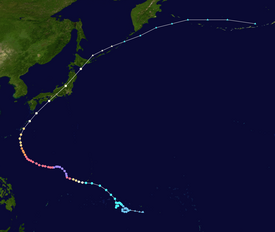

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

At the end of September 1979, three circulations developed within the

While executing another loop near Chuuk, the tropical depression intensified into Tropical Storm Tip, though the storm failed to organize significantly due to the influence of Tropical Storm Roger. Reconnaissance aircraft provided the track of the surface circulation, since satellite imagery estimated the center was about 60 km (37 mi) from its true position. After drifting erratically for several days, Tip began a steady northwest motion on October 8. By that time, Tropical Storm Roger had become an

Owing to very favorable conditions for development, Typhoon Tip

After peaking in intensity, Tip weakened to 230 km/h (145 mph) and remained at that intensity for several days, as it continued west-northwestward. For five days after its peak strength, the average radius of winds stronger than 55 km/h (35 mph) extended over 1,100 km (684 mi). On October 17, Tip began to weaken steadily and decrease in size, recurving northeastward under the influence of a mid-level

Impact

| Typhoon | Season | Pressure | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hPa | inHg | |||

| 1 | Tip | 1979 | 870 | 25.7 |

| 2 | June

|

1975 | 875 | 25.8 |

| Nora | 1973 | |||

| 4 | Forrest | 1983 | 876[6] | 25.9 |

| 5 | Ida | 1958 | 877 | 25.9 |

| 6 | Rita | 1978 | 878 | 26.0 |

| 7 | Kit | 1966 | 880 | 26.0 |

| Vanessa | 1984 | |||

| 9 | Nancy | 1961 | 882 | 26.4 |

| 10 | Irma

|

1971 | 884 | 26.1 |

| 11 | Nina

|

1953 | 885 | 26.1 |

| Joan | 1959 | |||

| Megi | 2010 | |||

| Source: JMA Typhoon Best Track Analysis Information for the North Western Pacific Ocean.[7] | ||||

The typhoon produced heavy rainfall early in its lifetime while passing near Guam, including a total of 23.1 cm (9.1 in) at

Heavy rainfall from the typhoon breached a flood-retaining wall at

During recurvature, Typhoon Tip passed about 65 km (40 mi) east of

Records and meteorological statistics

Typhoon Tip was the largest tropical cyclone on record, with a diameter of 1,380 mi (2,220 km)—almost double the previous record of 700 mi (1,130 km) in diameter set by Typhoon Marge in August 1951.[20][21][22] At its largest, Tip was nearly half the size of the contiguous United States.[23] The temperature inside the eye of Typhoon Tip at peak intensity was 30 °C (86 °F) and described as exceptionally high.[1] With 10-minute sustained winds of 160 mph (260 km/h), Typhoon Tip is the strongest cyclone in the complete tropical cyclone listing by the Japan Meteorological Agency.[4]

The typhoon was also the most intense tropical cyclone on record, with a pressure of 870 mbar (25.69 inHg), 5 mbar (0.15 inHg) lower than the previous record set by

Despite the typhoon's intensity and damage, the name Tip was not retired and was reused in 1983, 1986, and 1989.[4] The name was discontinued from further use in 1989, when the JTWC changed their naming list.[29]

See also

- List of tropical cyclone records

- Other notable tropical cyclones that broke records:

- )

- Typhoon Nancy (1961) - An extremely powerful typhoon that unofficially had the strongest winds ever recorded in a typhoon, with maximum 1-minute sustained winds at 215 mph (346 km/h), tying Hurricane Patricia

- Tropical Storm Marco (2008) – The smallest tropical cyclone on record

- Hurricane Patricia (2015)– Second-most intense tropical cyclone, most intense ever recorded in the Western Hemisphere, with the highest maximum 1-minute sustained winds recorded in a tropical cyclone, at 215 mph (346 km/h)

- ). Also became the most intense landfalling tropical cyclone on record, impacting with same pressure

- Typhoon Goni (2020)– A Category 5-equivalent super typhoon that became the strongest landfalling storm on record, with 1-minute sustained winds of 195 mph (314 km/h)

- Typhoon Haiyan (2013) - The deadliest Philippine typhoon in modern history

- Cyclone Freddy (2023)- The longest lasting tropical cyclone ever recorded.

- Other notable tropical cyclones that impacted Japan:

- Typhoon Vera (1959)- The strongest storm to ever impact Japan, with maximum sustained wind speeds of 160 mph (260 km/h) upon landfall - Comparable to a Category 5-equivalent super typhoon

- Typhoon Wipha (2013) - Similar impacts and dissipation

- Typhoon Lan (2017) – Another very large and powerful typhoon

- Typhoon Jebi (2018) – A typhoon that took a slightly similar track path and struck Japan as a Category 2-equivalent typhoon; caused substantial damage, primarily in the Kansai region

- Typhoon Trami (2018)– A Category 5-equivalent super typhoon that affected the same general area

- Typhoon Hagibis (2019)– A typhoon that took almost similar track path, similar size, similar landfall date and struck Japan as a Category 2-equivalent typhoon; caused tremendous damage and marked the 40th anniversary of Tip

- Hypercane

Notes

- ^ All wind speeds in the article are maximum sustained winds sustained for one minute, unless otherwise noted.

References

- ^ ISSN 1520-0493.

- ^ Little, Vince (2007-10-19). "Marines recall 1979 fire at Camp Fuji that claimed 13 lives". Stars and Stripes. Archived from the original on 2018-10-17. Retrieved 2016-07-25.

- ^ "1979 ATCR TABLE OF CONTENTS". Pearl Harbor, Hawaii: Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 1978. Archived from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2021-05-12.

- ^ a b c d Japan Meteorological Agency (2010-01-12). "Best Track for Western North Pacific Tropical Cyclones". Archived from the original (TXT) on 2013-06-25. Retrieved 2010-01-12.

- ^ "The speediest and deadliest cyclones in the world". Financial Express. 14 June 2020. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

- ^ "World Tropical Cyclone Records". World Meteorological Organization. Arizona State University. Retrieved December 12, 2013.

- ^ Japan Meteorological Agency. "RSMC Best Track Data (Text)" (TXT).

- ^ Tropical Cyclones Affecting Guam (1671-1990) (PDF) (Report). Joint Typhoon Warning Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 2013-11-24. Retrieved 2007-01-25.

- ^ a b c "History of the U.S. Naval Mobile Construction Battalion FOUR". U.S. Naval Construction Force. 2004. Archived from the original on 2007-02-05. Retrieved 2007-01-25.

- ^ a b c "Camp Fuji Fire Memorial". United States Marine Corps. 2006-08-03. Archived from the original on February 25, 2008. Retrieved 2007-01-25.

- ^ "Second U.S. Marine Dies In Typhoon-Caused Fire". The Washington Post. 1979-10-20.

- ^ "Marine Killed in Japanese Typhooe [sic]". The Washington Post. 1979-10-20.

- Palm Beach Post. 1979-10-20.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "25 are killed as Typhoon Tip crosses Japan". The Globe and Mail. Reuters. 1979-10-20.

- ^ "International News". Associated Press. 1979-10-19.

- ^ "International News". Associated Press. 1979-10-18.

- ^ "Digital Typhoon: Typhoon 197920 (TIP) - Disaster Information". Digital Typhoon Disaster Database. National Institute of Informatics. Retrieved April 30, 2023.

- ^ "International News". Associated Press. 1979-10-22.

- ^ National Weather Service Southern Region Headquarters (2010-01-05). "Tropical Cyclone Structure". JetStream - Online School for Weather: Tropical Weather. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 2013-12-07. Retrieved 2008-12-28.

- ISBN 978-0-312-37152-4. Archivedfrom the original on 2015-03-22. Retrieved 2016-07-15.

- ^ Steve Stone (2005-09-22). "Rare Category 5 hurricane is history in the making". The Virginia Pilot. Archived from the original on 2012-01-20. Retrieved 2011-12-31.

- ^ M. Ragheb (2011-09-25). "Natural Disasters and Man made Accidents" (PDF). University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-26. Retrieved 2011-12-31.

- ISBN 978-0-8078-3068-0.

- ^ National Weather Service (2005). "Super Typhoon Tip". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved 2014-06-23.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b Karl Hoarau; Gary Padgett; Jean-Paul Hoarau (2004). Have there been any typhoons stronger than Super Typhoon Tip? (PDF). 26th Conference on Hurricanes and Tropical Meteorology. Miami, Florida: American Meteorological Society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-11-09. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- ^ Satellite Services Division (2013). "Typhoon 31W". National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service. Archived from the original on November 11, 2013. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

- ^ Todd B. Kimberlain; Eric S. Blake; John P. Cangialosi (February 1, 2016). Hurricane Patricia (PDF) (Report). Tropical Cyclone Report. Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ Robert J. Plante; Charles P. Guard (6 July 1990). 1989 Annual Tropical Cyclone Report (PDF). Joint Typhoon Warning Center (Report). Pearl Harbor, Hawaii. Retrieved 2 May 2021.

External links

Media related to Typhoon Tip at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Typhoon Tip at Wikimedia Commons