Wallace Stegner

Wallace Stegner | |

|---|---|

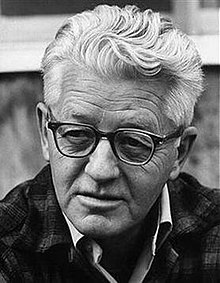

Stegner c. 1969 | |

| Born | Wallace Earle Stegner February 18, 1909 Lake Mills, Iowa, U.S. |

| Died | April 13, 1993 (aged 84) Santa Fe, New Mexico, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Education | |

| Spouse | Mary Stuart Page (1934–1993) |

| Children | Page Stegner |

Wallace Earle Stegner (February 18, 1909 – April 13, 1993) was an American novelist, writer, environmentalist, and historian. He was often called "The Dean of Western Writers".[1] He won the Pulitzer Prize in 1972[2] and the U.S. National Book Award in 1977.[3]

Personal life

Stegner was born in

In 1934, Stegner married Mary Stuart Page. For 59 years they shared a "personal literary partnership of singular facility," in the words of

Stegner's son, Page Stegner, was a novelist, essayist, nature writer and professor emeritus at University of California, Santa Cruz. Page was married to Lynn Stegner, a novelist.[10][11] Page co-authored American Places and edited the 2008 Collected Letters of Wallace Stegner.[12] He was Thomas Heggen's cousin.[13][14]

Activism

In the 1940s, Stegner was a leading member of the Peninsula Housing Association, a group of locals in Palo Alto aiming to build a large co-operative housing complex for Stanford University faculty and staff on a 260-acre ranch the group had purchased near campus.[15] Private lenders and the Federal Housing Authority would not provide financing to the group because three of the families were African-American. Rather than be a party to housing discrimination by proceeding without these families, the group abandoned the project and eventually sold the land.

Career

Stegner taught at the

Stegner's novel Angle of Repose (first published by Doubleday in early 1971) won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1972.[2] It was based on the letters of Mary Hallock Foote (first published in 1972 by Huntington Library Press as the memoir A Victorian Gentlewoman in the Far West). Stegner explained his use of unpublished archival letters briefly at the beginning of Angle of Repose but his use of uncredited passages taken directly from Foote's letters caused a continuing controversy.[17][18]

In 1977 Stegner won the National Book Award for The Spectator Bird.[3] In 1992, he refused a National Medal from the National Endowment for the Arts because he believed the NEA had become too politicized. Stegner's semi-autobiographical novel Crossing to Safety (1987) gained broad literary acclaim and commercial popularity.

Stegner's non-fiction works include Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West (1954), a biography of John Wesley Powell, the first white man to explore the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon. Powell later served as a government scientist and was an advocate of water conservation in the American West. Stegner wrote the foreword to and edited This Is Dinosaur, with photographs by Philip Hyde. The Sierra Club book was used in the campaign to prevent dams in Dinosaur National Monument and helped launch the modern environmental movement. A substantial number of Stegner's works are set in and around Greensboro, Vermont, where he lived part-time. Some of his character representations (particularly in Second Growth) were sufficiently unflattering that residents took offense, and he did not visit Greensboro for several years after its publication.[19]

Legacy

On the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Stegner's birth, Timothy Egan reflected in The New York Times on the writer's legacy, including his perhaps troubled relationship with the newspaper itself. Over 100 readers including Jane Smiley offered comments on the subject.[20]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

In recognition of Stegner's legacy at the University of Utah, The Wallace Stegner Prize in Environmental or American Western History was established in 2010 and is administered by the University of Utah Press. This book publication prize is awarded to the best monograph the Press receives on the topic of American western or environmental history within a predetermined time period.[21]

The

In 2005, the Los Altos History Museum mounted an exhibition entitled "Wallace Stegner: Throwing a Long Shadow" providing a retrospective of the author's life and works.

In May 2011, the San Francisco Chronicle reported that Stegner's Los Altos Hills home, which was sold in 2005, was scheduled to be demolished by the current owners. Lynn Stegner said the family attempted to sell the home to Stanford University in an attempt to preserve it, but the university said the home would be sold at market value, customary for real estate donated to Stanford. Wallace Stegner's wife, Mary, said that Wallace would disapprove of the fuss surrounding the issue.[23] Wallace initially opposed the creation of a hiking path near his home but Mary Stegner confided that her husband later came to enjoy walking on it, and the path was eventually named for him posthumously, in 2008.[24]

In August 2016 a public charter school called the Wallace Stegner Academy opened in Salt Lake City, Utah.[25] The school was named after Wallace Stegner because the founders valued people like Stegner who are devoted to academics and pursue the advancement of knowledge and art throughout their entire lives.

The Wallace Earle Stegner papers (Ms0676), 1935–2004, can be found at the University of Utah Marriott Library Special Collections Manuscripts Division. With 29 boxes and 139 linear feet, the collections contains personal and professional correspondence, journals, manuscript drafts for work both published and unpublished, research material, memorabilia, scrapbooks, books containing letters of condolence compiled by Mary Stegner, and Wallace's personal typewriter.[26]

The Wallace Stegner Research Collection: 1942–1996, Collection 2443, can be found at the Montana State University Archives and Special Collections in Bozeman, Montana. This collection of published materials and correspondence by and about Stegner was compiled by Nancy Colberg, a librarian and the author of Wallace Stegner: A Descriptive Bibliography and former owner of Willow Creek Books in Denver, Colorado.[27][28] The materials were sold to the Archives in 2001. The collection contains Stegner articles and short stories from newspapers and periodicals, published interviews and articles about Stegner and his work, and personal and professional correspondence.[28] A smaller collection of materials relating to Stegner gathered by Thomas H. Watkins was later added to Collection 2443. The collection is divided into four series with a total of 7 boxes or 3.2 linear feet.[28]

Bibliography

- Novels

- Remembering Laughter (1937)

- The Potter's House (1938)

- On a Darkling Plain (1940)

- Fire and Ice (1941)

- The Big Rock Candy Mountain (1943), semi-autobiographical

- Second Growth (1947)

- The Preacher and the Slave (1950), reissued as Joe Hill: A Biographical Novel

- A Shooting Star (1961)

- All the Little Live Things (1967)

- Joe Hill: A Biographical Novel (1969)

- Angle of Repose (1971), winner of the Pulitzer Prize[2]

- The Spectator Bird (1976), winner of the National Book Award[3]

- Recapitulation (1979)

- Crossing to Safety (1987)

- Collections

- The Women on the Wall (1950)

- The City of the Living: And Other Stories (1957)

- Writer's Art: A Collection of Short Stories (1972)

- One Way to Spell Man: Essays with a Western Bias (1982)

- The American West as Living Space (1987)[29]

- Collected Stories of Wallace Stegner (1990)

- Late Harvest: Rural American Writing (1996), with Bobbie Ann Mason

- Chapbooks

- Genesis: A Story from Wolf Willow (1994)

- Nonfiction

- Clarence Edward Dutton: An Appraisal (1936)

- Mormon Country (1942, American Folkways series)

- One Nation (1945), with the editors of Look magazine

- Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and the Second Opening of the West (1954)

- Wolf Willow: A History, a Story, and a Memory of the Last Plains Frontier (1962), autobiography

- Wilderness Letter (1960) [Note 1]

- The Gathering of Zion: The Story of the Mormon Trail (1964)

- Teaching the Short Story (1966)

- The Sound of Mountain Water (1969)

- Discovery! The Search for Arabian Oil (1971)

- The Uneasy Chair: A Biography of Bernard DeVoto (1974)

- Writer in America (1982)

- Conversations with Wallace Stegner on Western History and Literature (1983)

- This Is Dinosaur: Echo Park Country and its Magic Rivers (1985)

- American Places (1985)

- On the Teaching of Creative Writing (1988)

- Where the Bluebird Sings to the Lemonade Springs: Living and Writing in the West (1992), autobiographical

- Short Stories

- "Bugle Song" (1938)

- "Chip Off the Old Block" (1942)

- "Hostage" (1943)

Awards

- 1937 Little Brown Prize for Remembering Laughter

- 1945 Houghton-Mifflin Life-in-America Award and the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for One Nation[31]

- 1950–1951 Rockefeller fellowship to teach writers in the Far East[31]

- 1953 Wenner-Gren Foundation grant[31]

- 1956 Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences fellowship[31]

- 1967 Commonwealth Club Gold Medal for All the Little Live Things

- 1972 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for Angle of Repose[2]

- 1976 Commonwealth Club Gold Medal for The Spectator Bird

- 1977 National Book Award for Fiction for The Spectator Bird[3]

- 1980 Los Angeles Times Kirsch awardfor lifetime achievement

- 1990 P.E.N. Center USA West award for his body of work

- 1991 California Arts Council award for his body of work

- 1991 Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement[32]

- 1992 National Endowment for the Arts (refused)[clarification needed]

Plus: Three

The Encyclopedia of World Biography reports that the Little Brown prize was for "$2500, which at that time was a fortune. The book became a literary and financial success and helped gain Stegner [the] position ... at Harvard."[31]

References

- Notes

- Timeline of environmental events and the full text of the letter at The Wilderness Society Web site. Retrieved 2-24-09.

- Citations

- ^ Evelyn Boswell (October 5, 2006). "New Stegner professor to hit the ground running". Montana State University News Service. Archived from the original on August 20, 2007. Retrieved September 9, 2007.

- ^ a b c d "Fiction" Archived January 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Past winners & finalists by category. The Pulitzer Prizes. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "National Book Awards – 1977" Archived April 6, 2019, at the Wayback Machine. National Book Foundation. Retrieved 2012-03-29.

(With essay by Harold Augenbraum from the Awards 60-year anniversary blog.) - ^ Stegner, Wallace (1992). Where the Bluebird Sings to the Lemonade Springs. Random House., back cover.

- ^ Wilson, John (May 18, 2008). "That Stegner Fellow". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 4, 2018. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ "Wallace Stegner". Wilderness.net. Archived from the original on March 6, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ "Wallace Stegner Biography". eNotes. Archived from the original on May 12, 2010. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ William H. Honan (April 15, 1993). "Wallace Stegner Is Dead at 84; Pulitzer Prize-Winning Author". New York Times. Archivedfrom the original on June 4, 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ Wallace Stegner Biography Archived October 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. by James R. Hepworth The Quiet Revolutionary. Retrieved 2-24-09.

- ^ "Lynn Stegner Interview: Wallace Stegner Documentary" Archived February 25, 2009, at the Wayback Machine John Howe, interviewer; KUED-TV, n.d. Retrieved 2-19-09

- ^ Biography: Lynn Stegner Archived June 27, 2009, at the Wayback Machine University of Nebraska Press. Retrieved 2-19-09.

- ^ "The power of his pen - The Selected Letters of Wallace Stegner" Archived July 10, 2012, at archive.today Review by Susan Salter Reynolds, LA Times, November 18, 2007. Retrieved 3-12-09.

- ISBN 978-0-253-01281-4.

- ISBN 978-0-520-25957-7.

- ISBN 9781631494536.

- ^ "Committee for Green Foothills". Archived from the original on July 7, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ Mary Ellen Williams Walsh, 'Angle of Repose and the Writings of Mary Hallock Foote: A Source Study,' in Critical Essays on Wallace Stegner, edited by Anthony Arthur, G. K. Hall & Co., 1982, pp. 184-209.

- ^ "A Classic, or A Fraud? Plagiarism allegations aimed at Stegner's Angle of Repose won't be put to rest" Archived September 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine by Philip L. Fradkin, Los Angeles Times, February 3, 2008, sec. M, p. 8. Link upgraded 2-19-09.

- ^ Joseph Gresser, "Wallace Stegner’s birthday celebrated with a hike and some talk Archived September 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, The Chronicle (Barton, Vermont), September 20, 2009.

- ^ Egan, Timothy (February 18, 2009). "Stegner's Complaint". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- ^ "Stegner Prize". University of Utah Press. Archived from the original on April 25, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ Stegner House Web site. Archived August 25, 2005, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2-24-09.

- ^ Whiting, Sam (May 14, 2011). "Wallace Stegner's studio destined for demolition". San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on May 16, 2011. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- ^ L. A. Chung (May 15, 2011). "Writer Wallace Stegner's Home Appears Headed for Demolition". Los Altos Patch. Archived from the original on August 29, 2011. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ "Wallace Stegner | Home". wsacharter.org. Archived from the original on March 11, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- ^ "Wallace Earle Stegner papers, 1935-2004". Special Collections Manuscripts Division, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah. Archived from the original on February 4, 2016. Retrieved February 3, 2016. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- ^ "Wallace Stegner: A Descriptive Bibliography by Nancy Colberg: Fine Hardcover (1990) Signed by Author(s) | The Book Lair, ABAA". www.abebooks.com. Archived from the original on January 15, 2023. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Collection 2443 - Wallace Stegner Research Collection, 1942-1996 - MSU Library | Montana State University". www.lib.montana.edu. Archived from the original on March 10, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- ISBN 0-472-06375-8

- ^ stegner100.com Archived April 3, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Stegner Centennial Utah Web site. Retrieved 2-24-09.

- ^ Thomson Gale. 2004. Retrieved 2-24-09.

- American Academy of Achievement. Archivedfrom the original on June 8, 2020. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

Further reading

- Arthur, Anthony, ed (1982). Critical Essays on Wallace Stegner. G. K. Hall & Co.

- Benson, Jackson J. (1984). Wallace Stegner: His Life and Work.

- Fradkin, Philip L. (2007). "Wallace Stegner's Formative Years in Saskatchewan and Montana" in Montana: The Magazine of Western History Archived October 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Winter 2007, Vol. 57, No. 4, pp. 3–19.

- Fradkin, Philip L. (2008). Wallace Stegner and the American West.

- Gessner, David (2015). All the Wild That Remains: Edward Abbey, Wallace Stegner, and the American West. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 978-0-393-08999-8.

- Hepworth, James R. (1998). Stealing Glances: Three Interviews with Wallace Stegner Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ASIN: B0014JC0I6.

- Steensma, Robert C. (2007). "A Residual Frontier Town: Wallace Stegner's Salt Lake City" in Montana: The Magazine of Western History Archived October 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Winter 2007, Vol. 57, No. 4, pp. 20–23)

- Steensma, Robert C. (2007). Wallace Stegner's Salt Lake City, Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, ISBN 978-0-87480-898-8.

- Stegner, Page, ed (2008). The Selected Letters of Wallace Stegner Shoemaker & Hoard, ISBN 978-1-58243-446-9.

- Stegner, Wallace (1983). Conversations with Wallace Stegner on Western History and Literature. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

- Topping, Gary (2003). Utah Historians and the Reconstruction of Western History Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, ISBN 0-8061-3561-1.

- Willrich, Patricia Rowe (1991). "A Perspective on Wallace Stegner" (1991) in Virginia Quarterly Review Archived December 28, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Spring 1991, pp. 240–59.

External links

- James R. Hepworth (Summer 1990). "Wallace Stegner, The Art of Fiction No. 118". The Paris Review. Summer 1990 (115).

- The Wallace Stegner Environmental Center website

- Books by Wallace Stegner: An Annotated Bibliography

- Website for PBS Wallace Stegner documentary

- Web site for Wallace Stegner at Marriott Library, University of Utah

- Wallace Stegner Bio from San Francisco Public Library

- Wallace Stegner Bio on Answers.com

- Profile of Stegner marriage, on Beyond the Margins

- Committee for Green Foothills

- Wallace Earle Stegner papers finding aid, 1935-2004

- Wallace Earle Stegner photograph collection finding aid, Early 1900s-1980s

- Wallace Stegner photo collection

- "Wallace Stegner". JSTOR.

- Western American Literature Journal: Wallace Stegner

- Collection 2443: Wallace Stegner Research Collection, 1942-1996. Collections includes correspondence, published materials, newspaper clippings, and more. Held at Montana State University's Archives and Special Collections.