William S. Hamilton

William S. Hamilton | |

|---|---|

| |

| Representative to the Legislative Assembly of the Wisconsin Territory from Iowa County | |

| In office December 5, 1842 – December 4, 1843 Serving with Robert M. Long and Moses Meeker | |

| Preceded by | Thomas Jenkins, David Newland, Ephraim F. Ogden, and Daniel M. Parkison |

| Succeeded by | George Messersmith, Robert M. Long, and Moses Meeker |

| Member of the Illinois House of Representatives from the Sangamon County district | |

| In office November 15, 1824 – December 4, 1826 | |

| Preceded by | Stephen Stillman |

| Succeeded by | Elijah Iles |

| Personal details | |

| Born | William Stephen Hamilton August 4, 1797 Albany, New York, U.S. |

| Died | October 9, 1850 (aged 53) Sacramento, California, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Cholera |

| Resting place | Sacramento City Cemetery, Sacramento, California |

| Parents |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Illinois Militia |

| Years of service | 1827, 1832 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Commands | Galena Mounted Volunteers, various U.S. aligned indigenous bands |

| Battles/wars | Winnebago War, Black Hawk War |

William Stephen Hamilton (August 4, 1797 – October 9, 1850), a son of

Early life

William Stephen Hamilton

William was a month shy of his seventh birthday in 1804 when his father was killed in a duel with Vice President

Career

Political and militia service

Hamilton first held elected office in 1824 as a member of the

In late 1827, Hamilton served during the

During the April–August 1832

In June, Hamilton's return to Fort Hamilton with a large group of militia-aligned Native Americans coincided with the arrival of one of the survivors of the June 14 Spafford Farm massacre. The survivor, Francis Spencer, arrived at the fort around the same time as Hamilton did - accompanied by U.S. aligned Menominee.[12][13] Afraid that the fort, like his party at the farm, had also been attacked, Spencer retreated back into the woods. He avoided the fort for between six and nine days, when hunger finally drove him into the open and he realized his mistake.[12][14] On June 16, about an hour after the fight at Horseshoe Bend, Hamilton arrived on the battlefield with U.S. aligned Menominee, Sioux and Ho-Chunk warriors.[15] According to Dodge, the warriors were given some of the scalps his men had taken, with which they were "delighted".[15] Dodge also reported that the allied warriors then proceeded onto the battlefield and mutilated the corpses of the fallen Kickapoo.[15]

Wisconsin Territory politics

Hamilton (a

Mining career

When Hamilton moved from Illinois to Wisconsin in the late 1820s he established a

His mother visited Hamilton at Hamilton's Diggings during the winter of 1837–38.[20] During the same period, Hamilton briefly owned the Mineral Point Miners' Free Press; he sold it to a group from Galena and the paper became known as the Galena Democrat.[21]

When gold was discovered in California, in 1848, gold fever spread into the Midwest lead-mining region. Hamilton set out for California, arriving in 1849, with high hopes, and new equipment. His life in the west would prove to be a disappointment and he later regretted moving there. Hamilton told a friend in California that he would "rather have been hung in the 'Lead Mines' than to have lived in this miserable hole (California)."[8]

Personal life; illness and death

Hamilton never married and presented a rough, garish appearance.[20]

Hamilton had been in California about one year when he died from what he called "mountain fever",[8] most likely cholera during an 1850 epidemic. Before his death Hamilton fell ill for two weeks. He suffered multiple symptoms, including dysentery, and, according to his doctor, died from "malarial fever resulting in spinal exhaustion terminating in paralysis superinduced by great bodily and mental strain."[8]

William S. Hamilton died in Sacramento, California, on October 9, 1850, at age 53.[5] He was interred in the Sacramento Historic City Cemetery.[22] The section of the cemetery where he is buried was named Hamilton Square in his honor.[23]

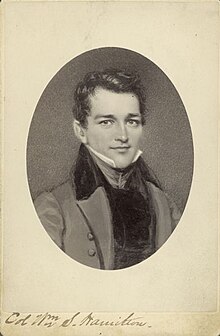

Misidentified Portrait

A portrait of William S. Hamilton is commonly misidentified in books, publications, and on the internet as that of his older brother Philip Hamilton who was killed in a duel in 1801. More recent research by A.K. Fielding author of Rough Diamond: The Life of William Stephen Hamilton [24] published 2021 by Indiana University Press, cites the Wisconsin Historical Society has in their collection a letter dated 1880 from Philip Hamilton II identifying the image as a photo of a miniature portrait of his older brother William. Another source identifying the image as William was published in 1903 titled The Black Hawk War by Frank E. Stevens. Further support of the portrait's misidentification can be found in a closer study of the clothing of the man in the portrait who is dressed in a style more indicative of the 1820s which would more align with William's age than Philip's. A.K. Fielding states in her book[24] "Further research with the help of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation revealed that the clothing worn by the young man in the photograph indeed reflected nineteenth-century fashion." William's nephew Allan McLane Hamilton published the portrait mistakenly identified as Philip Hamilton in his 1910 book about his grandfather and has been the only citation in its widespread use and misidentification.

Images

-

Hamilton Square, Sacramento City Cemetery (plaque)

-

Hamilton Square, Sacramento City Cemetery

-

Hamilton's grave monument

-

Hamilton's grave monument (closeup). The image is of his father.

References

- aide de camp to Illinois Governor Edward Coles, Hamilton's name was recorded as "William Schuyler Hamilton". This was incorrect. See Reed, The Bench and Bar of Wisconsin.

- ISBN 978-1-59420-009-0., chapter "Too near the sun"

- ^ a b c d e f Reed, Parker McCobb. The Bench and Bar of Wisconsin, (Google Books), Reed: 1882, pp. 427–28. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ISBN 0442261136), p. 188. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ a b Lusk, David W. Politics and Politicians: A Succinct History of the Politics of Illinois From 1856–1884, (Google Books), H. W. Rokker: 1884, pp. 455–56. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- Smith, William Rudolph. The History of Wisconsin: In Three Parts, Historical, Documentary, and Descriptive, (Google Books), B. Brown: 1854, pp. 339–42. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- Ford, Thomas. A History of Illinois, from Its Commencement as a State in 1818 to 1847, (Google Books), Ivison & Phinney: 1854, pp. 58–59. Retrieved September 26, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f Gara, Larry. ed. "William S. Hamilton on the Wisconsin Frontier: A Document," (PDF[permanent dead link]), Wisconsin Magazine of History, Vol. 41, No. 1, Autumn, 1957, pp. 25–28. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ Putnam, James William (1918). The Illinois and Michigan Canal: A Study In Economic History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 15. Retrieved December 18, 2013.

- ^ "Muster Role of Captain William Hamilton's Company, via Old Lead Regional Historical Society, transcribed by Jim Hanson and Marjorie Smith from muster rolls in Record Group 94 at the National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D. C. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ Smith, The History of Wisconsin: In Three Parts, Historical, Documentary, and Descriptive, p. 263.

- ^ a b ; Reprinted as: Wakefield's History of the Black Hawk War, Original Publication: Jacksonville, Ill.: Calvin Goudy, 1834. Reprint Publication: Chicago: The Caxton Club, 1908, Chapter 4, Section 70. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ a b Butterfield, Consul Willshire. History of Lafayette County, Wisconsin, (Google Books), Western Historical Co.: 1881, p. 476. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ISBN 0805077588).

- ^ a b c "June 16: Henry Dodge Describes The Battle of the Pecatonica Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine," Historic Diaries: The Black Hawk War, Wisconsin State Historical Society. Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ Schafer, Joseph, ed. The Rump Council Separate No. 211 from the Proceedings of the Society for 1920. Madison: The State Historical Society of Wisconsin [1920?]; pp. 151-152 and passim

- ^ Wisconsin, State Historical Society of (1921). Proceedings of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin. Madison: The Society. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ ISBN 0803282931). Retrieved September 25, 2007.

- ^ Trask, Black Hawk: The Battle for the Heart of America, p. 62.

- ^ ISBN 0803297939), p. 6. Retrieved September 26, 2007.

- Thwaites, Reuben Gold and Bradley, Isaac Samuel. Annotated Catalogue of Newspaper Files in the Library of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin, (Google Books), Democratic Printing Co.: 1898, p. 164. Retrieved September 26, 2007.

- ^ Self Guided Tour (PDF). Historic City Cemetery, Inc. January 2006. Retrieved January 29, 2011.

- ^ Old City Cemetery Committee, Inc.. "Hamilton Square Perennials", Sacramento, 2005. Retrieved on 2010-09-29.

- ^ a b Fielding, A.K. (June 8, 2021). Rough Diamond: The Life of Colonel William Stephen Hamilton, Alexander Hamilton's Forgotten Son. Indiana University Press. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-0-253-05397-8. OCLC 1193557853.