Alwalkeria

| Alwalkeria | |

|---|---|

| |

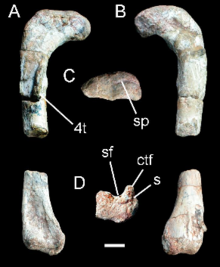

| Holotype saurischian femur in multiple views[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Genus: | †Alwalkeria Chatterjee & Creisler, 1994 |

| Species: | †A. maleriensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Alwalkeria maleriensis (Chatterjee, 1987)

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Alwalkeria (/ˌælwɔːˈkɪəriə/; "for Alick Walker") is a genus partly based on basal saurischian dinosaur remains from the Late Triassic, living in India.

Discovery and naming

Alwalkeria was originally named Walkeria maleriensis by

In 2005, Rauhut and Remes found Alwalkeria to be a chimera, with the anterior skull referable to a

Description

The only known specimen,

Dentition and diet

The holotype had

Classification and phylogeny

Chatterjee 1987 originally described Alwalkeria as a basal theropod.

Alwalkeria has not been included in a

Distinguishing anatomical features

A diagnosis is a statement of the anatomical features of an organism (or group) that collectively distinguish it from all other organisms. Some, but not all, of the features in a diagnosis are also autapomorphies. An autapomorphy is a distinctive anatomical feature that is unique to a given organism or group.

According to Chatterjee (1987) Alwalkeria can be distinguished based on the following characteristics:[15]

- an excavation is present in the bases of the dorsal neural arches(debated because the vertebrae likely don't belong to Alwalkeria)

- the presence of a highly expanded femoral head

- the fourth trochanter is very prominent

Several features would make Alwalkeria unique among basal dinosaurs, such as its lack of

Paleoecology

Provenance and occurrence

The only known specimen of Alwalkeria was recovered in the Godavari Valley locality from the Maleri Formation of Andhra Pradesh, India. The remains were collected by S. Chatterjee in 1974 in red mudstone that was deposited during the Carnian stage of the Triassic period, approximately 235 to 228 million years ago. The specimen is housed in the collection of the Indian Statistical Institute, in Kolkata, India.

Fauna and habitat

The Maleri Formation has been interpreted as being the site of an ancient lake or river. Material of the prosauropods Jaklapallisaurus and Nambalia have been found in the Maleri Formation, as well as intermediate prosauropod remains, and Alwalkeria is the only named carnivorous dinosaur species from this locality.

References

- ^ Agnolín, F.L. (2017). "Estudio de los Dinosauromorpha (Reptilia, Archosauria) de la Formación Chañares (Triásico Superior), Provincia de la Rioja, Argentina. Sus implicancias en el origen de los Dinosaurios". D Phil. Thesis, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo.

- ^ Chatterjee, S. & Creisler, B.S. 1994. Alwalkeria (Theropoda) and Morturneria (Plesiosauria), new names for preoccupied Walkeria Chatterjee, 1987, and Turneria Chatterjee and Small, 1989. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 14(1): 142.

- ^ Remes and Rauhut, 2005. The oldest Indian dinosaur Alwalkeria maleriensis Chatterjee revised: a chimera including remains of a basal saurischian. in Kellner, Henriques and Rodrigues (eds). II Congresso Latino-Americano de Paleontologia de Vertebrados, Boletim de Resumos. Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro. 218.

- .

- ^ Langer, M.C. 2004. Basal Saurischia. In: Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., & Osmolska, H. (Eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd Edition). Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 25–46.

- OCLC 985402380.

- S2CID 229651571.

- ^ Chatterjee, S. 1987. A new theropod dinosaur from India with remarks on the Gondwana-Laurasia connection in the Late Cretaceous. In: McKenzie, G.D. (Ed.). Gondwana Six: Stratigraphy, Sedimentology, and Paleontology. Geophysical Monograph 41. Washington, D.C.: American Geophysical Union. Pp. 183–189.

- ^ R. S. Loyal, A. Khosla, and A. Sahni. 1996. Gondwanan dinosaurs of India: affinities and palaeobiogeography. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 39(3):627-638

- ^ Paul, 1988. Predatory dinosaurs of the world. Simon and Schuster, New York. A New York Academy of Sciences Book. 464 pp.

- ^ a b Langer, M.C. 2004. Basal Saurischia. In: Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., & Osmolska, H. (Eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd Edition). Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 25–46.

- ^ R. N. Martínez and O. A. Alcober. 2009. A basal sauropodomorph (Dinosauria: Saurischia) from the Ischigualasto Formation (Triassic, Carnian) and the early evolution of Sauropodomorpha. PLoS ONE 4(2 (e4397)):1-12

- ^ Sereno, P.C. 1999. The evolution of dinosaurs. Science 284: 2137-2147.

- ^ Fraser, N.C., Padian, K., Walkden, G.M., & Davis, A.L.M. 2002. Basal dinosauriform remains from Britain and the diagnosis of the Dinosauria. Palaeontology 45(1): 79-95.

- ^ Chatterjee, S. 1987. A new theropod dinosaur from India with remarks on the Gondwana-Laurasia connection in the Late Cretaceous. In: McKenzie, G.D. (Ed.). Gondwana Six: Stratigraphy, Sedimentology, and Paleontology. Geophysical Monograph 41. Washington, D.C.: American Geophysical Union. Pp. 183–189.

Bibliography

- Remes, K. and Rauhut, O. W. M. 2005. The oldest Indian dinosaur Alwalkeria maleriensis Chatterjee revised: a chimera including remains of a basal saurischian; p. 218 in Kellner, A. W . A., Henriques, D .D. R. and Rodrigues, T. (eds.), II Congresso Latino-Americano de Paleontologie de Vertebrados. Boletim de Resumos. Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro.

- Chatterjee, S. & Creisler, B.S. 1994. Alwalkeria (Theropoda) and Morturneria (Plesiosauria), new names for preoccupied Walkeria Chatterjee, 1987, and Turneria Chatterjee and Small, 1989. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 14(1): 142.

- Norman, D.B. 1990. Problematic Theropods: Coelurosaurs. In: Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P. & Osmolska, H. (Eds.). The Dinosauria (1st Edition). Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 280–305.

External links

- Alwalkeria at Dinosaurier-Info (in German)