Blackbuck

| Blackbuck | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male and two females | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Antilopinae |

| Tribe: | Antilopini |

| Genus: | Antilope |

| Species: | A. cervicapra

|

| Binomial name | |

| Antilope cervicapra | |

| Subspecies | |

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

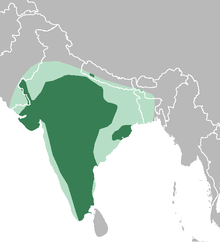

The blackbuck (Antilope cervicapra), also known as the Indian antelope, is a medium-sized antelope native to India and Nepal. It inhabits grassy plains and lightly forested areas with perennial water sources. It stands up to 74 to 84 cm (29 to 33 in) high at the shoulder. Males weigh 20–57 kg (44–126 lb), with an average of 38 kg (84 lb). Females are lighter, weighing 20–33 kg (44–73 lb) or 27 kg (60 lb) on average. Males have 35–75 cm (14–30 in) long corkscrew

are recognized.The blackbuck is

The antelope is native to and occurs mainly in India, while it is

Etymology

The

Taxonomy and evolution

The blackbuck is the sole living member of the genus Antilope and is classified in the

Antilope,

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Two subspecies are recognised,[15][16] although they might be independent species:[17]

- A. c. cervicapra (Linnaeus, 1758), known as the southeastern blackbuck, occurs in southern, eastern, and central India. The white eye ring of the male is narrow above the eye and the neck is all black in the male and the white on the underside is largely restricted to the belly in both males and females. The black leg stripe is well defined and reaches all along the leg.

- A. c. rajputanae Zukowsky, 1927, known as the northwestern blackbuck, occurs in northwestern India. Males have a grey sheen to the dark parts during the breeding season. The white on the underside extends up to half way on the sides of the body and the lower base of the neck of males is white. The white eye ring is broad all around the eye with the leg-stripe going only down to the shanks.

Genetics

The blackbuck shows variation in its diploid

A 1997 study found lower variation in blood

Characteristics

The blackbuck has white fur on the chin and around the eyes, which is in sharp contrast with the black stripes on the face. The coats of males show two-tone colouration; while the upper parts and outsides of the legs are dark brown to black, the underparts and the insides of the legs are all white. Darkness typically increases as the male ages; females and juveniles are yellowish fawn to tan.[21] In Texas, blackbuck moult in spring, following which the males look notably lighter, though darkness persists on the face and the legs.[22] On the contrary, males grow darker as the breeding season approaches.[21] Both melanism[23] and albinism have been observed in wild blackbuck. Albino blackbuck are often zoo attractions as in the Indira Gandhi Zoological Park.[24]

The blackbuck is a moderately sized antelope. It stands up to 74 to 84 cm (29 to 33 in) high at the shoulder; the head-to-body length is nearly 120 cm (47 in).[8] In the population introduced to Texas, males weigh 20–57 kg (44–126 lb), an average of 38 kg (84 lb). Females are lighter, weighing 20–33 kg (44–73 lb) or 27 kg (60 lb) on average.[22] Sexual dimorphism is prominent, as males are heavier and darker than the females.[22] The long, ringed horns, that resemble corkscrews, are generally present only on males, though females may also develop horns. They measure 35–75 cm (14–30 in), though the maximum horn length recorded in Texas has not exceeded 58 cm (23 in). The horns diverge forming a "V"-like shape.[22] In India, horns are longer and more divergent in specimens from the northern and western parts of the country.[16]

Blackbuck bear a close resemblance to gazelles, and are distinguished mainly by the fact that while gazelles are brown in the dorsal parts, blackbuck develop a dark brown or black colour in these parts.[5]

Distribution and habitat

The blackbuck is native to the Indian subcontinent and inhabits grassy plains and thinly forested areas where perennial water sources are available for its daily need to drink. Herds travel long distances to obtain water.[1] The British naturalist

India from the base of the Himalayas to the neighbourhood of

Deccan, but are locally distributed and keep to particular tracts.

Today, small, scattered herds are largely confined to protected areas.[1]

In Pakistan, the blackbuck occasionally occurred along the border with India until 2001.[25] In southern Nepal, the last surviving blackbuck population in Blackbuck Conservation Area was estimated to comprise 184 individuals in 2008.[26] A few blackbucks are present in the

The blackbuck is considered locally extinct in Pakistan and Bangladesh.[1]

Introduced populations

The blackbuck was also introduced into Argentina, numbering about 8,600 individuals as of the early 2000s.[25]

In the early 1900s, blackbuck were introduced to Western Australia.[28] In either the late 1980s or the early 1990s, they were also introduced to Cape York in Far North Queensland, although the population was subsequently eradicated.[28] In 2013, an antelope that appeared to be a blackbuck was sighted at Kakadu National Park in the Northern Territory.[29] In 2015, a blackbuck was sighted near Warrnambool, Victoria, which was later captured and sent to Mansfield Zoo.[30] The blackbuck is a declared pest in Queensland[28] and Western Australia.[31] In Victoria, blackbuck and American bison are considered both "regulated pest animals" and livestock.[32]

The antelope was introduced in Texas in the Edwards Plateau in 1932. By 1988, the population had increased and the antelope was the most populous exotic animal in Texas after the chital.[22][33]

Ecology and behaviour

The blackbuck is a diurnal antelope, though is less active at noon when summer temperatures rise. It can run at a speed of 80 kilometres per hour (50 mph).[8]

Group size fluctuates and seems to depend on the availability of forage and the nature of the habitat. Large herds have an edge over smaller ones in that danger can be detected faster, though individual vigilance is lower in the former. Large herds spend more time feeding than small herds. A disadvantage for large herds, however, is that traveling requires more resources.[34] Herd size reduces in summer.[35]

Males often adopt

The blackbuck is severely affected by natural calamities such as

Blackbucks in Great Indian Bustard Sanctuary show flexible habitat use as the resources and risks change seasonally in the landscape. They use small patches in the area of about 3 km2 (1.2 sq mi). Human activities strongly influenced the movement of herds, but the presence of small refuges allowed them to persist in the landscape.[43]

Diet

The blackbuck is a herbivore and grazes on low grasses, occasionally

Reproduction

Females become

Threats

During the 20th century, blackbuck numbers declined sharply due to excessive hunting,

Until

Conservation

The blackbuck is listed under Appendix III of CITES.[15] In India, hunting of blackbuck is prohibited under Schedule I of the

, including- in Gujarat: Velavadar National Park,Gir Forest National Park;[52]

- in Bihar: Kaimur Wildlife Sanctuary;

- in Maharashtra: Great Indian Bustard Sanctuary;

- in Madhya Pradesh: Kanha National Park[53]

- in Rajasthan: Ranthambhore National Park[54]

- in Karnataka: Ranibennur Blackbuck Sanctuary;

- in Tamil Nadu: Point Calimere Wildlife and Bird Sanctuary,[1] Vallanadu Wildlife Sanctuary,[55] Guindy National Park.

- in Punjab: Abohar Wildlife Sanctuary[55]

A captive population is maintained in Pakistan's Lal Suhanra National Park.[25]

In culture

The blackbuck has associations with the

The animal is mentioned in

In the

The

In some agricultural areas in

In 2018, Bollywood actor Salman Khan, in a high-profile case, was sentenced to five years imprisonment for poaching a blackbuck in 1998.[71]

See also

References

- ^ . Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ a b Palmer, T.S.; Merriam, C.H. (1904). Index Generum Mammalium : A List of the Genera and Families of Mammals. Washington, US: Government Printing Office. pp. 114, 163.

- ^ "Antilope". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ^ "Cervicapra". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-585-19478-3.

- ^ "Blackbuck". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ^ Taylor and Francis. pp. 521−524.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8018-5789-8.

- S2CID 84227895.

- PMID 7608514.

- PMID 10381312.

- S2CID 23227689.

- PMID 23485920.

- ISBN 978-0-471-74398-9.

- ^ OCLC 62265494.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-12. Retrieved 2015-10-01.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4214-0093-8.

- S2CID 27843494.

- S2CID 20620389.

- ^ Schreiber, A.; Fakler, P.; Osterballe, R. (1997). "Blood protein variation in blackbuck (Antilope cervicapra), a lekking gazelle". Zeitschrift für Säugetierkunde. 62 (4): 239–49.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4354-5397-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4773-0886-8. Archived from the originalon 2015-02-22. Retrieved 2016-03-11.

- ^ Smith, J. M. (1904). "Melanism in black buck". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 16: 361.

- ^ Ganguly, N. (11 July 2008). "Albino black buck attracts visitors to zoo". The Hindu. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ^ ISBN 978-2-8317-0594-1.

- .

- ^ "Black Buck IITM campus". Archived from the original on 2018-04-12. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- ^ a b c "Blackbuck antelope". www.business.qld.gov.au. 2016-04-18. Retrieved 2023-10-12.

- ^ "Antelope sightings in Kakadu - ABC (none) - Australian Broadcasting Corporation". www.abc.net.au. Retrieved 2023-10-12.

- ^ "Blackbuck captured in South West". Stock Journal. 2014-08-25. Retrieved 2023-10-12.

- ^ "Antilope cervicapra". www.agric.wa.gov.au. Retrieved 2023-10-12.

- ^ "Interstate livestock movements - Agriculture". Agriculture Victoria. 2023-08-01. Retrieved 2023-10-12.

- ISBN 978-0-520-26421-2.

- S2CID 22424425.

- ^ doi:10.12944/CWE.4.1.18. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2016-03-11. Retrieved 2016-03-11.

- S2CID 32511584.

- S2CID 84513333.

- ^ Rajagopal, T. & Archunan, G. (2006). "Scent marking by Indian blackbuck: Characteristics and spatial distribution of urine, pellet, preorbital and interdigital gland marking in captivity". Wildlife Biodiversity Conservation: Proceedings of the "National Seminar on Wildlife Biodiversity Conservation", 13 to 15 October 2006, A Seminar Conducted During the "bi-decennial Celebrations" of Pondicherry University: 71–80.

- doi:10.1163/156853900502204. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2016-03-11. Retrieved 2016-03-11.

- ^ a b Jhala, Y.V. (1991). Habitat and population dynamics of wolves and blackbuck in Velavadar National Park, Gujarat. Ph.D. dissertation.

- .

- ^ Ranjitsinh, M. K. (1989). The Indian Blackbuck. Dehradun: Natraj Publishers.

- PMID 26985668.

- .

- from the original on 2021-10-25. Retrieved 2019-12-12.

- JSTOR 2405252.

- PMID 23229002.

- PMID 3361506.

- The Tribune. Archivedfrom the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2007-08-24.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-14-306619-4.

- ^ "Schedule I - Wildlife Protection Act" (PDF). moef.nic.in. Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- (PDF) from the original on 2017-08-08. Retrieved 2013-08-25.

- ^ "MP's Kanha park gets its blackbucks back". 19 January 2017. Archived from the original on 6 December 2018. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- CiteSeerX 10.1.1.547.4828.

- ^ a b Joseph, P.P. (2011). "Steps taken to save blackbucks". The Hindu. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- ISBN 978-1-57607-907-2. Archivedfrom the original on 2020-07-27. Retrieved 2023-02-21.

- ISBN 978-90-474-4356-8. Archivedfrom the original on 2020-07-27. Retrieved 2023-02-21.

- ISBN 978-0-674-07280-0.

- ISBN 978-0-8109-0886-4.

- ISBN 978-1-85124-087-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-61091-479-6.

- ^ ISBN 978-90-04-16819-0.

- ^ Vidyarnava, R.B.S.C. (1918). The Sacred Books of the Hindus. Allahabad: Sudhnidra Nath Vasu. p. 5.

- ISBN 978-0-520-20778-3.

- ISBN 978-0-520-21470-5.

- ISBN 978-1-4236-0523-2.

- PMID 5056105.

- .

- ^ Chauhan, N.P.S.; Singh, R. (1990). "Crop damage by overabundant populations of nilgai and blackbuck in Haryana (India) and its management (Paper 13)". Proceedings of the Fourteenth Vertebrate Pest Conference 1990: 218–20. Archived from the original on 2016-10-05. Retrieved 2016-03-11.

- ^ Chauhan, N.P.S.; Sawarkar, V.B. (1989). "Problems of over-abundant populations of 'Nilgai' and 'Blackbuck' in Haryana and Madhya Pradesh and their management". The Indian Forester. 115 (7): 488–493.

- ^ "Blackbuck poaching case: Salman Khan gets 5-year jail term". The Economic Times. 5 April 2018. Archived from the original on 5 April 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

External links

Media related to Antilope cervicapra at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Antilope cervicapra at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Antilope cervicapra at Wikispecies

Data related to Antilope cervicapra at Wikispecies- BBC Nature: Blackbuck