Bovidae

| Bovidae | |

|---|---|

| |

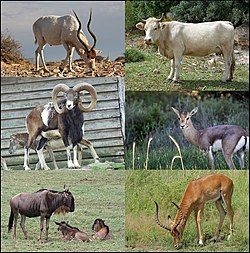

| Example Bovidae (clockwise from top left) – domestic cattle (Bos taurus), mountain gazelle (Gazella gazella), impala (Aepyceros melampus), blue wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus), and mouflon (Ovis gmelini)

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Pecora |

| Superfamily: | Bovoidea |

| Family: | Bovidae Gray, 1821 |

| Type genus | |

| Bos | |

| Subfamilies | |

Alternate taxonomy:

| |

The Bovidae comprise the

The bovids show great variation in size and pelage colouration. Except some domesticated forms, all male bovids have two or more horns, and in many species, females possess horns, too. The size and shape of the horns vary greatly, but the basic structure is always one or more pairs of simple bony protrusions without branches, often having a spiral, twisted or fluted form, each covered in a permanent sheath of keratin. Most bovids bear 30 to 32 teeth.

Most bovids are

The greatest diversities of bovids occur in

Naming and etymology

The name "Bovidae" was given by the British zoologist John Edward Gray in 1821.[1] The word "Bovidae" is the combination of the prefix bov- (originating from Latin bos, "ox", through Late Latin bovinus) and the suffix -idae.[2]

Taxonomy

The

Until the beginning of the 21st century it was understood that the family

Molecular studies have supported

In 1992, Alan W . Gentry of the

A controversy exists about the recognition of

Below is a cladogram based on Yang et al., 2013 and Calamari, 2021:[13][14][15]

| Bovidae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Alternatively, all members of the Aegodontia can be classified within the subfamily Antilopinae, with the individual subfamilies being tribes in this treatment.[14][15]

Evolutionary history

Early Miocene and before

In the early Miocene, bovids began diverging from the

The present genera of Alcelaphinae appeared in the Pliocene. The extinct Alcelaphine genus Paramularius, which was the same in size as the hartebeest, is believed to have come into being in the Pliocene, but became extinct in the middle Pleistocene.[6] Several genera of Hippotraginae are known since the Pliocene and Pleistocene. This subfamily appears to have diverged from the Alcelaphinae in the latter part of early Miocene.[19] The Bovinae are believed to have diverged from the rest of the Bovidae in the early Miocene.[20] The Boselaphini became extinct in Africa in the early Pliocene; their latest fossils were excavated in Langebaanweg (South Africa) and Lothagam (Kenya).[21]

Middle Miocene

The middle Miocene marked the spread of the bovids into China and the Indian subcontinent.

Late Miocene

By the late Miocene, around 10 Mya, the bovids rapidly

Plio-Pleistocene

African bovids continued becoming more adapted to mixed feeding, indicated by dental mesowear evidence, as their palaeoenvironment opened up.[25]

Characteristics

All bovids have the similar basic form - a snout with a blunt end, one or more pairs of horns (generally present on males) immediately after the oval or pointed ears, a distinct neck and limbs, and a tail varying in length and bushiness among the species.[26] Most bovids exhibit sexual dimorphism, with males usually larger as well as heavier than females. Sexual dimorphism is more prominent in medium- to large-sized bovids. All bovids have four toes on each foot – they walk on the central two (the hooves), while the outer two (the dewclaws) are much smaller and rarely touch the ground.[3]

The bovids show great variation in size: the gaur can weigh more than 1,500 kg (3,300 lb), and stand 2.2 m (87 in) high at the shoulder.[27] The royal antelope, in sharp contrast, is only 25 cm (9.8 in) tall and weighs at most 3 kg (6.6 lb).[28] The klipspringer, another small antelope, stands 45–60 cm (18–24 in) at the shoulder and weighs just 10–20 kg (22–44 lb).[29]

Differences occur in

Some species, such as the gemsbok, sable antelope, and Grant's gazelle, are camouflaged with strongly disruptive facial markings that conceal the highly recognisable eye.[35] Many species, such as gazelles, may be made to look flat, and hence to blend into the background, by countershading.[36] The outlines of many bovids are broken up with bold disruptive colouration, the strongly contrasting patterns helping to delay recognition by predators.[37] However, all the Hippotraginae (including the gemsbok) have pale bodies and faces with conspicuous markings. The zoologist Tim Caro describes this as difficult to explain, but given that the species are diurnal, he suggests that the markings may function in communication. Strongly contrasting leg colouration is common only in the Bovidae, where for example Bos, Ovis, bontebok and gemsbok have white stockings. Again, communication is the likely function.[34]

Excepting some domesticated forms, all male bovids have horns, and in many species, females, too, possess horns. The size and shape of the horns vary greatly, but the basic structure is a pair of simple bony protrusions without branches, often having a spiral, twisted, or fluted form, each covered in a permanent sheath of keratin. Although horns occur in a single pair on almost all bovid species, there are exceptions such as the

Male horn development has been linked to

Anatomy

In bovids, the third and fourth

Dentition

Most bovids bear 30 to 32 teeth.

Ecology and behaviour

The bovids have various methods of social organisation and social behaviour, which are classified into solitary and gregarious behaviour. Further, these types may each be divided into territorial and non-territorial behaviour.

Excluding the cephalophines (duikers), tragelaphines (spiral-horned antelopes) and the neotragines, most African bovids are gregarious and territorial. Males are forced to disperse on attaining sexual maturity, and must form their own territories, while females are not required to do so. Males that do not hold territories form bachelor herds. Competition takes place among males to acquire dominance, and fights tend to be more rigorous in limited

Activity

Most bovids are diurnal, although a few such as the buffalo, bushbuck, reedbuck, and grysbok are exceptions. Social activity and feeding usually peak during dawn and dusk. The bovids usually rest before dawn, during midday, and after dark. Grooming is usually by licking with the tongue. Rarely do antelopes roll in mud or dust. Wildebeest and buffalo usually wallow in mud, whereas the hartebeest and topi rub their heads and horns in mud and then smear it over their bodies. Bovids use different forms of vocal, olfactory, and tangible communication. These involve varied postures of neck, head, horns, hair, legs, and ears to convey sexual excitement, emotional state, or alarm. One such expression is the

In the mating season, rutting males bellow to make their presence known to females. Muskoxen roar during male-male fights, and male saigas force air through their noses, producing a roar to deter rival males and attract females. Mothers also use vocal communication to locate their calves if they get separated. During fights over dominance, males tend to display themselves in an erect posture with a level muzzle.[55][56]

Fighting techniques differ amongst the bovid families and also depend on their build. While the hartebeest fight on knees, others usually fight on all fours. Gazelles of various sizes use different methods of combat. Gazelles usually box, and in serious fights may clash and fence, consisting of hard blows from short range. Ibex, goat and sheep males stand upright and clash into each other downwards. Wildebeest use powerful head butting in aggressive clashes. If horns become entangled, the opponents move in a circular manner to unlock them. Muskoxen will ram into each other at high speeds. As a rule, only two bovids of equal build and level of defence engage in a fight, which is intended to determine the superior of the two. Individuals that are evidently inferior to others would rather flee than fight; for example, immature males do not fight with the mature bulls. Generally, bovids direct their attacks on the opponent's head rather than its body. The S-shaped horns, such as those on the impala, have various sections that help in ramming, holding, and stabbing. Serious fights leading to injury are rare.[32][55][57]

Diet

Most bovids alternately feed and ruminate throughout the day. While those that feed on concentrate feed and digest in short intervals, the roughage feeders take longer intervals. Only small species such as the duiker browse for a few hours during day or night.[32] Feeding habits are related to body size; while small bovids forage in dense and closed habitat, larger species feed upon high-fiber vegetation in open grasslands. Subfamilies exhibit different feeding strategies. While Bovinae species graze extensively on fresh grass and diffused forage, Cephalophinae species (with the exception of

Sexuality and reproduction

Most bovids are polygynous. In a few species, individuals are monogamous, resulting in minimal male-male aggression and reduced selection for large body size in males. Thus, sexual dimorphism is almost absent. Females may be slightly larger than males, possibly due to competition among females for the acquisition of territories. This is the case in duikers and other small bovids.[60][61] The time taken for the attainment of sexual maturity by either sex varies broadly among bovids. Sexual maturity may even precede or follow mating. For instance, the impala males, though sexually mature by a year, can mate only after four years of age.[62] On the contrary barbary sheep females may give birth to offspring even before they have gained sexual maturity.[63] The delay in male sexual maturation is more visible in sexually dimorphic species, particularly the reduncines, probably due to competition among males.[3] For instance, the blue wildebeest females become capable of reproduction within a year or two of birth, while the males become mature only when four years old.[31]

All bovids mate at least once a year, and smaller species may even mate twice. Mating seasons occur typically during the rainy months for most bovids. As such, breeding might peak twice in the equatorial regions. The sheep and goats exhibit remarkable seasonality of reproduction, in the determination of which the annual cycle of daily

Lifespan

Most wild bovids live for 10 to 15 years. Larger species tend to live longer;[3] for instance, American bison can live up to 25 years and gaur up to 30 years. The mean lifespan of domesticated individuals is nearly ten years. For example, domesticated goats have an average lifespan of 12 years. Usually males, mainly in polygynous species, have shorter lifespans than females. This can be attributed to several reasons: early dispersal of young males, aggressive male-male fights, vulnerability to predation (particularly when males are less agile, as in kudu), and malnutrition (being large in size, the male body has high nutritional requirements which may not be satisfied).[67][68] Richard Despard Estes suggested that females mimic male secondary sexual characteristics like horns to protect their male offspring from dominant males. This feature seems to have been strongly selected to prevent male mortality and imbalanced sex ratios due to attacks by aggressive males and forced dispersal of young males during adolescence.[69]

Distribution

Most of the diverse bovid species occur in Africa. The maximum concentration is in the

Interaction with humans

Domesticated animals

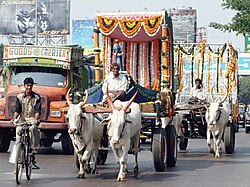

The

The earliest evidence of cattle domestication is from 8000 BC, suggesting that the process began in Cyprus and the Euphrates basin.[70]

Animal products

Bovid

In human culture

Bovidae have featured in stories since at least the time of

References

- OCLC 62265494.

- ^ "Bovidae". Merriam-Webster online dictionary. Archived from the original on 11 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Gomez, W.; Patterson, T. A.; Swinton, J.; Berini, J. "Bovidae: antelopes, cattle, gazelles, goats, sheep, and relatives". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ PMID 12746147.

- PMID 9187090.

- ^ S2CID 29939520.

- ISBN 978-9048-199-624.

- S2CID 86664298.

- ISBN 978-0-306-45471-4.

- ISBN 978-0300-081-428.

- OCLC 62265494.

- OCLC 62265494.

- from the original on 2022-01-31. Retrieved 2022-01-31.

- ^ PMID 10222159.

- ^ from the original on 2023-03-14. Retrieved 2022-02-08.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8160-1194-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8018-7135-1.

- PMID 10603253. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2011-07-20.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-520-25120-5.

- PMID 23339550.

- ISSN 0078-8554.

- ISBN 978-0-226-43724-8.

- ISBN 978-1461-382-737.

- ISBN 978-0300-063-486.

- . Retrieved 2 January 2025 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ ISBN 978-0644-060-561.

- ISBN 978-1-78064-221-5. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-03-14. Retrieved 2021-01-13.

- ^ Huffman, B. "Royal antelope". Ultimate Ungulate. Archived from the original on 16 December 2014. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-7614-7200-1.

- ^ "Oryx leucoryx". The Encyclopedia of Life.

- ^ a b Lundrigan, B.; Bidlingmeyer, J. (2000). "Connochaetes gnou: black wildebeest". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 2013-10-05. Retrieved 2013-08-21.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-520-08085-0.

- S2CID 198123785.

- ^ PMID 18990666.

- ^ Cott, H. B. (1940). Adaptive Coloration in Animals. London: Methuen. pp. 88 and plate 25.

- PMID 21227055.

- ^ Cott, H. B. (1940). Adaptive Coloration in Animals. London: Methuen. p. 53.

- doi:10.1644/843.1.

- ISBN 978-1-58544-555-4.

- American Livestock Breeds Conservancy (2009). "Jacob Sheep". Pittsboro, North Carolina: American Livestock Breeds Conservancy. Archivedfrom the original on 2011-08-10. Retrieved 2011-05-05.

- ^ Bibi, F.; Bukhsianidze, M.; Gentry, A.; Geraads, D.; Kostopoulos, D.; Vrba, E. (2009). "The fossil record and evolution of Bovidae: state of the field". Palaeontologia Electronica. 12 (3): 10A. Archived from the original on 2011-06-16. Retrieved 2010-11-14.

- PMID 1584013.

- JSTOR 1382822.

- S2CID 12030618.

- ^ S2CID 24278541.

- Wikidata Q55899859.

- ^ PMID 19759035.

- S2CID 37000507.

- ISBN 978-0-87196-871-5.

- ISBN 978-0-521-48526-5.

- ^ Ciszek, D. "Bushbuck". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- ^ T. L., Newell. "Waterbuck". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Archived from the original on 28 September 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-521-37024-0.

- hdl:10499/AJ19390.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-07-909508-4.

- ISBN 978-0-7637-6299-5.

- PMID 18006410.

- .

- .

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8018-8695-9. Archivedfrom the original on 2023-03-14. Retrieved 2016-11-07.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-86542-731-0.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-520-08085-0.

- JSTOR 3504009.

- .

- PMID 3413339.

- PMID 12456888.

- S2CID 87280870.

- .

- .

- ISBN 978-0-520-24638-6.

- ^ Phelan, Benjamin; Phelan, Benjamin (24 July 2013). "Others' Milk". Slate.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ISBN 978-1-59373-029-1.

- ^ "Beef, lean organic". WHFoods. 18 October 2004. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ^ "National Bison Association". Bisoncentral.com. Archived from the original on January 20, 2011. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ISBN 978-90-8890-261-1.

- ^ "Merino Sheep in Australia". Archived from the original on 2006-11-05. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ISBN 978-81-269-0810-3.

- JSTOR 24188063.

- ^ "Aesop's Fables". Aesop's Fables. Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ Peck. "Entry:Chimaera". Archived from the original on 11 October 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-415-00228-8.

External links

Media related to Bovidae at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bovidae at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Bovidae at Wikispecies

Data related to Bovidae at Wikispecies- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.