Brazilian battleship São Paulo

São Paulo on its sea trials, 1910

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | São Paulo |

| Namesake | The state and city of São Paulo[1] |

| Builder | Vickers, Barrow-in-Furness, United Kingdom[2] |

| Laid down | 30 April 1907[1][2] |

| Launched | 19 April 1909[1][2] |

| Commissioned | 12 July 1910[1][2] |

| Stricken | 2 August 1947[1][3] |

| Motto | Non Ducor, Duco[1][A] |

| Fate | Sank 1951 while en route to be scrapped |

| General characteristics | |

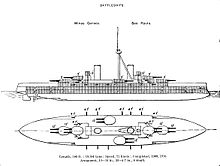

| Class and type | Minas Geraes-class battleship |

| Displacement | |

| Length | |

| Beam | 83 ft (25 m)[5] |

| Draft | |

| Installed power | |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 21.5 knots (39.8 km/h; 24.7 mph)[6] |

| Endurance | 10,000 nautical miles @ 10 knots (11,500 mi @ 11.5 mph or 18,500 km @ 18.5 km/h)[2] |

| Armament | |

| Armour | |

| Notes | Characteristics are as built; cf. Specifications of the Minas Geraes-class battleships |

São Paulo was a dreadnought battleship of the Brazilian Navy. It was the second of two ships in the Minas Geraes class, and was named after the state and city of São Paulo.

The British company

In the 1930s, São Paulo was passed over for modernization due to its poor condition—it could only reach a top speed of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph), less than half its design speed. For the rest of its career, the ship was reduced to a reserve coastal defense role. When Brazil entered the Second World War, São Paulo sailed to

Background

Beginning in the late 1880s, Brazil's navy fell into obsolescence, a situation exacerbated by an

At the turn of the 20th century, soaring demand for

The money authorized for naval expansion was redirected by the new Minister of the Navy, Rear Admiral Alexandrino Fario de Alencar, to building two dreadnoughts, with plans for a third dreadnought after the first was completed, two scout cruisers (which became the Bahia class), ten destroyers (the Pará class), and three submarines.[16][17] The three battleships on which construction had just begun were scrapped beginning on 7 January 1907, and the design of the new dreadnoughts was approved by the Brazilians on 20 February 1907.[15] In South America, the ships came as a shock and kindled a naval arms race among Brazil, Argentina, and Chile. The 1902 treaty between the latter two was canceled upon the Brazilian dreadnought order so both could be free to build their own dreadnoughts.[8]

Minas Geraes, the lead ship, was laid down by Armstrong on 17 April 1907, while São Paulo followed thirteen days later at Vickers.[2][5][18] The news shocked Brazil's neighbors, especially Argentina, whose Minister of Foreign Affairs remarked that either Minas Geraes or São Paulo could destroy the entire Argentine and Chilean fleets.[19] In addition, Brazil's order meant that they had laid down a dreadnought before many of the other major maritime powers, such as Germany, France or Russia,[E] and the two ships made Brazil the third country to have dreadnoughts under construction, behind the United Kingdom and the United States.[11][21]

Newspapers and journals around the world, particularly in Britain and Germany, speculated that Brazil was acting as a proxy for a naval power which would take possession of the two dreadnoughts soon after completion, as they did not believe that a previously insignificant geopolitical power would contract for such powerful warships.[2][22] Despite this, the United States actively attempted to court Brazil as an ally; caught up in the spirit, U.S. naval journals began using terms like "Pan Americanism" and "Hemispheric Cooperation".[2]

Early career

São Paulo was

Revolt of the Lash

Soon after São Paulo's arrival, a major rebellion known as the Revolt of the Lash, or Revolta da Chibata, broke out on four of the newest ships in the Brazilian Navy. The initial spark was provided on 16 November 1910 when

The ships were well-supplied with foodstuffs, ammunition, and coal, and the only demand of mutineers—led by

Humiliated by the revolt, naval officers and the president of Brazil were staunchly opposed to amnesty, so they quickly began planning to assault the rebel ships. The officers believed such an action was necessary to restore the service's honor. The rebels, believing an attack was imminent, sailed their ships out of Guanabara Bay and spent the night of 23–24 November at sea, only returning during daylight. Late on the 24th, the President ordered the naval officers to attack the mutineers. Officers crewed some smaller warships and the cruiser Rio Grande do Sul, Bahia's sister ship with ten 4.7-inch guns. They planned to attack on the morning of the 25th, when the government expected the mutineers would return to Guanabara Bay. When they did not return and the amnesty measure neared passage in the Chamber of Deputies, the order was rescinded. After the bill passed 125–23 and the president signed it into law, the mutineers stood down on the 26th.[37]

During the revolt, the ships were noted by many observers to be well handled, despite a previous belief that the Brazilian Navy was incapable of effectively operating the ships even before being split by a rebellion. João Cândido Felisberto ordered all liquor thrown overboard, and discipline on the ships was recognized as exemplary. The 4.7-inch guns were often used for shots over the city, but the 12-inch guns were not, which led to a suspicion among the naval officers that the rebels were incapable of using the weapons. Later research and interviews indicate that Minas Geraes' guns were fully operational, and while São Paulo's could not be turned after salt water contaminated the

First World War

The Brazilian government declared that the country would be neutral in the

Major refit and the 1920s

São Paulo underwent a refit in New York, beginning on 7 August 1918 and completing on 7 January 1920.

After the refit was completed, São Paulo picked up ammunition in

In 1922, São Paulo and Minas Geraes helped to put down the first of the Tenente revolts. Soldiers seized Fort Copacabana in Rio de Janeiro on 5 July, but no other men joined them. As a result, some men deserted the rebels, and by the next morning only 200 people remained in the fort.[48] São Paulo bombarded the fort, firing five salvos and obtained at least two hits; the fort surrendered half an hour later.[49] The Brazilian Navy's official history reports that one of the hits opened a hole ten meters deep.[24]

Crewmen aboard São Paulo rebelled on 4 November 1924, when First

Late career

In the 1930s, Brazil decided to modernize both São Paulo and Minas Geraes. São Paulo's dilapidated state made this uneconomic; at the time it could sail at a maximum of 10 knots (19 km/h; 12 mph), less than half its design speed.[42] As a result, while Minas Geraes was thoroughly refitted from 1931 to 1938 in the Rio de Janeiro Naval Yard,[29] São Paulo was employed as a coast-defense ship, a role in which it remained for the rest of its service life.[3] During the 1932 Constitutionalist Revolution, it acted as the flagship of a naval blockade of Santos.[29] After repairs in 1934 and 1935, the ship returned to lead three naval training exercises. In the same year, accompanied by the Brazilian cruisers Bahia and Rio Grande do Sul, the Argentine battleships Rivadavia and Moreno, six Argentine cruisers, and a group of destroyers, São Paulo carried the Brazilian President Getúlio Vargas up the River Plate to Buenos Aires to meet with the presidents of Argentina and Uruguay.[1][52]

In 1936, the crew of São Paulo, as well as

As in the First World War, Brazil stayed neutral during the opening years of the

Sinking

After preparing from 5 to 18 September 1951, São Paulo was given an eight-man caretaker crew and taken under tow by two tugs, Dexterous and Bustler, departing Rio de Janeiro on 20 September 1951 for a final voyage to the scrappers.[3][56] When north of the Azores in early November, the flotilla ran into heavy storm seas.[3][29]N

At 17:30 UTC on 4 or 6 November,

On 14 October 1954, the

Footnotes

- ^ The English translation of this Latin phrase is "I am not led, I lead". São Paulo shared this motto with the city the ship was named after.[1]

- ^ Topliss includes specific displacement figures for São Paulo which differ from Minas Geraes.

- Custódio José de Mello, the minister of the navy, revolted against President Floriano Peixoto, bringing nearly all of the Brazilian warships currently in the country with him. Mello's forces took Desterro when the governor surrendered, and began to coordinate with the revolutionaries in Rio Grande do Sul, but loyal Brazilian forces eventually overwhelmed them both. Most of the rebel naval forces were sailed to Argentina, where their crews surrendered; the flagship, Aquidabã, held out near Desterro until sunk by a torpedo boat.[10]

- ^ Chile's naval tonnage was 36,896 long tons (37,488 t), Argentina's 34,425 long tons (34,977 t), and Brazil's 27,661 long tons (28,105 t).[8] For an account of the Argentinian–Chilean naval arms races, see Scheina, Naval History, 45–52.

- ^ Although Germany laid down Nassau two months after Minas Geraes, Nassau was commissioned first.[2][20]

- captain assigned to be the Brazilian government's representative to the mutineers, as "a mullet sliced open for salting."[34]

- ^ cf. Legacy of Pedro II of Brazil.

Endnotes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "E São Paulo," Navios De Guerra Brasileiros.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Scheina, "Brazil," 404.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Whitley, Battleships, 29.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Topliss, "The Brazilian Dreadnoughts," 250.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Topliss, "The Brazilian Dreadnoughts," 249.

- ^ a b c Topliss, "The Brazilian Dreadnoughts," 251.

- ^ Topliss, "The Brazilian Dreadnoughts," 240.

- ^ a b c d e Livermore, "Battleship Diplomacy," 32.

- ^ a b Martins, "Colossos do mares," 75.

- ^ Scheina, Naval History, 67–76, 352.

- ^ a b c Scheina, "Brazil," 403.

- ^ Scheina, Naval History, 80.

- ^ English, Armed Forces, 108.

- ^ Topliss, "The Brazilian Dreadnoughts," 240–245.

- ^ a b Topliss, "The Brazilian Dreadnoughts," 246.

- ^ Scheina, Naval History, 81.

- ^ Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers, "Brazil," 883.

- ^ Scheina, Naval History, 321.

- ^ Martins, "Colossos do mares," 76.

- ^ Campbell, "Germany," 145.

- ^ Whitley, Battleships, 13.

- ^ Martins, "Colossos do mares," 77.

- ^ "Launch Brazil's Battleship," The New York Times, 20 April 1909, 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g "São Paulo I," Serviço de Documentação da Marinha — Histórico de Navios.

- ^ a b c d e Whitley, Battleships, 28.

- ^ "French Criticise Brazil," The New York Times, 25 September 1910, C4.

- ^ "Marshal Hermes Da Fonseca," The Times, 28 September 1910, 4e.

- ^ a b "Keeping Good Order in New Republic," The New York Times, 8 October 1910, 1–2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ribeiro, "Os Dreadnoughts."

- ^ "King Manuel Takes Flight Aboard Brazilian Warship," The Age, 7 October 1910, 7.

- ^ "Europe Stirred By Lisbon News," The Telegraph-Herald, 5 October 1910, 1.

- ^ "The Journey from Lisbon," The Times, 8 October 1910, 5–6a.

- ^ "Movements of Warships," The Times, 8 October 1910, 6a.

- ^ Quoted in Morgan, "The Revolt of the Lash," 41.

- ^ Morgan, "The Revolt of the Lash," 32–38, 50.

- ^ Morgan, "The Revolt of the Lash," 40–42.

- ^ Morgan, "The Revolt of the Lash," 44–46.

- ^ Morgan, "The Revolt of the Lash," 39–40, 48–49, 52.

- ^ Scheina, Latin America's Wars, 35–36.

- ^ Scheina, Latin America's Wars, 37.

- Naval History & Heritage Command, last modified 7 July 2010.

- ^ a b c Whitley, Battleships, 27.

- ^ a b Lind, "Professional Notes," 452.

- ^ Scheina, Latin America, 134.

- ^ Department of Commerce, Reports, 365–66.

- ^ "King Albert and His Queen Sail for Brazil Today," The New York Times, 1 September 1920, 1.

- ^ Whitley, Battleships, 28–29.

- ^ Scheina, Latin America's Wars, 128.

- ^ Poggio, "Um encouraçado contra o forte: 2ª Parte."

- ^ Scheina, Latin America's Wars, 129.

- ^ "Preparing to Take Battleship Home," The Gazette, 12 November 1924, 11.

- ^ "Argentina: Lobsters, Pigeons, Parades," Time, 3 June 1935. (subscription required)

- ^ TORNEIO ABERTO CARIOCA – 1936[permanent dead link] (in Portuguese)

- ^ Scheina, Latin America's Wars, 163–164.

- ^ "Brazilian News and Notes," Brazilian Bulletin 8, no. 185 (1 September 1951): 6.

- ^ "Battleship lost during tow, Inquiry after three years," The Times, 5 October 1954.

- ^ a b "Planes Fail to Find Warship Lost at Sea," Chicago Daily Tribune, 11 November 1951, 27.

- ^ a b "Lost Warship Hunt Given Up," Los Angeles Times, 11 December 1951, 13.

- ^ a b c Hayward, R.F.; Atkinson, A.M.; Nutton, W.J. (14 October 1954). "Wreck Report for 'Sao Paulo', 1951" (PDF). Southampton City Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 24 March 2023.

- ^ "Towed Warship Missing," The New York Times, 9 November 1951, 49.

- ^ "Missing Battleship Located," The New York Times, 16 November 1951, 51.

References

- "Brazil." Journal of the American Society of Naval Engineers 20, no. 3 (1909): 833–836. OCLC 3227025.

- Campbell, N.J.M. "Germany." In Gardiner and Gray, Conway's, 134–189.

- "E São Paulo." Navios De Guerra Brasileiros. Last modified 24 February 2008.

- English, Adrian J. Armed Forces of Latin America. London: Jane's Publishing Inc., 1984. OCLC 11537114.

- Gardiner, Robert and Randal Gray, eds. Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1906–1921. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1985. OCLC 12119866.

- Lind, Wallace L. "Professional Notes." Proceedings of the United States Naval Institute 46, no. 3 (1920): 437–486.

- Livermore, Seward W. "Battleship Diplomacy in South America: 1905–1925." The Journal of Modern History 16, no. 1 (1944): 31–44. OCLC 62219150.

- Martins, João Roberto, Filho. "Colossos do mares [Colossuses of the Seas]." Revista de História da Biblioteca Nacional 3, no. 27 (2007): 74–77. OCLC 61697383.

- Morgan, Zachary R. "The Revolt of the Lash, 1910." In Naval Mutinies of the Twentieth Century: An International Perspective, edited by Christopher M. Bell and Bruce A. Elleman, 32–53. Portland: Frank Cass Publishers, 2003. OCLC 464313205.

- Poggio, Guilherme. "Um encouraçado contra o forte: 2ª Parte [A Battleship against the Strong: Part 2]." n.d. Poder Naval Online. Last modified 12 April 2009.

- Ribeiro, Paulo de Oliveira. "Os Dreadnoughts da Marinha do Brasil: Minas Geraes e São Paulo [The Dreadnoughts of the Brazilian Navy]." Poder Naval Online. Last modified 8 June 2008.

- "São Paulo I." Serviço de Documentação da Marinha – Histórico de Navios. Diretoria do Patrimônio Histórico e Documentação da Marinha, Departamento de História Marítima. Accessed 27 January 2015.

- Scheina, Robert L. "Brazil." In Gardiner and Gray, Conway's, 403–407.

- ———. Latin America: A Naval History 1810–1987. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1987. OCLC 15696006.

- ———. Latin America's Wars. Washington, D.C.: Brassey's, 2003. OCLC 49942250.

- Topliss, David. "The Brazilian Dreadnoughts, 1904–1914." Warship International 25, no. 3 (1988): 240–289. OCLC 1647131.

- OCLC 1777213.

- Villiers, Alan. Posted Missing: The Story of Ships Lost Without a Trace in Recent Years. New York, Charles Scribner's Sons, 1956. Ch. 5: The Battleship Sao Paulo, p. 79-100.

- Whitley, M.J. Battleships of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1998. OCLC 40834665.

Further reading

- Topliss, David (1988). "The Brazilian Dreadnoughts, 1904–1914". Warship International. XXV (3): 240–289. ISSN 0043-0374.

External links

- Slideshow of the battleship on YouTube

- The Brazilian Battleships (Extensive engineering/technical details)