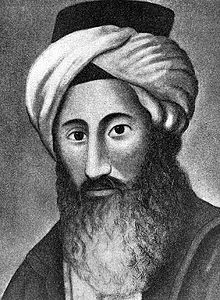

Chaim Yosef David Azulai

Haim Yosef David Azulai | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal | |

| Born | 1724 |

| Died | 1 March 1806 (aged 81–82) |

| Religion | Judaism |

| Children | Raphael Isaiah Azulai, Abraham Azulai |

| Signature |  |

Haim Yosef David Azulai ben Yitzhak Zerachia (1724 – 1 March 1806) (

Some have speculated that his family name, Azulai, is an acronym based on being a Kohen: אשה זנה וחללה לא יקחו (Leviticus, 21:7), a biblical restriction on whom a Kohen may marry.

Biography

Azulai was born in Jerusalem, where he received his education from some local prominent scholars. He was the scion of a prominent rabbinic family, the great-great-grandson of Moroccan Rabbi Abraham Azulai.[2] The Yosef part of his name came from his mother's father, Rabbi Yosef Bialer, a German scholar.[3]

His main teachers were the

In 1755, he was—on the basis of his scholarship—elected to become an emissary (shaliach) for the small Jewish community in the Land of Israel, and he would travel around Europe extensively, making an impression in every Jewish community that he visited. According to some records, he left the Land of Israel three times (1755, 1770, and 1781), living in Hebron in the meantime. His travels took him to Western Europe, North Africa, and—according to legend—to Lithuania, where he met the Vilna Gaon.

In 1755 he was in Germany, where he met the Pnei Yehoshua,[4]

On 28 October 1778 he married, in Pisa, his second wife, Rachel; his first wife, also Rachel, had died in 1773. Noting this event in his diary, he adds the wish that he may be permitted to return to the Land of Israel. This wish seems not to have been realized. In any event, he remained in Leghorn (Livorno), occupied with the publication of his works, and died there twenty-eight years later in 1806 (Friday night, 11 Adar 5566, Shabbat Zachor).[6][3][4] He had been married twice; he had two sons by the names of Abraham and Raphael Isaiah Azulai.

Reburial in Israel

In 1956,[7] the 150th anniversary of Hida's death, Israel's Chief Rabbi Yitzhak Nissim[8]

began work on a plan

His early scholarship

While being a strict Talmudist, and a believer in the Kabbalah, his studious habits and exceptional memory awakened in him an interest in the history of rabbinical literature.

He accordingly began at an early age a compilation of passages in rabbinical literature in which dialectic authors had tried to solve questions that were based on chronological errors. This compilation, which he completed at age 16,[10] he called העלם דבר (Some Oversights); it was never printed.

Azulai's scholarship made him so famous that in 1755 he was chosen as meshulach, (emissary), an honor bestowed on such men only as were, by their learning, well fitted to represent the Holy Land in Europe, where the people looked upon a rabbi from the land of Israel as a model of learning and piety.

Azulai's literary activity is of an astonishing breadth. It encompasses every area of rabbinic literature:

, and literary history. A voracious reader, he noted all historical references; and on his travels he visited the famous libraries of Italy and France, where he examined the Hebrew manuscripts.His works

Azulai was a prolific writer. His works range from a prayerbook he edited and arranged ('Tefillat Yesharim') to a vast spectrum of

Shem HaGedolim

His notes were published in four booklets, comprising two sections, under the titles Shem HaGedolim

Nevertheless, he firmly believed that

Bibliography

A complete bibliographical list of his works is found in the preface to Benjacob's edition of Shem HaGedolim, Vilna, 1852, and frequently reprinted;

- Eliakim Carmoly, in the edition of Shem HaGedolim, Frankfort-on-the-Main, 1843;

- Fuenn, Keneset Yisrael, p. 342;

- Hazan, Hama'alot li-Shelomoh, Alexandria, 1894;

- Aaron Walden, Shem HaGedolim HeChadash, 1879;

- The diary Ma'agal Tob, edited by Elijah Benamozegh, Leghorn, 1879;

- Heimann Joseph Michael, Or ha-chayyim, No. 868.

His role as Shadar

The Hida served the role of

The Hida, like many emissaries, was a qualified and highly regarded personality who was chosen to represent his community. A shadar often had to be able to arbitrate matters of Jewish law for the local Jewish communities Ideally, emissaries were multi-lingual so that they could communicate with both

Moreover, the Hida records numerous instances of miraculous survival and dangerous threats of his day, among them, close scrapes with the

The Hida's intact and published travel diaries, similarly to those of Benjamin of Tudela, provide a comprehensive first hand account of Jewish life and historical events throughout the Europe and Near East of his day.

| Rabbinical eras |

|---|

References

- ^ Paretzky, Zev T. The Chida: Rabbi Chaim Yosef David Azulai: His life and the turbulent times in which he lived. Targum Press, 1998.

- ^ Shem HaGedolim, Livorno 1774, p. 11b. (Available on Hebrewbooks.com.) In this passage, Haim Yosef David gives the following genealogy: Abraham Azulai → Isaac Azualai → Isaiah Azulai → Isaac Zerahiah Azulai → Haim Yosef David Azulai.

- ^ a b "The human side of the Chida". 24 March 2013.

- ^ a b "This Day in History – 11 Adar/March 2". Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ^ An experience Hida described in his Shem HaGeDoLim as "I was fortunate as a young man to spend time with" ... Rabbi Pinches Friedman (12 August 2011). "Shvilei Pinches".

- ^ 'Codex Judaica', Mattis Kantor, p.259

- ^ Dr. Aaron Arend. "You shall carry up my bones from here (Parashat Beshalah 5760/2000)". Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ "Story about the Chida's burial facilitated by Rav Mordechai Eliyahu zt"l". 17 June 2010. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ^ Azoulay, Yehuda (April 2010). "From Italy to Jerusalem". Community Magazine. Brooklyn. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ Mindel, Nissan. "Rabbi Chaim Joseph David Azulai". Kehot Publication Society. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- ^ Cowley, Arthur Ernest (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 176.

- ^ Paretzky, Zev T. The Chida: Rabbi Chaim Yosef David Azulai: His life and the turbulent times in which he lived. Targum Press, 1998.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Azulai, Azulay". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Azulai, Azulay". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls.- Biography of Rabbi Azulai - A Legend of Greatness - The Life & Time of Hacham Haim Yosef David Azoulay by Yehuda Azoulay