Figured bass

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2012) |

Figured bass is

Other systems for

Basso continuo

The makeup of the continuo group is often left to the discretion of the performers (or, for a larger performance, the

Typically performers match the

The keyboard (or other chord-playing instrument) player

Basso continuo, though an essential structural and identifying element of the Baroque period, rapidly declined in the

Figured bass notation

A part notated with figured bass consists of a

The phrase

Composers were inconsistent in the usages described below. Especially in the 17th century, the numbers were omitted whenever the composer thought the chord was obvious. Early composers such as Claudio Monteverdi often specified the octave by the use of compound intervals such as 10, 11, and 15.

Numbers

| Triads | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Inversion | Intervals above bass |

Symbol | Example |

| Root position | 5 3 |

None |  |

| 1st inversion | 6 3 |

6 | |

| 2nd inversion | 6 4 |

6 4 | |

| Seventh chords | |||

| Inversion | Intervals above bass |

Symbol | Example |

| Root position | 7 |  | |

| 1st inversion | 6 5 | ||

| 2nd inversion | 4 3 | ||

| 3rd inversion | 4 2 or 2 | ||

Contemporary figured bass abbreviations for triads and seventh chords are shown in the table to the right.

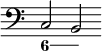

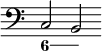

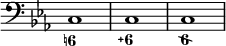

The numbers indicate the number of scale steps above the given bass-line that a note should be played.[4] For example:

Here, the bass note is a C, and the numbers 4 and 6 indicate that notes a fourth and a sixth above it should be played, that is an F and an A. In other words, the second inversion of an F major chord can be realized as:

In cases where the numbers 3 or 5 would normally be understood, these are usually left out. For example:

has the same meaning as

and can be realized as

although the performer may choose which octave to play the notes in and will often elaborate them in some way, such as by playing them as arpeggios rather than as block chords, or by adding improvised ornaments, depending on the tempo and texture of the music.

Sometimes, other numbers are omitted: a 2 on its own or 4

2 indicates , for example. From the figured bass-writer's perspective, this bass note is obviously a

Sometimes the chord changes but the bass note itself is held. In these cases the figures for the new chord are written wherever in the bar they are meant to occur.

- can be realized as

When the bass note changes but the notes in the chord above it are to be held, a line is drawn next to the figure or figures, for as long as the chord is to be held, to indicate this:

- can be realized as

When the bass moves the chord intervals have effectively changed, in this case from 6

3 to 7

4, but no additional numbers are written.

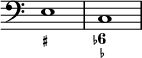

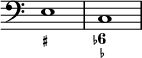

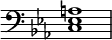

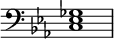

Accidentals

When an accidental is shown on its own without a number, it applies to the note a third above the lowest note; most commonly, this is the third of the chord.[5] Otherwise, if a number is shown, the accidental affects the said interval.[4] For example, this, showing the widespread default meaning of an accidental without number as applying to the third above the bass:

- can be realized as

Sometimes the accidental is placed after the number rather than before it.

Alternatively, a cross placed next to a number indicates that the pitch of that note should be raised (

- can all be realized as

More rarely, a

- can both be realized as

When sharps or flats are used with

Example in context

- J. S. Bach (BWV 443). ⓘ

Contemporary uses

In the 20th and 21st century, figured bass is also sometimes used by

In the 2000s, outside of professional

A form of figured bass is used in notation of accordion music; another simplified form is used to notate guitar chords.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- ^ Schoenberg, Arnold (1983), Structural Functions of Harmony (7th ed.), London: Mcgraw-Hill, pp. 1–2.

- ^ "Classical Era (1750-1820)", TheGreatHistoryofArts.Weebly.com. Accessed: 27 July 2017.

- ^ a b Vigil, R. "Figured Bass Notation" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-10-10. Retrieved July 14, 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-393-95480-7.

- ^ "Reference : Alterations in figured bass".

Further reading

- Schick, Kyle (1 January 2012). "Improvisation: Performer as Co-composer" (PDF). Musical Offerings. 3 (1): 27–35. .

External links

- Figured Bass Symbology Archived 2017-11-20 at the Wayback Machine by Robert Kelley

- Chords that the (major) scale degrees (in the bass) can imply Archived 2017-12-05 at the Wayback Machine by Robert Kelley

- Theory and Practice of the Basso Continuo by Barry Mitchell

- Historical sources on the subject of basso continuo - Viadana, Agazzari etc