Goldberg Variations

The Goldberg Variations (German: Goldberg-Variationen), BWV 988, is a musical composition for keyboard by Johann Sebastian Bach, consisting of an aria and a set of 30 variations. First published in 1741, it is named after Johann Gottlieb Goldberg, who may also have been the first performer of the work.

Composition

The story of how the variations came to be composed comes from an early biography of Bach by Johann Nikolaus Forkel:[1]

[For this work] we have to thank the instigation of the former Russian ambassador to the electoral court of Saxony, Count Kaiserling, who often stopped in Leipzig and brought there with him the aforementioned Goldberg, in order to have him given musical instruction by Bach. The Count was often ill and had sleepless nights. At such times, Goldberg, who lived in his house, had to spend the night in an antechamber, so as to play for him during his insomnia. ... Once the Count mentioned in Bach's presence that he would like to have some clavier pieces for Goldberg, which should be of such a smooth and somewhat lively character that he might be a little cheered up by them in his sleepless nights. Bach thought himself best able to fulfill this wish by means of Variations, the writing of which he had until then considered an ungrateful task on account of the repeatedly similar harmonic foundation. But since at this time all his works were already models of art, such also these variations became under his hand. Yet he produced only a single work of this kind. Thereafter the Count always called them his variations. He never tired of them, and for a long time sleepless nights meant: "Dear Goldberg, do play me one of my variations." Bach was perhaps never so rewarded for one of his works as for this. The Count presented him with a golden goblet filled with 100 Louis d'or. Nevertheless, even had the gift been a thousand times larger, their artistic value would not yet have been paid for.

Forkel wrote his biography in 1802, more than 60 years after the events related, and its accuracy has been questioned. The lack of dedication on the title page also makes the tale of the commission unlikely. Goldberg's age at the time of publication (14 years) has also been cited as grounds for doubting Forkel's tale, although it must be said that he was known to be an accomplished keyboardist and sight-reader. Williams (2001) contends that the Forkel story is entirely spurious.

Arnold Schering has suggested that the aria on which the variations are based was not written by Bach.[citation needed] More recent scholarly literature (such as the edition by Christoph Wolff) suggests that there is no basis for such doubts.

Publication

Rather unusually for Bach's works,[2] the Goldberg Variations were published in his own lifetime, in 1741. The publisher was Bach's friend Balthasar Schmid of Nuremberg. Schmid printed the work by making engraved copper plates (rather than using movable type); thus the notes of the first edition are in Schmid's own handwriting.

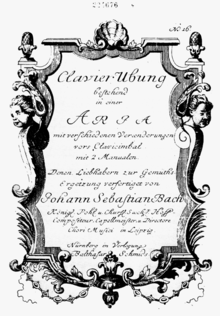

The title page, shown in the figure above, reads in German:

Clavier Ubung / bestehend / in einer ARIA / mit verschiedenen Verænderungen / vors Clavicimbal / mit 2 Manualen. / Denen Liebhabern zur Gemüths- / Ergetzung verfertiget von / Johann Sebastian Bach / Königl. Pohl. u. Churfl. Sæchs. Hoff- / Compositeur, Capellmeister, u. Directore / Chori Musici in Leipzig. / Nürnberg in Verlegung / Balthasar Schmids[3] Keyboard exercise, consisting of an ARIA with diverse variations for harpsichord with two manuals. Composed for connoisseurs, for the refreshment of their spirits, by Johann Sebastian Bach, composer for the royal court of Poland and the Electoral court of Saxony, Kapellmeister and Director of Choral Music in Leipzig. Nuremberg, Balthasar Schmid, publisher.

The term "Clavier Ubung" (nowadays spelled "Klavierübung") had been assigned by Bach to some of his previous keyboard works. Klavierübung part 1 was the six

Nineteen copies of the first edition survive today. Of these, the most valuable is the Handexemplar (Bach's personal copy of the published score),

Instrumentation

On the title page, Bach specified that the work was intended for harpsichord. It is widely performed on this instrument today, though there are also a great number of performances on the piano (see Discography below). The piano was rare in Bach's day and there is no indication that Bach would have either approved or disapproved of performing the variations on this instrument.

Bach's specification is, more precisely, a two-manual harpsichord, and he indicated in the score which variations ought to be played using one hand on each manual: Variations 8, 11, 13, 14, 17, 20, 23, 25, 26, 27 and 28 are specified for two manuals, while variations 5, 7 and 29 are specified as playable with either one or two. With greater difficulty, the work can nevertheless be played on a single-manual harpsichord or piano.

Form

After a statement of the aria at the beginning of the piece, there are thirty variations. The variations do not follow the melody of the aria, but rather use its

The digits above the notes indicate the specified chord in the system of figured bass; where digits are separated by comma (stacked vertically in a proper figured bass), they indicate seventh chords in first inversion.

Every third variation in the series of 30 is a canon, following an ascending pattern. Thus, variation 3 is a canon at the unison, variation 6 is a canon at the second (the second entry begins the interval of a second above the first), variation 9 is a canon at the third, and so on until variation 27, which is a canon at the ninth. The final variation, instead of being the expected canon in the tenth, is a quodlibet, discussed below.

As Kirkpatrick has pointed out,

All the variations are in G major, apart from variations 15, 21, and 25, which are in G minor.

At the end of the thirty variations, Bach writes Aria da Capo e fine, meaning that the performer is to return to the beginning ("da capo") and play the aria again before concluding.

Aria

The aria is a sarabande in 3

4 time, and features a heavily ornamented melody:

![\new PianoStaff <<

\new Staff \relative c''' {

\key g \major \time 3/4

g4 g( a8.)\mordent b16 |

a8 \appoggiatura g16 fis8 \appoggiatura e16 d2 |

g,4\mordent g4.\downprall fis16 g |

a32( g fis16) g32( fis e16) \appoggiatura fis8 d2 |

d'4 d( e8.)\mordent f16 |

e8 \appoggiatura d16 c8 \appoggiatura b16 a4. fis'!8\turn |

g32( fis16.) a32( g16.) fis32( e16.) d32( c16.) \appoggiatura c a'8. c,16 |

b32( g16.) fis8 \appoggiatura fis g2\mordent |

}

\new Staff <<

\new Voice \relative c' {

\voiceOne \clef bass \key g \major

s4 f\rest d |

s4 e\rest d |

s4 d\rest cis |

s4 d\rest a |

s4 d\rest g, |

s4 d'\rest a |

r8 c~ c b16 a g fis e fis |

g8 a b2 |

}

\new Voice \relative c' {

\voiceThree

r4 b2 |

r4 a2 |

r4 g2 |

r4 fis2 |

r4 d2 |

r4 e4. s8 |

}

\new Voice \relative c' {

\voiceTwo

g2. |

fis2. |

e2. |

d2~ d8 c |

b2. |

c2~ c8 d |

e8 c d2 |

g,4. d'8[ e8.^\mordent fis16] |

}

>>

>>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/3/4/34mwxa3i2iviqshel6dphsfz8tyhnjx/34mwxa3i.png)

The French style of ornamentation suggests that the ornaments are supposed to be parts of the melody; however, some performers (for example Wilhelm Kempff on piano) omit some or all ornaments and present the aria unadorned.

Variatio 1. a 1 Clav.

This sprightly variation contrasts markedly with the slow, contemplative mood of the aria. The rhythm in the right hand forces the emphasis on the second beat, giving rise to syncopation from bars 1 to 7. Hands cross at bar 13 from the upper register to the lower, bringing back this syncopation for another two bars. In the first two bars of the B part, the rhythm mirrors that of the beginning of the A part, but after this a different idea is introduced.

Williams sees this as a sort of

Variatio 2. a 1 Clav.

This is a simple three-part contrapuntal piece in 2

4 time, two voices engage in constant motivic interplay over an incessant bass line. Each section has an alternate ending to be played on the first and second repeat.

Variatio 3. Canone all'Unisono. a 1 Clav.

The first of the regular canons, this is a canon at the unison: the follower begins on the same note as the leader, a bar later. As with all canons of the Goldberg Variations (except the 27th variation, canon at the ninth), there is a supporting bass line. The time signature of 12

8 and the many sets of triplets suggest a kind of a simple dance.

Variatio 4. a 1 Clav.

Like the

Each repeated section has alternate endings for the first or second time.

Variatio 5. a 1 ô vero 2 Clav.

This is the first of the hand-crossing, two-part variations; the title means "for one or two manuals".[8] The movement is written in 3

4 time. A rapid melodic line predominantly in sixteenth notes is accompanied by another melody with longer note values, which features very wide leaps:

The Italian type of hand-crossing such as is frequently found in the sonatas of Scarlatti is employed here, with one hand constantly moving back and forth between high and low registers while the other hand stays in the middle of the keyboard, playing the fast passages.

Variatio 6. Canone alla Seconda. a 1 Clav.

The sixth variation is a canon at the second: the follower starts a major second higher than the leader. The piece is based on a descending scale and is in 3

8 time. Kirkpatrick describes this piece as having "an almost nostalgic tenderness". Each section has an alternate ending to be played on the first and second repeat.

Variatio 7. a 1 ô vero 2 Clav. al tempo di Giga

The variation is in 6

8 meter, suggesting several possible Baroque dances. In 1974, when scholars discovered Bach's own copy of the first printing of the Goldberg Variations, they noted that over this variation Bach had added the heading al tempo di

He concludes, "It need not go quickly." Moreover, Schulenberg adds that the "numerous short

The pianist

Variatio 8. a 2 Clav.

This is another two-part hand-crossing variation, in 3

4 time. The French style of hand-crossing such as is found in the clavier works of François Couperin is employed, with both hands playing at the same part of the keyboard, one above the other. This is relatively easy to perform on a two-manual harpsichord, but quite difficult to do on a piano.

Most bars feature either a distinctive pattern of eleven sixteenth notes and a sixteenth rest, or ten sixteenth notes and a single eighth note. Large leaps in the melody occur. Both sections end with descending passages in thirty-second notes.

Variatio 9. Canone alla Terza. a 1 Clav.

This is a canon at the third, in 4

4 time. The supporting bass line is slightly more active than in the previous canons.

Variatio 10. Fughetta. a 1 Clav.

Variation 10 is a four-voice fughetta, with a four-bar subject heavily decorated with ornaments and somewhat reminiscent of the opening aria's melody.

The exposition takes up the whole first section of this variation (pictured). First the subject is stated in the bass, starting on the G below middle C. The answer (in the tenor) enters in bar 5, but it's a tonal answer, so some of the intervals are altered. The soprano voice enters in bar 9, but only keeps the first two bars of the subject intact, changing the rest. The final entry occurs in the alto in bar 13. There is no regular counter-subject in this fugue.

The second section develops using the same thematic material with slight changes. It resembles a counter-exposition: the voices enter one by one, all begin by stating the subject (sometimes a bit altered, like in the first section). The section begins with the subject heard once again, in the soprano voice, accompanied by an active bass line, making the bass part the only exception since it doesn't pronounce the subject until bar 25.

Variatio 11. a 2 Clav.

This is a virtuosic two-part toccata in 12

16 time. Specified for two manuals, it is largely made up of various scale passages, arpeggios and trills, and features much hand-crossing of different kinds.

Variatio 12. a 1 Clav. Canone alla Quarta in moto contrario

This is a canon at the fourth in 3

4 time, of the inverted variety: the follower enters in the second bar in

In the first section, the left hand accompanies with a bass line written out in repeated quarter notes, in bars 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, and 7. This repeated note motif also appears in the first bar of the second section (bar 17, two Ds and a C), and, slightly altered, in bars 22 and 23. In the second section, Bach changes the mood slightly by introducing a few appoggiaturas (bars 19 and 20) and trills (bars 29–30).

Variatio 13. a 2 Clav.

This variation is a slow, gentle and richly decorated sarabande in 3

4 time. Most of the melody is written out using thirty-second notes, and ornamented with a few appoggiaturas (more frequent in the second section) and a few mordents. Throughout the piece, the melody is in one voice, and in bars 16 and 24 an interesting effect is produced by the use of an additional voice. Here are bars 15 and 16, the ending of the first section (bar 24 exhibits a similar pattern):

![\new PianoStaff <<

\new Staff \relative c'' {

\key g \major \time 3/4

cis32 g fis g a g fis g e' cis b cis d cis b cis g' e d e a g fis e |

<< { fis16 cis cis d d g, g fis fis4 } \\ { s4 r8 cis d4 } >> | \bar ":|."

}

\new Staff <<

\new Voice \relative c' {

\key g \major \clef bass \voiceOne

a8[ cis] g' e cis4 |

d8[ e,] f bes a4 |

}

\new Voice \relative c {

\voiceTwo

a8 a'16. g32 a4. a8 |

d,2. |

}

>>

>>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/7/g/7g4o1fvl96j21d7rnjzxk6n3px56x4t/7g4o1fvl.png)

Variatio 14. a 2 Clav.

This is a rapid two-part hand-crossing toccata in 3

4 time, with many trills and other ornamentation. It is specified for two manuals and features large jumps between registers. Both features (ornaments and leaps in the melody) are apparent from the first bar: the piece begins with a transition from the G two octaves below middle C, with a lower mordent, to the G two octaves above it with a trill with initial turn.

Bach uses a loose inversion motif between the first half and the second half of this variation, "recycling" rhythmic and melodic material, passing material that was in the right hand to the left hand, and loosely (selectively) inverting it.

Contrasting it with Variation 15, Glenn Gould described this variation as "certainly one of the giddiest bits of neo-Scarlatti-ism imaginable."[10]

Variatio 15. Canone alla Quinta. a 1 Clav.: Andante

This is a canon at the fifth in 2

4 time. Like Variation 12, it is in contrary motion with the leader appearing inverted in the second bar. This is the first of the three variations in G minor, and its melancholic mood contrasts sharply with the playfulness of the previous variation. Pianist Angela Hewitt notes that there is "a wonderful effect at the very end [of this variation]: the hands move away from each other, with the right suspended in mid-air on an open fifth. This gradual fade, leaving us in awe but ready for more, is a fitting end to the first half of the piece."

Glenn Gould said of this variation, "It's the most severe and rigorous and beautiful canon ... the most severe and beautiful that I know, the canon in inversion at the fifth. It's a piece so moving, so anguished—and so uplifting at the same time—that it would not be in any way out of place in the St. Matthew's Passion; matter of fact, I've always thought of Variation 15 as the perfect Good Friday spell."[10]

Variatio 16. Ouverture. a 1 Clav.

The entire set of variations can be seen as being divided into two halves, clearly marked by this grand French overture, commencing with particularly emphatic opening and closing

Variatio 17. a 2 Clav.

This variation is another two-part virtuosic toccata. Peter Williams sees echoes of Antonio Vivaldi and Domenico Scarlatti here. Specified for two manuals, the piece features hand-crossing. It is in 3

4 time and usually played at a moderately fast tempo. Rosalyn Tureck is one of the very few performers who recorded slow interpretations of the piece. In making his 1981 re-recording of the Goldberg Variations, Glenn Gould considered playing this variation at a slower tempo, in keeping with the tempo of the preceding variation (Variation 16), but ultimately decided not to because "Variation 17 is one of those rather skittish, slightly empty-headed collections of scales and arpeggios which Bach indulged when he wasn't writing sober and proper things like fugues and canons, and it just seemed to me that there wasn't enough substance to it to warrant such a methodical, deliberate, Germanic tempo."[10]

Variatio 18. Canone alla Sesta. a 1 Clav.

This is a canon at the sixth in 2

2 time. The canonic interplay in the upper voices features many

Variatio 19. a 1 Clav.

This is a dance-like three-part variation in 3

8 time. The same sixteenth note figuration is continuously employed and variously exchanged between each of the three voices. This variation incorporates the rhythmic model of variation 13 (complementary exchange of quarter and sixteenth notes) with variations 1 and 2 (syncopations).[12]

Variatio 20. a 2 Clav.

This variation is a virtuosic two-part toccata in 3

4 time. Specified for two manuals, it involves rapid hand-crossing. The piece consists mostly of variations on the texture introduced during its first eight bars, where one hand plays a string of eighth notes and the other accompanies by plucking sixteenth notes after each eighth note. To demonstrate this, here are the first two bars of the first section:

Variatio 21. Canone alla Settima

The second of the three minor key variations, variation 21 has a tone that is somber or even tragic, which contrasts starkly with variation 20.

4 time; Kenneth Gilbert sees it as an allemande despite the lack of anacrusis.[14] The bass line begins the piece with a low note, proceeds to a slow lament bass

A similar pattern, only a bit more lively, occurs in the bass line in the beginning of the second section, which begins with the opening motif inverted.

Variatio 22. a 1 Clav. alla breve

This variation features four-part writing with many imitative passages and its development in all voices but the bass is much like that of a fugue. The only specified ornament is a trill which is performed on a whole note and which lasts for two bars (11 and 12).

The

Variatio 23. a 2 Clav.

Another lively two-part virtuosic variation for two manuals, in 3

4 time. It begins with the hands chasing one another, as it were: the melodic line, initiated in the left hand with a sharp striking of the G above middle C, and then sliding down from the B one octave above to the F, is offset by the right hand, imitating the left at the same pitch, but a quaver late, for the first three bars, ending with a small flourish in the fourth:

This pattern is repeated during bars 5–8, only with the left hand imitating the right one, and the scales are ascending, not descending. We then alternate between hands in short bursts written out in short note values until the last three bars of the first section. The second section starts with this similar alternation in short bursts again, then leads to a dramatic section of alternating thirds between hands. Williams, marvelling at the emotional range of the work, asks: "Can this really be a variation of the same theme that lies behind the adagio no 25?"[This quote needs a citation]

Variatio 24. Canone all'Ottava. a 1 Clav.

This variation is a canon at the octave, in 9

8 time. The leader is answered both an octave below and an octave above; it is the only canon of the variations in which the leader alternates between voices in the middle of a section. [citation needed]

Variatio 25. a 2 Clav.: Adagio

Variation 25 is the third and last variation in G minor; it is marked

4 time. The melody is written out predominantly in sixteenth and thirty-second notes, with many chromaticisms

Variatio 26. a 2 Clav.

In sharp contrast with the introspective and passionate nature of the previous variation, this piece is another virtuosic two-part toccata, joyous and fast-paced. Underneath the rapid arabesques, this variation is basically a sarabande.[14] Two time signatures are used, 18

16 for the incessant melody written in sixteenth notes and 3

4 for the accompaniment in quarter and eighth notes; during the last five bars, both hands play in 18

16.

Variatio 27. Canone alla Nona. a 2 Clav.

Variation 27 is the last canon of the piece, at the ninth and in 6

8 time. This is the only canon where two manuals are specified not due to hand-crossing difficulties, and the only pure canon of the work, because it does not have a bass line.

Variatio 28. a 2 Clav.

This variation is a two-part toccata in 3

4 time that employs a great deal of hand crossing. Trills are written out using thirty-second notes and are present in most of the bars. The piece begins with a pattern in which each hand successively picks out a melodic line while also playing trills. Following this is a section with both hands playing in contrary motion in a melodic contour marked by sixteenth notes (bars 9–12). The end of the first section features trills again, in both hands now and mirroring one another:

The second section starts and closes with the contrary motion idea seen in bars 9–12. Most of the closing bars feature trills in one or both hands.

Variatio 29. a 1 ô vero 2 Clav.

This variation consists mostly of heavy chords alternating with sections of brilliant arpeggios shared between the hands. It is in 3

4 time. A rather grand variation, it adds an air of resolution after the lofty brilliance of the previous variation. Glenn Gould states that variations 28 and 29 present the only case of "motivic collaboration or extension between successive variations."

Variatio 30. a 1 Clav. Quodlibet

The final variation is titled after the quodlibet tradition, in which multiple popular songs are played at once or in succession. According to Forkel, the many musicians of the Bach family practiced this tradition at gatherings:

As soon as they were assembled a chorale was first struck up. From this devout beginning they proceeded to jokes which were frequently in strong contrast. That is, they then sang popular songs partly of comic and also partly of indecent content, all mixed together on the spur of the moment. ... This kind of improvised harmonizing they called a Quodlibet, and not only could laugh over it quite whole-heartedly themselves, but also aroused just as hearty and irresistible laughter in all who heard them.

Though Bach never noted the sources of Variation 30,[19] Forkel's anecdote led to the belief that it is composed from German Volkslied melodies, as if to evoke the Bach gatherings.[20]

Since folk tunes commonly shared melodies, music alone does not identify the songs intended.[21] For example, part of Variation 30 traces back to the melody of the Italian Bergamask dance,[19] which not only gave rise to compositions by many musicians (such as Dieterich Buxtehude, under the title of La Capricciosa, for his thirty-two partite in G major, BuxWV 250[22]), but is even sung to various words in regions such as Iceland today.[23]

A handwritten note found in a collector's copy of the Clavier Ubung claims that Bach's student, Johann Christian Kittel, identified two folk tunes making up Variation 30 by their first lines. Siegfried Dehn of the Prussian royal library later appended purported full texts to this note:

- Ich bin solang nicht bei dir g'west, ruck her, ruck her ("I have so long been away from you, come closer, come closer") and

- Kraut und Rüben haben mich vertrieben, hätt mein' Mutter Fleisch gekocht, wär ich länger blieben ("Cabbage and turnips have driven me away, had my mother cooked meat, I'd have opted to stay"), ascribed to the Bergamask theme.[24]

Dehn's texts, though unsourced, stand as the only historical evidence for the provenance of Bach's Quodlibet and are commonly quoted. Today, the identity of "Kraut und Rüben..." is uncontroversial, since multiple versions of the text, including some explicitly set to the Bergamask theme, are preserved.[19] In contrast, the "Ich bin solang..." text is much more obscure,[25] and these words have not been found in any Volkslied archives.[19]

Other bars of Variation 30 can be heard as incipits of yet more songs, though none have been identified.[26]

Aria da Capo

A note-for-note repeat of the aria at the beginning. Williams writes that the work's "elusive beauty ... is reinforced by this return to the Aria. ... no such return can have a neutral

Canons on the Goldberg ground, BWV 1087

When Bach's personal copy of the printed edition of the Goldberg Variations (see above) was discovered in 1974, it was found to include an appendix in the form of fourteen canons built on the first eight bass notes from the aria. It is speculated that the number 14 refers to the ordinal values of the letters in the composer's name: B(2) + A(1) + C(3) + H(8) = 14.[28] Among those canons, the eleventh and the thirteenth are first versions of BWV 1077 and BWV 1076; the latter is included in the famous portrait of Bach painted by Elias Gottlob Haussmann in 1746.[29]

Transcribed and popularized versions

The Goldberg Variations has been reworked freely by many performers, changing either the instrumentation, the notes, or both. The Italian composer Busoni prepared a greatly altered transcription for piano. According to the art critic Michael Kimmelman, "Busoni shuffled the variations, skipping some, then added his own rather voluptuous coda to create a three-movement structure; each movement has a distinct, arcing shape, and the whole becomes a more tightly organized drama than the original."[30] Other arrangements include:

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2022) |

- 1883: Josef Rheinberger, transcription (tr.) for two pianos, Op. 3 (rev. Max Reger)

- 1912: Karl Eichler, tr. for piano four hands

- 1938: Józef Koffler, tr. for orchestra / string orchestra

- 1975: Charles Ramirez and Helen Kalamuniak, tr. for two guitars

- 1982: Lynn Harting-Ware, aria and variations 1, 2, 4, 13, 19, 9, 7, 15, 27, and 30 for guitar (in the order she plays them on her Forest Scenes album).[31]

- 1984: Dmitry Sitkovetsky, tr. for string trio (rev. in 2009; he also made an arrangement for string orchestra in 1992)

- 1987: Jean Guillou, tr. for organ

- 1988: Joel Spiegelman, tr. for Kurzweil 250 Digital Synthesizer

- 1996: Kurt Rodarmer, tr. for guitar

- 1997: József Eötvös, tr. for guitar

- 1999 (at the latest): Bernard Labadie tr. for string orchestra and continuo

- 2000: Jacques Loussier, arrangement (arr.) for jazz trio

- 2000: Uri Caine, arr. for various ensembles

- 2003: Karlheinz Essl, Gold.Berg.Werk, arr. for string trio and live electronics[32]

- 2009: Catrin Finch, complete tr. for harp

- 2010: David Maslanka, tr. for saxophone quartet

- 2010: Federico Sarudiansky, arr. for string trio (violin, viola, cello)

- 2011: James Strauss, complete tr. for flute and harpsichord/flute and piano

- 2011: Dan Tepfer, Goldberg Variations/Variations,[33] each original variation followed by a jazz improvisation based on that variation

- 2012: Karlheinz Essl, Gold.Berg.Werk arr. for piano, transducer and live-electronics[32]

- 2012: François Meïmoun, arr. for string quartet

- 2016: Mika Pohjola, arr. for piano, harpsichord and string quartet

- 2017: Rinaldo Alessandrini and Concerto Italiano, Variations on Variations, arr. for ensemble[34]

- 2018: Caio Facó, orchestration for chamber orchestra

- 2018: Marcela Mendez and Maria Luisa Rayan, tr. for two harps

- 2020: Parker Ramsay, Bach: Goldberg Variations (arranged for harp)

Editions of the score

- Ralph Kirkpatrick. New York/London: G. Schirmer, 1938. Contains an extensive preface by the editor and a facsimile of the original title page.

- Hans Bischoff. New York: Edwin F. Kalmus, 1947 (editorial work dates from the nineteenth century). Includes interpretive markings by the editor not indicated as such.

- Christoph Wolff. Vienna: Wiener Urtext Edition, 1996. An urtext edition, making use of the new findings (1975) resulting from the discovery of an original copy hand-corrected by the composer. Includes suggested fingerings and notes on interpretation by the harpsichordist Huguette Dreyfus.

- Reinhard Böß. München: edition ISBN 3-88377-523-1Edition of the canons in BWV 1087 only. The editor suggests a complete complement of all fourteen canons.

- Werner Schweer, 2012. The Goldberg Variations, MuseScore Edition created for the Open Goldberg Variations Project and released as public domain. Available online at MuseScore.com

See also

- Goldberg Variations discography

- Goldberg Variations, a satirical play by George Tabori

Notes

- ^ Translation from Kirkpatrick 1938, p. vii.

- ^ See List of compositions by Johann Sebastian Bach printed during his lifetime

- ^ Kirkpatrick 1938, p. vii

- Neue Bach-Ausgabe and the Bach-Werke-Verzeichnisdo refer to the variations as "Klavierübung IV".

- ^ Wolff 1976.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 1938

- ^ Kirkpatrick 1938, p. viii

- ^ The Italian usage is somewhat archaic; for details see Wiktionary entry: [1]

- ^ Schulenberg 2006, p. 380.

- ^ a b c d Gould & Page 2002

- ^ Kenyon, Nicholas. The Faber Pocket Guide to Bach, p. 421 (Faber & Faber, 2011).

- ^ Melamed, Daniel. Bach Studies 2, p. 67 (Cambridge University Press 2006).

- ^ a b Lederer, Victor. Bach's Keyboard Music, p. 121 (Hal Leonard Corporation, 2010).

- ^ a b Notes to Kenneth Gilbert's recording of the variations.

- ^ Tomita, Yo. "The "Goldberg" Variations, Essay by Yo Tomita (1997)". Qub.ac.uk. Retrieved 2012-08-11.

- ISBN 978-1-4422-3064-4.

- ^ Williams 2001, p. 82.

- ^ Gould, Glenn (1956). Bach: The Goldberg Variations (liner notes). Columbia Records.

- ^ a b c d Combet, Jean-Paul (2001). Variations Goldberg (booklet). Céline Frisch. Paris: Alpha Productions. Alpha 014.

- ^ Kirkpatrick 1938, p. viii

- ^ Williams 2001, p. 90.

- ^ Schulenberg 2006, p. 387.

- ^ Allen, David (October 20, 2023). "The Pianist Vikingur Olafsson on 'History's Greatest Keyboard Work'". The New York Times. Retrieved 2024-04-23.

- ^ Marissen, Michael (Fall–Winter 2021). "The Serious Nature of the Quodlibet in Bach's 'Goldberg Variations'" (PDF). CrossAccent. Valparaiso, Indiana: Association of Lutheran Church Musicians. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- ^ Ólafsson, Víkingur (2023). Goldberg Variations (booklet). Víkingur Ólafsson. Berlin: Deutsche Grammophon. 486 4553.

- ^ Williams 2001, p. 89.

- ^ Williams 2001, p. 92.

- ^ See chapter 7 of Richard Taruskin (2009) Music in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries: The Oxford History of Western Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Extract viewable at Google Books.

- ^ "Fourteen Canons on the First Eight Notes of the Goldberg Ground (BWV 1087)". Jan.ucc.nau.edu. Retrieved 2012-08-11.

- ^ Kimmelman, Michael (January 4, 1998). "Exploring Busoni, As Anchored by Bach Or Slightly at Sea". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-08-11.

- OCLC 70600140

- ^ a b "Gold.Berg.Werk", essl.at

- ^ Margasak, Peter (29 November 2011). "Dan Tepfer's "Goldberg Variations"". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ Freeman-Attwood, Jonathan. "JS BACH: Variations on Variations". Gramophone. Retrieved 2018-04-20.

Sources

- Gould, Glenn and Page, Tim (2002). A State of Wonder, disc 3. Sony.

- ISBN 978-0-7935-2245-3.

- Schulenberg, David (2006). The Keyboard Music of J. S. Bach. New York and Oxford: Routledge. pp. 369–388. ISBN 0-415-97400-3.

- ISBN 0-521-00193-5.

- JSTOR 831018.

Further reading

- ISBN 3-89487-352-3. An English translation was published by Da Capo Press in 1970.

- Niemüller, Heinz Hermann (1985). "Polonaise und Quodlibet: Der innere Kosmos der Goldberg-Variationen" in Johann Sebastian Bach: Goldberg Variationen, Musik-Konzepte 42 (Kassel: Bärenreiter), pp. 3–28, esp. 22–26.

- Schiassi, Germana (2007). Johann Sebastian Bach. Le Variazioni Goldberg. Bologna: Albisani Editore. ISBN 978-88-95803-00-5.

- Fiore, Carlo (2009). Bach Goldberg Beethoven Diabelli. Palermo: L'Epos. ISBN 978-8883023996.

- Velikovskiy, Alexander (2021). Goldberg Variations by J.S. Bach. Saint Petersburg: Planeta Musiki ISBN 978-5-8114-6876-8. [in Russian]

- Kennicott, Philip, Counterpoint: a Memoir of Bach and Mourning, WW Norton & Company, New York, 2020, ISBN 978-0-393-86838-8

External links

- Goldberg Week at NPR's Deceptive Cadence

- Video showing how the fifth canon of BWV 1087 can be written on a clear Mobius strip

Online scores

- Goldberg Variations: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Goldberg Variations on Mutopia

- Animated graphical scores of the Goldberg Variations, with harpsichord performances by Colin Booth

Essays

- "Goldberg Variations – The Best Recordings" – theclassicreview.com

- The Goldberg Variations made new – Review of Glenn Gould's and Simone Dinnerstein's renditions

- An essay on the Goldberg Variations by Yo Tomita

- Canons of the Goldberg Variations – graphical analysis enables you to see the leader and follower in the canons

- J.S. Bach, the architect and servant of the spiritual – a closer look at the Goldberg Variations

Recordings

- Public-domain piano recording by Kimiko Ishizaka(Open Goldberg Variations project), with linked newly edited score.

- Bach-cantatas.com: The Goldberg Variations – Comprehensive discography

- jsbach.org: BWV 988 – Reviews of many recordings