Halo (religious iconography)

A halo (from

Halos may be shown as almost any colour or combination of colours, but are most often depicted as golden, yellow or white (when representing light) or as red (when representing flames). The earliest artistic depictions of halos were probably in

Ancient Mesopotamia and Persia

Sumerian religious literature frequently speaks of melam (melammu in Akkadian), a "brilliant, visible glamour which is exuded by gods, heroes, sometimes by kings, and also by temples of great holiness and by gods' symbols and emblems."[5]

Ancient Greek world

Asian art

In India, the use of halo might date back to the second half of the second millennium BC. Two figures appliqued on a pottery vase fragment from

In Chinese and Japanese

In India the head halo is called Prabhamandala or Siras-cakra, while the full body halo is Prabhavali. did not use the halo for many centuries, but later adopted it, though less thoroughly than other religious groups.

In Asian art, the nimbus is often imagined as consisting not just of light, but of flames. This type seems to first appear in Chinese bronzes of which the earliest surviving examples date from before 450.

Halos are found in

Egypt and Asia

-

Ra with solar disc, before 1235 BC

-

The KushanBuddha and Indra

-

Northern Wei Buddhist bronze, 524, with two-ringed halo within a flaming mandorla

-

Hindufigure (11th century)

-

TheMughal emperor Jahangiroften had himself depicted with a halo of unprecedented size. c. 1620.

-

ModernHindu devotional images of Durgaand other haloed deities

Roman art

The halo represents an

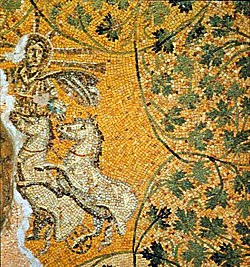

In a late 2nd century AD floor mosaic from Thysdrus,

Christian art

The halo was incorporated into

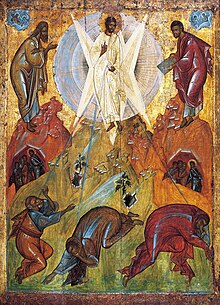

A cruciform halo, that is to say a halo with a cross within, or extending beyond, the circle is used to represent the persons of the

In

Later, triangular haloes are sometimes given to God the Father to represent the Trinity.[32] When he is represented by a hand emerging from a cloud, this may be given a halo.

Plain round haloes are typically used to signify

Beatified figures, not yet canonised as saints, are sometimes shown in medieval Italian art with linear rays radiating out from the head, but no circular edge of the nimbus defined; later this became a less obtrusive form of halo that could be used for all figures.[34] Mary has, especially from the Baroque period onwards, a special form of halo in a circle of twelve stars, derived from her identification as the Woman of the Apocalypse.

Square haloes were sometimes used for the living in

Personifications of the

The whole-body image of radiance is sometimes called the '

Where gold is used as a background in miniatures, mosaics and panel paintings, the halo is often formed by inscribing lines in the gold leaf, and may be decorated in patterns (diapering) within the outer radius, and thus becomes much less prominent. The gold leaf inside the halo may also be burnished in a circular manner, so as to produce the effect of light radiating out from the subject's head. In the early centuries of its use, the Christian halo may be in most colours (though black is reserved for Judas, Satan and other evil figures) or multicoloured; later gold becomes standard, and if the entire background is not gold leaf, the halo itself usually will be.[42]

Decline of the halo

With increasing

In the early 15th century Jan van Eyck and Robert Campin largely abandoned their use, although some other Early Netherlandish artists continued to use them.[44] In Italy at around the same time, Pisanello used them if they did not clash with one of the enormous hats he liked to paint. Generally they lasted longer in Italy, although often reduced to a thin gold band depicting the outer edge of the nimbus, usual for example in Giovanni Bellini. Christ began to be shown with a plain halo.

In the

By the 19th century haloes had become unusual in Western mainstream art, although retained in iconic and popular images, and sometimes as a medievalising effect. When

Origins and usage of the different terms

The distinction between the alternative terms used in English for various types of halo is rather unclear. The oldest term in English is "glory", the only one available in the Middle Ages, but now largely obsolete. It came from the French gloire which has much the same range of meanings as "glory". "Gloriole" does not appear in this sense until 1844, being a modern invention, as a diminutive, in French also. "Halo" is first found in English in this sense in 1646 (nearly a century after the optical or astronomical sense). Both "halos" and "haloes" may be used as plural forms, and halo may be used as a verb.[47] Halo comes originally from the Greek for "threshing-floor" – a circular, slightly sloping area kept very clean, around which slaves or oxen walked to thresh the grain. In Greek, this came to mean a divine, bright disk.

Nimbus means "a cloud" in Latin, and is found as "a divine cloud" in 1616, whereas as "a bright or golden disk surrounding the head" it does not appear until 1727. The plural nimbi is correct but "rare"; "nimbuses" is not in the OED but sometimes used. Nimb is an obsolete form of the noun, but not a verb, except that the obsolete "nimbated", like the commoner "nimbate", means "furnished with a nimbus". It is sometimes preferred by art-historians, as sounding more technical than halo.[48]

Aureole, from the Latin for "golden", has been used in English as a term for a gold crown, especially that traditionally considered the reward of martyrs, since the Middle Ages (OED 1220). However, the first use recorded as a term for a halo is in 1848, very shortly after which matters were greatly complicated by the publication in 1851 of the English translation of Adolphe Napoléon Didron's important Christian Iconography: Or, The History of Christian Art in the Middle Ages. This, by what the OED calls a "strange blunder", derived the word from the Latin aura as a diminutive, and also defined it as meaning a halo or glory covering the whole body, whilst saying that "nimbus" referred only to a halo around the head. This, according to the OED, reversed the historical usage of both words, but whilst Didron's diktat was "not accepted in France", the OED noted it had already been picked up by several English dictionaries, and influenced usage in English, which still seems to be the case, as the word "nimbus" is mostly found describing whole-body haloes, and seems to have also influenced "gloriole" in the same direction.[49]

The only English term that unequivocally means a full-body halo, and cannot be used for a circular disk around the head is "mandorla", first occurring in 1883. However, this term, which is the Italian word for "almond", is usually reserved for the vesica piscis shape, at least in describing Christian art. In discussing Asian art, it is used more widely.[50] Otherwise, there could be said to be an excess of words that could refer to either a head-disk or a full-body halo, and no word that clearly denotes a full-body halo that is not vesica piscis shaped. "Halo" by itself, according to recent dictionaries,[51] means only a circle around the head, although Rhie and Thurman use the word also for circular full-body aureoles.[52]

Spiritual significance in Christianity

The early Church Fathers expended much rhetorical energy on conceptions of God as a source of light; among other things this was because "in the controversies in the 4th century over the consubstantiality of the Father and the Son, the relation of the ray to the source was the most cogent example of emanation and of distinct forms with a common substance" – key concepts in the theological thought of the time.[53]

A more

In the theology of the Eastern Orthodox Church, an icon is a "window into heaven" through which Christ and the Saints in heaven can be seen and communicated with. The gold ground of the icon indicates that what is depicted is in heaven. The halo is a symbol of the Uncreated Light (Greek: Ἄκτιστον Φῶς) or grace of God shining forth through the icon. Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite in his Celestial Hierarchies speaks of the angels and saints being illuminated by the grace of God, and in turn illumining others.

Gallery – Christian art

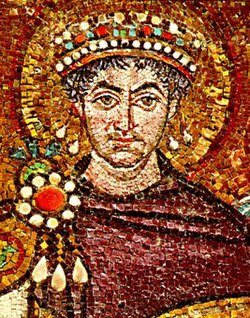

-

The EmperorJustinian (and the Empress Theodora) are haloed in mosaics at the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna, 548. See here for earlier and herefor later examples.

-

Gospels of Tsar Ivan Alexander of Bulgaria, 1355–56; the whole royal family have haloes.

-

Giotto Scrovegni Chapel, 1305, with flat perspectival haloes; the view from behind causes difficulties, and John'shalo has to be reduced in size.

-

Netherlandish, before 1430. A religious scene where objects in a realistic domestic setting contain symbolism. A wicker firescreen serves as a halo.

-

Fra Angelico 1450, Mary's halo is in perspective, Joseph's is not. Jesus still has a cruciform halo.

-

The Lutheran Hans Leonhard Schäufelein shows only Christ with a halo in this Last Supper of 1515.

-

Intwelve apostles have haloes: only Judas Iscariotdoes not.

-

Salvator Mundi, 1570, by Titian. From the late Renaissance a more "naturalistic" form of halo was often preferred.

-

William Blake uses the hats of the two girls to suggest haloes in the frontispiece to Mary Wollstonecraft's Original Stories from Real Life, 1791.

-

Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld was a member of the Nazarene movement that looked back to medieval art. However, in The Three Marys at the Tomb, 1835, only the angel has a halo.

See also

- Aura (paranormal)

- Aureola

- Crown of Immortality

- Glory (optical phenomenon)

- Glory in art

- Lesya

- Velificatio

Notes

- Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Perseus Project.

- ^ "halo – art". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ Gamal, Shaza, and Noha Moustafa Shalaby. 2023. "The Concept of the Halo: A Dialogue Between Graeco-Roman and Byzantine Egypt." International Academic Journal Faculty of Tourism and Hotel Management 9 (1):1-30.

- ^ J. Black and A. Green, Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia (Austin, 1992) p. 130.

- ^ Iliad v.4ff, xviii.203ff.

- JSTOR 3257993

- ^ L. Stephani, "Nimbus und Strahlenkranz in den Werken der Alten Kunst" in Mémoires de l'Académie des Sciences de Saint-Petersbourg, series vi, vol. vol ix, noted in Milne 1946:130.

- JSTOR 3266939.

- ^ Sali, S. A. "Daimabad : 1976–79". INDIAN CULTURE. p. 499. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- ^ a b c "Metropolitan Museum of Art: Art of South Asia" (PDF). metmuseum.org.

- ISBN 0-8109-2526-5

- ^ Rhie and Thurman, pp 77, 176, 197 etc.

- ISBN 9788120808782

- ^ "BnF. Département des Manuscrits. Supplément turc 190". Bibliothèque nationale de France. Retrieved 7 September 2023.

- ^ No doubt, as later, the same motif appeared in paintings, but none survive from this early. L Sickman & A Soper, "The Art and Architecture of China", Pelican History of Art, 3rd ed 1971, pp. 86–7, Penguin (now Yale History of Art), LOC 70-125675

- ISBN 0-7141-1447-2

- ^ Rhie and Thurman, p. 161

- ^ See Didron

- ^ Crill & Jariwala, 29 and note

- ^ Such as the Qianlong Emperor the Qianlong Emperor in Buddhist Dress, and his father.

- ^ The ring of fire is ascribed other meanings in many accounts of the iconography of the Nataraja, but many other types of statue have similar aureoles, and their origin as such is clear.

- JSTOR 868232.

- ^ Illustrated.

- ^ "Illustration". Archived from the original on 8 July 2008.

- ^ Initially only dead and therefore deified Emperors were haloed, later the living Catholic Encyclopedia

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Nimbus". www.newadvent.org.

- ^ According to the 1967 New Catholic Encyclopedia, a standard library reference, in an article on Constantine the Great: "Besides, the Sol Invictus had been adopted by the Christians in a Christian sense, as demonstrated in the Christ as Apollo-Helios in a mausoleum (c. 250) discovered beneath St. Peter's in the Vatican."

- ISBN 0-85331-270-2

- ^ "Early Christian Symbols" (PDF). Catholic Biblical Association of Canada. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 December 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2011.

- ISBN 0-85331-270-2

- ^ Nationalgallery.org.uk Archived 23 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Late 15th century reliefs by Jacopo della Quercia on the portal of San Petronio, Bologna are an early example of the triangular halo. According to Didron, Adolphe Napoléon: Christian Iconography: Or, The History of Christian Art in the Middle Ages, London, 1851, Vol 2, p30, this is "extremely rare in France, but common enough in Italy and Greece

- ^ Didron, Vol 2, pp. 68–71

- National Gallery, London, where only the beatified saints at the edges have radiating linear haloes.

- ^ only in Italy, according to Didron (but see below), Vol 2 p. 79.

- ISBN 0-300-06493-4, p. 170

- Pope Hadrian I in a mural formerly in Santa Prassede, Rome, donor figures in the church at Saint Catherine's Monastery and two more Roman examples – items 3 and 5 Archived 30 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine, one of Paschal's mother, the rather mysterious Episcopa Theodora. see also: Fisher, Sally. The Square Halo and Other Mysteries of Western Art: Images and the Stories that Inspired Them. Edited by Harriet Whelchel, Harry N Abrams, Inc., 1995

- ^ Becklectic, made by photographer. "Joshua. Fresco from the Dura Europos synagogue (Jewish Art, ed. Cecil Roth, Tel Aviv: Massadah Press, 1961, cols. 203–204: "Joshua")" – via Wikimedia Commons.

- ISBN 0719527155.

- ISBN 0-7195-3971-4

- ^ Didron, Vol 2, pp. 107–126

- ISBN 0-415-20454-2

- ISBN 978-0-7141-0525-3

- ^ Haloes were also often added by later dealers and restorers to such works, and indeed sometimes used to convert portraits into "saints". Intentional Alterations of Early Netherlandish Painting, Metropolitan Museum

- ^ If not their identity. The painting has been partly repainted, and the current appearance may not be the original one. Vienna Perugino

- ^ Tate. "'Saint Stephen', Sir John Everett Millais, Bt, 1895 – Tate". tate.org.uk.

- OEDoriginal edition for "glory", "gloriole" and "halo".

- OEDoriginal edition for "nimbus" etc.

- OEDoriginal edition for "aureole".

- ^ For example by Sickman and Soper, op. cit.

- ^ Concise Oxford Dictionary, 1995, and Collins English Dictionary.

- ^ op & pages cit. The Catholic Encyclopedia of 1911 (link above) has a further set of meanings for these terms, including glory.

- ISBN 0-7011-2514-4

References

- Aster, Shawn Zelig, The Unbeatable Light: Melammu and Its Biblical Parallels, Alter Orient und Altes Testament vol. 384 (Münster), 2012, ISBN 978-3-86835-051-7

- Crill, Rosemary, and Jariwala, Kapil. The Indian Portrait, 1560–1860, ISBN 978-1-85514-409-5

- Didron, Adolphe Napoléon, Christian Iconography: Or, The History of Christian Art in the Middle Ages, Translated by Ellen J. Millington, H. G. Bohn, (Original from Harvard University, Digitized for Google Books) – Volume I, Part I (pp. 25–165) is concerned with the halo in its different forms, though the book is not up to date.

- Dodwell, C. R., The Pictorial arts of the West, 800–1200, 1993, Yale UP, ISBN 0-300-06493-4

- Rhie, Marylin and Thurman, Robert (eds.): Wisdom And Compassion: The Sacred Art of Tibet, 1991, ISBN 0-8109-2526-5

- ISBN 0-85331-270-2

Further reading

- Ainsworth, Maryan W., "Intentional Alterations of Early Netherlandish Paintings", Metropolitan Museum Journal, Vol. 40, Essays in Memory of John M. Brealey (2005), pp. 51–65, 10, University of Chicago Press on behalf of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, JSTOR 20320643– on the later addition and removal of halos

![Chola Nataraja with an aureole of flames (11th century)[22]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/81/Shiva_Nataraja_Mus%C3%A9e_Guimet_25971.jpg/250px-Shiva_Nataraja_Mus%C3%A9e_Guimet_25971.jpg)