Hemoprotein

A hemeprotein (or haemprotein; also hemoprotein or haemoprotein), or

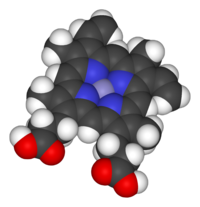

The heme consists of iron cation bound at the center of the

Hemeproteins probably evolved to incorporate the iron atom contained within the protoporphyrin IX ring of heme into proteins. As it makes hemeproteins responsive to molecules that can bind divalent iron, this strategy has been maintained throughout evolution as it plays crucial physiological functions. The serum iron pool maintains iron in soluble form, making it more accessible for cells.[3] Oxygen (O2), nitric oxide (NO), carbon monoxide (CO) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) bind to the iron atom in heme proteins. Once bound to the prosthetic heme groups, these molecules can modulate the activity/function of those hemeproteins, affording signal transduction. Therefore, when produced in biologic systems (cells), these gaseous molecules are referred to as gasotransmitters.

Because of their diverse biological functions and widespread abundance, hemeproteins are among the most studied biomolecules.[4] Data on heme protein structure and function has been aggregated into The Heme Protein Database (HPD), a secondary database to the Protein Data Bank.[5]

Roles

Hemeproteins have diverse biological functions including

Some hemeproteins—

Hemeproteins also enable

Hemoglobin and myoglobin

Hemoglobin and myoglobin are examples of hemeproteins that respectively transport and store of oxygen in mammals and in some fish.[9] Hemoglobin is a quaternary protein that occurs in the red blood cell, whereas, myoglobin is a tertiary protein found in the muscle cells of mammals. Although they might differ in location and size, their function are similar. Being hemeproteins, they both contain a heme prosthetic group.

His-F8 of the myoglobin, also known as the proximal histidine, is covalently bonded to the 5th coordination position of the iron. Oxygen interacts with the distal His by way of a hydrogen bond, not a covalent one. It binds to the 6th coordination position of the iron, His-E7 of the myoglobin binds to the oxygen that is now covalently bonded to the iron. The same is true for hemoglobin; however, being a protein with four subunits, hemoglobin contains four heme units in total, allowing four oxygen molecules in total to bind to the protein.

Myoglobin and hemoglobin are globular proteins that serve to bind and deliver oxygen using a prosthetic group. These globins dramatically improve the concentration of molecular oxygen that can be carried in the biological fluids of vertebrates and some invertebrates.

Differences occur in ligand binding and allosteric regulation.

Myoglobin

Myoglobin is found in vertebrate muscle cells and is a water-soluble globular protein.[10] Muscle cells, when put into action, can quickly require a large amount of oxygen for respiration due to their energy requirements. Therefore, muscle cells use myoglobin to accelerate oxygen diffusion and act as localized oxygen reserves for times of intense respiration. Myoglobin also stores the required amount of oxygen and makes it available for the muscle cell mitochondria.

Hemoglobin

In vertebrates, hemoglobin is found in the cytosol of red blood cells. Hemoglobin is sometimes referred to as the oxygen transport protein, in order to contrast it with myoglobin, which is stationary.

In vertebrates, oxygen is taken into the body by the tissues of the lungs, and passed to the red blood cells in the bloodstream where it's used in aerobic metabolic pathways.[10] Oxygen is then distributed to all of the tissues in the body and offloaded from the red blood cells to respiring cells. The hemoglobin then picks up carbon dioxide to be returned to the lungs. Thus, hemoglobin binds and off-loads both oxygen and carbon dioxide at the appropriate tissues, serving to deliver the oxygen needed for cellular metabolism and removing the resulting waste product, CO2.

Neuroglobin

Found in neurons, neuroglobin is responsible for driving nitric oxide to promote neuron cell survival[11] Neuroglobin is believed to increase the oxygen supply for neurons, sustaining ATP production, but they also function as storage proteins.[12]

Peroxidases and catalases

Almost all human peroxidases are hemoproteins, except glutathione peroxidase. They use hydrogen peroxide as a substrate. Metalloenzymes catalyze reactions using peroxide as an oxidant.[13] Catalases are hemoproteins responsible for the catalysis of converting hydrogen peroxide into water and oxygen.[14] They are made up of 4 subunits, each subunit having a Fe3+ heme group. They have an average molecular weight of ~240,000 g/mol.

Haloperoxidases involved in the innate immune system also contain a heme prosthetic group.

Electron transport chain and other redox catalysts

Sulfite oxidase, a molybdenum-dependent cytochrome, oxidizes sulfite to sulfate.

Nitric oxide synthase

Designed heme proteins

Due to the diverse functions of the heme molecule: as an electron transporter, an oxygen carrier, and as an enzyme cofactor, heme binding proteins have consistently attracted the attention of protein designers. Initial design attempts focused on α-helical heme binding proteins, in part, due to the relative simplicity of designing self-assembling helical bundles. Heme binding sites were designed inside the inter-helical hydrophobic grooves. Examples of such designs include:

- Helichrome[16][17]

- Globin-1[18]

- Cy-AA-EK[19]

- Peptides IIa/IId[20]

- α2[21]

- Transmembrane helical designs[22][23][24]

Later design attempts focused on creating functional heme binding helical bundles, such as:

- Oxidoreductases[25][26]

- Peroxidases[27][28]

- Electron transport proteins[29]

- Oxygen transport proteins[30]

- Photosensitive proteins[25]

Design techniques have matured to such an extent that it is now possible to generate entire libraries of heme binding helical proteins.[31]

Recent design attempts have focused on creating all-beta heme binding proteins, whose novel topology is very rare in nature. Such designs include:

Some methodologies attempt to incorporate cofactors into the hemoproteins who typically endure harsh conditions. In order to incorporate a synthetic cofactor, what must first occur is the denaturing of the holoprotein to remove the heme. The apoprotein is then rebuilt with the cofactor.[35]

References

- ^ "Heme Prosthetic Group Definition". earth.callutheran.edu. Retrieved 2023-04-27.

- ^ ISBN 1-57259-153-6.

- S2CID 2998785.

- PMID 17933771.

- ^ Gibney BR. "Heme Protein Database". Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn College.

- ^ "hemoproteins - Humpath.com - Human pathology". www.humpath.com. Retrieved 2023-04-27.

- ISBN 0-935702-73-3.

- PMID 29546752.

- PMID 34356305.

- ^ a b "Hemoglobin and Myoglobin | Integrative Medical Biochemistry Examination and Board Review | AccessPharmacy | McGraw Hill Medical". accesspharmacy.mhmedical.com. Retrieved 2023-04-27.

- S2CID 8563830.

- PMID 15143204.

- PMID 23849856, retrieved 2023-04-27

- PMID 21502693.

- ^ PMID 29695501.

- ISSN 0002-7863.

- S2CID 35536899.

- PMID 10360940.

- PMID 14595023.

- S2CID 4360174.

- ISSN 0002-7863.

- PMID 16156646.

- S2CID 20982919.

- PMID 20945900.

- ^ PMID 24121554.

- PMID 15056758.

- PMID 23150230.

- S2CID 41233353.

- PMID 24634717.

- PMID 19295603.

- PMID 14499895.

- PMID 23640811.

- PMID 28440962.

- PMID 28660027.

- PMID 34890183.

External links

- Heme Protein Database

- Hemeproteins at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)