Human uses of reptiles

Human uses of reptiles have for centuries included both symbolic and practical interactions.

Symbolic uses of

Practical uses of reptiles include the manufacture of snake antivenom and the farming of crocodiles, principally for leather but also for meat. Reptiles still pose a threat to human populations, as snakes kill some tens of thousands each year, while crocodiles attack and kill hundreds of people per year in Southeast Asia and Africa. However, people keep some reptiles such as iguanas, turtles, and the docile corn snake as pets.

Soon after their discovery in the nineteenth century,

Context

Culture consists of the

The ethnobiologist Luis Ceriaco reviews the place of reptiles in culture, as studied by ethnoherpetology, considering their practical uses, namely food, medicine, and other materials; their contribution to "ecological equilibrium", the balance of nature; and negative or fearful attitudes to them (especially snakes), causing persecution, an additional challenge for conservation. This persecution, Ceriaco states, is related to and perhaps caused by myths and folklore about the animals.[2]

More broadly,

A more recent perspective is to view the interactions of humans and reptiles as something of "more-than-human agency", in other words the subject of a multi-species study. For example, the behaviour of crocodiles "is constructed in interaction, both between people and crocodiles, and among people";[5] markedly different results depended on "institutional arrangements and attitudes towards sharing a dam with crocodiles" in different villages in Benin, where knowledge of crocodile habits reduced attacks.[5][6]

Symbolic interactions

In mythology and religion

Reptiles both real, like crocodiles

A

Crocodiles have appeared in religions across the world.

In Hinduism,

In religious terms, the snake rivals the

The Amaru, a mythological being with serpent-like characteristics, is a common motif in Andean and South American mythology.[23]

In Christianity and Judaism, a serpent appears in Genesis 3:1 to tempt

More recently, the

As symbols

The snake or serpent has played a powerful

Three medical symbols involving snakes, still used today, are the Bowl of Hygieia symbolizing pharmacy, and the Caduceus and Rod of Asclepius, symbols of medicine.[29]

The

The

In literature

Reptiles have appeared in literature since ancient times. Pliny the Elder, for instance, describes the legendary basilisk as a snake "twelve fingers in length".[36] The animal reappears many times in Western literature, including in Isidore of Seville's medieval Etymologiae,[37] and more recently in J. K. Rowling's 1998 Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets.[38] Among the many other reptiles in children's literature, Rudyard Kipling's story "How the Elephant got his Trunk" in his 1902 book Just So Stories features a crocodile who grips and stretches the elephant's nose.[39]

Turtles and tortoises feature in books for children and adults, from

Snakes, too, have played a role in literature since ancient Rome, where Cadmus kills a gigantic serpent in

The supposed weeping of insincere

In art

Reptiles including crocodiles, lizards, snakes, and

-

Tortoise figurine, ceramic, Near East, 3rd millennium BC

-

Roman snake ring, 1st century AD

-

The adoration of the bronze snake byAgnolo Bronzino, c. 1545

-

Boy Bitten by a Lizard by Caravaggio, c. 1595

-

Hippopotamus and Crocodile Hunt by Peter Paul Rubens, c. 1616

-

Nudes with Tortoise by Gyula Tornai (1861–1928)

-

Aboriginal Australianpainting with lizards and snake, 1900–1970

-

Sandsculpted dinosaurs in Australia, 2009

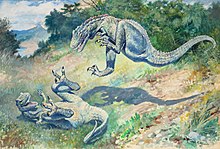

Depictions of dinosaurs

Dinosaurs have been widely depicted in culture since the English palaeontologist Richard Owen coined the name dinosaur in 1842. As soon as 1854, a group of life-sized models, the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, were on display to the public in south London.[50][51] One dinosaur appeared in literature even earlier, as Charles Dickens placed a Megalosaurus in the first chapter of his novel Bleak House in 1852.[52]

The dinosaurs featured in books, films, television programs, artwork, and other media have been used for both education and entertainment. The depictions range from the realistic, as in the television documentaries of the 1990s and first decade of the 21st century, or the fantastic, as in the monster movies of the 1950s and 1960s such as Q – The Winged Serpent.[51][53][54] These were followed by Steven Spielberg's highly successful[55][56] 1993 Jurassic Park, a film adaptation of Michael Crichton's 1990 novel, and its sequels, based on the idea of bringing a terrifying beast back from extinction by cloning from fossil DNA.[57] Critics have noticed that Jurassic Park echoes themes from Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, the aggressive Velociraptor taking the place of Frankenstein's monster.[58]

The growth in interest in dinosaurs since the

Cultural depictions have created or reinforced misconceptions about dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals, such as inaccurately and anachronistically portraying a sort of "prehistoric world" where many kinds of extinct animals (from the Permian animal Dimetrodon to mammoths and cavemen) lived together, with dinosaurs living lives of constant combat.[51][59]

Other misconceptions reinforced by cultural depictions came from a scientific consensus that has now been overturned, such as the alternate usage of dinosaur to describe something that is maladapted or obsolete, or dinosaurs as slow and unintelligent.[51][60]

Practical interactions

Food and other products

Crocodiles and alligators are

Iguana meat is popular in Mexico, a traditional food for thousands of years. Their eggs taken from pregnant females are a special delicacy.

Sea turtles, fresh water turtles, and tortoises have been eaten since prehistoric times. Because they are generally slow moving and defenseless they present an easily exploitable meat source.

Sea turtle eggs harvested from beaches have always been a part of local diets where they are laid; eggs are often traded and sold inland as a commodity. Adult sea turtles are harpooned or speared and used for meat, fat and the shell. "Tortoise shell" is usually a product of a sea turtle shell. This is used in decorative items. The oil processed from the fat is sold as turtle oil, and is used in beauty products.

Fresh water turtles are also exploited for food in the form of soup and live animals. Turtle soup as a canned luxury item was once the source of large "fisheries" on the Chesapeake Bay and the San Francisco Bay. This resulted in the near-elimination of the Diamond-back Terrapin, and the Pacific Pond Turtle in their respective estuaries.

Turtle meat is considered a delicacy in Asian cuisine, while turtle soup was once highly prized in English cuisine also.[64][65] Turtle

Land tortoises are eaten for their meat, and have their shells used in various applications as vessels, rattles, fetishes, and art objects.

Crocodile meat is occasionally eaten as an "exotic" delicacy in the western world.[67] Alligator meat is farmed for human consumption in the United States.[68][69]

In medicine

Lizards such as the

The

Reptiles including crocodilians, snakes, turtles, and lizards are used in

As threats

Deaths from snakebites are uncommon in many parts of the world, but are still counted in tens of thousands per year in India.[77] Snakebite can be treated with antivenom made from the venom of the snake. To produce antivenom, a mixture of the venoms of different species of snake is injected into the body of a horse in ever-increasing dosages until the horse is immunized. Blood is then extracted; the serum is separated, purified and freeze-dried.[78]

Large crocodiles, especially the

For entertainment

In India, snake charming is a traditional roadside show. The snake charmer carries a basket that contains a snake to which he plays tunes from his flute, to which the snake appears to dance.[80] Snakes respond to the movement of the flute, not the actual noise.[80][81]

In the Western world, a variety of reptiles including iguanas, turtles, and some snakes (especially docile species such as the

Persecution and conservation

Cultural attitudes to reptiles include a widespread fear, sometimes extending to

Several non-profit organizations around the world focus on reptile conservation, including the International Reptile Conservation Foundation,[90] and the Amphibian and Reptile Conservation Trust.[91] A peer-reviewed journal, Amphibian and Reptile Conservation, publishes research on the topic.[92]

References

- OCLC 652430995.

- ^ PMID 22316318.

- ^ OCLC 1007290568.

- ^ .

- ^ JSTOR 639326.

- S2CID 154378979.

- ^ ISBN 978-88-6244-115-5.

- ^ ISBN 1-56459-898-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-61640-924-1.

- ^ Tylor, Edward Burnett (1870). Researches Into the Early History of Mankind and the Development of Civilization. John Murray. pp. 340–343.

- Bibcode:2006MAA.....6..223R.

- ^ Persson, P.O. (1960). "Lower Cretaceous Plesiosaurians (Reptilia) from Australia". Lunds Universitets Arsskrift. 56 (12): 1–23.

- ^ ISBN 0-7537-0381-5. Archived from the originalon 9 February 2009.

- ^ Rodrigues, Hillary. "Vedic Deities | Varuna". Mahavidya. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ a b Bhattacharji, Sukumari (1970). The Indian Theogony: A Comparative Study of Indian Mythology from the Vedas to the Puranas. CUP Archive. p. 39. GGKEY:0GBP50CQXWN.

- ^ "Holy Rivers, Lakes, and Oceans". Heart of Hinduism. ISKCON Educational Services. 2004. Archived from the original on 14 October 2014.

Most rivers are considered female and are personified as goddesses. Ganga, who features in the Mahabharata, is usually shown riding on a crocodile (see right).

- ^ Kumar, Nitin (August 2003). "Ganga The River Goddess – Tales in Art and Mythology".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Hindu gods and their holy mounts". Sri. Venkateswara Zoological Park. Archived from the original on 23 June 2014.

The river goddesses, Ganga and Yamuna, were appropriately mounted on a tortoise and a crocodile respectively.

- ^ "The Crocodile is God in Goa" (PDF). Crocodile Specialist Group Newsletter. 14 (1): 8. January–March 1995.

- .

- ISBN 978-81-7182-076-4.

- ISBN 978-0-500-27928-1.

- ISBN 1-57607-354-8.

- ^ "Now the serpent was more subtil than any beast of the field which the Lord God had made. And he said unto the woman, Yea, hath God said, Ye shall not eat of every tree of the garden?" King James Version, Genesis 3:1

- ^ Owen, James (13 March 2008). "Snakeless in Ireland: Blame Ice Age, Not St. Patrick". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 14 March 2008. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ St. George and the Dragon: Introduction in: E. Gordon Whatley, Anne B. Thompson, Robert K. Upchurch (eds.), Saints' Lives in Middle English Collections (2004).

- JSTOR 541011.

- ^ Foster, Thomas Flournoy (1830). Speech on the Bill to Provide for the Removal of the Indians, West of the Mississippi: Delivered in the House of Representatives of the United States, May 17, 1830. D. Green. p. 11.

- S2CID 19125435.

- ISBN 0-500-72001-0.

- ISBN 978-0-500-01802-6.

- S2CID 130886604.

- ISBN 0-8018-8611-2.

- ISBN 0-486-43338-2.

- ISBN 0-313-31505-1.

- ^ viii. 33 Pliny the Elder (1855). The Natural History. Translated by Bostock, John; Riley, Henry Thomas.

- ISBN 978-1-139-45616-6.

- The Royal Society. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ Du Toit, Adele (30 December 2014). "How the elephant got his trunk — classic story plays out in Kruger". News24. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ^ Ashliman, D. L. (2011). "The Tortoise and the Hare and other races between unequal contestants". University of Pittsburgh. Retrieved 7 October 2018.

- ^ Miller, Matt (13 September 2017). "There Are Two Important Clues in It That Only Real Stephen King Fans Will Notice". Esquire. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ a b c Mullan, John (8 July 2011). "Ten of the best | Snakes in literature". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ISBN 978-2-251-32227-8.

- ISBN 978-1-4092-3184-4.

- ^ Britton, Adam (n.d.). Do crocodiles cry 'crocodile tears'? Crocodilian Biology Database. Retrieved 13 March 2006 from the Crocodile Specialist Group, Crocodile Species List, FAQ.

- ^ Kjellgren, Eric. "Crocodiles". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ Lesser, Casey (14 September 2017). "The Renaissance Artist Who Cast Live Snakes, Frogs, and Lizards to Make His Ceramics". Artsy.net. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- The Tatler. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ISBN 0-451-79961-5.

- ^ Torrens, Hugh. "Politics and Paleontology". The Complete Dinosaur, 175–190.

- ^ ISBN 0-253-33349-0.

- ^ "London. Michaelmas term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln's Inn Hall. Implacable November weather. As much mud in the streets, as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, forty feet long or so, waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborne Hill." From page 1 of Dickens, Charles J.H. (1852). Bleak House, Chapter I: In Chancery. London: Bradbury & Evans.

- ^ ISBN 0-312-26226-4.

- ISBN 0-8109-0922-7.

- ^ Jurassic Park – Movie Reviews, Trailers, Pictures – Rotten Tomatoes. Rottentomatoes.com. Retrieved on 4 September 2012.

- ^ "Jurassic Park (1993) – Box Office Mojo". www.boxofficemojo.com.

- ^ "Jurassic Park". MichaelCrichton.com. Retrieved 1 January 2009.

- ISBN 978-0-7864-2672-0.

- ISBN 0-07-303642-0.

- ^ "dinosaur". Dictionary.com. Lexico. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ^ Lyman, Rick (30 November 1998). "Anahuac Journal; Alligator Farmer Feeds Demand for All the Parts". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- ^ Country Folk Medicine: Tales of Skunk Oil, Sassafras Tea, and Other Old-time Remedies (2004) Elisabeth Janos. p. 56.

- S2CID 248733239.

- ^ Barzyk, J. E. (November 1999). "Turtles in Crisis: The Asian Food Markets". Tortoise Trust. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ Old fashioned turtle soup recipe. 1881. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - S2CID 86821249.

- ^ Armstrong, Hilary (8 April 2009). "Best exotic restaurants in London". Evening Standard. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ISBN 978-1-56676-889-4.

- ISBN 978-1-56305-346-7.

- ^ Irvine, F. R. (1954). "Snakes as food for man". British Journal of Herpetology. 1 (10): 183–189.

- ^ Connor, Neil (4 October 2013). "Here's What Men in Asia Eat To Boost Their Libidos". Business Insider. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ^ "蛇酒的泡制与药用(The production and medicinal qualities of snake wine)". 9 April 2007. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ^ Shepherd, Katie (19 March 2020). "John Cornyn criticized Chinese for eating snakes. He forgot about the rattlesnake roundups back in Texas". The Washington Post. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- ^ Casey, Constance (26 April 2013). "Don't Call It a Monster". Slate.

- ^ "Alzheimer's research seeks out lizards". BBC. 5 April 2002.

- PMID 23593597.

- ^ Sinha, Kounteya (25 July 2006). "No more the land of snake charmers..." The Times of India.

- PMID 8939322.

- ^ "Crocodilian Attacks". IUCN Crocodile Specialist Group. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ^ a b Bagla, Pallava (23 April 2002). "India's Snake Charmers Fade, Blaming Eco-Laws, TV". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 21 May 2006. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ^ "Snake charmer's bluff" International Wildlife Encyclopedia, 3rd edition, page 482

- ^ S2CID 3425878.

- ^ ISBN 1-56098-648-4.

- ISBN 978-1-4020-6028-1.

- ISBN 978-0-345-34629-2.

- S2CID 243839768.

- ^ "Bushmeat". Center for International Forestry Research. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- .

- JSTOR 1565247.

- ^ "Welcome to the IRCF". IRCF. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ^ "Amphibian and Reptile Conservation". ARC Trust. Retrieved 6 October 2018.

- ^ "Amphibian & Reptile Conservation". Amphibian & Reptile Conservation. Retrieved 6 October 2018.