Laquintasaura

| Laquintasaura | |

|---|---|

| |

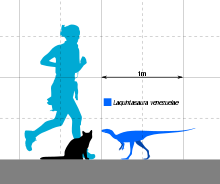

| Reconstruction of Laquintasaura venezuelae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Genus: | †Laquintasaura Barrett et al., 2014

|

| Species: | †L. venezuelae

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Laquintasaura venezuelae Barrett et al., 2014 | |

Laquintasaura is a genus of

Discovery and naming

The bonebed would produce material eventually named as Laquintasaura was originally discovered in the 1980s, by a team of French palaeontologists. The bonebed is found near a road between the towns of La Grita and Seboruco, in the Táchira state of Venezuela, in rocks pertaining to the Early Jurassic La Quinta Formation; it is directly opposite to the type section of the formation, separated by possible geologic faults. These initial French discoveries - two teeth and a quadrate would be brought to Paris and described by D.E. Russel and colleagues in a 1992 study; based on similar cranial anatomy, they were referred to the genus Lesothosaurus, an early ornithischian from the Early Jurassic of Lesotho and South Africa. Unaware of the French team's discoveries, Marcelo R. Sánchez-Villagra and colleagues would make their own expeditions into the La Quinta Formation; initially finding no vertebrate fossils in 1989, they'd later rediscover the bonebed in the first of three expeditions in 1992 and 1993; dinosaur expert James Clark was the one to first notice the easy to miss locality. A few plaster jackets worth of fossils were recovered and transported by Sánchez-Villagra to Buenos Aires in Argentina, where he and the team of Dr. Guillermo Rougier spent three months partially preparing the fossils. After this they were returned to Venezuela, being brought to Universidad Simón Bolívar where Sánchez-Villagra had written his thesis. Several years later in the late 1990s, Sánchez-Villagra would become aware of the French specimens and co-ordinate their return to Venezuela as well, deposited in the collections of the Museu de Biología de la Universidad de Zulia (MBLUZ).[1]

Sánchez-Villagra become aware he was no longer permitted to study the fossils that had been deposited at the Universidad Simón Bolívar soon after they have been transferred, and resolved to conduct new expeditions to gather additional material from the bonebed; the Universidad Simón Bolívar material has gone unstudied since. Shortly before hearing this news an attempted expedition had failed due to a truck failure. A successful trip was organized in December 1993, with a new team from Caracas, which produced abundant new material. This was deposited in the MBLUZ, like the original French material. Early preparation of these blocks was reported on at the 1994 conference of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. Sánchez-Villagra and Fernando Novas, who had met during the preparation in Buenos Aires, obtained a grant from the Jurassic Foundation to study the 1993 material. The project would eventually become based in the Natural History Museum in London, England and would bring in Paul Barrett. He, Novas, Sánchez-Villagra, and colleagues would finally publish on the material in a 2008 paper in the scientific journal PalZ, identifying a likely new genus of ornithischian among many other indeterminate animals but not naming it until further material was known.[1]

That further material would become recognized and published on in a 2014 paper in the journal

Hundreds of individual fossil elements are known for Laquintasaura, representing a minimum of four individuals and potentially many more. The majority of known remains are thought to represent subadult individuals, but one small

Description

Like other early members of Ornithischia, it is assumed that Laquintasaura was a lithe

The most distinctive part of the anatomy is Laquintasaura is found in its

The

The

Classification

The specifics of the

Palaeoecology

Laquintasaura hails from the La Quinta Formation of northern South America, in what is now Colombia and Venezuela, and was found in the Venezuelan part of the formation.

The ecosystem that Laquintasaura lived in is thought to represent an

The exact nature of the taphonomy of the Laquintasaura bonebed remains incompletely studied. The remains are thought to have undergone some degree of low-energy transport, but the lack of any damage to the bones, or signs of things like plant root damage or insect boring holes, indicating the remains were not exposed for a long time prior to being buried.[3] The bonebed is entirely devoid of microfossils, invertebrates, or plant remains, and is palynologically barren; the only other animal found at the site is the scant remains of Tachiraptor.[2][3] All of this indicates the four or more individuals at the site likely died together and maybe have lived together in life, indicative of social behaviour. Herding is known in ornithischians of the Late Jurassic and Cretaceous, but its presence in Laquintasaura would be the first recognized in such an early member of the group (though more recent research has also indicated presence in the genus Lesothosaurus[11]).[3]

References

- ^ .

- ^ PMID 26064540.

- ^ PMID 25100698.

- PMC 8929930.

- ^ .

- .

- S2CID 90051025.

- PMID 33194351.

- ^ ISSN 0024-4082.

- S2CID 55613546.

- ^ .

- ^ .

- PMID 34966571.

- ^ .

- .

- ^ a b "New dinosaur discovered in Venezuela". Royal Society. 6 August 2014. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "Tachiraptor admirabilis: New Carnivorous Dinosaur Unearthed in Venezuela". Sci-News. 10 October 2014. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- The Huffington Post. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- PMC 5335715.

- .