Louis Sullivan

Louis Henry Sullivan | |

|---|---|

c. 1895 | |

| Born | September 3, 1856 Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died | April 14, 1924 (aged 67) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Occupation | Architect |

Louis Henry Sullivan (September 3, 1856 – April 14, 1924)

Early life and career

Sullivan was born to a Swiss-born mother, née Andrienne List (who had emigrated to Boston from Geneva with her parents and two siblings, Jenny, b. 1836, and Jules, b. 1841) and an Irish-born father, Patrick Sullivan. Both had immigrated to the United States in the late 1840s.[7] He learned that he could both graduate from high school a year early and bypass the first two years at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology by passing a series of examinations. Entering MIT at the age of sixteen, Sullivan studied architecture there briefly. After one year of study, he moved to Philadelphia and took a job with architect Frank Furness.

The

Sullivan and the steel high-rise

Prior to the late nineteenth century, the weight of a multi-story building had to be supported principally by the strength of its walls. The taller the building, the more strain this placed on the lower sections of the building; since there were clear engineering limits to the weight such "load-bearing" walls could sustain, tall designs meant massively thick walls on the ground floors, and definite limits on the building's height.

The development of cheap, versatile steel in the second half of the nineteenth century changed those rules. America was in the midst of rapid social and economic growth that made for great opportunities in architectural design. A much more urbanized society was forming and the society called out for new, larger buildings. The mass production of steel was the main driving force behind the ability to build skyscrapers during the mid-1880s. By assembling a framework of steel girders, architects and builders could create tall, slender buildings with a strong and relatively lightweight steel skeleton. The rest of the building elements—walls, floors, ceilings, and windows—were suspended from the skeleton, which carried the weight. This new way of constructing buildings, so-called "column-frame" construction, pushed them up rather than out. The steel weight-bearing frame allowed not just taller buildings, but permitted much larger windows, which meant more daylight reaching interior spaces. Interior walls became thinner, which created more usable (and rentable) floor space.

Chicago's Monadnock Building (not designed by Sullivan) straddles this remarkable moment of transition: the northern half of the building, finished in 1891, is of load-bearing construction, while the southern half, finished only two years later, is of column-frame construction. While experiments in this new technology were taking place in many cities, Chicago was the crucial laboratory. Industrial capital and civic pride drove a surge of new construction throughout the city's downtown in the wake of the 1871 fire.

The technical limits of weight-bearing masonry had imposed formal as well as structural constraints; suddenly, those constraints were gone. None of the historical precedents needed to be applied and this new freedom resulted in a technical and stylistic crisis of sorts. Sullivan addressed it by embracing the changes that came with the steel frame, creating a grammar of form for the high rise (base, shaft, and cornice), simplifying the appearance of the building by breaking away from historical styles, using his own intricate floral designs, in vertical bands, to draw the eye upward and to emphasize the vertical form of the building, and relating the shape of the building to its specific purpose. All this was revolutionary, appealingly honest, and commercially successful.

In 1896, Louis Sullivan wrote:

It is the pervading law of all things organic and inorganic, of all things physical and metaphysical, of all things human, and all things super-human, of all true manifestations of the head, of the heart, of the soul, that the life is recognizable in its expression, that form ever follows function. This is the law. (italics in original)[9]

"Form follows function" would become one of the prevailing tenets of modern architects.

Sullivan attributed the concept to

Such ornaments, often executed by the talented younger draftsmen in Sullivan's employ, eventually would become Sullivan's trademark; to students of architecture, they are instantly recognizable as his signature.

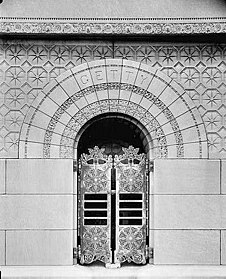

Another signature element of Sullivan's work is the massive, semi-circular arch. Sullivan employed such arches throughout his career—in shaping entrances, in framing windows, or as interior design.

All of these elements are found in Sullivan's widely admired

Because Sullivan's remarkable accomplishments in design and construction occurred at such a critical time in architectural history, he often has been described as the "father" of the American skyscraper. But many architects had been building skyscrapers before or as contemporaries of Sullivan; they were designed as an expression of new technology. Chicago was replete with extraordinary designers and builders in the late years of the nineteenth century, including Sullivan's partner,

Later career and decline

In 1890, Sullivan was one of the ten U.S. architects, five from the east and five from the west, chosen to build a major structure for the "White City", the World's Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago in 1893. Sullivan's massive Transportation Building and huge arched "Golden Door" stood out as the only building not of the current Beaux-Arts style, and with the only multicolored facade in the entire White City. Sullivan and fair director Daniel Burnham were vocal about their displeasure with each other. Sullivan later claimed (1922) that the fair set the course of American architecture back "for half a century from its date, if not longer."[11] His was the only building to receive extensive recognition outside America, receiving three medals from the French-based Union Centrale des Arts Decoratifs the following year.

Like all American architects, Adler and Sullivan suffered a precipitous decline in their practice with the onset of the Panic of 1893. According to Charles Bebb, who was working in the office at that time, Adler borrowed money to try to keep employees on the payroll.[12] By 1894, however, in the face of continuing financial distress with no relief in sight, Adler and Sullivan dissolved their partnership. The Guaranty Building was considered the last major project of the firm.

By both temperament and connections, Adler had been the one who brought in new business to the partnership, and following the rupture Sullivan received few large commissions after the Carson Pirie Scott Department Store. He went into a twenty-year-long financial and emotional decline, beset by a shortage of commissions, chronic financial problems, and alcoholism. He obtained a few commissions for small-town Midwestern banks (see below), wrote books, and in 1922 appeared as a critic of Raymond Hood's winning entry for the Tribune Tower competition.

In 1922, Sullivan was paid $100 a month to write an autobiography in installments to be published in the journal for the American Institute of Architects. Sullivan worked on the series with Journal editor Charles Harris Whitaker, who advised he "plot out the material by periods."[13] The Autobiography of an Idea began its publication in the June 1922 Journal for the American Institute of Architects[14] and upon its conclusion was published as a book.

He died in a Chicago hotel room on April 14, 1924. He left a wife, Mary Azona Hattabaugh, from whom he was separated. A modest headstone marks his final resting spot in Graceland Cemetery in Chicago's Uptown and Lake View neighborhood. Later, a monument was erected in Sullivan's honor, a few feet from his headstone.

Legacy

Sullivan's legacy is contradictory. Some consider him the first modernist.

After his death Sullivan was referred to as a bold architect: "Boldly he challenged the whole theory of copying and imitating, and the catchword of "precedent," declaring that architecture was naturally a living and creative art."[16]

Original drawings and other archival materials from Sullivan are held by the

Preservation

During the postwar era of urban renewal, Sullivan's works fell into disfavor, and many were demolished. In the 1970s, growing public concern for these buildings finally resulted in many being saved. The most vocal voice was Richard Nickel, who organized protests against the demolition of architecturally significant buildings.[17] Nickel and others sometimes rescued decorative elements from condemned buildings, sneaking in during demolition. Nickel died inside Sullivan's Stock Exchange building while trying to retrieve some elements, when a floor above him collapsed. Nickel had compiled extensive research on Adler and Sullivan and their many architectural commissions, which he intended to publish in book form.

After Nickel's death, in 1972 the Richard Nickel Committee was formed, to arrange for completion of his book, which was published in 2010. The book features all 256 commissions of Adler and Sullivan. The extensive archive of photographs and research that underpinned the book was donated to the Ryerson and Burnham Libraries at The Art Institute of Chicago. More than 1,300 photographs may be viewed on their website and more than 15,000 photographs are part of the collection at The Art Institute of Chicago. As finally published, the book, The Complete Architecture of Adler & Sullivan, was authored by Richard Nickel, Aaron Siskind, John Vinci, and Ward Miller.

Another champion of Sullivan's legacy was the architect Crombie Taylor (1907–1991), of Crombie Taylor Associates. After working in Chicago, where he had headed the famous "Institute of Design", later known as the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT), in the 1950s and early 1960s, he had moved to Southern California. He led the effort to save the Van Allen Building in Clinton, Iowa from demolition.[18] Taylor, acting as an aesthetic consultant, had worked on the renovation of the Auditorium Building (now Roosevelt University) in Chicago.[19]

When he read an article about the planned demolition in Clinton, he uprooted his family from their home in southern California and moved them to Iowa. With the vision of a destination neighborhood comparable to Oak Park, Illinois, he set about creating a nonprofit to save the building, and was successful in doing so. Another advocate both of Sullivan buildings and of Wright structures was Jack Randall, who led an effort to save the Wainwright Building in St. Louis, Missouri at a very critical time. He relocated his family to Buffalo, New York to save Sullivan's Guaranty Building and Frank Lloyd Wright's Darwin Martin House from possible demolition. His efforts were successful in both St. Louis and Buffalo.

A collection of architectural ornaments designed by Sullivan is on permanent display at Lovejoy Library at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville.[20] The St. Louis Art Museum also has Sullivan architectural elements displayed. The City Museum in St. Louis has a large collection of Sullivan ornamentation on display, including a cornice from the demolished Chicago Stock Exchange, 29 feet long on one side, 13 feet on another, and nine feet high.[21]

The Guaranty Building Interpretive Center in Buffalo, on the first floor of the building now owned and occupied by the law firm Hodgson Russ, LLP, opened in 2017. The exhibit space was financed by Hodgson Russ, LLP, and co-designed by Flynn Battaglia Architects and Hadley Exhibits. It features a scale model of the building by David J. Carli, Professor of Engineering at the State University of New York at Alfred. The center's exhibits were donated to Preservation Buffalo Niagara. The center, the only museum dedicated to Sullivan, is open to the public.[22]

Sullivan in Ayn Rand's The Fountainhead

That the fictional character of Henry Cameron in Ayn Rand's 1943 novel The Fountainhead was similar to the real-life Sullivan was noted, if only in passing, by at least one journalist contemporary to the book.[23]

Although Rand's journal notes contain in toto only some 50 lines directly referring to Sullivan, it is clear from her mention of Sullivan's Autobiography of an Idea (1924) in her 25th-anniversary introduction to her earlier novel We the Living (first published in 1936, and unrelated to architecture) that she was intimately familiar with his life and career.[24] The term "the Fountainhead," which appears nowhere in Rand's novel proper, is found twice (as "the fountainhead" and later as "the fountain head") in Sullivan's autobiography, both times used metaphorically.[25]

The fictional Cameron is, like Sullivan – whose physical description he matches – a great innovative skyscraper pioneer late in the nineteenth century who dies impoverished and embittered in the mid-1920s. Cameron's rapid decline is explicitly attributed to the wave of classical Greco-Roman revivalism in architecture in the wake of the

The major difference between novel and real life was in the chronology of Cameron's relation with his protégé Howard Roark, the novel's hero, who eventually goes on to redeem his vision. That Roark's uncompromising individualism and his innovative organic style in architecture were drawn from the life and work of Frank Lloyd Wright is clear from Rand's journal notes, her correspondence, and various contemporary accounts.[27][28] In the novel, however, the 23-year-old Roark, a generation younger than the real-life Wright, becomes Cameron's protégé in the early 1920s, when Sullivan was long in decline.

The young Wright, by contrast, was Sullivan's protégé for seven years, beginning in 1887, when Sullivan was at the height of his fame and power. The two architects would sever their ties in 1894 due to Sullivan's angry reaction to Wright's moonlighting in breach of his contract with Sullivan, but Wright continued to call Sullivan "lieber Meister" ("beloved Master") for the rest of his life.[29] After decades of estrangement, Wright would again become close to the now-destitute Sullivan in the early 1920s, the time when Roark first comes under the likewise impoverished Cameron's tutelage in the novel.[30] Wright, however, was now in his fifties. Nevertheless, both the young Roark and middle-aged Wright had in common at that time that they both faced a decade of struggle ahead. After the triumphs earlier in his career, Wright came increasingly to be viewed as a has-been, until he experienced a renaissance in the latter half of the 1930s with such projects as Fallingwater and the Johnson Wax Headquarters.[31]

Selected projects

Buildings 1887–1895 by Adler & Sullivan:

- Martin Ryerson Tomb, Graceland Cemetery, Chicago (1887)

- Auditorium Building, Chicago (1889)

- Carrie Eliza Getty Tomb, Graceland Cemetery, Chicago (1890)

- Wainwright Building, St. Louis (1890)

- Charlotte Dickson Wainwright Tomb, Bellefontaine Cemetery, St. Louis (1892), listed on the National Register of Historic Places (shown at right),[32][33][34] is considered a major American architectural triumph,[35] a model for ecclesiastical architecture,[36] a "masterpiece",[37] and has been called "the Taj Mahal of St. Louis." The family name appears nowhere on the tomb.[38]

- Union Trust Building , St. Louis (1893; street-level ornament heavily altered in 1924)

- Guaranty Building (formerly Prudential Building), Buffalo(1894)

Buildings 1887–1922 by Louis Sullivan: (256 total commissions and projects)

- Springer Block (later Bay State Building and Burnham Building) and Kranz Buildings, Chicago (1885–1887)

- Selz, Schwab & Company Factory, Chicago (1886–1887)

- Hebrew Manual Training School, Chicago (1889–1890)

- James H. Walker Warehouse & Company Store, Chicago (1886–1889)

- Warehouse for E. W. Blatchford, Chicago (1889)

- James Charnley House (also known as the Charnley–Persky House Museum Foundation and the National Headquarters of the Society of Architectural Historians), Chicago (1891–1892)

- Albert Sullivan Residence, Chicago (1891–1892)

- McVicker's Theater, second remodeling, Chicago (1890–1891)

- Bayard Building, (now Bayard-Condict Building), 65–69 Bleecker Street, New York City (1898). Sullivan's only building in New York, with a glazed terra cottacurtain wall expressing the steel structure behind it.

- Commercial Loft of Gage Brothers & Company, Chicago (1898–1900)

- Holy Trinity Russian Orthodox Cathedral and Rectory, Chicago (1900–1903)

- Carson Pirie Scott store, (originally known as the Schlesinger & Mayer Store, now known as "Sullivan Center") Chicago (1899–1904)

- Virginia Hall of Tusculum College, Greeneville, Tennessee (1901)[39]

- Van Allen Building, Clinton, Iowa (1914)

- St. Paul United Methodist Church, Cedar Rapids, Iowa (1910)

- Krause Music Store, Chicago (final commission 1922; front façade only)

Banks

By the end of the first decade of the twentieth century, Sullivan's star was well on the descent[according to whom?] and, for the remainder of his life, his output consisted primarily of a series of small bank and commercial buildings in the Midwest. Yet a look at these buildings clearly reveals[according to whom?] that Sullivan's muse had not abandoned him. When the director of a bank that was considering hiring him asked Sullivan why they should engage him at a cost higher than the bids received for a conventional Neo-Classic styled building from other architects, Sullivan is reported to have replied, "A thousand architects could design those buildings. Only I can design this one." He got the job. Today[when?] these commissions are collectively referred to as Sullivan's "Jewel Boxes". All still stand.

- Peoples Savings Bank, Cedar Rapids, Iowa (1912)

- Henry Adams Building, Algona, Iowa (1913)

- Merchants' National Bank, Grinnell, Iowa (1914)

- Home Building Association Company, Newark, Ohio (1914)

- Purdue State Bank, West Lafayette, Indiana (1914)

- People's Federal Savings and Loan Association, Sidney, Ohio (1918)

- Farmers and Merchants Bank, Columbus, Wisconsin (1919)

- First National Bank, Manistique, Michigan (1919–1920), a remodeling of an existing bank building [41]

Lost buildings

- Grand Opera House, Chicago, 1880 remodel and reconstruction with Dankmar Adler as lead architect and Sullivan as assistant; later remodeled and reconstructed in 1926 by Andrew Rebori; demolished May 1962[42]

- Washington Elementary School, Marengo, Illinois, Adler & Sullivan, 1883, demolished by early 1990s[43][44]

- Pueblo Opera House, Pueblo, Colorado, 1890, destroyed by fire 1922

- New Orleans Union Station, 1892, demolished 1954

- Dooly Block, Salt Lake City, Utah, 1891, demolished 1965

- Chicago Stock Exchange Building, Adler & Sullivan, 1893, demolished 1972

- The trading room from the Stock Exchange was removed intact prior to the building being demolished and subsequently, was restored in the Art Institute of Chicago in 1977; the entryway arch (seen at right) stands outside on the northeast corner of the AIC site

- Zion Temple, Chicago, 1884, demolished 1954

- Troescher Building, Chicago, 1884, demolished 1978

- Transportation Building, World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, Adler & Sullivan, 1893–94, an exposition building built to last a year

- Louis Sullivan and Charnley Cottages, Ocean Springs, Mississippi, destroyed in Hurricane Katrina; Frank Lloyd Wright also claimed credit for the design

- Schiller Building (later Garrick Theater), Chicago, Adler & Sullivan, 1891, demolished 1961[45]

- Third McVickers Theater, Chicago, Adler & Sullivan, 1883? demolished 1922

- Thirty-Ninth Street Passenger Station, Chicago, Adler & Sullivan, 1886, demolished 1934

- Standard Club, Chicago, Adler & Sullivan, 1887–88, demolished 1931

- Pilgrim Baptist Church, Chicago, Adler & Sullivan, 1891, destroyed by fire January 6, 2006

- Wirt Dexter Building, Chicago, Adler & Sullivan, 1887, destroyed by fire October 24, 2006

- George Harvey House, Chicago, Adler & Sullivan, 1888 destroyed by fire November 4, 2006

Gallery

-

Wainwright Building cornice

-

Auditorium Building

-

Chicago Stock ExchangeBuilding

-

Bayard-Condict Building

-

Carson Pirie Scott store

-

Gage Building(on right)

-

Holy Trinity Russian Orthodox Cathedral, exterior

-

Holy Trinity Russian Orthodox Cathedral, interior

-

National Farmer's Bank of Owatonna

-

Harold C. Bradley House, Wisconsin

-

Krause Music Store

-

Farmers and Merchants Union Bank, Columbus, Wisconsin

See also

- American Prize for Architecture

- Richard Bock

- Tall: The American Skyscraper and Louis Sullivan

References

Notes

- ^ The spelling of Sullivan's middle name (whether Henry or Henri) has caused confusion. According to Robert Twombly, Louis Sullivan – His Life and Work (Elizabeth Sifton Books, New York City, 1986), his birth certificate read Henry Louis Sullivan, although he was called Louis Henry. Sullivan helped propagate confusion over his middle name as well by announcing, in his book Autobiography of an Idea, which he wrote at the end of his life, at a time when professional failure and alcohol may have clouded his judgment, that he had been named Louis Henri after his grandfather Henri List (see footnote below). The latter spelling was in turn enshrined by the designers of his funerary monument (see picture in text).

- ^ Kaufman, Mervyn D. (1969). Father of Skyscrapers: A Biography of Louis Sullivan. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

- ^ Chambers Biographical Dictionary. London: Chambers Harrap, 2007. s.v. "Sullivan, Louis Henry," http://www.credoreference.com/entry/chambbd/sullivan_louis_henry (subscription required)

- ISBN 978-0-226-62071-8.

- .

- ^ "Gold Medal Award Recipients". The American Institute of Architects. Archived from the original on March 13, 2016. Retrieved March 12, 2016.

- ^ Sullivan, Louis H. Autobiography of an Idea. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, 2009 (reprint of 1924 edition), p. 31. This reference illustrates Sullivan's adoption of the "Henri" spelling of his middle name towards the end of his life.

- ^ Louis Sullivan at www.prairiestyles.com

- ^ Sullivan, Louis. "The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered", Lippincott's Monthly Magazine (March 1896)

- ^ Sullivan, Louis (1924). Autobiography of an Idea. New York City: Press of the American institute of Architects, Inc. p. 108.

- ^ Sullivan, Louis (1924). Autobiography of an Idea. New York City: Press of the American institute of Architects, Inc. p. 325.

- ^ Jeffrey Karl Ochsner and Dennis Alan Andersen, Distant Corner: Seattle Architects and the Legacy of H.H. Richardson (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2003), 287-288.

- ISBN 978-1-258-15389-2. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Sullivan, Louis (June 1922). "The Autobiography of an Idea". American Institute of Architects. 10 (6): 178. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- S2CID 144344744.

- ^ Whitaker, Charles (1934). The Story of Architecture: from Rameses to Rockefeller. New York: Halycon House. p. 242.

- ISBN 0-471-14426-6.

- ISBN 978-0-9660273-2-7.

- ISBN 0-226-76133-9.

- ^ "Sullivan Collection in Lovejoy Library". Archived from the original on October 27, 2013.

- ^ "The City Museum in Saint Louis will do anything—even risk eternal damnation—to build its Louis Sullivan collection". Chicago Reader. May 30, 2018. Retrieved September 15, 2020.

- ^ "Visitors now welcome at landmark Guaranty Building". The Buffalo News. January 26, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2017.

- ^ Life magazine; September 2, 1946; reply by editor to reader's letter, p.22

- ^ "My view of what a good autobiography should be is contained in the title that Louis H. Sullivan gave to the story of his life: The Autobiography of an Idea." Rand, Ayn (2009) [1958]. "Forward". We the Living. New American Library. pp. xiii. This is the total mention by Rand; she does not bother to tell the reader that Sullivan was an architect or anything else about him.

- ^ Sullivan, Louis H. (2009) [1924]. Autobiography of an Idea. Dover Publications. pp. 20, 213.

- ^ Rand, Ayn (1943). The Fountainhead. Bobbs-Merrill. pp. 34–35.; Sullivan, Louis H. (1924). The Autobiography of an Idea. pp. 324–327.

- ^ Rand, Ayn. The Journals of Ayn Rand Plume, 1999. Section 5

- ^ Rand, Ayn The Letters of Ayn Rand New York: Dutton, 1995. Section 3

- ^ Wright, Frank Lloyd (1949). Genius and Mobocracy. Duell Sloan & Pearce. pp. 66–67.

- ^ Wright, Frank Lloyd (1949). Genius and Mobocracy. Duell Sloan & Pearce. pp. 71–76.

- ^ Toker, Franklin. Fallingwater Rising. Alfred A. Knopf. pp. 14–15.

- ^ Architectural Plans for Wainwright tomb, The Steedman Exhibit. Archived July 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Wainwright Tomb - St. Louis, Missouri - American Guide Series on Waymarking.com". Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ^ Historic Americal Buildings Survey, MO-1637A, Wainwright Tomb.[permanent dead link]

- (April 16, 1999)

- ^ Abeln, Mark Scott. "Two by Sullivan". Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ^ Chase, Theodore. (ed.) Markers V Journal of the Association for Gravestone Studies Lapham Maryland: University Press of America, 1988, at Internet Archive

- ^ St. Louis' Historic Cemeteries Offer Final Rest for the Rich and Famous.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Tusculum College Archived December 13, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Why a Minnesota bank building ranks among the nation’s most significant architecture", PBS NewsHour, June 15, 2022.

- ^ Twombly. Robert, Louis Sullivan: His life and work, Elisabeth Sifton Books, New York, 1986 p. 458

- ISBN 978-0-7864-8865-0.

- ^ "OFFICIALS AT ODDS OVER FUTURE OF HISTORIC BUILDING". Chicago Tribune. December 28, 1988. Retrieved July 13, 2023.

- ^ "Louis Sullivan More". Stories, Structures, and Songs. April 13, 2013. Retrieved July 13, 2023.

- ^ "Home". Archived from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

Bibliography

- Columbian Gallery – A Portfolio of Photographs of the World's Fair, The Werner Company, Chicago, IL, 1894.

- Condit, Carl W., The Chicago School of Architecture, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, 1964.

- Connely, Willard, Louis Sullivan as He Lived, Horizon Press, Inc., NY, 1960.

- Engelbrecht, Lloyd C., "Adler and Sullivan's Pueblo Opera House: City Status for a New Town in the Rockies", The Art Bulletin, College Art Association of America, June 1985.

- Gebhard, David (May 1960). "Louis Sullivan and George Grant Elmslie". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 19 (2): 62–68. JSTOR 988008.

- Hoffmann, Donald (January 13, 1998). Frank Lloyd Wright, Louis Sullivan, and the skyscraper. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-40209-3. Retrieved March 27, 2011.

- Morrison, Hugh, Louis Sullivan – Prophet of Modern Architecture, W.W. Norton & Co., Inc. New York City, 1963.

- Nickel, Richard; Siskind, Aaron; Vinci, John; and Miller, Ward. The Complete Architecture of Adler & Sullivan, Richard Nickel Committee, Chicago, Illinois, 2010.

- Sullivan, Louis, The Autobiography of an Idea, Press of the American institute of Architects, Inc., New York City, 1924.

- Sullivan, Louis, Kindergarten Chats and Other Writings, Dover Publications, Inc., New York City, 1979.

- Sullivan, Louis, Louis Sullivan: The Public Papers Ed. Robert Twombly, Chicago University Press, Chicago & London, 1988

- Thomas, George E.; Cohen, Jeffrey A.; and Lewis, Michael J.; Frank Furness – The Complete Works, Princeton Architectural Press, New York City, 1991.

- Twombly, Robert, Louis Sullivan – His Life and Work, Elizabeth Sifton Books, New York City, 1986.

- Vinci, John, The Art Institute of Chicago: The Stock Exchange Trading Room, The Art Institute of Chicago, 1977.

- Weingarden, Lauren S. Louis H. Sullivan: A System of Architectural Ornament [1924]. Art Institute of Chicago and Ernst Wasmuth Verlag (Germany); distributed by Rizzoli International (U.S.), Wasmuth (Germany), Mardaga (France), 1990.

- Weingarden, Lauren S. Louis H. Sullivan: The Banks. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1987.

External links

- Book: "The Complete Architecture of Adler & Sullivan" by Richard Nickel, Aaron Siskind, John Vinci and Ward Miller

- Atlantic.com slideshow, "The Architecture of Louis Sullivan," with photographs by Richard Nickel and others

- Article on fragments of Adler and Sullivan Buildings in Chicago

- "Sullivan's Banks" documentary by Heinz Emigholz

- Louis H. Sullivan Ornaments – digital photographs of ornaments with historic photographs of the original buildings

- Louis Sullivan "The tall office building artistically considered" – Transcribed from Lippincott's Magazine (March 1896)

- Works by Louis Sullivan at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)