Mammaliaformes

| Mammaliaforms | |

|---|---|

| |

| Top: Megazostrodon rudnerae, Morganucodon watsoni (Morganucodonta); Middle: Castorocauda lutrasimilis (Docodonta), Shenshou lui (Haramiyida); | |

| |

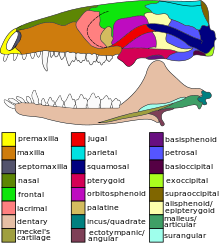

| Skull of Morganucodon | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Clade: | Therapsida

|

| Clade: | Cynodontia

|

| Clade: | Prozostrodontia |

| Clade: | Mammaliamorpha |

| Clade: | Mammaliaformes Rowe, 1988 |

| Subgroups | |

| |

Mammaliaformes ("mammalian forms") is a

Mammaliaformes is a term of

Animals in the Mammaliaformes clade are often called mammaliaforms, without the e. Sometimes, the spelling mammaliforms is used. The origin of

Mammaliaformes in life

Early mammaliaforms were generally

The early mammaliaforms did have a

It is possible that early mammaliaforms had

Like monotremes today, the legs of early mammaliaforms were somewhat sprawling, giving a rather "reptilian" type of gait. However, there was a general tendency to have more erect forelimbs, forms like

Hadrocodium lacks the multiple bones in its lower jaw seen in reptiles. These are still retained, however, in earlier mammaliaforms.[18]

With the possible exception of

Phylogeny

The cladogram below follows the analysis of Luo and colleagues in 2015.[22]

| Mammaliamorpha |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Expanded from above

| Trechnotheria |

| ||||||

Cladogram based on Rougier et al. (1996)[23] with Tikitherium included following Luo and Martin (2007).[3]

| Mammaliamorpha |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- S2CID 83999660.

- ^ .

- ^ S2CID 29846648. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- S2CID 131236175.

- ISBN 978-0-471-38461-8.

- ISSN 0102-9010.

- ^ Panciroli E., Benson RBJ., and Walsh S. 2017. The dentary of Wareolestes rex (Megazostrodontidae): a new specimen from Scotland and implications for morganucodontan tooth replacement. Papers in Palaeontology

- .

- S2CID 25806501.

- .

- S2CID 46067702.

- ^ "Your Inner Fish: Episode Guide". PBS. 2014. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

- ^ PMID 21969685.

- S2CID 21055062.

- ISBN 0-231-11918-6.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ Kielan−Jaworowska, Z. and Hurum, J.H. 2006. Limb posture in early mammals: Sprawling or parasagittal. Acta Palae− ontologica Polonica 51 (3): 393–406.

- ^ Hurum, J.H.; Luo, Z-X; Kielan-Jaworowska, Z. (2006). "Were mammals originally venomous?" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 51 (1): 1–11.

- ISBN 0-19-850760-7.

- ^ Jason A. Lillegraven, Zofia Kielan-Jaworowska, William A. Clemens, Mesozoic Mammals: The First Two-Thirds of Mammalian History, University of California Press, 17/12/1979 - 321

- · Source: PubMed

- ^ Michael L. Power, Jay Schulkin. The Evolution Of The Human Placenta. pp. 68–.

- PMID 26630008.

- ISSN 0003-0082.