Čedomilj Mijatović

Count Čedomilj Mijatović Чедомиљ Мијатовић | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister of Finance | |

| In office 1873–1874 1875 1880–1883 1886–1887 1888–1889 1894 | |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 1880–1881 1888–1889 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 17, 1842 Belgrade, Principality of Serbia |

| Died | May 14, 1932 (aged 89) London, United Kingdom |

| Political party | SNS |

| Spouse | Elodie Lawton |

| Signature | |

| Nickname | Čedo |

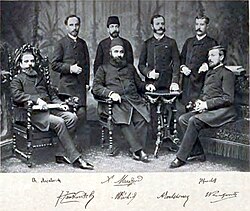

Count[1] Čedomilj Mijatović (Serbian Cyrillic: Чедомиљ Мијатовић; 17 October 1842 – May 14, 1932) was a Serbian statesman, economist, historian, writer and diplomat.

Mijatović served as the

Biography

Early life and education

His father Milan (1805–1852) was a lawyer who came to Serbia from the southern part of the Austrian Empire and became a teacher of Latin, history, and geography in Belgrade's First Gymnasium (Grammar School). However, Čedomilj Mijatović was primarily influenced by his mother, Rakila Kristina (1826–1901), who was of mixed Serbian-Spanish origin.

Mijatović studied a combination of economic courses and sciences in Munich, Zurich and Leipzig between 1863 and 1865 and completed his education by gaining experience from the National Bank of Austria and Kredit Anstalt in Vienna. He was a student of Lorenz von Stein and Karl Heinrich Rau and also accepted in his book theses the influences of Frédéric Bastiat and Henry Charles Carey.[2] During his studies in Germany, he met his future British wife Elodie Lawton (1825–1908), previously a dedicated abolitionist in Boston, who influenced him significantly, and turned him into a devoted Anglophile. She was the first English-speaking female historian in Serbia and she published The History of Modern Serbia in 1872. Later she published a collection of Serbian folk short stories and a collection of Serbian epic poems.[3]

At the age of 23, he became a professor at the Belgrade's

Efforts to reform the Serbian Orthodox Church

Miјatović's wife was a member of the Wesleyan Church and was able to imbue her husband with nonconformist religious devotion. However, he always remained faithful to the Serbian Orthodox Church but wanted to bring some religious zeal into it. That was not a very popular task in Serbia of his time. He found a collaborator in this endeavor in the person of a Belgrade priest Aleksa Ilić who established a religious monthly Hrishchanski Vesnik (Christian Messenger, in Serbian Cyrillic: Хришћански весник), the first journal dedicated to a religious revival in Serbia. A Scottish philanthropist Francis Mackenzie who settled in Belgrade helped this project materially and Miјatović remained one of the main contributors of the journal.

He was the most active and influential Serbian translator from English during the 19th century. The bibliography of his translations includes about a dozen titles. Most of them deal with religious topics. That was his effort to contribute to a religious revival. His translations into Serbian include sermons of well-known British preachers such as Dr.

Miјatović as cabinet minister

At the age of thirty-one, he was already Minister of Finance at the end of 1873. He started his career as a protégé of the leader of the subsequent Liberal Party,

The group of young conservatives he joined established the newspaper Videlo and soon came to power in October 1880. In the Government of Milan Piroćanac, Mijatović got two tenures. He was Minister of Foreign Affairs for the fourth time and Minister of Finance. Being a close friend of the ruler and in control of the two key ministries, he was considered by many diplomats as the most influential person of this Cabinet. Prince Milan used him for the most significant missions. The two decisions that shaped Serbia's history for many years were carried out by Mijatović.

When modern political parties were created in Serbia, in 1881, the Progressive Party turned out to be the only of the three Serbian parties (the other two being the mostly pro-Russian Liberal Party and very pro-Russian Radical Party) that was ready to make an agreement with Austria-Hungary, which became the most influential country in Serbia after the Congress of Berlin in 1878. The ruler decided to open a new page in Serbian foreign policy and arranged that a secret convention should be signed with the Habsburg monarchy. Mijatović was gradually entrusted by the ruler to complete this task and on June 28, 1881, he signed the Secret Convention by which Serbia got the diplomatic and political backing of the Habsburg Empire but abandoned her independence in the field of Foreign Policy.[4] When the two other most prominent members of the Cabinet, Prime Minister Piroćanac and Home Minister Garašanin learned about the exact contents of the Convention they decided to resign but had to accept the new reality in the end. In return, Mijatović had to resign his post as Minister of Foreign Affairs and kept only his tenure at the Ministry of Finance. His last act as Minister of Foreign Affairs was to sign a Consular Convention and a Commercial Agreement with the United States of America on October 14. 1881. During talks that preceded the signing of the Secret Convention Mijatović was well received in Vienna by the Emperor Francis Joseph and other dignitaries of the Empire. The Emperor later decorated him with the first class of the Order of the Iron Crown, which entitled its bearer to become an Austro-Hungarian count. Serbian citizens were banned by the Serbian constitution to accept any nobility titles. It is not clear if Mijatović ever officially submitted an application to become an Austro-Hungarian count, yet he used this title openly since 1915, being the only Serb from the Kingdom of Serbia who did it.

Affair with Union Général

As the Minister of Finance Mijatović had to secure Serbia's commitments from the Berlin Treaty by which she undertook to build the part of the Vienna-Constantinople railway line that went through Serbia. Since Serbia could not finance the project herself a proper foreign creditor had to be found and a Parisian financial society called Union Général was selected in 1881. Unfortunately, it faced bankruptcy as soon as the beginning of 1882, which brought the already shaky state of Serbian finances very close to complete disaster. Learning of the bankruptcy Mijatović urgently traveled to Paris and there supported by Austro-Hungarian diplomacy found a way out. Another financial house Comptoir national d'escompte de Paris (CNEP) took on the projects without detriment to Serbia. In spite of this success, the reputation of Mijatović's party suffered a serious blow and never recovered. It turned out that the agents of the Union Général in Belgrade had tried to bribe many MPs and politicians and the reputation of the Progressivists suffered the most from this. He took personal part in preparing a law on the establishment of the National Bank of Serbia that was passed by the Serbian Parliament in January 1883. He advocated the establishment of such an institution long before and had an opportunity to establish it during his tenure. The Government of the Progressivists resigned in October 1883.

Negotiator of the Peace Treaty at Bucharest

Being a lonely Serbian Anglophile Mijatović wished to be appointed as the first Serbian Minister in London, but had to wait until October 1884 when he became the second Serbian Minister at the Court of St James's. During this tenure, he came into contact with many influential persons but his diplomatic post in London soon ended since he was appointed to be the sole Serbian negotiator in Bucharest where peace negotiations were scheduled following the Serbo-Bulgarian War. Serbia attacked Bulgaria on November 14, 1885, and within two weeks suffered a humiliating defeat. It was thanks to the Secret Convention signed with Austria-Hungary that Serbia was able to get out of the war without suffering more serious consequences. In Bucharest Mijatović and the Bulgarian representative Ivan Evstratiev Geshov concluded, on March 3, 1886, one of the shortest treaties in diplomatic history with one article only: Article seul et unique. – L’état de paix qui a cessé d’exister entre le Royaume de Serbie et la Principauté du Bulgarie le 2–14 Novembre, 1885, est rétabli à partir de l’échange de ratification du present traité qui aura lieu à Bucharest. Mijatović proved to be a peacemaker since he had ignored instructions from Belgrade that were prepared in such a way that he was supposed to find an excuse for a new war. Apparently, Mijatović was more worried about what sort of reputation he would have in England if negotiations failed than about criticism from Belgrade for his conciliatory approach.

First self exile to London

Having returned from Bucharest Mijatović became for the fifth time Finance Minister in the Government of Milutin Garašanin in 1886/1887. Finally, in 1887/1889 he was for the second time Foreign Minister in the Government of Nikola Hristić (Hristić). In this capacity, he signed a renewal of the Secret Convention. However, the decision of King Milan to abdicate on March 6, 1889, effectively ended his special position at the Court. The new government encouraged persecution of the members of the Progressive Party. Faced with all these failures he decided to leave Serbia and withdrew to Britain in September 1889.

He found refuge in London where he spent years between 1889 and 1894 and was committed to writing novels in Serbian based on gothic novels of

Diplomatic career

In 1894 he returned from his self-exile to become Minister of Finance for the sixth and last time, but his tenure ended with the resignation of the whole Government after only two months in April 1894. He spent the rest of that year as a Serbian Minister in Bucharest but was recalled at the end of 1894. In April 1895 he got his favorite appointment. He became for the second time Serbian Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary at the Court of St James's and kept this position until 1900. During this mandate he represented Serbia at the

In the early morning of June 11, 1903, a conspiracy of Serbian officers killed King Alexander Obrenović and his unpopular wife Queen Draga. Having murdered them they threw their naked bodies out of a window. The new government consisted of regicides and it appointed Petar Karađorđević to be the new ruler of Serbia. The very event and composition of the new Cabinet caused widespread condemnation throughout Europe but only Britain and the Netherlands decided to break off diplomatic relations with Serbia. Mijatović was himself horrified and he was the only Serbian diplomat who resigned his post on June 22. This act was never forgiven to him by influential political circles in Belgrade.

Mijatović's name became known around the world thanks to a clairvoyant session that he attended together with a famous Victorian journalist

After the May Coup Mijatović stayed in London until the end of his life, though he tendered his resignation when the new Serbian government was formed in 1903. Mijatović was replaced by diplomat Aleksandar Jovičić (1856-1934).[9] In 1908 he published his most popular book in English that went through three British and three American editions entitled Servia and the Servians.[10] His reputation in Serbia after 1903 suffered greatly due to false rumors that he was implicated in a conspiracy to bring Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn, beloved son of Queen Victoria, to the throne of Serbia. In 1911 he met King Peter Karageorgević in Paris and from this moment he was fully reconciled with the new regime in Serbia. Therefore, it is not surprising that he was considered as an unofficial member of the Serbian delegation in London during the London Conference in December 1912. Being a widower from 1908 he was considered as a favorite candidate of both the Serbian Government and the King to become the Archbishop of Skopje, which had two years earlier been incorporated to the Serbian state. But these efforts failed.

He became very active again at the beginning of the

He died in London on May 14, 1932.[12]

He was awarded Order of the White Eagle, Legion of Honour, Order of the Cross of Takovo and a number of other decorations.[13]

Works in English

He published 19 books in Serbian, and 6 books in English:

- Constantine, the Last Emperor of the Greeks or the Conquest of Constantinople by the Turks (A.D. 1453), the first Serbian contribution to Byzantine history in English; after the Latest Historical Researches (London: Sampson Low, Marston & Company, 1892)

- Ancestors of the House of Orange (1892)[14]

- A Royal Tragedy. Being the Story of the Assassination of King Alexander and Queen Draga of Servia (London: Eveleigh Nash, 1906)

- Servia and the Servians (London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, 1908)

- A Short History of Russia and the Balkan States, authored with Sir Donald Mackenzie Wallace, Prince Kropotkin and J. D. Bourchier (London: The Encyclopædia Britannica Company, 1914)

- The Memoirs of a Balkan Diplomatist (London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne: Cassell and Co., 1917)

His book Servia and the Servians together with his entries on Serbia in the Tenth and Eleventh editions of the Encyclopædia Britannica served a very important purpose of offering a favourable view of Serbia to the Anglo-American public at the beginning of the twentieth century in a very turbulent and decisive period for Serbia. He was arguably among the first Serbs to contribute to the Encyclopædia Britannica and some of his entries were reproduced up until 1973. The other was Prince Bojidar Karageorgevitch.

Assessment

His long life in Britain made him a cultural bridge between the two nations. His role in British-Serbian relations is unmatched in terms of his influence on mutual relations. Many British Balkan experts were aware of this and had a very high opinion of Mijatović.

His whole working life was strongly influenced by the culture of Victorian Britain. In introducing Gothic novels into Serbian literature he was influenced by

See also

References

- Adapted from Jovan Skerlić, Istorija nove srpske književnosti / History of Modern Serbian Literature (Belgrade, 1914) pages 339-342

- ^ "A Few Notes About Grants of Titles of Nobility by Modern Serbian Monarchs". www.academia.edu. January 2019. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ISBN 9780857726056.

- ^ Elodie Lawton Mijatovics, The History of Modern Serbia (London: William Tweedie, 1872); (Elodie Lawton Mijatovics), Serbian Folk-lore. Popular tales selected and translated by Madam Csedomilj Mijatovics (London: W. Isbister & Co, 1874); Madame Elodie Lawton Mijatovics, Kosovo: an Attempt to bring Serbian National Songs, about the Fall of the Serbian Empire at the Battle of Kosovo, into one Poem (London: W. Isbister, 1881).

- ^ Serbia, RTS, Radio televizija Srbije, Radio Television of. "Чедомиљ Мијатовић - и Косово и Енглеска". www.rts.rs. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Chedomil Mijatovich, Constantine the last Emperor of the Greeks; or the Conquest of Constantinople by the Turks (A. D. 1453). After the latest Historical Researches (London: Sampson Low, Marston, and Co., 1892). The book was later translated into Russian and Spanish.

- ^ "No. 27516". The London Gazette. January 16, 1903. p. 305.

- ^ W. T. Stead, 'A Clairvoyant Vision of the Assassination at Belgrade', Review of Reviews, vol. 28 (1903), p. 31.

- ^ See The Westminster Gazette, June 11, 1903, p. 7 b; The New York Times, June 12, 1903, p. 2 c ('A Clairvoyant's Prediction').

- ISBN 9782911527012.

- ^ Chedo Mijatovich, Servia and the Servians (London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, 1908). The second British edition: Chedo Mijatovich, Servia of the Servians (London: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, 1911). The third British edition: Chedo Mijatovich, Servia of the Servians (London, Bath, New York, and Melbourne: Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, 1915). American editions: Chedo Mijatovich, Servia and the Servians (Boston: L.C. Page & company, 1908); Chedo Mijatovich, Servia of the Servians (New edit., New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1913); Chedo Mijatovich, Servia of the Servians (New ed., New York: Scribner, 1914).

- ^ "Serbia's Aged Envoy talks of his Nation", The New York Times, January 23, 1916, p. SM 4.

- ^ The Times, Monday, May 16, 1932, стр. 12, d ("Count Miyatovitch. Thrice Serbian Minister in London."); The Times, Saturday, May 21, 1932, стр. 13, b ("Funeral and Memorial Services. Count Miyatovitch"). Cf. "Count Miyatovitch, Serb diplomat dies: wrote “World’s Shortest Peace Treaty” in 1886 ending the war between Serbia and Bulgaria”, The New York Times, May 15, 1932, p. N5.

- ^ Acović, Dragomir (2012). Slava i čast: Odlikovanja među Srbima, Srbi među odlikovanjima. Belgrade: Službeni Glasnik. pp. 94, 565.

- ^ No sample is known to have survived of the book: Ancestors of the House of Orange, 1892. The title is known from biographical lexicons: S. v. “Mijatovich, Chedomille”, Who Was Who 1929–1940, A Companion to Who’s Who containing the Biographies of those who Died during the Period 1929–1940 (London: Adam and Charles Black, 1980), vol. III, p. 939; S. v. “Mijatovich, Tjedomil”, Enciclopedia Universal Ilustrada Europeo-Americana, tomo XXXV, Madrid, 1958, p. 153.

- ^ J. D. Bourchier, "The Great Servian Festival,” The Fortnightly Review, vol. 46 (1889), p. 219; cf. Lady Grogan, The Life of J. D. Bourchier (London: Hurst and Blackett Ltd., 1926), p. 89.

- ^ W. T. Stead, “Members of the Parliament of Peace,” The Review of Reviews, vol. 19 (1899), p. 533.

- ^ W. T. Stead, “A Clairvoyant Vision of the Assassinations at Belgrade,” The Review of Reviews, vol. 28 (July 1903), p. 31.

- ^ The Times, November 12, 1889, p. 5.

- ^ Janković, Ivan (November 30, 2004). "Filozofska kontrarevolucija Edmunda Berka – Katalaksija". Retrieved March 1, 2021.

Bibliography

- Count Chedomille Mijatovich, The Memoirs of a Balkan Diplomatist (London, New York, Toronto and Melbourne: Cassel and Co., 1917).

- Uroš Džonić, "Čedomilj Mijatović", Godišnjica Nikole Čupića, vol. XLII (1933), pp. 190–212.

- Slobodan Jovanović, Vlada Milana Obrenovića (The Rule of Milan Obrenović), in 2 vol., Belgrade, 1926 and 1927.

- Slobodan Jovanović, Vlada Aleksandra Obrenovića (The Rule of Aleksandar Obrenović), collected works, vol. 12, Belgrade: Geca Kon, 1936.

- Simha Kabiljo-Šutić, Posrednici dveju kultura. Studije o srpsko-engleskim književnim i kulturnim vezama (Mediators between two Cultures. Studies on Serbian-English Literary and Cultural Relations), Belgrade: Institut za književnost i jezik, 1989.

- Slobodan G. Markovich, British Perceptions of Serbia and the Balkans, 1903–1906 (Paris: Dialogue, 2000). ANSES at www.anses.rs...

- Slobodan G. Marković, Grof Čedomilj Mijatović. Viktorijanac među Srbima (Count Chedomille Mijatovich. A Belgrade Law SchoolPress, 2006.

- Slobodan G. Marković, Čedomilj Mijatović. A bridge between two Cultures, Chevening Journal, No. 21 (2006), pp. 42–43. (Archive index at the Wayback Machine)

- Predrag Protić, Sumnje i nadanja, Prilozi proučavanju duhovnih kretanja kod Srba i vreme romantizma (Doubts and Hopes. Contribution to the study of ideas among Serbs in the era of Romanticism), Belgrade: Prosveta, 1986.

- Marković Slobodan G. (2007). "Čedomilj Mijatović, a leading Serbian Anglophile" (PDF). Balcanica (38): 105–132. .

External links

![]() Works by or about Čedomilj Mijatović at Wikisource

Works by or about Čedomilj Mijatović at Wikisource