Serbian Orthodox Church

Macedonian Orthodox Church Montenegrin Orthodox Church | |

|---|---|

| Members | 8[2] to 12 million[3] |

| Other name(s) |

|

| Official website | spc |

| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

| Overview |

The Serbian Orthodox Church (

The majority of the population in

The Church achieved

History

Early Christianity

Christianity started to spread throughout the

In 395, the Empire was divided, and its eastern half later became known as the Byzantine Empire. In 535, emperor Justinian I created the Archbishopric of Justiniana Prima, centered in the emperor's birth-city of Justiniana Prima, near modern Lebane in Serbia. The archbishopric had ecclesiastical jurisdiction over all provinces of the Diocese of Dacia.[14][15] By the beginning of the 7th century, Byzantine provincial and ecclesiastical order in the region was destroyed by invading Avars and Slavs. The church life was renewed in the same century in the province of Illyricum and Dalmatia after a more pronounced Christianization of the Serbs and other Slavs by the Roman Church.[16][17][18] [19] In the 7th and mid-8th century the area was not under jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Constantinople.[20]

Christianization of Serbs

The history of the early medieval Serbian Principality is recorded in the work De Administrando Imperio (DAI), compiled by the Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (r. 913–959). The DAI drew information on the Serbs from, among others, a Serbian source.[22] The Serbs were said to have received the protection of Emperor Heraclius (r. 610–641), and Porphyrogenitus stressed that the Serbs had always been under Imperial rule. According to De Administrando Imperio, the center from which the Serbs received their baptism was marked as Rome.[23] His account on the first Christianization of the Serbs can be dated to 632–638; this might have been Porphyrogenitus' construction, or may have encompassed a limited group of chiefs, with lesser reception by the wider layers of the tribe.[24] From the 7th until mid-9th century, the Serbs were under influence of the Roman Church.[25] The initial ecclesiastical affiliation with a specific diocese is uncertain, probably was not an Adriatic centre.[26] Early medieval Serbs are accounted as Christian by 870s,[27] but it was a process that ended in the late 9th century during the time of Basil I,[28] and medieval necropolises until the 13th century in the territory of modern Serbia show an "incomplete process of Christianization" as local Christianity depended on the social structure (urban and rural).[29]

The expansion of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople over the Praetorian prefecture of Illyricum is considered to have begun in 731 by Emperor Leo III when he annexed Sicily and Calabria,[30][31] but whether the Patriarchate also expanded into the eastern parts of Illyricum and Dalmatia is uncertain and a matter of scholarly debate.[32] The expansion most definitely happened since the mid-9th century,[20] when the Byzantines emperors and patriarch demanded that the Church administrative borders follow political borders.[25] In the same century, the region was also politically contested between the Carolingian Empire and Byzantine Empire.[33] The most influential and successful was emperor Basil I, who actively worked on gaining control over all the Praetorian prefecture of Illyricum (from Greek, Bulgarian, Serbian to Croatian Slavic peoples).[34][35][36][37] Basil I likely sent at least one embassy to Mutimir of Serbia,[38] who decided to maintain the communion of Church in Serbia with the Patriarchate of Constantinople when Pope John VIII invited him to get back to the jurisdiction of the bishopric of Sirmium (see also Archbishopric of Moravia) in a letter dated to May 873.[39][40][41]

With Christianization in the 9th century, Christian names appear among the members of Serbian dynasties (Petar, Stefan, Pavle, Zaharije).

Archbishopric of Ohrid (1018–1219)

Following his

The 10th- or 11th-century Gospel Book

Autocephalous Archbishopric (1219–1346)

Serbian prince

Saint Sava returned to the Holy Mountain in 1217/18, preparing for the formation of an

The following seats were newly created in the time of Saint Sava:

- Žiča, the seat of the Archbishop at Monastery of Žiča;

- region;

- Humregion;

- Eparchy of Dabar (Dabarska), seated at Monastery of St. Nicholas in Dabar (region);

- Eparchy of Moravica (Moravička), seated at Monastery of St. Achillius in Moravica župa;

- Monastery of St. George in Budimljaregion;

- Eparchy of Toplica (Toplička), seated at Toplicaregion;

- Eparchy of Hvosno (Hvostanska), seated at ).

Older eparchies under the jurisdiction of the Serbian Archbishop were:

- region;

- Lipljan in Kosovo;

- .

In 1229/1233, Saint Sava went on a pilgrimage to

Saint Sava died in

In 1253 the see was transferred to the

Medieval Patriarchate (1346–1463)

The status of the Serbian Orthodox Church grew along with the expansion and heightened prestige of the Serbian kingdom. After King Stefan Dušan assumed the imperial title of tsar, the Serbian Archbishopric was correspondingly raised to the rank of Patriarchate in 1346. In the century that followed, the Serbian Church achieved its greatest power and prestige. In the 14th century Serbian Orthodox clergy had the title of Protos at Mount Athos.

On 16 April 1346 (

In 1375, an agreement between the Serbian Patriarchate and the Patriarchate of Constantinople was reached.[81] The Battle of Kosovo (1389) and its aftermath had a lasting influence on medieval legacy and later traditions of the Serbian Orthodox Church.[82] In 1455, when Ottoman Turks conquered the Patriarchal seat in Peć, Patriarch Arsenije II found temporary refuge in Smederevo, the capital city of Serbian Despotate.[83]

Among cultural, artistic and literary legacies created under the auspices of the Serbian Orthodox Church during the medieval period were

Renewed Patriarchate (1557–1766)

The

After several failed attempts, made from c. 1530 up to 1541 by metropolitan

In the time of Serbian Patriarch

After consequent Serbian uprisings against the Turkish occupiers in which the church had a leading role, the Ottomans abolished the Patriarchate once again in 1766.[9] The church returned once more under the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople. This period of rule by the so-called "Phanariots" was a period of great spiritual decline[citation needed] because the Greek bishops had very little understanding of their Serbian flock.

Church in the Habsburg Monarchy

During this period, Christians across the Balkans were under pressure to convert to Islam to avoid severe taxes imposed by the Turks in retaliation for uprisings and continued resistance. The success of Islamization was limited to certain areas, with the majority of the Serbian population keeping its Christian faith despite the negative consequences. To avoid them, numerous Serbs migrated with their hierarchs to the Habsburg monarchy where their autonomy had been granted. In 1708, an autonomous Serbian Orthodox Metropolitanate of Karlovci was created, which would later become a patriarchate (1848–1920).[89]

During the reign of Maria Theresa (1740-1780), several assemblies of Orthodox Serbs were held, sending their petitions to the Habsburg court. In response to that, several royal acts were issued, such as Regulamentum privilegiorum (1770) and Regulamentum Illyricae Nationis (1777), both of them replaced by the royal Declaratory Rescript of 1779, that regulated various important questions, from the procedure regarding the elections of Serbian Orthodox bishops in the Habsburg Monarchy, to the management of dioceses, parishes and monasteries. The act was upheld in force until it was replaced by the "Royal Rescript" issued on 10 August 1868.[90]

Modern history

The church's close association with Serbian resistance to Ottoman rule led to Eastern Orthodoxy becoming inextricably linked with Serbian national identity and the new Serbian monarchy that emerged from 1815 onwards. The Serbian Orthodox Church in the Principality of Serbia gained its autonomy in 1831 and was organized as the Metropolitanate of Belgrade, remaining under the ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. [11] The Principality of Serbia gained full political independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1878, and soon after those negotiations were initiated with the Ecumenical Patriarchate, resulting in canonical recognition of full ecclesiastical independence (autocephaly) for the Metropolitanate of Belgrade in 1879.[91]

At the same time, Serbian Orthodox eparchies in Bosnia and Herzegovina remained under the supreme ecclesiastical jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, but after the Austro-Hungarian occupation (1878) of those provinces, local eparchies gained internal autonomy, regulated by the Convention of 1880, signed by representatives of Austro-Hungarian authorities and the Patriarchate of Constantinople.[92][93]

In the southern eparchies, that remained under the Ottoman rule, Serbian metropolitans were appointed by the end of the 19th century.

During the World War I (1914–1918), the Serbian Orthodox Church suffered massive casualties.[95]

Reunification

After the liberation and political unification, that was achieved by creation of the

The united Serbian Orthodox Church kept under its jurisdiction the

During the

Under communist rule

After the war, the church was suppressed by the

In 1963, the Serbian Church among the diaspora was reorganized, and the eparchy for the United States and Canada was divided into three separate eparchies. At the same time, some internal divisions sparked in the Serbian diaspora, leading to the creation of the separate "Free Serbian Orthodox Church" under

The gradual demise of Yugoslav communism and the rise of rival nationalist movements during the 1980s also led to a marked religious revival throughout Yugoslavia, not least in Serbia. The

Since the establishment of the Yugoslav federal unit of "

Similar plans for the creation of an independent church in the Yugoslav federal unit of Montenegro were also considered, but those plans were not put into action before 1993, when the creation of the Montenegrin Orthodox Church was proclaimed. The organization was not legally registered before 2000, receiving no support from the Eastern Orthodox communion, and succeeding to attract only a minority of Eastern Orthodox adherents in Montenegro.[106][107]

Recent history

The

Many churches in

The eparchies of Bihać and Petrovac, Dabar-Bosnia and Zvornik and Tuzla were also dislocated due to the

Right: Devič monastery after it was burned down in 2004 unrest in Kosovo

By 1998, the situation had stabilized in both countries. The clergy and many of the faithful returned; most of the property of the Serbian Orthodox Church was returned to normal use and damaged and destroyed properties were restored. The process of rebuilding several churches is still underway,[

Owing to the

The process of church reorganization among the diaspora and full reintegration of the Metropolitanate of New Gračanica was completed from 2009 to 2011. By that, full structural unity of Serbian church institutions in the diaspora was achieved.

Adherents

Based on the official census results in countries that encompass the territorial canonical jurisdiction of the Serbian Orthodox Church (the Serb autochthonous region of Western Balkans), there are more than 8 million adherents of the church. Orthodoxy is the largest single religious faith in Serbia with 6,079,296 adherents (84.5% of the population) according to the 2011 census,[110] and in Montenegro with around 320,000 (51% of the population). It is the second-largest faith in Bosnia and Herzegovina with 31.2% of the population, and in Croatia with 4.4% of the population. Figures for eparchies abroad (Western Europe, North America, and Australia) are unknown although some estimates can be reached based on the size of the Serb diaspora, which numbers over two million people.

Structure

The head of the Serbian Orthodox Church, the patriarch, also serves as the head (metropolitan) of the Metropolitanate of Belgrade and Karlovci. The current patriarch, Porfirije, was inaugurated on 19 February 2021. Serbian Orthodox patriarchs use the style His Holiness the Archbishop of Peć, Metropolitan of Belgrade and Karlovci, Serbian Patriarch.

The highest body of the Serbian Orthodox Church is the Bishops' Council. It consists of the Patriarch, the Metropolitans, Bishops, Archbishop of Ohrid and Vicar Bishops. It meets annually – in spring. The Bishops' Council makes important decisions for the church and elects the patriarch.

The executive body of the Serbian Orthodox Church is the Holy Synod. It has five members: four bishops and the patriarch.[111] The Holy Synod takes care of the everyday operation of the church, holding meetings on regular basis.

Territorial organisation

The territory of the Serbian Orthodox Church is divided into:[112][113]

- 1 patriarchal Serbian Patriarch

- 4 metropolitanates, headed by metropolitans

- 35

- 1 autonomous archbishopric, headed by archbishop, the Autonomous Archbishopric of Ohrid. It is further divided into 1 eparchy headed by the metropolitan and 6 eparchies headed by bishops.

Dioceses are further divided into episcopal

Autonomous Archbishopric of Ohrid

The

Doctrine and liturgy

The Serbian Orthodox Church upholds the

Liturgical traditions and practices of the Serbian Orthodox Church are based on the Eastern Orthodox worship.[115] Services cannot properly be conducted by a single person but must have at least one other person present. Usually, all of the services are conducted on a daily basis only in monasteries and cathedrals, while parish churches might only do the services on the weekend and major feast days. The Divine Liturgy is the celebration of the Eucharist. The Divine Liturgy is not celebrated on weekdays during the preparatory season of Great Lent. Communion is consecrated on Sundays and distributed during the week at the Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts. Services, especially the Divine Liturgy, can only be performed once a day on any particular altar.[citation needed]

A key part of the Serbian Orthodox religion is the

Social issues

The Serbian Orthodox Church upholds traditional views on modern social issues,[116] such as separation of church and state (imposed since the abolition of monarchy in 1945), and social equality.[117] Since all forms of priesthood are reserved only for men, the role of women in church administration is limited to specific activities, mainly in the fields of religious education and religious arts, including the participation in various forms of charity work.[118]

Inter-Christian relations

The Serbian Orthodox Church is in full communion with the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople (which holds a special place of honour within Eastern Orthodoxy and serves as the seat for the Ecumenical Patriarch, who enjoys the status of first-among-equals) and all of the mainstream autocephalous Eastern Orthodox church bodies except the Orthodox Church of Ukraine. It has been a member of the World Council of Churches since 1965,[119] and of the Conference of European Churches.

Art

Architecture

Serbian medieval churches were built in the Byzantine spirit. The

During the 17th-century, many of the Serbian Orthodox churches that were built in Belgrade took all the characteristics of baroque churches built in the Habsburg-occupied regions where Serbs lived. The churches usually had a bell tower, and a single nave building with the iconostasis inside the church covered with Renaissance-style paintings. These churches can be found in Belgrade and Vojvodina, which were occupied by the Austrian Empire from 1717 to 1739, and on the border with Austrian (later Austria-Hungary) across the Sava and Danube rivers from 1804 when Serbian statehood was re-established.

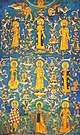

Icons

Icons are replete with symbolism meant to convey far more meaning than simply the identity of the person depicted, and it is for this reason that Orthodox iconography has become an exacting science of copying older icons rather than an opportunity for artistic expression. The personal, idiosyncratic and creative traditions of Western European religious art are largely lacking in Orthodox iconography before the 17th century, when Russian and Serbian icon painting was influenced by religious paintings and engravings from Europe.

Large icons can be found adorning the walls of churches and often cover the inside structure completely. Orthodox homes often likewise have icons hanging on the wall, usually together on an eastern facing wall, and in a central location where the family can pray together.

Insignia

The Serbian tricolour with a Serbian cross is used as the official flag of the Serbian Orthodox Church, as defined in the Article 4 of the SOC Constitution.[111]

A number of other unofficial variant flags, some with variations of the cross, coat of arms, or both, exist.[clarification needed]

See also

- List of heads of the Serbian Orthodox Church

- List of eparchies of the Serbian Orthodox Church

- List of Serbian Orthodox monasteries

- List of Serbian saints

References

- ^ Serbian Orthodox Church at World Council of Churches

- ^ World Council of Churches: Serbian Orthodox Church

- ^ Johnston & Sampson 1995, p. 330.

- ^ Radić 2007, p. 231–248.

- ^ Fotić 2008, p. 519–520.

- ^ "His Holiness Porfirije, Archbishop of Pec, Metropolitan of Belgrade and Karlovci and Serbian Patriarch enthroned". Serbian Orthodox Church [Official web site]. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 28.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 64-65.

- ^ a b Ćirković 2004, p. 177.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 149-151.

- ^ a b Ćirković 2004, p. 192-193.

- ^ a b Radić 2007, p. 235-236.

- ^ Popović 1996.

- ^ Curta 2001, p. 77.

- ^ Turlej 2016, p. 189.

- ^ Curta 2001, p. 125, 130.

- ^ Živković 2013a, pp. 47.

- ^ Komatina 2015, pp. 713.

- ^ Komatina 2016, pp. 44–47, 73–74.

- ^ a b Komatina 2016, pp. 47.

- ^ Živković 2007, p. 23–29.

- ^ Živković 2010, p. 117–131.

- ^ Živković 2010, p. 121.

- ^ Živković 2008, pp. 38–40.

- ^ a b Komatina 2016, pp. 74.

- ^ Komatina 2016, pp. 397.

- ^ Živković 2013a, pp. 35.

- ^ Komatina 2016, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Špehar 2010, pp. 216.

- ^ Fine 1991, p. 116.

- ^ Treadgold 1997, p. 354–355.

- ^ Komatina 2016, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Živković 2013a, pp. 38.

- ^ Živković 2013a, pp. 46–48.

- ^ Komatina 2015, pp. 712, 717.

- ^ Komatina 2016, pp. 47–50, 74.

- ^ Špehar 2010, pp. 203.

- ^ Živković 2013a, pp. 46.

- ^ Živković 2013a, pp. 44–46.

- ^ Komatina 2015, pp. 713, 717.

- ^ Komatina 2016, pp. 73.

- ^ a b c Vlasto 1970, p. 209.

- ^ Živković 2013a, pp. 45.

- ^ Komatina 2015, pp. 715.

- ^ Komatina 2015, pp. 716.

- ^ Živković 2013a, pp. 48.

- ^ Komatina 2015, pp. 717.

- ^ Komatina 2016, pp. 76, 89–90.

- ^ Popović 1999, p. 38.

- ^ Popović 1999, p. 401.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, pp. 20, 30.

- ^ Komatina 2016, pp. 76–77, 398.

- ^ Komatina 2016, pp. 75, 88–91.

- ^ Komatina 2015, pp. 717–718.

- ^ Komatina 2016, pp. 77, 91.

- ^ Špehar 2010, pp. 203, 216.

- ^ a b Vlasto 1970, p. 208.

- ^ Fine 1991, p. 141.

- ^ Fine 1991, pp. 141–142.

- ^ Prinzing 2012, pp. 358–362.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 20, 40.

- ^ Stephenson 2000, p. 75.

- ^ Jagić 1883.

- ^ Vlasto 1970, p. 218.

- ^ a b Ćirković 2004, p. 33.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 35-36.

- ^ Kalić 2017, p. 7-18.

- ^ Ferjančić & Maksimović 2014, p. 37–54.

- ^ Marjanović 2018, p. 41–50.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 43, 68.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 43.

- ^ Vlasto 1970, pp. 222, 233.

- ^ Čanak-Medić & Todić 2017.

- ^ Pavlowitch 2002, p. 11.

- ^ Vásáry 2005, p. 100-101.

- ^ Ljubinković 1975, p. VIII.

- ^ Ćurčić 1979.

- ^ Todić & Čanak-Medić 2013.

- ^ Pantelić 2002.

- ^ Fine 1994, pp. 309–310.

- ^ Fine 1994, p. 387-388.

- ^ Šuica 2011, p. 152-174.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 107, 134.

- ^ Birnbaum 1972, p. 243–284.

- ^ Thomson 1993, p. 103-134.

- ^ Ivanović 2019, p. 103–129.

- ^ Daskalov & Marinov 2013, p. 29.

- ^ Sotirović 2011, p. 143–169.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 149-151, 166-167.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 166-167, 196-197.

- ^ Kiminas 2009, p. 20-21.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 231.

- ^ Tomić 2019, p. 1445-1465.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 244.

- ^ Radić 2015, pp. 263–285.

- ^ Vuković 1998.

- ^ Stojanović 2017, p. 269–287.

- ^ Velikonja 2003, p. 170.

- ^ Stojanović 2017, p. 275.

- ^ a b Bećirović, Denis (2010). "Komunistička vlast i Srpska Pravoslavna Crkva u Bosni i Hercegovini (1945-1955) - Pritisci, napadi, hapšenja i suđenja" (PDF). Tokovi Istorije (3): 76–78.

- ^ .Vukic, Neven. 2021. “The Church in a Communist State: Justin Popovic (1894–1979) and the Struggle for Orthodoxy in Serbia/Yugoslavia.” Journal of Church & State 63 (2): 278–99.

- ^ Spasović 2004, p. 124-129.

- ISBN 978-0-73695-291-0.

- ^ Slijepčević 1958, p. 224, 242.

- ^ Radić 2007, p. 236.

- ^ Radić 2007, p. 247.

- ^ Morrison & Čagorović 2014, p. 151-170.

- ^ Bataković 2017, p. 116.

- ^ Bataković 2007, p. 255-260.

- ^ Branka Pantic; Arsic Aleksandar; Miroslav Ivkovic; Milojkovic Jelena. "Republicki zavod za statistiku Srbije". Archived from the original on 3 February 2015. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ^ a b Constitution of the Serbian Orthodox Church

- List of Eparchies of the Serbian Orthodox Church

- ^ Official SPC site: Eparchies Links (in Serbian)

- ^ Jovanović 2019, p. 169-187.

- ^ Ubiparipović 2019, p. 258-267.

- ^ Radić & Vukomanović 2014, p. 180-211.

- ^ Kuburić 2014, p. 399.

- ^ Abramović 2019, p. 243-262.

- ^ "Serbian Orthodox Church". World Council of Churches. January 1965. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

Sources

- Abramović, Anja (2019). "Women's Issues in Serbian Orthodox Church". Religion and Tolerance: Journal of the Center for Empirical Researches of Religion. 17 (32): 243–262.

- Andrić, Stanko (2016). "Saint John Capistran and Despot George Branković: An Impossible Compromise". Byzantinoslavica. 74 (1–2): 202–227.

- ISBN 9782825119587.

- Bataković, Dušan T. (2007). "Surviving in Ghetto-like Enclaves: The Serbs of Kosovo and Metohija 1999-2007" (PDF). Kosovo and Metohija: Living in the Enclave. Belgrade: Institute for Balkan Studies. pp. 239–263.

- Bataković, Dušan T. (2017). "The Case of Kosovo: Separation vs. Integration: Legacy, Identity, Nationalism". Studia Środkowoeuropejskie i Bałkanistyczne. 26: 105–123.

- Birnbaum, Henrik (1972). "Byzantine Tradition Transformed: The Old Serbian Vita". Aspects of the Balkans: Continuity and Change. The Hague and Paris: Mouton. pp. 243–284.

- Buchenau, Klaus (2014). "The Serbian Orthodox Church". Eastern Christianity and Politics in the Twenty-First Century. London-New York: Routledge. pp. 67–93. ISBN 9781317818663.

- Čanak-Medić, Milka; Todić, Branislav (2017). The Monastery of the Patriarchate of Peć. Novi Sad: Platoneum, Beseda. ISBN 9788685869839.

- Carter, Francis W. (1969). "An Analysis of the Medieval Serbian Oecumene: A Theoretical Approach". Geografiska Annaler. Series B: Human Geography. 51 (1–2): 39–56. .

- Ćirković, Sima; Korać, Vojislav; Babić, Gordana (1986). Studenica Monastery. Belgrade: Jugoslovenska revija.

- ISBN 9781405142915.

- .

- Crnčević, Dejan (2013). "Architecture of Cathedral Churches on the Eastern Adriatic Coast at the Time of the First Principalities of South Slavs (9th-11th Centuries)". The World of the Slavs: Studies of the East, West and South Slavs: Civitas, Oppidas, Villas and Archeological Evidence (7th to 11th Centuries AD). Belgrade: The Institute for History. pp. 37–136. ISBN 9788677431044.

- Ćurčić, Slobodan (1979). Gračanica: King Milutin's Church and Its Place in Late Byzantine Architecture. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 9780271002187.

- ISBN 9781139428880.

- ISBN 9780521815390.

- ISBN 9789004395190.

- Daskalov, Rumen; Marinov, Tchavdar, eds. (2013). Entangled Histories of the Balkans: Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies. BRILL. ISBN 9789004250765.

- Đorđević, Života; Pejić, Svetlana, eds. (1999). Cultural Heritage of Kosovo and Metohija. Belgrade: Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments of the Republic of Serbia. ISBN 9788680879161.

- Dragojlović, Dragoljub (1990). "Dyrrachium et les Évéchés de Doclea jusqu'a la fondation de l'Archevéche de Bar" (PDF). Balcanica (21): 201–209.

- Dragojlović, Dragoljub (1991). "Archevéché d'Ohrid dans la hiérarchie des grandes églises chrétiennes" (PDF). Balcanica (22): 43–55.

- Dragojlović, Dragoljub (1993). "Serbian Spirituality in the 13th and 14th Centuries and Western Scholasticism". Serbs in European Civilization. Belgrade: Nova, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies. pp. 32–40. ISBN 9788675830153.

- ISBN 9780813507996.

- .

- ISBN 0472081497.

- ISBN 0472082604.

- ISBN 0472025600.

- Fotić, Aleksandar (2008). "Serbian Orthodox Church". Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. New York: Infobase Publishing. pp. 519–520. ISBN 9781438110257.

- Gavrilović, Zaga (2001). Studies in Byzantine and Serbian Medieval Art. London: The Pindar Press. ISBN 9781899828340.

- Ivanović, Miloš (2019). "Serbian Hagiographies on the Warfare and Political Struggles of the Nemanjić Dynasty (from the Twelfth to Fourteenth Century)". Reform and Renewal in Medieval East and Central Europe: Politics, Law and Society. Cluj-Napoca: Romanian Academy, Center for Transylvanian Studies. pp. 103–129.

- ISBN 9781870732314.

- Jagić, Vatroslav (1883). Quattuor Evangeliorum versionis palaeoslovenicae Codex Marianus Glagoliticus, characteribus Cyrillicis transcriptum (PDF). Berlin: Weidmann.

- Janićijević, Jovan, ed. (1990). Serbian Culture Through Centuries: Selected List of Recommended Reading. Belgrade: Yugoslav Authors' Agency.

- Janićijević, Jovan, ed. (1998). The Cultural Treasury of Serbia. Belgrade: Idea, Vojnoizdavački zavod, Markt system. ISBN 9788675470397.

- Johnston, Douglas; Sampson, Cynthia, eds. (1995). Religion, the Missing Dimension of Statecraft. New York & Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195102802.

- Jovanović, Zdravko B. (2019). "Ecclesiology in Contemporary Serbian Theology: An Overview of some Important Perspectives". Die Serbische Orthodoxe Kirche in den Herausforderungen des 21. Jahrhunderts. Regensburg: Pustet. pp. 169–187. ISBN 9783791730578.

- Kalić, Jovanka (1995). "Rascia - The Nucleus of the Medieval Serbian State". The Serbian Question in the Balkans. Belgrade: Faculty of Geography. pp. 147–155.

- .

- Kašić, Dušan, ed. (1965). Serbian Orthodox Church: Its past and present. Vol. 1. Belgrade: Serbian Orthodox Church.

- Kašić, Dušan, ed. (1966). Serbian Orthodox Church: Its past and present. Vol. 2. Belgrade: Serbian Orthodox Church.

- Kašić, Dušan, ed. (1972). Serbian Orthodox Church: Its past and present. Vol. 3. Belgrade: Serbian Orthodox Church.

- Kašić, Dušan, ed. (1973). Serbian Orthodox Church: Its past and present. Vol. 4. Belgrade: Serbian Orthodox Church.

- Kašić, Dušan, ed. (1975). Serbian Orthodox Church: Its past and present. Vol. 5. Belgrade: Serbian Orthodox Church.

- Kašić, Dušan, ed. (1983). Serbian Orthodox Church: Its past and present. Vol. 6. Belgrade: Serbian Orthodox Church.

- Kia, Mehrdad (2011). Daily Life in the Ottoman Empire. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313064029.

- Kidd, Beresford James (1927). The Churches of Eastern Christendom: From A.D. 451 to the Present Time. London: Faith Press. ISBN 9780598821126.

- Kiminas, Demetrius (2009). The Ecumenical Patriarchate: A History of Its Metropolitanates with Annotated Hierarch Catalogs. Wildside Press LLC. ISBN 9781434458766.

- Komatina, Ivana (2016). Црква и држава у српским земљама од XI до XIII века [Church and State in the Serbian Lands from the XIth to the XIIIth Century]. Београд: Institute of History. ISBN 9788677431136.

- Komatina, Predrag (2014). "Settlement of the Slavs in Asia Minor During the Rule of Justinian II and the Bishopric των Γορδοσερβων" (PDF). Београдски историјски гласник: Belgrade Historical Review. 5: 33–42.

- Komatina, Predrag (2015). "The Church in Serbia at the Time of Cyrilo-Methodian Mission in Moravia". Cyril and Methodius: Byzantium and the World of the Slavs. Thessaloniki: Dimos. pp. 711–718.

- Krstić, Branislav (2003). Saving the Cultural Heritage of Serbia and Europe in Kosovo and Metohia. Belgrade: Coordination Center of the Federal Government and the Government of the Republic of Serbia for Kosovo and Metohia. ISBN 9788675560173.

- Kuburić, Zorica (2014). "Serbian Orthodox Church in the Context of History" (PDF). Religion and Tolerance: Journal of the Center for Empirical Researches of Religion. 12 (22): 387–402.

- Ljubinković, Radivoje (1975). The Church of the Apostles in the Patriarchate of Peć. Belgrade: Jugoslavija.

- Marjanović, Dragoljub (2018). "Emergence of the Serbian Church in Relation to Byzantium and Rome" (PDF). Niš and Byzantium. 16: 41–50.

- S2CID 96483243.

- Marković, Miodrag; Vojvodić, Dragan, eds. (2017). Serbian Artistic Heritage in Kosovo and Metohija: Identity, Significance, Vulnerability. Belgrade: Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts.

- ISBN 9789174022025.

- Mileusnić, Slobodan, ed. (1989). Serbian Orthodox Church: Its past and present. Vol. 7. Belgrade: Serbian Orthodox Church.

- Mileusnić, Slobodan (1997). Spiritual Genocide: A survey of destroyed, damaged and desecrated churches, monasteries and other church buildings during the war 1991–1995 (1997). Belgrade: Museum of the Serbian Orthodox Church.

- Mileusnić, Slobodan (1998). Medieval Monasteries of Serbia (4th ed.). Novi Sad: Prometej. ISBN 9788676393701.

- ISBN 9780884020219.

- Morrison, Kenneth; Čagorović, Nebojša (2014). "The Political Dynamics of Intra-Orthodox Conflict in Montenegro". Politicization of Religion, the Power of State, Nation, and Faith: The Case of Former Yugoslavia and its Successor States. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 151–170. ISBN 9781137477866.

- ISBN 9780351176449.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1956). History of the Byzantine State. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Paizi-Apostolopoulou, Machi (2012). "Appealing to the Authority of a Learned Patriarch: New Evidence on Gennadios Scholarios' Responses to the Questions of George Branković". The Historical Review. 9: 95–116.

- Pantelić, Bratislav (2002). The Architecture of Dečani and the Role of Archbishop Danilo II. Wiesbaden: Reichert. ISBN 9783895002397.

- Pavlović, Jovan, ed. (1992). Serbian Orthodox Church: Its past and present. Vol. 8. Belgrade: Serbian Orthodox Church.

- Pavlovich, Paul (1989). The History of the Serbian Orthodox Church. Serbian Heritage Books. ISBN 9780969133124.

- ISBN 9781850654773.

- Popović, Marko (1999). Tvrđava Ras [The Fortress of Ras] (in Serbian). Belgrade: Archaeological Institute. ISBN 9788680093147.

- Popović, Radomir V. (1996). Le Christianisme sur le sol de l'Illyricum oriental jusqu'à l'arrivée des Slaves. Thessaloniki: Institute for Balkan Studies. ISBN 9789607387103.

- Popović, Radomir V. (2013). Serbian Orthodox Church in History. Belgrade: Academy of Serbian Orthodox Church for Fine Arts and Conservation. ISBN 9788686805621.

- Popović, Svetlana (2002). "The Serbian Episcopal Sees in the Thirteenth Century". Старинар (51: 2001): 171–184.

- Prinzing, Günter (2012). "The autocephalous Byzantine ecclesiastical province of Bulgaria/Ohrid. How independent were its archbishops?". Bulgaria Mediaevalis. 3: 355–383. ISSN 1314-2941.

- Radić, Radmila (1998). "Serbian Orthodox Church and the War in Bosnia and Herzegovina". Religion and the War in Bosnia. Atlanta: Scholars Press. pp. 160–182. ISBN 9780788504280.

- Radić, Radmila (2007). "Serbian Christianity". The Blackwell Companion to Eastern Christianity. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 231–248. ISBN 9780470766392.

- Radić, Radmila (2015). "The Serbian Orthodox Church in the First World War". The Serbs and the First World War 1914-1918. Belgrade: Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts. pp. 263–285. ISBN 9788670256590.

- Radić, Radmila; Vukomanović, Milan (2014). "Religion and Democracy in Serbia since 1989: The Case of the Serbian Orthodox Church". Religion and Politics in Post-socialist Central and Southeastern Europe: Challenges since 1989. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 180–211. ISBN 9781137330727.

- Radojević, Mira; Mićić, Srđan B. (2015). "Serbian Orthodox Church cooperation and frictions with Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople and Bulgarian Exarchate during interwar period". Studia Academica šumenesia. 2: 126‒143.

- Roudometof, Victor (2001). Nationalism, Globalization, and Orthodoxy: The Social Origins of Ethnic Conflict in the Balkans. London: Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780313319495.

- ISBN 9780521313100.

- Šakota, Mirjana (2017). Ottoman Chronicles: Dečani Monastery Archives. Prizren: Diocese of Raška-Prizren.

- ISBN 9788675830153.

- Sedlar, Jean W. (1994). East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000-1500. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295800646.

- Slijepčević, Đoko M. (1958). The Macedonian Question: The Struggle for Southern Serbia. Chicago: The American Institute for Balkan Affairs.

- Sotirović, Vladislav B. (2011). "The Serbian Patriarchate of Peć in the Ottoman Empire: The First Phase (1557–94)". 25 (2): 143–169.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Soulis, George Christos (1984). The Serbs and Byzantium during the reign of Tsar Stephen Dušan (1331–1355) and his successors. Washington: Dumbarton Oaks Library and Collection. ISBN 9780884021377.

- Spasović, Stanimir (2004). "Serbian Orthodoxy in Canada". Diaspora Serbs: A Cultural Analysis. Edmonton: University of Alberta. pp. 95–168. ISBN 9780921490159.

- Špehar, Perica N. (2010). "By Their Fruit you will recognize them - Christianization of Serbia in Middle Ages". Tak więc po owocach poznacie ich. Poznań: Stowarzyszenie naukowe archeologów Polskich. pp. 203–220.

- Špehar, Perica N. (2015). "Remarks to Christianisation and Realms in the Central Balkans in the Light of Archaeological Finds (7th-11th c.)". Castellum, Civitas, Urbs: Centres and Elites in Early Medieval East-Central Europe. Budapest: Verlag Marie Leidorf. pp. 71–93.

- Stephenson, Paul (2000). Byzantium's Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900–1204. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521770170.

- Stojanović, Aleksandar (2017). "A Beleaguered Church: The Serbian Orthodox Church in the Independent State of Croatia (NDH) 1941-1945". Balcanica (48): 269–287. .

- Subotić, Gojko (1998). Art of Kosovo: The Sacred Land. New York: The Monacelli Press. ISBN 9781580930062.

- Subotin-Golubović, Tatjana (1999). "Reflection of the Cult of Saint Konstantine and Methodios in Medieval Serbian Culture". Thessaloniki - Magna Moravia: Proceedings of the International Conference. Thessaloniki: Hellenic Association for Slavic Studies. pp. 37–46. ISBN 9789608595934.

- Šuica, Marko (2011). "The Image of the Battle of Kosovo (1389) Today: a Historic Event, a Moral Pattern, or the Tool of Political Manipulation". The Uses of the Middle Ages in Modern European States: History, Nationhood and the Search for Origins. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 152–174. ISBN 9780230283107.

- Todić, Branislav (1999). Serbian Medieval Painting: The Age of King Milutin. Belgrade: Draganić. ISBN 9788644102717.

- Todić, Branislav; Čanak-Medić, Milka (2013). The Dečani Monastery. Belgrade: Museum in Priština. ISBN 9788651916536.

- Thomson, Francis J. (1993). "Archbishop Daniel II of Serbia: Hierarch, Hagiographer, Saint: With Some Comments on the Vitae regum et archiepiscoporum Serbiae and the Cults of Mediaeval Serbian Saints". Analecta Bollandiana. 111 (1–2): 103–134. .

- Todorović, Jelena (2006). An Orthodox Festival Book in the Habsburg Empire: Zaharija Orfelin's Festive Greeting to Mojsej Putnik (1757). Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 9780754656111.

- Tomić, Marko D. (2019). "The View on the Legal Position of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Bosnia and Herzegovina under the rule of the Austro-Hungarian Empire" (PDF). Зборник радова: Правни факултет у Новом Саду. 53 (4): 1445–1465.

- ISBN 9780804726306.

- Turlej, Stanisław (2016). Justiniana Prima: An Underestimated Aspect of Justinian's Church Policy. Krakow: Jagiellonian University Press. ISBN 9788323395560.

- Ubiparipović, Srboljub (2019). "Development of Liturgiology among the Orthodox Serbs and its Impact on Actual Liturgical Renewal in the Serbian Orthodox Church". Die Serbische Orthodoxe Kirche in den Herausforderungen des 21. Jahrhunderts. Regensburg: Pustet. pp. 258–267. ISBN 9783791730578.

- Vásáry, István (2005). Cumans and Tatars: Oriental Military in the Pre-Ottoman Balkans, 1185–1365. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139444088.

- Velikonja, Mitja (2003). Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 9781603447249.

- ISBN 9780521074599.

- Vuković, Sava (1998). History of the Serbian Orthodox Church in America and Canada 1891–1941. Kragujevac: Kalenić.

- Živković, Tibor; Bojanin, Stanoje; Petrović, Vladeta, eds. (2000). Selected Charters of Serbian Rulers (XII-XV Century): Relating to the Territory of Kosovo and Metohia. Athens: Center for Studies of Byzantine Civilisation.

- Živković, Tibor (2007). "The Golden Seal of Stroimir" (PDF). Historical Review. 55. Belgrade: The Institute for History: 23–29. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ISBN 9788675585732.

- Živković, Tibor (2010). "Constantine Porphyrogenitus' Source on the Earliest History of the Croats and Serbs". Radovi Zavoda Za Hrvatsku Povijest U Zagrebu. 42: 117–131.

- Živković, Tibor (2012). De conversione Croatorum et Serborum: A Lost Source. Belgrade: The Institute of History.

- Živković, Tibor (2013). "On the Baptism of the Serbs and Croats in the Time of Basil I (867–886)" (PDF). Studia Slavica et Balcanica Petropolitana (1): 33–53.

Further reading

- Srpsko Blago | Serbian Treasure site – photos, QTVR and movies of Serbian monasteries and Serbian Orthodox art

- Article on the Serbian Orthodox Church by Ronald Roberson on the CNEWA website

- Article on the medieval history of the Serbian Orthodox Church in the repository of the Institute for Byzantine Studies of the Austrian Academy of Sciences (in German)