Alamanno da Costa

Alamanno da Costa (active 1193–1224, died before 1229) was a Genoese admiral. He became the count of Syracuse in the Kingdom of Sicily, and led naval expeditions throughout the eastern Mediterranean. He was an important figure in Genoa's longstanding conflict with Pisa and in the origin of its conflict with Venice. The historian Ernst Kantorowicz called him a "famous prince of pirates".[1]

Early free-lance career

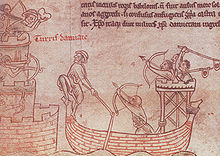

Alamanno came from Genoa's mercantile class, and the earliest record of him dates from 1193, when he joined an accomende, a commercial partnership, directed towards Sicily.[2] In 1204, Alamanno and his son Benvenuto, on their own initiative, set out aboard the Carroccia in search of the Pisan corsair Leopardo.[2] The Carroccia and Leopardo were both classed as navi—broad-beamed, lateen-rigged ships.[3] The former had on board 500 armed men, and the latter probably half as many. The inventory taken after Alamanno successfully captured the Leopardo and integrated her into his force lists 280 suits of armour among the booty. Presumably this represents the number of marines she carried.[4]

In 1162 the

Count of Syracuse

Alamanno took the pompous and probably self-appointed title "

Alamanno was in a close alliance with Enrico Pescatore, to whom he lent the use of the Leopardo.

Activities in the East

In 1216, Alamanno assisted Enrico in an attempt to conquer

In 1220 Frederick II began asserting royal rights in Syracuse, attempting to throw out the Genoese, and proclaiming the city "most faithful" (fidelissima).

Notes

- ^ a b c d e Cheyette 1970, p. 46.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Oreste 1960.

- ^ Dotson 2006, p. 65. The Italian term nave derives from the Latin navis, which also gives rise to the French nef. It was a general term meaning "ship", but modern historians use it in a more technical sense.

- Ogerio Pane.

- ^ a b Pryor 1999, p. 424. Enrico first began trying to conquer Crete in 1205, when he embarked on a campaign in the eastern Mediterranean, in which he first utilised the Leopardo.

- ^ a b c d e f Abulafia 2004, pp. 1064–65.

- ^ Dotson 2006, p. 68. These Pisans were described as pirati by Ogerio, but the word was a mere pejorative, although the Pisans did prey on Genoese shipping.

- ^ Abulafia 1988, p. 103.

- ^ Dotson 2006, p. 67.

- ^ a b c Dotson 2006, p. 68–69.

- ^ Abulafia 1988, p. 142.

Sources

- Abulafia, David (1988). Frederick II: A Medieval Emperor. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Abulafia, David (2004). "Syracuse". In Christopher Kleinheinz (ed.). Medieval Italy: An Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. New York: Taylor & Francis. pp. 1064–65.

- Cheyette, Fredric L. (1970). "The Sovereign and the Pirates, 1332". Speculum. 45 (1): 40–68. S2CID 159666608.

- Dotson, John E. (2006). "Ship Types and Fleet Composition at Genoa and Venice in the Early Thirteenth Century". In John H. Pryor (ed.). Logistics of Warfare in the Age of the Crusades. Aldershot: Ashgate. pp. 63–76.

- Oreste, Giuseppe (1960). "Alamanno da Costa". In Alberto Maria Ghisalberti (ed.). Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Vol. 1. Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia italiana. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- Pryor, John H. (1999). "The Maritime Republics". In David Abulafia (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History. Vol. V. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 419–46.