Alamosaurus

| Alamosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Restored skeletons of Alamosaurus and Tyrannosaurus at Perot Museum | |

| |

| Life reconstruction of Alamosaurus sanjuanensis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Clade: | †Macronaria |

| Clade: | †Titanosauria |

| Family: | †Saltasauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Opisthocoelicaudiinae |

| Genus: | †Alamosaurus Gilmore, 1922 |

| Type species | |

| †Alamosaurus sanjuanensis Gilmore, 1922

| |

Alamosaurus (

Description

Alamosaurus was a gigantic

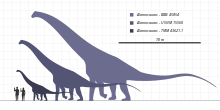

In 2019, Gregory S. Paul estimated SMP VP−1625 at 27 tonnes (30 short tons) and he also mentioned a large partial anterior caudal vertebra that suggests an Alamosaurus specimen that is 15 percent dimensionally larger and with similar mass to his Dreadnoughtus estimation of 31 tonnes (34 short tons).[9] In 2020, Molina-Perez and Larramendi estimated the size of the largest individual at 26 meters (85.3 ft) and 38 tonnes (42 short tons).[10] In 2023, the largest individual was stated to be around 30 meters (98 ft) and 72.5 tonnes (80 short tons).[11]

Though no skull has ever been found, rod-shaped teeth have been found with Alamosaurus skeletons and probably belonged to this dinosaur.

History

Alamosaurus remains have been discovered throughout the

In 1946, Gilmore posthumously described a more complete specimen, USNM 15660, found on June 15, 1937, on the North Horn Mountain of Utah by George B. Pearce. It consists of a complete tail, a complete right forelimb (except for the fingers, which later research showed do not ossify with Titanosauridae), and both ischia.[18] Since then, hundreds of other bits and pieces from Texas, New Mexico, and Utah have been referred to Alamosaurus, often without much description. Despite being fragmentary, until the second half of the twentieth century they, represented much of the globally known titanosaurid material. The most completely known specimen, TMM 43621–1, is a juvenile skeleton from Texas which allowed educated estimates of length and mass.[3]

Some blocks catalogued under the same accession number as the relatively complete and well-known Alamosaurus specimen USNM 15660 and found in very close proximity to it based on bone impressions were first investigated by Michael Brett-Surman in 2009. In 2015, he reported that the blocks contained osteoderms, the first confirmation of their existence on Alamosaurus.[4]

The restored Alamosaurus skeletal mount at the Perot Museum [19][circular reference] (pictured right) was discovered when student Dana Biasatti, a member of an excavation team at a nearby site, went on a hike to search for more dinosaur bones in the area.

Classification

In 1922, Gilmore was uncertain about the precise affinities of Alamosaurus and did not determine it any further than a general

Alamosaurus was, in any case, an advanced and derived member of the group

Phylogeny

Alamosaurus in a cladogram after Navarro et al., 2022:[25]

| Saltasauridae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Age

Alamosaurus fossils are most notably found in the Naashoibito member of the

Biogeography

Alamosaurus is the only known sauropod to have lived in North America after the sauropod hiatus, a nearly 30-million-year interval for which no definite sauropod fossils are known from the continent. The earliest fossils of Alamosaurus date to the Maastrichtian age, around 70 million years ago, and it rapidly became the dominant large herbivore of southern Laramidia.[28]

The origins of Alamosaurus are highly controversial, with three hypotheses that have been proposed. The first of these, which has been termed the "austral immigrant" scenario,[29] proposes that Alamosaurus is descended from South American titanosaurs. Alamosaurus is closely related to South American titanosaurs, such as Pellegrinisaurus.[30][31] Alamosaurus appears in North America at the same time that hadrosaurs closely related to North American species first appear in South America, suggesting that the Alamosaurus lineage crossed into North America on the same routes as hadrosaurs crossed into South America.[32] The austral immigrant hypothesis has been challenged on the grounds that the routes connecting North and South America during the Maastrichtian may have consisted of separate islands, which would have presented challenges to the dispersal of titanosaurs.[28][33] A second scenario, termed the "inland herbivore" scenario,[29] suggests that titanosaurs were present in North America throughout the Late Cretaceous and that their apparent absence reflects the relative rarity of fossil sites preserving the upland environments that titanosaurs favored, rather than their true absence from the continent.[28] However, there is no evidence for sauropods in North America between the mid-Cenomanian and the early Maastrichtian, even in strata that preserve more upland environments, and the sauropods that lived in North America before the hiatus are basal titanosauriforms, such as Sonorasaurus and Sauroposeidon, not lithostrotian titanosaurs.[32][34] A third option is that, as in the austral immigrant scenario, Alamosaurus is not native to North America, but originated in Asia instead of South America.[33] Alamosaurus is commonly considered to be closely related to the Asian titanosaur Opisthocoelicaudia, but this is based on analyses that did not take Alamosaurus's South American relative Pellegrinisaurus into account.[30] Though many dinosaurs crossed between Asia and North America across the Bering land bridge, sauropods were poorly adapted for high-latitude environments and Beringia would have been an inhospitable environment for titanosaurs.[35] Furthermore, in order to reach southern Laramidia from Asia, Alamosaurus would have had to cross through Northern Laramidia, which contains no known sauropod fossils of comparable age to Alamosaurus, despite containing the best-studied dinosaur faunas on the continent.[23] Overall, a South American origin has been favored by several studies[31][23][30][35] and was regarded as "the only viable origin" for Alamosaurus by Chiarenza et al.[35]

Paleoecology

Skeletal elements of Alamosaurus are among the most common Late Cretaceous dinosaur fossils found in the United States Southwest and are now used to define the fauna of that time and place, known as the "Alamosaurus fauna". In the south of Late Cretaceous North America, the transition from the Edmontonian to the Lancian faunal stages is even more dramatic than it was in the north. Thomas M. Lehman describes it as "the abrupt reemergence of a fauna with a superficially 'Jurassic' aspect. These faunas are dominated by Alamosaurus and feature abundant Quetzalcoatlus in Texas. The Alamosaurus-Quetzalcoatlus association probably represent semi-arid inland plains.[28]

Contemporaries of Alamosaurus in the American southwest include the

]References

- ^ "Alamosaurus". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021.

- ^ S2CID 53126360.

- ^ S2CID 232345559.

- ^ S2CID 86797277.

- (PDF).

- ^ Holtz Jr., Thomas R. (2014). "Supplementary Information to Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages".

- ^ "Assessing Alamosaurus". Skeletal Drawing.

- ^ "The biggest of the big". Skeletal Drawing.

- S2CID 210840060.

- Bibcode:2020dffs.book.....M.

- ^ "Newest fossil display at NM Museum of Natural History & Science has deep ties to the Land of Enchantment". New Mexico Department of Cultural Affairs. Retrieved April 18, 2024.

- ^ a b Weishampel, D.B. et al.. (2004). "Dinosaur Distribution (Late Cretaceous, North America)". In Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., Oslmolska, H. (eds.). "The Dinosauria (Second ed.)". University of California Press.

- ^ a b c d e Tidwell, V., Carpenter, K. & Meyer, S. 2001. New Titanosauriform (Sauropoda) from the Poison Strip Member of the Cedar Mountain Formation (Lower Cretaceous), Utah. In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. D. H. Tanke & K. Carpenter (eds.). Indiana University Press, Eds. D.H. Tanke & K. Carpenter. Indiana University Press. 139–165.

- ^ [1], John Bernard Reeside (1889-1958) was a geologist specializing in the study of the Mesozoic stratigraphy and paleontology of the western United States. While receiving his education at The Johns Hopkins University (A.B., 1911; Ph.D., 1915), he joined the United States Geological Survey (USGS) as a part-time assistant... [and] remained with the USGS for his entire professional career... From 1932 to 1949, Reeside was Chief of the Paleontology and Stratigraphy Branch.

- ^ a b c Gilmore, C.W. (1922). "A new sauropod dinosaur from the Ojo Alamo Formation of New Mexico" (PDF). Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections. 72 (14): 1–9.

- ISBN 0-8137-2238-1.

- ^ Anthony D. Fredericks, 2012, Desert Dinosaurs: Discovering Prehistoric Sites in the American Southwest, The Countryman Press, p. 102-103

- ^ Gilmore, C.W. 1946. Reptilian fauna of the North Horn Formation of central Utah. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper. 210-C:29–51.

- ^ Perot Museum of Nature and Science

- ^ v. Huene, F. (1927). "Sichtung der Grundlagen der jetzigen Kenntnis der Sauropoden". Eclogae Geologicae Helveticae. 20: 444–470.

- .

- ^ Upchurch, P., Barrett, P.M. & Dodson, P. 2004. Sauropoda. In: Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P., & Osmolska, H. (Eds.) The Dinosauria (2nd Edition). Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 259–322.

- ^ .

- ^ "Blogs". PLOS. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- S2CID 251875979.

- ^ Sullivan, R.M., and Lucas, S.G. 2006. "The Kirtlandian land-vertebrate "age" – faunal composition, temporal position and biostratigraphic correlation in the nonmarine Upper Cretaceous of western North America[permanent dead link]." New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science, Bulletin 35:7–29.

- ^ S2CID 130280606.

- ^ ISBN 0-253-33907-3.

- ^ ISBN 0-8137-2238-1.

- ^ ISSN 0195-6671.

- ^ PMID 27048465.

- ^ ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ ISSN 0031-0182.

- S2CID 128486488.

- ^ S2CID 245273901.