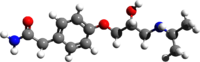

Atenolol

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Tenormin, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a684031 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

β1 receptor antagonist | |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Elimination half-life | 6–7 hours[2] |

| Duration of action | >24 hours[2] |

| Excretion | Urine (>85% IV, 50% oral)[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| Chirality | Racemic mixture |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Atenolol is a

Common

Atenolol was patented in 1969 and approved for medical use in 1975.

Medical uses

Atenolol is used for a number of conditions including

The role for β-blockers in general in hypertension was downgraded in June 2006 in the United Kingdom, and later in the United States, as they are less appropriate than other agents such as

Side effects

Hypertension treated with a β-blocker such as atenolol, alone or in conjunction with a thiazide diuretic, is associated with a higher incidence of new onset type 2 diabetes mellitus compared to those treated with an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker. [17][18]

β-blockers, of which atenolol is mainly studied, provides weaker protection against stroke and mortality in patients over 60 years old compared to other antihypertensive medications.[19][20][21][14] Diuretics may be associated with better cardiovascular and cerebrovascular outcomes than β-blockers in the elderly.[22]

Overdose

Symptoms of

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Atenolol is a

Beta-blocking effects of atenolol include reduction in

Pharmacokinetics

The

The

Atenolol undergoes little to no metabolism by the liver.[2] This is in contrast to other beta blockers like propranolol and metoprolol, but is similar to nadolol.[2] Instead of hepatic metabolism, atenolol is eliminated mainly via renal excretion.[2] Atenolol is excreted 50% in urine with oral administration and more than 85% in urine with intravenous administration.[2]

The

Society and culture

Atenolol has been given as an example of how slow healthcare providers are to change their prescribing practices in the face of

References

- FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab "DailyMed - TENORMIN- atenolol tablet". DailyMed. 30 June 2021. Archived from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Atenolol Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. AHFS. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- PMID 24672712.

- PMID 25821584.

- ^ ISBN 9780857113382.

- ^ "Atenolol use while Breastfeeding". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 23 December 2018. Retrieved 23 December 2018.

- ISBN 9783527607495.

- hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2021". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Atenolol - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- from the original on 10 October 2022. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- ^ "Atenolol". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- ^ PMID 28107561.

Further research should be of high quality and should explore whether there are differences between different subtypes of beta-blockers or whether beta-blockers have differential effects on younger and older people [...] Beta-blockers were not as good at preventing the number of deaths, strokes, and heart attacks as other classes of medicines such as diuretics, calcium-channel blockers, and renin-angiotensin system inhibitors. Most of these findings come from one type of beta-blocker called atenolol. However, beta-blockers are a diverse group of medicines with different properties, and we need more well-conducted research in this area." (p. 2-3)

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Archived from the originalon 11 May 2008. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- PMID 17433471.

- S2CID 23613019.

- S2CID 37044384.

- S2CID 34364430.

- PMID 16754904.

- PMID 24750981.

- PMID 9634263.

- PMID 7605000.

- ^ Baselt R (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, Calif.: Biomedical Publications. pp. 116–117.

- ^ PMID 33572109.

- ^ a b c d Epstein D (22 July 2017). "When Evidence Says No, But Doctors Say Yes". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 9 May 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- PMID 30384549.