Battle of Gembloux (1578)

| Battle of Gembloux | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eighty Years' War | |||||||

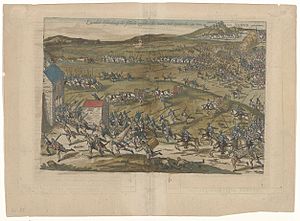

Engraving of the Battle of Gembloux by Frans Hogenberg | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

States-General |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Marquis d’Havré Henry Balfour |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 20,000 men |

17,000–20,000[2] (Only engaged 1,200 cavalry in the first phase of the battle)[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

6,000 killed [2] Hundreds of prisoners[2] |

20 dead or wounded (12 dead in action)[3] | ||||||

The Battle of Gembloux took place at

Prelude

After the

However, in the summer of 1577, Don John (brandishing the motto In hoc signo vici Turcos, in hoc vincam haereticos—"in this sign I conquered the Turks, in this I shall conquer the heretics")

The

Battle of Gembloux

In the last days of January 1578, the

When De Goignies learned that the Spanish army was approaching Namur, he decided to withdraw to Gembloux.[16]

Parma's action

At dawn on 31 January, the Spanish army marched towards the rebel army, with the cavalry under Ottavio Gonzaga in the vanguard, followed by musketeers and infantry commanded by Don Cristóbal de Mondragón, and then the bulk of the army led by Don John of Austria and Don Alexander Farnese.[11][17] The rearguard was commanded by the Count of Mansfeld.[11]

The Spanish

Destruction of the states-general's army

The Netherlandish army tried to regroup, but a cannon and its ammunition blew up, causing many deaths and renewed panic. Meanwhile, part of the rebel troops, mostly Dutch and Scots led by Colonel

Aftermath

The defeat at Gembloux led to military pressure on Brussels, causing the States General of the Netherlands to leave and move to Antwerp.[22] Prince William of Orange, the leader of the revolt, also left, along with its nominal governor, Matthias of Austria (the future Holy Roman Emperor), who had accepted the position of governor-general by the states-general, although he was not recognized by his uncle, Philip II of Spain.[11] The victory of John also meant the end of the Union of Brussels, and hastened the disintegration of the unity of the rebel provinces.[6][failed verification]

John died nine months after the battle (probably from typhus), on 1 October 1578, and was succeeded by Farnese as governor-general (last desire of John that Philip II confirmed), who at the head of the Spanish army reconquered large parts of the Low Countries in the following years.[4]

On 6 January 1579 the provinces loyal to the

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c Tony Jaques p. 368

- ^ a b c d e f Colley Grattan p. 157

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Colley Grattan. Holland p. 113

- ^ a b Morris p. 268

- ^ It was commanded by Antoine de Goignies, a gentleman of Hainault, and an old soldier of the school of Charles V. Holland. Grattan p. 113

- ^ a b c Tracy pp. 140–141

- ^ Morris p. 274

- ISBN 978-0-582-78464-2.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - ^ Tracy pp. 135–136

- ^ Tracy p. 137

- ^ a b c d e f g Vicent p. 228

- ^ a b Vicent pp. 227–228

- ^ a b Grattan p. 157

- ^ Marek y Villarino de Brugge 2020a, v. I p. 211.

- ^ Philip II of Spain. p. 224

- ^ a b c Jaques p. 368

- ^ Marek y Villarino de Brugge 2020a, v. I pp. 211-213.

- ^ Marek y Villarino de Brugge 2020a, v. I p. 213.

- ^ Marek y Villarino de Brugge 2020a, v. I pp. 213-214.

- ^ Marek y Villarino de Brugge 2020a, v. I pp. 214-215.

- ^ Hernán/Maffi p. 24

- ^ Tracy p. 141

- ^ a b Israel p. 191

- ^ Marek y Villarino de Brugge 2020b, v. II p. 124.

References

- Abernethy, Jack (2020). "Balfour of Mackerston, Henry [SSNE 5011]." on the Scotland, Scandinavia, and Northern Europe Database. https://www.st-andrews.ac.uk/history/ssne/item.php?id=5011

- Cadenas y Vicent, Vicente. Carlos V: Miscelánea de artículos publicados en la revista "Hidalguía". Madrid 2001. ISBN 84-89851-34-4(in Spanish)

- Colley Grattan, Thomas. History of the Netherlands. London. 1830.

- Colley Grattan, Thomas. Holland. Published by The Echo Library 2007. ISBN 978-1-40686-248-5

- Elliott, John Huxtable (2000). Europe Divided, 1559–1598. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-21780-0

- García Hernán, Enrique./Maffi, Davide. Guerra y Sociedad en la Monarquía Hispánica. Volume 1. Published 2007. ISBN 978-84-8483-224-9

- Israel, Jonathan (1995). The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477–1806. Clarendon Press. Oxford. ISBN 0-19-873072-1

- Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: A Guide to 8,500 Battles from Antiquity Through the Twenty-first Century. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33537-2

- Marek y Villarino de Brugge, André (2020a). Alessandro Farnese: Prince of Parma: Governor-General of the Netherlands (1545–1592): v. I. Los Angeles: MJV Enterprises ltd. inc. ISBN 979-8687255998.

- Marek y Villarino de Brugge, André (2020b). Alessandro Farnese: Prince of Parma: Governor-General of the Netherlands (1545-1592): v. II. Los Angeles: MJV Enterprises, ltd., inc. ISBN 979-8687563130.

- T.A. Morris. Europe and England in the Sixteenth Century. First published 1998. USA. ISBN 0-203-20579-0

- Parker, Geoffrey. The Army of Flanders and the Spanish Road, 1567–1659. Cambridge. 1972. ISBN 0-521-83600-X

- Tracy, J.D. (2008). The Founding of the Dutch Republic: War, Finance, and Politics in Holland 1572–1588. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-920911-8

External links

- Biography of Don Cristóbal de Mondragón (in Spanish)