Brooklyn Museum

Entrance facade of Brooklyn Museum | |

| |

Former name | Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, Brooklyn Museum of Art |

|---|---|

| Established | August 1823 (as Brooklyn Apprentices' Library) |

| Location | 200 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, New York |

| Coordinates | 40°40′16.7″N 73°57′49.5″W / 40.671306°N 73.963750°W |

| Type | Art museum |

| Collection size | 500,000 objects |

| Public transit access | Subway: |

| Website | www |

Brooklyn Museum | |

New York City Landmark No. 0155

| |

| Location | 200 Eastern Parkway Brooklyn, NY 11238 |

| Coordinates | 40°40′16.7″N 73°57′49.5″W / 40.671306°N 73.963750°W |

| Built | 1895 |

| Architect | McKim, Mead & White; French, Daniel Chester |

| Architectural style | Beaux-Arts |

| NRHP reference No. | 77000944[1] |

| NYCL No. | 0155 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | August 22, 1977 |

| Designated NYCL | March 15, 1966 |

The Brooklyn Museum is an

The Brooklyn Museum was founded in 1823 as the Brooklyn Apprentices' Library and merged with the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences in 1843. The museum was conceived as an institution focused on a broad public.[3] The Brooklyn Museum's current building dates to 1897 and has been expanded several times since then. The museum initially struggled to maintain its building and collection, but it was revitalized in the late 20th century following major renovations.

Significant areas of the collection include antiquities, specifically their collection of

History

The Brooklyn Museum's origins date to August 1823,[5][6] when Augustus Graham founded the Brooklyn Apprentices' Library in Brooklyn Heights.[7][8] The library was formally incorporated November 24, 1824,[6] and the cornerstone of the library's first building was laid in 1825 on Henry and Cranberry Street.[9] The Library moved into the Brooklyn Lyceum building on Washington Street in 1841.[10] The two institutions merged into the Brooklyn Institute in 1843; the institute offered exhibitions of painting and sculpture and lectures on diverse subjects.[9][10] The Washington Street building was destroyed in a fire in 1891.[11]

Development and opening

In February 1889, several prominent Brooklyn citizens announced that they would begin fundraising for a new museum for the Brooklyn Institute.[12][13] The museum's proponents quickly identified a site just east of Prospect Park, on the south side of Eastern Parkway.[14] The next year, under director Franklin Hooper, Institute leaders reorganized as the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences and began planning the Brooklyn Museum.[15] Brooklyn officials hosted an architectural design competition for the building, eventually awarding the contract to McKim, Mead & White.[8] The competition was characterized in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle as "one of the most important in the history of architecture", as the museum was to contain numerous divisions.[8] The museum remained a subdivision of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, along with the Brooklyn Academy of Music, the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, and the Brooklyn Children's Museum, until these organizations all became independent in the 1970s.[10]

Brooklyn mayor Charles A. Schieren agreed in January 1895 to issue $300,000 per year in bonds for the Brooklyn Institute museum's construction.[16] Initially, only a single wing and pavilion on the western portion of the museum's site, measuring 210 by 50 feet (64 by 15 m) across, was to be built.[17] Engineers began surveying the site that May[18][19] and found that the bedrock under the site was several hundred feet deep, making it impossible to build the foundations on solid rock.[20] Nonetheless, the engineers had determined that the gravel fill under the site was strong enough to support a building.[18] Construction on the Brooklyn Museum of Arts and Sciences' west wing officially began on September 14, 1895.[21][22] A groundbreaking ceremony for the museum was hosted on December 14 of the same year.[23][24] Two of the museum's three stories had been completed by April 1896.[25]

The Brooklyn Institute museum's building was completed in March 1897 after a sidewalk was built between the museum's entrance and Eastern Parkway.[26] The museum's first exhibit was a collection of almost 600 paintings, which had opened to the public on June 1, 1897, several months before the formal opening of the museum.[27] The Brooklyn Institute's museum formally opened on October 2, 1897, and was one of the last major structures built in the city of Brooklyn before the formation of the City of Greater New York in 1898.[28][29]

20th century

1900s and 1910s

The Brooklyn Institute approved the construction of the central entrance pavilion in May 1899,[30] and Hooper requested $600,000 for this addition the next month.[31][32] The four-story structure was to measure 140 by 122 feet (43 by 37 m).[33][34] The central pavilion was to include a 1,250-seat lecture hall in the basement (actually at ground level),[30][35] as well as a hall of sculpture on the first floor, which would serve as the museum's main lobby.[30][33] The second story was to contain natural-history exhibits, while the third story was to include paintings.[33] The New York State Legislature needed to authorize $300,000 in bonds for the pavilion, but they had not done so by the end of 1899.[36] Work on the central wing started in June 1900.[34][37] The museum's central section was nearly completed by January 1903,[38] but work proceeded slowly due to labor disputes.[35]

New York City mayor Seth Low signed a bill in August 1902, approving $150,000 for the construction of the Brooklyn Institute's eastern wing and pavilion.[39] The eastern wing cost $344,000 to construct,[40] and it officially opened on December 14, 1907.[41][42] With the opening of the eastern wing, the museum building had reached one-eighth of its total planned size.[43] Although the museum's collections continued to grow, the New York City government was only willing to give the museum as little funding as necessary for essential maintenance.[44] Several of the institute's donors proposed in 1905 to give $25,000 for the upkeep of an "astronomical observatory" at the Brooklyn Museum.[45][46] City officials endorsed the creation of the observatory in 1907.[47]

The Brooklyn Institute awarded a construction contract for wings F and G, extending south of the central pavilion, to Benedetto & Egan in May 1911.[48] Extending 120 feet (37 m) south and measuring 200 feet (61 m) wide, this addition was to contain a central court with a glass roof.[48][49] That July, McKim, Mead & White filed plans for wings F and G.[50] The Brooklyn Institute converted the last remaining storage rooms in the eastern wing into galleries in October 1911.[51][52] The next month, a temporary access road was built from Flatbush Avenue to the rear of the building.[53] Wills & Martin, one of the firms that had been hired to erect the new wings, declared bankruptcy in November 1913.[54] Work stopped completely in November 1914,[55] and the incomplete structures started to deteriorate.[56] Because of the lack of space in the building, the lobby and auditorium were being used to exhibit artwork. The Brooklyn Institute had been forced to decline some donations of artwork, as the works could not be displayed, while other works of art had to be placed in storage.[56]

1920s to 1940s

By 1920, the New York City Subway's Institute Park station had opened outside the Brooklyn Museum, greatly improving access to the once-isolated museum from Manhattan and the other boroughs.[57] In April 1922, governor Nathan L. Miller signed legislation authorizing the New York City government to issue bonds to fund wings F and G of the Brooklyn Museum.[58] The New York City Board of Estimate refused to approve the Brooklyn Institute trustees' request for $875,000,[59] and mayor John Francis Hylan also blocked the funding.[60] Hylan changed his mind after visiting the museum, and the Board of Estimate appropriated $1.05 million for the new wings.[61] McKim, Mead & White drew up new plans for wings F and G; by that September, New York City Department of Parks and Recreation (NYC Parks) was about to award contracts for the wings.[62][63] A picture gallery opened at the museum in November 1925.[64][65] The next month, museum officials dedicated the Ethnological Gallery, which was nicknamed "Rainbow House";[66][67] the gallery was designed by curator Stewart Culin.[68] A Japanese art gallery opened at the museum in April 1927,[69] and the museum's Swiss Gothic, German, and Venetian galleries opened that May.[70][71]

Construction of the Brooklyn Museum stalled in 1928 after years of attempts to complete it. At the time, only 28 of the 80 proposed statues atop the building's facade had been installed, and the main north–south corridor was not complete.[8] Nineteen American period rooms opened at the museum at the end of 1929.[72] In May 1934, NYC Parks approved plans for the removal of the main entrance steps, which would be replaced by five large ground level doors.[73] The project also included the construction of two galleries next to the lobby.[74] This work was carried out by Public Works Administration laborers.[75] A gallery dedicated to living artists' work opened in February 1935,[76] and a Persian art gallery opened two months later.[77][78] The remodeled entrance was officially dedicated on October 5, 1935.[74][79] That December, the museum's medieval art gallery opened.[80][81] A gallery for industrial art was proposed behind the western wing the same year but was not built.[82] By early 1938, museum officials sought more than $300,000 for repairs to the museum building,[83][84] and then-director Philip Newell Youtz said that parts of the building were crumbling.[84]

The Brooklyn Museum Art School, formerly a part of the Brooklyn Academy of Music, was moved to the Brooklyn Museum in 1941.[85] An art distribution center sponsored by the Works Progress Administration opened on the museum's sixth floor the same year.[86][87] The department store chain Abraham & Straus donated $50,000 in 1948 for the establishment of a "laboratory of industrial design" at the Brooklyn Museum.[88][89] By the following year, Brooklyn Institute officials sought to expand the museum as part of a "vast cultural program".[90][91] The plans involved an annex with a 2,500-seat auditorium behind the west wing, which was planned to cost $500,000, as well as a general renovation of existing facilities, which was to cost $1.5 million.[91] A new 400-seat lecture hall opened at the museum that September, within space formerly occupied by two Egyptian galleries.[92] To attract visitors, the museum expanded its educational programs greatly in the late 1940s.[93]

1950s and 1960s

Brooklyn Institute officials announced plans in 1951 to repair the Brooklyn Museum as part of the institute's long-term plan to convert the museum into a cultural center.[94] The museum's Egyptian galleries began undergoing renovations the same year.[95][96] The renovation of the Egyptian galleries, the first phase of the museum's $3.5 million overhaul, was finished in November 1953.[97][98] Brown, Lawford & Forbes designed a rear annex for the museum in 1955.[8] The museum's furniture, sculpture, and watercolor galleries reopened in 1957 following the second stage of the renovation.[99][100] The rear annex contained a new stairway,[100] which led to new galleries on the fourth through sixth stories of the center section.[101] By the late 1950s, the museum was running low on funds, with director Edgar C. Schenck blaming the museum's fiscal woes on Manhattan residents' unwillingness to cross the East River to visit Brooklyn.[102] Due to a shortage of security guards, the museum was forced to close some galleries part-time.[103]

Another Egyptian gallery opened in April 1959,[104][105] and a "pattern library" for teaching opened that July.[106][107] A continued shortage of security guards forced the Brooklyn Museum to close two days a week at the beginning of 1961;[108] the museum went back to seven-day operations in June 1961 after the city provided money for additional guards.[109] To attract visitors, the museum began providing a larger variety of programs and adding interactive exhibits and programming.[110] The Brooklyn Museum announced in 1964 that it would build a special-exhibit gallery on the first floor and an open study/storage gallery on the fifth floor.[111][112] The Hall of the Americas opened on the museum's first floor the following May.[113][114] A sculpture garden, consisting of architectural details salvaged from demolished buildings across New York City, opened at the museum in April 1966.[115][116] The Brooklyn Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art began coordinating joint programs and exhibitions in 1967.[117]

By the late 1960s, the museum was again facing a funding shortage; several galleries had been temporarily closed due to a lack of money, and its director Thomas Buechner was considering closing the museum two days a week.[118] Brooklyn Museum officials also wanted to hire additional security guards to deter crime.[119] The Brooklyn Museum's Community Gallery, exhibiting black New Yorkers' art, opened in October 1968[120][121] following advocacy from Federated Institutes of Cultural Enrichment (FICE), a coalition of Brooklyn-based arts organizations.[122] The gallery occupied a narrow corridor at ground level.[123] Henri Ghent, the director of the Community Gallery, estimated in 1970 that "perhaps 100,000" additional patrons had been attracted to the museum after the gallery opened,[123][124] including black patrons who had never before visited a museum.[124]

1970s and early 1980s

The Brooklyn Museum continued to experience financial shortfalls in the early 1970s.[124] Due to a shortage of security guards, in mid-1971, museum officials announced that they would close the museum two days per week, allowing all galleries to remain open even with limited security.[125][126] The museum also reopened its 23 period rooms that October after a yearlong closure,[127] and they also opened a new period room, themed to a private study.[127][128] Officials planned to move the Community Gallery to a dedicated space adjoining the museum;[129] the gallery was popular among guests but did not have enough funding from the museum itself.[130] By late 1973, twenty percent of the museum's staff professionals had resigned amid a dispute involving director Duncan F. Cameron's firing of another employee,[131] eventually prompting Cameron's own resignation that year.[132][133] Further staff disputes complicated the search for a replacement director,[134] and many employees went on strike in 1974 because they wanted to form a labor union.[135][136]

By the mid-1970s, there were plans to split the

Two of the museum's period rooms reopened in 1980 following a renovation.[148] By then, director Michael Botwinick was considering several measures to reduce the museum's budgetary shortfalls, including halving the number of art classes, closing the museum during the workweek, and hosting fewer exhibits per year.[149] At the time, the museum received 31 percent of its funds from the city, a higher percentage than other New York City museums;[149] the city still owned the building itself.[150] After Robert Buck became director in 1983, he began hosting additional art classes, attracting members, and raising money for the museum,[151] which struggled to compete with more famous institutions in Manhattan.[152] In 1984, the museum completed the renovations of its last period rooms[143][153] and opened a gallery for "early-19th-century decorative arts".[153] The unprofitable Brooklyn Museum Art School was closed the same year,[85] and the museum obtained $14 million in city funding to upgrade the climate-control systems.[151] The museum resumed Monday operations in late 1984 after receiving additional city funding,[154] and it started running TV advertisements in 1985.[155]

Mid-1980s and 1990s

The Brooklyn Museum announced a master plan in March 1986.[156][157] The plan involved doubling the amount of exhibition space in the building from 450,000 to 830,000 square feet (42,000 to 77,000 m2).[156] At the time, the museum could only exhibit about five percent of its collection simultaneously,[156] as its building was one-sixth as large as originally planned.[158] The museum was to expand its storage, classroom, and conservation facilities and add an auditorium.[156] Buck met with the heads of all of the museum's departments to determine how much exhibit and storage space they needed.[158] The museum also planned a new entrance from the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, which had twice as many annual visitors;[157][158] the Botanic Garden entrance had been planned by McKim, Mead & White but never executed.[156] The project was expected to cost $50 million to $100 million,[158][157] which was to be funded by the city's capital budget.[159]

Museum officials held an

The auditorium opened in 1991; at the time, there had not been an auditorium at the museum for over half a century.[172] About 33,000 square feet (3,100 m2) in the museum's west wing reopened as gallery space in November 1993.[173][174] The renovation retained the original layout of the west-wing spaces.[175] The New York Times described Isozaki and Polshek's renovation as aiming for "clean, serene spaces"; the rooms had rooms with maple floors, white walls, horizontal lighting strips, and granite baseboards.[176] The west wing was renamed for investor Morris A. Schapiro and his brother, art historian Meyer Schapiro, in early 1994 after Morris Schapiro donated $5 million.[177][178]

The Brooklyn Museum changed its name to Brooklyn Museum of Art in 1997.[179] According to acting director Linda S. Ferber, the renaming was necessary because "there was more confusion about the museum's identity than we supposed"; for instance, many visitors still believed the museum had natural-history exhibits, which had not been the case since 1934.[180]

21st century

Brooklyn Museum officials hired architect James Polshek in 2000 to design a new glass-clad entrance for the building at a cost of $55 million.[181][182] Polshek described the front entrance as a "wasteland" at the time, and he said he wanted to build "Brooklyn's new front stoop".[181] The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission approved Polshek's design, despite opposition from preservationists.[183] The renovation cost $63 million[184][185] and also added air conditioning throughout the museum building.[186] The Henry Luce Foundation gave the museum a $10 million grant in 2001, which funded the construction of the Luce Center for American Art on the fifth floor.[187] The museum's renovation was completed in April 2004.[184][185] At the same time, the museum announced that it would revert to its previous name, Brooklyn Museum.[188][189] By then, the Brooklyn Museum was focusing on attracting Brooklyn residents, rather than visitors from other boroughs.[184] The Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art opened on the museum's fourth floor in March 2007.[190][191]

The museum extensively renovated its Great Hall, which reopened in early 2011,

The museum was temporarily closed from March to October 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City.[204] During the George Floyd protests in New York City in June 2020, the museum participated in the Open Your Lobby initiative, being one of two major art institutions in New York City (along with MoMA PS1) to provide protesters with shelter or resources.[205] The Brooklyn Museum received $50 million from the New York City government in 2021, the largest such gift in the museum's history.[206][207] The money was to be used to renovate 40,000 square feet (3,700 m2) into gallery space,[208] and the museum hired Brigham Keener to design the new galleries.[209] The museum's South Asian and Islamic galleries reopened in 2022, completing a 12-year renovation of the Asian galleries.[210][211] To make way for additional exhibition space, in early 2024 the museum sold off 200 objects and the contents of four period rooms.[212]

Building

The Brooklyn Museum building is a steel frame structure clad in masonry, designed in the

Exterior

The original design for the Brooklyn Museum proposed a structure four times as large as what was built from 1893 through 1927, when construction ended.

Main facade

The primary

The pavilions at either end of the Eastern Parkway facade protrude only slightly from the facade and contain engaged columns in the Ionic order. The west and east wings are divided vertically by pilasters; between each set of pilasters are windows with architraves. The entablature above the pilasters contains a frieze with inscribed names of figures who represent knowledge.[217]: 2

The Eastern Parkway facade is topped by 20 monolithic figures on the cornice: one above each pilaster on the west and east wings, and four above the pavilions.[217]: 2 An additional ten figures, five each on the western and eastern elevations of the outermost pavilions, were sculpted.[221] The sculptures were carved by the Piccirilli Brothers, who sculpted a total of 30 figures on the museum's facade.[222][223] Fourteen sculptors were hired to design the sculptures, which each measure 12 feet (3.7 m) high. Had the full building been completed, there would have been 80 sculptures in total, with 20 each depicting classical subjects, medieval and Renaissance subjects, modern European and American subjects, and Asian subjects. The 30 extant sculptures consist of the 20 classical sculptures (10 Greek and 10 Roman) on the northern elevation, as well as five Persian and five Chinese sculptures on the side elevations.[221]

Other facades

The eastern elevation of the facade faces Washington Avenue, where only the pavilion at the northern end was built. The rest of the eastern elevation is similar to that on Eastern Parkway, with pilasters dividing it vertically into seven bays. Unlike on Eastern Parkway, the pilasters are topped by shorter pilasters rather than sculptures.[217]: 2 The southern elevation faces a parking lot and contains a masonry facade and some windows.[217]: 3 There is also an annex to the south, designed by Brown, Lawford & Forbes, which contains a secondary entrance and a stairway.[8][217]: 3

Interior

The oldest portion of the building measured 193 by 71 feet (59 by 22 m) and comprised only about three percent of what was originally planned. The center of the first floor would have contained a memorial hall, while a "great hall of sculpture" would have extended to the north and south of the memorial hall. To the west of the memorial hall would have been gallery space for artwork on loan, while to the east would have been a multi-story auditorium. The remaining corners of the first floor would have included several additional galleries for the museum's permanent collections, and the light courts would have exhibited large objects. The second floor would have housed more collections and lecture rooms, while the third floor would have had the library, music room, and galleries for images, domestic art, and science. An additional story, above the central part of the building, would have housed more departments of the museum.[11]

The main lobby, originally occupied by the ground-level auditorium, was built during the mid-20th century as a modern-style space.

Operations

The Brooklyn Museum is operated by a nonprofit of the same name, which was established in 1935.[225] The museum is part of the Cultural Institutions Group (CIG), a group of institutions that occupy land or buildings owned by the New York City government and derive part of their yearly funding from the city.[226] It was also part of the Brooklyn Educational Cultural Alliance during the late 20th century.[227] During the late 1980s, the museum was part of a group called Destination Brooklyn, which sought to attract visitors to Brooklyn;[228] this initiative had stalled by the early 1990s.[229]

Directors

Franklin Hooper was the Brooklyn Institute's first director, serving for 25 years until his death in 1914.[230] Hooper was succeeded by William Henry Fox, who served from 1914 to his retirement in 1934.[231][232] Fox was followed by Philip Newell Youtz from 1934 to 1938.[233][234] Laurance Page Roberts was director from 1938 to 1942, when his wife Isabel Spaulding Roberts became interim director on his behalf;[235] L. P. Roberts formally resigned in 1946.[236][237] His immediate successor, Charles Nagel Jr., served for nine years until he resigned in 1955.[238] Edgar Craig Schenck, who was appointed director shortly afterward,[239] served until his death in 1959.[240][241] Thomas S. Buechner became the museum's director in 1960,[242][243] making him one of the youngest directors in the country.[244] During Buechner's tenure, Donelson Hoopes was hired as Curator of Paintings and Sculptures from 1965 to 1969.[245]

Duncan F. Cameron assumed the directorship in 1971, following Buechner's resignation;[246] Cameron himself resigned in 1973.[132][133] Michael Kan was appointed as acting director in early 1984,[247] serving for a few months.[134] He was succeeded by Michael Botwinick, who was appointed in 1974[248] and stepped down in 1982.[249] Robert T. Buck became director in 1983[250] and served until he resigned in 1996, upon which Linda S. Ferber became acting director.[251] From 1992 to 1995, Stephanie Stebich was Buck's assistant director.[252] Arnold L. Lehman was named as the museum's director in April 1997,[253] and Lehman announced in September 2014 that he would retire the next year.[254] In May 2015, Creative Time president and artistic director Anne Pasternak was named the museum's next director;[255] she assumed the position on September 1, 2015.[256]

Since 2014, the director's position has formally been known as the Shelby White and Leon Levy Director of the Brooklyn Museum, after Leon Levy Foundation cofounder Shelby White donated $5 million to the directorship's endowment.[257][258]

Funding

According to the museum's website, it receives funding from the

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Brooklyn Museum had an endowment of $108 million, but the museum applied for federal funding through the Paycheck Protection Program after its endowment declined by one-fifth in 2020.[263] Amid the pandemic and its negative impact on museum revenue, the museum raised funds for an endowment to pay for collections care by selling or deaccessioning works of art. The October 2020 sale consisted of 12 works by artists including Lucas Cranach the Elder, Gustave Courbet, and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot,[264] while other sales throughout that month included Modernist artists.[265] Though usually prohibited by the Association of Art Museum Directors, the association allowed such sales to proceed for a two-year window through 2022 in response to the effects of the pandemic.[266]

Art and exhibitions

The Brooklyn Museum's collection contains around 500,000 objects.[2] In the twentieth century, Brooklyn Museum exhibitions sought to present an encyclopedic view of art and culture, with a focus on educating a broad public.[3] In 1923, the museum was one of the first U.S. institutions to exhibit African cast-metal and other objects as art, rather than as ethnological artifacts.[267][268] The museum's acquisitions during this time also included such varied objects as the interior of a Swiss house,[269] a stained glass window,[270] and a pipe organ.[271] The museum's first period room opened in 1929; these period rooms represented middle-class and non-elite citizens' homes, in contrast to other museums. which tended to focus on upper-class period rooms.[272] The 17th-century Jans Martense Schenck house became part of the Brooklyn Museum's collection in the 1950s,[273] as did the interior of a room in John D. Rockefeller Jr.'s Midtown Manhattan home.[274]

In 1967 the Federated Institutes of Cultural Enrichment (FICE), a coalition of Brooklyn-based arts organizations, demanded that the Brooklyn Museum exhibit more works by artists from the borough, especially African American artists.[122][275][276] The museum then hired black curator Henri Ghent to direct a new "Community Gallery", supported at first by the New York State Council on the Arts;[122] he worked at the museum till 1972.[277] Ghent's first exhibition, Contemporary Afro-American Arts (1968), included artists Joe Overstreet, Kay Brown, Frank Smith, and Otto Neals.[123][278]

In 1999–2000, the

In 2002, the museum received the work The Dinner Party, by feminist artist Judy Chicago, as a gift from The Elizabeth A. Sackler Foundation. Its permanent exhibition began in 2007, as a centerpiece for the museum's Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art. In 2004, the Brooklyn Museum featured Manifest Destiny, an 8-by-24-foot (2.4 m × 7.3 m) oil-on-wood mural by Alexis Rockman that was commissioned by the museum as a centerpiece for the second-floor Mezzanine Gallery and marked the opening of the museum's renovated Grand Lobby and plaza.[283][284] Other exhibitions have showcased the works of various contemporary artists including Patrick Kelly, Chuck Close, Denis Peterson, Ron Mueck, Takashi Murakami, Mat Benote,[285] Kiki Smith, Jim Dine, Robert Rauschenberg, Ching Ho Cheng, Sylvia Sleigh William Wegman, Jimmy de Sana, Oscar yi Hou, Baseera Khan, Loraine O'Grady, John Edmonds, Cecilia Vicuña, and a 2004 survey show of work by Brooklyn artists, Open House: Working in Brooklyn.[286]

In 2008, curator Edna Russman announced that she believes 10 out of 30 works of Coptic art held in the museum's collection—second-largest in North America are fake. The artworks were exhibited starting in 2009.[287] Costumes from The Crown and The Queen's Gambit television series were put on display as part of its virtual exhibition "The Queen and the Crown" in November 2020.[288][289] From June through September 2023, coinciding with the fiftieth anniversary of Pablo Picasso's death, the museum hosted It's Pablo-matic: Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby, curated by Hannah Gadsby.[290][291] To celebrate the 200th anniversary of the Brooklyn Apprentices' Library's incorporation, the museum launched a series of special exhibits and events in 2024.[292]

Collections

Egyptian, Classical, and Ancient Near Eastern Art

The Brooklyn Museum has been building a collection of

The Egyptian, Classical, and Ancient Near Eastern collections are housed in a series of galleries in the museum. Egyptian artifacts can be found in the long-term exhibit, Egypt Reborn: Art for Eternity, as well as in the Martha A. and Robert S. Rubin Galleries. Near Eastern artifacts are located in the Hagop Kevorkian Gallery.[293]

Selections from the Egyptian collection

-

The "Bird Lady" sculpture, Predynastic female figurine

-

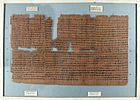

Book of the Dead of the Goldworker of Amun, Sobekmose, 31.1777e

-

Brooklyn Papyrus, 664–332 BCE

-

Painting of Lady Tjepu, New Kingdom Dynasty 18, Reign of Amunhotep III, c. 1390–1352 BCE, from tomb no. 181 at Thebes, 65.197

-

Pair statue of husband and wife Nebsen and Nebet-ta. New Kingdom, Dynasty XVIII, reign of Thutmose IV or Amenhotep III, c. 1400–1352 BCE.

American art

Represented in the American art collection are works by artists such as William Edmondson (Angel, date unknown), John Singer Sargent's Paul César Helleu sketching his wife Alice Guérin (ca. 1889); Georgia O'Keeffe's Dark Tree Trunks (ca. 1946), and Winslow Homer's Eight Bells (ca. 1887). Among the most famous works in the collection are Gilbert Stuart's portrait of George Washington and Edward Hicks's The Peaceable Kingdom. The museum also holds a collection by Emil Fuchs.[295]

Works from the American art collection can be found in various areas of the museum, including in the Steinberg Family Sculpture Garden and in the exhibit, American Identities: A New Look, which is contained within the museum's Visible Storage ▪ Study Center.[296] In total, there are approximately 2,000 American Art objects held in storage.[297]

Selections from the American collection

-

Charles Willson Peale, George Washington, c. 1776

-

Samuel Morse, Portrait of John Adams, 1816

-

Edward Hicks, The Peaceable Kingdom, c. 1830–1840

-

John J. Audubon, Wild Turkey, lithograph, c. 1861

-

Eastman Johnson, A Ride for Liberty – The Fugitive Slaves, c. 1862

-

Albert Pinkham Ryder, Evening Glow The Old Red Cow, 1870–1875

-

Albert Pinkham Ryder, The Waste of Waters is Their Field, 1880

-

Winslow Homer, The Northeaster, c. 1883

-

Ralph Albert Blakelock, Moonlight, 1885

-

George Inness, Sunrise, 1887

-

Thomas Eakins, Letitia Wilson Jordan, 1888

-

John Singer Sargent, Paul César Helleu Sketching with His Wife, 1889

-

Mary Cassatt, La Toilette, c. 1889–1894

-

Childe Hassam, Late Afternoon, New York, Winter, c. 1900

-

Thomas Eakins, William Rush Carving his Allegorical Figure of the Schuylkill River, 1908

-

William Glackens, Nude with Apple, 1909–1910

-

George Bellows, A Morning Snow – Hudson River, 1910

-

Adolph Weinman, Night, c. 1910

-

Henry Ossawa Tanner, The Arch, c. 1914

-

Georgia O'Keeffe, Blue 1, 1916

-

Marsden Hartley, Landscape, New Mexico, 1916–1920

-

Joseph Rusling Meeker, The Acadians in the Achafalaya, "Evangeline", 1871

Asian art

In 2019, the museum reopened its Japanese and Chinese exhibits, after reinstalling its Korean section in 2017.[203] The Chinese section offers pieces from more than 5,000 years of Chinese art and shows contemporary pieces on a regular schedule.[203] The Japanese gallery, with its 7,000 pieces, is the largest of the museum's Asian collection and is known for its works from the Ainu people.[298] The museum is also home to works from Bhutan, India, Nepal, Pakistan and southeast Asia.[299]

Arts of Africa

The oldest acquisitions in the African art collection were collected by the museum in 1900, shortly after the museum's founding.[300] The collection was expanded in 1922 with items originating largely in what is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The next year, the museum hosted one of the first exhibitions of African art in the United States.[301]

With more than 5,000 items in its collection, the Brooklyn Museum boasts one of the largest collections of African art in any American art museum. Although the title of the collection suggests that it includes art from all of the African continent, works from Africa are sub-categorized among a number of collections. Sub-Saharan art from West and Central Africa are collected under the banner of African Art, while North African and Egyptian art works are grouped with the Islamic and Egyptian art collections, respectively.

The African art collection covers 2,500 years of human history and includes sculpture, jewellery, masks, and religious artifacts from more than 100 African cultures. Noteworthy items in this collection include a carved ndop figure of a Kuba king, believed to be among the oldest extant ndop carvings, and a Lulua mother-and-child figure.[302]

In 2018, the museum drew criticism from groups including Decolonize This Place for its hiring of a white woman as Consulting Curator of African Arts.[303][304]

Selections from the African collection

-

Kuba Ndop portrait

-

Golden rider of the Ashanti region culture in Ghana

Arts of the Pacific Islands

The museum's collection of Pacific Islands art began in 1900 with the acquisition of 100 wooden figures and

Art objects in this collection are crafted from a wide variety of materials. The museum lists "coconut fiber, feathers, shells, clay, bone, human hair, wood, moss, and spider webs"[305] as among the materials used to make artworks that include masks, tapa cloths, sculpture, and jewellery.

Arts of the Islamic world

The museum also has art objects and historical texts produced by Muslim artists or about Muslim figures and cultures.[306]

Selections from the Islamic world collection

-

Shahnama of Ferdowsi

-

Zumurrud Shah Takes Refuge in the Mountains, ca. 1570

-

Mihr 'Ali (Iranian, active ca. 1800–1830). Portrait of Fath-Ali Shah Qajar, 1815.

-

Muhammad Hasan (Persian, active 1808–1840). Prince Yahya, ca. 1830s.

-

Bowl with Kufic inscription, 10th century

The Jarvis Collection of Native American Plains Art

The Museum has a collection of Native America Artifacts acquired by Dr. Nathan Sturges Jarvis (surgeon) who was stationed at Fort Snelling, Minnesota 1833–1836.[307]

-

Inlaid pipe bowl with two faces collected at Fort Snelling 1833-1836

Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art

The museum's center for feminist art opened in 2007.[308][191] Spanning 8,300 square feet (770 m2),[191] it is dedicated to preserving the history of the movement since the late 20th century, as well as raising awareness of feminist contributions to art, and informing the future of this area of artistic dialogue. Along with an exhibition space and library, the center features a gallery housing a masterwork by Judy Chicago, a large installation called The Dinner Party (1974–1979).[190]

European art

The Brooklyn Museum has among others late Gothic and Early

Selections from the European collection

-

Lorenzo di Niccolò, Saint Lawrence Buried in Saint Stephen's Tomb, 1410–1414, tempera and tooled gold on poplar, 33 × 36 cm

-

Sano di Pietro, Triptych of Madonna with Child, St. James and St. John the Evangelist, c. 1460 and 1462

-

William Blake (British, 1757–1827) The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun (Rev. 12: 1–4), ca. 1803–1805

-

Eugène Delacroix, Desdemona Cursed by her Father (Desdemona maudite par son père), c. 1850–1854

-

Honoré Daumier, The Two Colleagues (Lawyers) (Les deux confrères Avocats), between 1865 and 1870

-

Gustave Courbet, The Edge of the Pool, 1867

-

Edgar Degas, Portrait de Mlle Eugénie Fiocre, 1867–1868

-

Alfred Sisley, Flood at Moret (Inondation à Moret), 1879

-

Gustave Caillebotte, Apple Tree in Bloom (Pommier en fleurs), c. 1885

-

Jules Breton, Fin du travail (The End of the Working Day), c. 1886–1887

-

Vincent van Gogh, Cypresses (Les Cyprès), 1889, reed pen, graphite, quill, brown ink and black ink on white wove latune et cie balcons paper

-

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, At the Moulin Rouge (Au Moulin Rouge), c. 1892

-

Claude Monet, The Church at Vernon, 1894

-

Claude Monet, Houses of Parliament Sunlight Effect (Le Parlement effet de soleil), 1903

-

Claude Monet, The Doge's Palace (Le Palais ducal), 1908

-

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Les Vignes à Cagnes, 1908

-

André Derain, Landscape in Provence (Paysage de Provence), c. 1908

Other collections

The museum's costume collection was created in 1946,[309] and the Textile and Costume Collection was unveiled in 1977.[310] The collection, composed of American and European attire, was described by The New York Times as "one of the best in the world".[309] Removed from public display in 1991,[311] the collection was transferred to the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Costume Institute in 2008.[309][312]

The Brooklyn Museum has had a photography collection since the 19th century. The museum initially did not seek out photographs for its collection, which was initially composed exclusively of photographers' and collectors' gifts.[313] Since 1993, the collection has been part of the Department of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs.[314]

Libraries and archives

The Brooklyn Museum Libraries and Archives hold approximately 300,000 volumes and over 3,200 feet (980 m) of archives. The collection began in 1823 and is housed in facilities that underwent renovations in 1965, 1984 and 2014.[315][316][317]

Programs

The first Saturday of each month, the Brooklyn Museum stays open until 11 pm, and general admission is waived after 5 pm, although some ticketed exhibitions may require an entrance fee. Regular first Saturday activities include educational family-oriented activities such as collection-based art workshops, gallery tours, lectures, live performances dance parties.[318] The museum started hosting First Saturdays in October 1998,[319] and the event had attracted 1.5 million total visitors as of 2023[update].[320]

As part of the Museum Apprentice Program, the museum hires teenage high schoolers to give tours in the museum's galleries during the summer, assist with the museum's weekend family programs throughout the year, participate in talks with museum curators, serve as a teen advisory board to the museum, and help plan teen events.[321] The museum also runs the Museum Education Fellowship Program, a ten-month position where fellows lead school group visits with a focus on various topics from the collection.[322] School Youth and Family Fellows teach Gallery Studio Programs and School Partnerships while Adult and Public Programs Fellows curate and organize Thursday night as well as First Saturday Programming.[322]

The museum has posted many pieces to a digital collection that allows the public to tag and curate sets of objects online, as well as solicit additional scholarship contributions.[323] The museum's ASK App allows visitors to talk with staff and educators about works in the collection.[324][325]

Attendance

Prior to World War II, the museum offered free admission and regularly attracted over a million annual visitors.[176] In 1934, the museum reported 940,000 annual visitors, while its library had 40,000 visitors.[326] Patronage declined along with Brooklyn's economy in the mid-20th century;[176] there were about 470,000 visitors per year by the early 1950s.[93] The museum recorded 1 million visitors in 1971 for the first time in almost four decades.[327] During the mid-1980s, the museum had 300,000 visitors per year, much less than the Museum of Modern Art or the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan.[151] Annual attendance at the museum, which had stagnated at 250,000 in the mid-1990s, had nearly doubled by 1999 after the museum held several popular exhibits,[182] peaking at 585,000 in 1998.[328] The museum only had 326,000 visitors by 2009,[328] but attendance had increased to 465,000 by 2017.[202]

The New York Times attributed the drop in attendance partially to the policies instituted by then-current director Arnold Lehman, who has chosen to focus the museum's energy on "populism", with exhibits on topics such as "

According to the Times:The quality of their exhibitions has lessened", said Robert Storr, the dean of the Yale University School of Art and a Brooklynite. "'Star Wars' shows the worst kind of populism. I don't think they really understand where they are. The middle of the art world is now in Brooklyn; it's an increasingly sophisticated audience and always was one.[328]

On the other hand, Lehman says that the demographics of museum attendees are showing a new level of diversity. According to The New York Times, "the average age [of museum attendees in a 2008 survey] was 35, a large portion of the visitors (40 percent) came from Brooklyn, and more than 40 percent identified themselves as people of color."[330] Lehman states that the museum's interest is in being welcoming and attractive to all potential museum attendees, rather than simply amassing large numbers of them.[330]

As of 2023[update], the Brooklyn Museum has a pay what you want policy for general-admission tickets.[331] Half of patrons did not pay any admission in 2017.[202]

Works and publications

- Choi, Connie H.; Hermo, Carmen; Hockley, Rujeko; Morris, Catherine; Weissberg, Stephanie (2017). Morris, Catherine; Hockley, Rujeko (eds.). OCLC 964698467. – Published on the occasion of an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, April 21 – September 17, 2017

See also

- Brooklyn Visual Heritage

- Education in New York City

- List of cases argued by Floyd Abrams

- List of museums and cultural institutions in New York City

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Brooklyn

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Brooklyn

References

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ from the original on January 28, 2022. Retrieved July 2, 2023.

- ^ from the original on July 25, 2023. Retrieved June 15, 2023.

- ^ Spelling, Simon. "Entertainment: Brooklyn Museum". New York. Archived from the original on May 8, 2012. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-670-11139-8.

- ^ a b Weeks, S.B. (1894). A Preliminary List of American Learned and Educational Societies. p. 1526.

- from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ from the original on July 27, 2019. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ a b c "About: The Museum's Building". Brooklyn Museum. Archived from the original on February 21, 2021. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ ProQuest 126805239.

- ^ "For Art and Science". The Standard Union. February 6, 1889. p. 4. Archived from the original on July 2, 2023. Retrieved July 2, 2023.

- ^ "An Art Museum". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. February 6, 1889. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 2, 2023. Retrieved July 2, 2023.

- ^ "New Museums of Art". The Brooklyn Citizen. March 17, 1889. p. 7. Archived from the original on July 2, 2023. Retrieved July 2, 2023.

- ^ "The Brooklyn Institute". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. June 9, 1891. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 2, 2023. Retrieved July 2, 2023.

- ProQuest 573996298.

- ProQuest 574014116.

- ^ a b "Institute Park". The Brooklyn Citizen. June 1, 1895. p. 6. Archived from the original on July 2, 2023. Retrieved July 2, 2023.

- ^ "Museum Plans". The Standard Union. June 1, 1895. p. 3. Archived from the original on July 2, 2023. Retrieved July 2, 2023.

- ProQuest 574038500.

- from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ProQuest 574081465.

- ^ "Noble Monument". The Brooklyn Citizen. December 14, 1895. pp. 1, 6. Archived from the original on July 2, 2023. Retrieved July 2, 2023.

- from the original on July 2, 2023. Retrieved July 2, 2023.

- ProQuest 574167414.

- ProQuest 574278771.

- ProQuest 574319190.

- ProQuest 574349508.

- from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ ProQuest 574611963.

- ^ "The Institute Museum Building". The Brooklyn Citizen. June 9, 1899. p. 9. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ "Main Section of the Museum". The Standard Union. June 9, 1899. p. 5. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ a b c "New Museum Wing". The Brooklyn Citizen. June 4, 1900. p. 10. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ a b "The News of Brooklyn". New-York Tribune. June 10, 1900. p. 24. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ a b "Institute's New Part". New-York Tribune. August 28, 1904. p. 20. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ "Walton Urges Haste". The Brooklyn Citizen. November 17, 1899. p. 9. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ "Ground Broken for New Section of Institute". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. June 7, 1900. p. 15. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ProQuest 571236596.

- from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ProQuest 572067208.

- ProQuest 571953389.

- ^ "Eastern Wing of Institute Museum Formally Dedicated". The Standard Union. December 15, 1907. p. 4. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ "Ready to Dedicate New Museum Wing". Times Union. December 7, 1907. p. 4. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ProQuest 508046466.

- ^ "Another $25,000 Gift to Brooklyn Institute". The Brooklyn Citizen. June 11, 1905. p. 6. Archived from the original on July 23, 2023. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- ^ "Two Great Gifts to Brooklyn Institute". Times Union. June 10, 1905. p. 4. Archived from the original on July 24, 2023. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ^ "City to Pay $25,000 a Year for Observatory in Prospect Park". The Standard Union. July 14, 1907. p. 17. Archived from the original on July 24, 2023. Retrieved July 24, 2023.

- ^ a b "Addition to Museum to Be Built Shortly". The Chat. June 3, 1911. p. 4. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ProQuest 574758676.

- ProQuest 574788579.

- ^ "Brooklyn Institute Shows Great Growth". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. October 18, 1911. p. 8. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ "Brooklyn Institute Valued at $2,937,046". Times Union. October 19, 1911. p. 18. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ "... Work on Road Back of Museum". The Standard Union. November 22, 1911. p. 6. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ "Delay on Museum Wing". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. November 11, 1913. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ "Request for Funds to Finish Museum Is Again Refused". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 28, 1923. p. 2. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- ^ a b "Art Treasures Lost to Museum by Delay on Finishing Wing". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. July 16, 1916. p. 13. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ "Subway Stations Opened: Last Three in Eastern Parkway Branch of I.R.T. Put Into Service" (PDF). The New York Times. October 11, 1920. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 26, 2022. Retrieved December 20, 2015.

- ^ "Bill for Central Library and Museum Wing Bond Issue Signed by Miller". Times Union. April 7, 1922. p. 4. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ "Delay Museum Wing Until Late in Fall". The Standard Union. July 13, 1922. p. 3. Archived from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ "Hylan Holds Up $950,000 Fund for Brooklyn Museum". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 13, 1923. p. 24. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- ^ "Estimate Board Votes $1,050,000 for Boro Museum". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. June 4, 1923. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- ^ "To Resume Work on Museum When Board Approves". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. September 9, 1923. p. 37. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- ^ "Brooklyn Museum's New Wings Will Soon Be Finished; Great Art Treasures Ready to Fill Extension". Times Union. September 9, 1923. p. 10. Archived from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ Appleton Read, Helen (November 22, 1925). "Brooklyn Museum Inaugurates New Wing With American Exhibition". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. p. 72. Archived from the original on July 19, 2023. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ProQuest 1677044361.

- ^ "New Ethnological Gallery Dedicated". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. December 9, 1925. p. 3. Archived from the original on July 19, 2023. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- from the original on July 19, 2023. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- from the original on July 19, 2023. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ "Museum Opens 3 Permanent Art Galleries". Times Union. May 8, 1927. p. 69. Archived from the original on July 21, 2023. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ "Three New Galleries Open at Brooklyn Museum Today". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 8, 1927. p. 73. Archived from the original on July 19, 2023. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ Appleton Read, Helen (December 1, 1929). "An All-American Opening". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. p. 64. Archived from the original on July 19, 2023. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ "Rebuilt Museum Entrance Will Not Have Long Steps". Times Union. May 10, 1934. p. 3. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ^ ProQuest 1222340168.

- ^ "500 PWA Workers at Museum Stage 3-Hour Pay Strike". Times Union. October 4, 1935. p. 4. Archived from the original on July 5, 2023. Retrieved July 5, 2023.

- ^ Byck, Lester L. (February 10, 1935). "Brooklyn Museum's Gallery Devoted to Work of Living Artists Opens Soon". Times Union. p. 3. Archived from the original on July 19, 2023. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- from the original on July 19, 2023. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ "Persian Gallery at Museum Opens With Loan Exhibition". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. April 7, 1935. p. 39. Archived from the original on July 20, 2023. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ "New Entrances and Hall of Brooklyn Museum Opened to Public". The Brooklyn Citizen. October 5, 1935. p. 3. Archived from the original on July 20, 2023. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ^ "Brooklyn Museum Exhibits Old Art". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. December 6, 1935. p. 2. Archived from the original on July 20, 2023. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- from the original on July 19, 2023. Retrieved July 19, 2023.

- ProQuest 1653382463.

- ProQuest 1243640786.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ^ from the original on February 8, 2022. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ProQuest 1320074766.

- ^ "Art Distribution Center to Be Opened in Boro". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. January 30, 1941. p. 19. Archived from the original on July 21, 2023. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ProQuest 1564926735.

- from the original on July 21, 2023. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ "Museum Plans Spur Boro Cultural Center". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. January 11, 1949. p. 3. Archived from the original on July 21, 2023. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ from the original on July 21, 2023. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- from the original on July 21, 2023. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ from the original on July 21, 2023. Retrieved July 21, 2023.

- ^ "Academy of Music Saved for Public". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. June 22, 1951. pp. 1, 11. Archived from the original on July 23, 2023. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- ProQuest 1324187503.

- from the original on July 23, 2023. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- ^ "Boro Museum Modernizes Fabulous Egyptian Galleries". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. November 17, 1953. p. 9. Archived from the original on July 23, 2023. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- from the original on July 23, 2023. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- from the original on July 2, 2023. Retrieved July 2, 2023.

- ^ ProQuest 1326289458.

- ^ "New Galleries to Open". Daily News. January 28, 1957. p. 333. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- from the original on July 23, 2023. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- ^ "An Old-Timer Intrigues Diane". Daily News. April 15, 1959. p. 456. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ProQuest 1327054968.

- ProQuest 1565234557.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ProQuest 1326285567.

- ^ "Plan to Expand Art Gallery of Brooklyn Museum". Brooklyn Record. June 26, 1964. p. 7. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- from the original on July 23, 2023. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- ^ "Art of Indians on Display at Boro Museum". Daily News. May 2, 1965. p. 203. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ^ "Garden of Memories". Newsday (Nassau Edition). April 27, 1966. p. 102. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 4, 2023.

- ProQuest 226784000.

- ^ from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved June 15, 2023.

- ^ ProQuest 147830601.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 3, 2023.

- ProQuest 148166722.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 3, 2023.

- ^ a b Herzig, Doris (October 26, 1971). "Art Deco Makes It—to the Museum". Newsday. pp. 84, 85. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ProQuest 226720450.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ^ from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ^ ProQuest 1240163688.

- ^ ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ^ "Museum is Picketed by Friendly Staffers". Daily News. March 4, 1974. p. 273. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ^ "Boro Briefs". Daily News. October 7, 1974. p. 246. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ProQuest 226616695.

- ProQuest 122780877.

- ^ from the original on July 3, 2023. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- ^ Wallach, Amei (August 6, 1978). "Forging the Brooklyn-Cairo connection". Newsday. pp. 89, 90. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ^ "Cutbacks Voted by Brooklyn Museum". The New York Times. July 9, 1979. Archived from the original on July 1, 2023. Retrieved July 1, 2023.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 4, 2023.

- from the original on July 2, 2023. Retrieved July 2, 2023.

- ^ a b "Museum budget picture far from pretty". Daily News. April 25, 1980. p. 488. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ^ from the original on July 7, 2023. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- ProQuest 277964505.

- ^ a b "Canarsie's Schenck House Period Rooms On Display Now at Brooklyn Museum". Canarsie Courier. November 1, 1984. pp. 3, 52. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 5, 2023.. Newsday. September 18, 1984. p. 130. Retrieved October 5, 2023.

- "The Brooklyn Museum Adds an Extra Day to Its Weekly Schedule"

External links

- Official website

- Brooklyn Museum records, 1823–1963 from the Smithsonian Archives of American Art.

- Brooklyn Museum Building Online Exhibition

- The Brooklyn Museum collection at the Internet Archive