Enchanted forest

In

Folktales

The forest as a place of magic and danger is found among folklore wherever the natural state of wild land is forest: a forest is a location beyond which people normally travel, where strange things might occur, and strange people might live, the home of

Indeed, in

Even in folklore, forests can also be places of magical refuge.

At other times, the marvels they meet are beneficial. In the forest, the hero of a fairy tale can meet and have mercy on

The creatures of the forest need not be magical to have much the same effect; Robin Hood and the Green Man, living in the greenwood, has affinities to the enchanted forest.[21] Even in fairy tales, robbers may serve the roles of magical beings; in an Italian variant of Snow White, Bella Venezia, the heroine takes refuge not with dwarfs but with robbers.[22]

Mythology

The danger of the folkloric forest is an opportunity for the heroes of legend. Among the oldest of all recorded tales, the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh recounts how the heroes Gilgamesh and Enkidu traveled to the Cedar Forest to fight the monsters there and be the first to cut down its trees. In Norse myth and legend, Myrkviðr (or Mirkwood) was dark and dangerous forest that separated various lands; heroes and even gods had to traverse it with difficulty.[23]

Romans referred to the Hercynian Forest, in Germania, as an enchanted place; though most references in their works are to geography, Julius Caesar mentioned unicorns said to live there, and Pliny the Elder, birds with feathers that glowed.

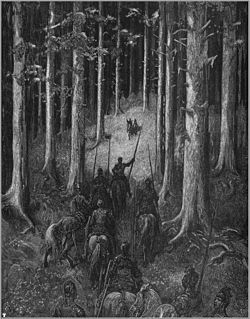

Medieval romance

The figure of an enchanted forest was taken up into

This forest could easily bewilder the knights. Despite many references to its pathlessness, the forest repeatedly confronts knights with forks and crossroads, of a labyrinthine complexity.[30] The significance of their encounters is often explained to the knights – particularly those searching for the Holy Grail – by hermits acting as wise old men – or women.[31] Still, despite their perils and chances of error, such forests are places where the knights may become worthy and find the object of their quest; one romance has a maiden urging Sir Lancelot on his quest for the Holy Grail, "which quickens with life and greenness like the forest."[32] Dante Alighieri used this image in the opening of the Divine Comedy story Inferno, where he depicted his state as allegorically being lost in a dark wood.[33]

Renaissance works

In the Renaissance, both

While these works were being written, expanding geographical knowledge, and the decrease of

Known inhabitants and traits

Often forests will be the home of dragons, dwarves, elves, vampires, werewolves, fairies, nymphs, giants, gnomes, satyrs, goblins, orcs, trolls, slugfolk, dark elves, leprechauns, halflings, centaurs, half-elves, dragonfolk, and unicorns.

In the modern era, people have reported alleged sightings of various cryptids living within the forest such as the Bigfoot and the Pope Lick Monster to name a few.

There may be trees that talk or with branches that will push people off their horses, thorny bushes which will open to let people in but close and leave people stuck inside, and other plants that move or turn into animals at night, or the like.

Some stories have powerful sorcerers, wizards, and witches, both good and evil living somewhere in the depths of the forest.

In some stories the forest itself was sometimes described as being almost alive and sapient in some shape or form instinctively protecting itself and its inhabitants whenever it senses danger approaching. In other stories it appears to be capable of cutting itself off almost entirely from the outside world for long periods of time preventing anyone from going in or out.

In more recent years, there have been several horror films that have taken the concept of the Enchanted Forest and have made their own spins on it. Arguably the most notable example of this is in the Wrong Turn franchise in which the forest is populated by various families of deformed cannibals who hunt and kill large groups of people in horrific ways by using a mixture of traps and weaponry. The reboot film features a centuries-old cult who respond violently to outsiders who intrude on their self-sufficient civilization.

Modern fantasy

The use of enchanted forests shaded into modern fantasy with no distinct breaking point, stemming from the very earliest fantasies.[35]

- In George MacDonald's Phantastes, the hero finds himself in a wood as dark and tangled as Dante's, una selva oscura that blots out sunlight and is utterly still, without any beasts or birdsong.[35]

- The more inviting but no less enchanted forest in The Golden Key borders Fairyland and draws the hero to find the title key at the end of the rainbow.[36]

- In The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, L. Frank Baum depicted the wild and dangerous parts of the Land of Oz as being forested, and indeed, inhabited with animated trees with human-like traits, a common feature in children's literature.[37]

- William T. Cox in his 1910 work Fearsome Creatures of the Lumberwoods based the entire book off of actual forests across North America; however, the author combines these factual locations with fantastic encounters between lumberjacks and mysterious creatures.[38]

- In Winnie the Pooh, the Hundred Acre Wood is a beautifully scenic forest home to Winnie the Pooh and all of his friends.

- Following J.R.R. Tolkien's work, the enchanted forest is often a magical place in modern fantasy. It continues to be a place unknown to the characters, where strange dangers lurk.[44]

- The Enchanted Forest is particularly close to folklore in fairytale fantasy, featuring in such works as James Thurber's The White Deer and The 13 Clocks.[45]

- In the contemporary fantasy Harry Potter books, the Forbidden Forest near Hogwarts is forbidden because of its magical nature. The home of unicorns, centaurs, and Acromantulas (a race of giant spiders), it continues the tradition of the forest as a place of wild things and danger.[46]

- In Suzanna Clarke's Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, the Raven King's capital city of Newcastle in Northern England was surrounded by four magical woods, with names like Petty Egypt, and St. Sirlow's Blessing. These forests were supposedly enchanted by the Raven King himself to defend his city. They could move around, and supposedly devoured approaching people intending to harm the city. Clarke brings the notion of magical places to life by contrasting this historical account within the story itself, to the actual depictions of magical woods within the story, where the trees themselves can be regarded as friend or foe, and have formed alliances with magicians.[47]

- In My Neighbor Totoro, the forest home of the Totoros is an idyllic place where no harm will come to the heroines of the movies.[48]

- There are variations on enchanted forests in the Spyro series. The Artisans Homeworld In Spyro the Dragon, as well as Summer Forest and Autmn Plains in Spyro 2: Ripto's Rage!, and Sunrise Spring from Spyro: Year of the Dragon are all different forms of magical forests that act as homeworlds.

- In contrast, in the Touhou Project series by Team Shanghai Alice, the Forest of Magic is an extremely dangerous place crawling with youkai.

- In sprites.

- In Naruto, the Forty-Fourth Training Ground, more commonly known as the Forest of Death, is a strange forest filled with hordes of flora and fauna, often gigantic, poisonous — or even more likely, both — hence its name.

- In Evil Queen and her followers brought them to the Land Without Magic. There is a desert that separates the land from Agrabah, while also being separated from Arendelle, DunBroch, and the Oceanic Realm by seas and a few days ride from Camelot and the Empire. The land is also seen in the series' spin-off Once Upon a Time in Wonderland. During the seventh and final season, the New Enchanted Forest is introduced as its main setting. It is located in New Fairy Tale Land and is separated from Maldonia and New Agrabah and has its version of Wonderlandcalled New Wonderland. This version has elements from the 18th and 19th century mixed with small elements from the Middle Ages as well as French influences. In addition, there is a hierarchy in the kingdoms like a "federal" kingdom and "federated" kingdoms as the unnamed King seems to rule all over the New Enchanted Forest. It is because of the king and Lady Rapunzel Tremaine that there is a resistance against them. By the end of the series, both Enchanted Forests become part of the United Realms upon combining with Storybrooke, the other Fairy Tale Land locations, the Land of Oz, the Land of Untold Stories, Neverland, and the Wish Realm.

- The Enchanted Forest is featured in Ever After High. It is a location in the Fairytale World that is located next to Ever After High and the Village of Book End. The students of Ever After High hang out there often....Especially when the students need time alone. For this purpose, there's a gazebo located deep in the forest.

- In My Little Pony: Friendship is Magic, the Everfree Forest is depicted as an enchanted forest grove adjacent to Ponyville. The forest is largely uninhabitable, being a saturated "hotspot" of unpredictable wild magic induced genetic mutations and dangerous legendary creatures and is regarded by ponies as the most hostile region within Equestria's borders.

- In Frozen 2, the Enchanted Forest is home to spirits of fire, earth, wind and water. Elsa journeys there to find the origins of her powers and end the feud between Arendalle and the forests native people.

- In Mickey Mouse Funhouse, there is a variation of the enchanted forest called the Enchanted Rainforest. It is depicted as being sentient and consists of different jungle animals. The Enchanted Rainforest was first visited in the episode "Minnie Goes Ape" where Minnie Mouse had to return Pinky the Gorilla (vocal effects provided by Kaitlyn Robrock) to her parents.

- In the Pokémonsome friendly some not.

See also

References

- ISBN 0-15-667897-7

- ^ Heidi Anne Heiner, The Annotated Hansel and Gretel Archived 2009-01-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Heidi Anne Heiner,The Annotated Vasilissa the Beautiful

- ^ Joseph Jacobs, "Molly Whuppie Archived 2013-07-18 at the Wayback Machine", English Fairy Tales

- ^ W. F. Kirby, "The Grateful Prince", The Hero of Esthonia

- Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm, "The Three Little Men in the Wood Archived 2014-03-24 at the Wayback Machine" Household Tales

- The Yellow Fairy Book

- ^ Heidi Anne Heiner, The Annotated Brother and Sister Archived 2010-04-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 0-226-32239-4

- ^ a b Andrew Lang, The Violet Fairy Book, "Schippeitaro"

- ISBN 0-312-29380-1

- ^ Paul Delarue, The Borzoi Book of French Folk-Tales, p xvii, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York 1956

- ISBN 0-691-06722-8

- ^ Heidi Anne Heiner, The Annotated Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

- ^ Heid Anne Heiner, The Annotated Girl Without Hands Archived 2013-10-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Max Lüthi, Once Upon A Time: On the Nature of Fairy Tales, p 76, Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., New York, 1970

- ISBN 0-312-29380-1

- ^ "The Famous Flower of Serving-Men"

- ^ Jacob and Wilheim Grimm, "Rumpelstiltskin", Grimm's Fairy Tales

- ^ John Rhys, "Whuppity Stoorie", Celtic Folklore: Welsh and Manx. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1901. Volume 2.

- ^ ISBN 0-500-27541-6.

- ISBN 0-15-645489-0

- ISBN 0-87054-076-9

- ISBN 0-88029-454-X

- ISBN 0-521-47735-2

- ISBN 0-394-73467-X

- ^ Margaret Schlauch, Chaucer's Constance and Accused Queens, New York: Gordian Press 1969 p 91-2

- ^ Laura A. Hibbard, Medieval Romance in England pp. 240-1 New York: Burt Franklin, 1963.

- ^ Margaret Schlauch, Chaucer's Constance and Accused Queens, New York: Gordian Press 1969 p 107

- ISBN 0-8014-8000-0

- ISBN 0-8014-8000-0

- ISBN 0-8014-8000-0

- ISBN 0-8014-8000-0

- ISBN 0-691-01298-9

- ^ ISBN 0-06-250520-3

- ISBN 0-06-250520-3

- ISBN 0-517-50086-8

- ^ Cox, William T. (1910). Fearsome Creatures of the Lumberwoods. Judd & Detweiler Inc.

- ISBN 0-312-19869-8

- ISBN 0-394-73467-X

- ISBN 0-8126-9545-3

- ISBN 0-618-25760-8

- ISBN 0-8126-9545-3

- ISBN 0-87116-195-8

- ISBN 0-253-35665-2

- ISBN 0-9708442-0-4

- ^ Suzanna Clarke, Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, London; Bloomsbury Publishing, 2004.

- ISBN 1-880656-41-8

Further reading

- Hackett, Jon, and Seán Harrington, eds. Beasts of the Forest: Denizens of the Dark Woods. Bloomington, IN, USA: Indiana University Press, 2019. doi:10.2307/j.ctvs32scr.

- Łaszkiewicz, Weronika. "Into the Wild Woods: On the Significance of Trees and Forests in Fantasy Fiction." Mythlore 36, no. 1 (131) (2017): 39–58. doi:10.2307/26809256.

- Maitland, Sara. "From the Forest." New England Review 33, no. 3 (2012): 7-17. www.jstor.org/stable/24242777.

- Post, Marco R.S. "Perilous Wanderings through the Enchanted Forest: The Influence of the Fairy-Tale Tradition on Mirkwood in Tolkien's "The Hobbit"." Mythlore 33, no. 1 (125) (2014): 67–84. doi:10.2307/26815941.