Divination

- Afrikaans

- العربية

- Български

- Català

- Čeština

- Corsu

- Cymraeg

- Dansk

- Deutsch

- Eesti

- Español

- Esperanto

- Euskara

- فارسی

- Français

- Galego

- 한국어

- हिन्दी

- Hrvatski

- Bahasa Indonesia

- Interlingua

- Italiano

- עברית

- Kabɩyɛ

- ქართული

- Кыргызча

- Li Niha

- Magyar

- Македонски

- Bahasa Melayu

- Nederlands

- 日本語

- Norsk nynorsk

- Occitan

- Pangcah

- Polski

- Português

- Runa Simi

- Русский

- Саха тыла

- Sicilianu

- Simple English

- Slovenčina

- Српски / srpski

- Srpskohrvatski / српскохрватски

- Suomi

- Svenska

- Татарча / tatarça

- Türkçe

- Українська

- Tiếng Việt

- 文言

- 粵語

- 中文

| Part of a series on |

| Magic |

|---|

|

|

Related topics |

| Part of a series on |

| Esotericism |

|---|

|

|

Key concepts

|

|

Esoteric rites |

|

Esoteric societies |

Divination (from

Divination can be seen as an attempt to organize what appears to be random so that it provides insight into a problem or issue at hand.

In its functional relation to magic in general, divination can have a preliminary and investigative role:

[...] the diagnosis or prognosis achieved through divination is both temporarily and logically related to the manipulative, protective or alleviative function of magic rituals. In divination one finds the cause of an ailment or a potential danger, in magic one subsequently acts upon this knowledge.[8]

Divination has long attracted criticism. In the modern era, it has been dismissed by the scientific community and by skeptics as being superstitious; experiments do not support the idea that divination techniques can actually predict the future more reliably or precisely than would be possible without it.[9][10] In antiquity, divination came under attack from philosophers such as the Academic skeptic Cicero in De Divinatione (1st century BCE) and the Pyrrhonist Sextus Empiricus in Against the Astrologers (2nd century CE). The satirist Lucian (c. 125 – after 180) devoted an essay to Alexander the false prophet.[11]

History

Antiquity

The Oracle of Amun at the Siwa Oasis was made famous when Alexander the Great visited it after conquering Egypt from Persia in 332 BC.[12]

Deuteronomy 18:10–12 or Leviticus 19:26 can be interpreted as categorically forbidding divination. But some biblical practices, such as Urim and Thummim, casting lots and prayer, are considered to be divination. Trevan G. Hatch disputes these comparisons because divination did not consult the "one true God" and manipulated the divine for the diviner's self-interest.[13] One of the earliest known divination artifacts, a book called the Sortes Sanctorum, is believed to be of Christian roots, and utilizes dice to provide insight into the future.[14]

Uri Gabbay states that divination was associated with sacrificial rituals in the ancient Near East, including Mesopotamia and Israel. Extispicy was a common example, where diviners would pray to their god(s) before vivisecting a sacrificial animal. Their abominal organs would reveal a divine message, which aligned with cardiocentric views of the mind.[15]

Oracles and Greek divination

Both oracles and seers in ancient Greece practiced divination. Oracles were the conduits for the gods on earth; their prophecies were understood to be the will of the gods verbatim. Because of the high demand for oracle consultations and the oracles’ limited work schedule, they were not the main source of divination for the ancient Greeks. That role fell to the seers (Greek: μάντεις).[16]

Seers were not in direct contact with the gods; instead, they were interpreters of signs provided by the gods. Seers used many methods to explicate the will of the gods including

The disadvantage of seers was that only direct yes-or-no questions could be answered. Oracles could answer more generalized questions, and seers often had to perform several sacrifices in order to get the most consistent answer. For example, if a general wanted to know if the omens were proper for him to advance on the enemy, he would ask his seer both that question and if it were better for him to remain on the defensive. If the seer gave consistent answers, the advice was considered valid.[citation needed]

During battle, generals would frequently ask seers at both the

Because the seers had such power over influential individuals in ancient Greece, many were skeptical of the accuracy and honesty of the seers. The degree to which seers were honest depends entirely on the individual seers. Despite the doubt surrounding individual seers, the craft as a whole was well regarded and trusted by the Greeks,[18] and the Stoics accounted for the validity of divination in their physics.

Middle Ages and Early Modern period

| Part of a series on |

| Artes Prohibitae |

|---|

|

The divination method of casting lots (Cleromancy) was used by the remaining eleven disciples of Jesus in Acts 1:23–26 to select a replacement for Judas Iscariot. Therefore, divination was arguably an accepted practice in the early church. However, divination became viewed as a pagan practice by Christian emperors during ancient Rome.[19]

In 692 the Quinisext Council, also known as the "Council in Trullo" in the Eastern Orthodox Church, passed canons to eliminate pagan and divination practices.[20] Fortune-telling and other forms of divination were widespread through the Middle Ages.[21] In the constitution of 1572 and public regulations of 1661 of the Electorate of Saxony, capital punishment was used on those predicting the future.[22] Laws forbidding divination practice continue to this day.[23] The Waldensians sect were accused of practicing divination.[24]

Småland is famous for Årsgång, a practice which occurred until the early 19th century in some parts of Småland. Generally occurring on Christmas and New Year's Eve, it is a practice in which one would fast and keep themselves away from light in a room until midnight to then complete a set of complex events to interpret symbols encountered throughout the journey to foresee the coming year.[25]

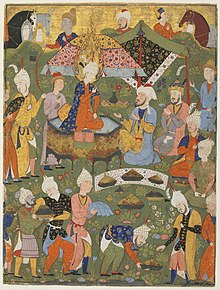

In Islam, astrology (‘ilm ahkam al-nujum), the most widespread divinatory science, is the study of how celestial entities could be applied to the daily lives of people on earth.[26][27] It is important to emphasize the practical nature of divinatory sciences because people from all socioeconomic levels and pedigrees sought the advice of astrologers to make important decisions in their lives.[28] Astronomy was made a distinct science by intellectuals who did not agree with the former, although distinction may not have been made in daily practice, where astrology was technically outlawed and only tolerated if it was employed in public. Astrologers, trained as scientists and astronomers, were able to interpret the celestial forces that ruled the "sub-lunar" to predict a variety of information from lunar phases and drought to times of prayer and the foundation of cities. The courtly sanction and elite patronage of Muslim rulers benefited astrologers’ intellectual statures.[29]

The “science of the sand” (‘ilm al-raml), otherwise translated as geomancy, is “based on the interpretation of figures traced on sand or other surface known as geomantic figures.”[30] It is a good example of Islamic divination at a popular level. The core principle that meaning derives from a unique occupied position is identical to the core principle of astrology.

Like astronomy, geomancy used deduction and computation to uncover significant prophecies as opposed to omens (‘ilm al-fa’l), which were process of “reading” visible random events to decipher the invisible realities from which they originated. It was upheld by prophetic tradition and relied almost exclusively on text, specifically the Qur’an (which carried a table for guidance) and poetry, as a development of bibliomancy.[30] The practice culminated in the appearance of the illustrated “Books of Omens” (Falnama) in the early 16th century, an embodiment of the apocalyptic fears as the end of the millennium in the Islamic calendar approached.[31]

Dream interpretation, or oneiromancy (‘ilm ta’bir al-ru’ya), is more specific to Islam than other divinatory science, largely because of the Qur’an’s emphasis on the predictive dreams of Abraham, Yusuf, and Muhammad. The important delineation within the practice lies between “incoherent dreams” and “sound dreams,” which were “a part of prophecy” or heavenly message.[32] Dream interpretation was always tied to Islamic religious texts, providing a moral compass to those seeking advice. The practitioner needed to be skilled enough to apply the individual dream to general precedent while appraising the singular circumstances.[33]

The power of text held significant weight in the "

In Islamic practice in Senegal and Gambia, just like many other West African countries, diviners and religious leaders and healers were interchangeable because Islam was closely related with esoteric practices (like divination), which were responsible for the regional spread of Islam. As scholars learned esoteric sciences, they joined local non-Islamic aristocratic courts, who quickly aligned divination and amulets with the "proof of the power of Islamic religion."[35] So strong was the idea of esoteric knowledge in West African Islam, diviners and magicians uneducated in Islamic texts and Arabic bore the same titles as those who did.[36]

From the beginning of Islam, there "was (and is) still a vigorous debate about whether or not such [divinatory] practices were actually permissible under Islam,” with some scholars like Abu-Hamid al Ghazili (d. 1111) objecting to the science of divination because he believed it bore too much similarity to pagan practices of invoking spiritual entities that were not God.[37][26] Other scholars justified esoteric sciences by comparing a practitioner to "a physician trying to heal the sick with the help of the same natural principles."[38]

Mesoamerica

Divination was a central component of ancient

Every civilization that developed in

Contemporary divination in Asia

India and Nepal

Theyyam or "theiyam" in Malayalam is the process by which a devotee invites a Hindu god or goddess to use his or her body as a medium or channel and answer other devotees' questions.[41] The same is called "arulvaakku" or "arulvaak" in Tamil, another south Indian language - Adhiparasakthi Siddhar Peetam is famous for arulvakku in Tamil Nadu.[42] The people in and around Mangalore in Karnataka call the same, Buta Kola, "paathri" or "darshin"; in other parts of Karnataka, it is known by various names such as, "prashnaavali", "vaagdaana", "asei", "aashirvachana", and so on.[43][44][45][46][47] In Nepal it is known as, "Devta ka dhaamee" or "jhaakri".[48]

In English, the closest translation for these is, "oracle." The Dalai Lama, who lives in exile in northern India, still consults an oracle known as the Nechung Oracle, which is considered the official state oracle of the government of Tibet. The Dalai Lama has according to centuries-old custom, consulted the Nechung Oracle during the new year festivities of Losar.[49]

Japan

Although Japan retains a history of traditional and local methods of divination, such as onmyōdō, contemporary divination in Japan, called uranai, derives from outside sources.[50] Contemporary methods of divination in Japan include both Western and Chinese astrology, geomancy or feng shui, tarot cards, I Ching (Book of Changes) divination, and physiognomy (methods of reading the body to identify traits).[50]

In Japan, divination methods include Futomani from the Shinto tradition.[citation needed]

Personality types

Personality typing as a form of divination has been prevalent in Japan since the 1980s. Various methods exist for divining personality type. Each attempt to reveal glimpses of an individual's destiny, productive and inhibiting traits, future parenting techniques, and compatibility in marriage. Personality type is increasingly important for young Japanese, who consider personality the driving factor of compatibility, given the ongoing marriage drought and

An import to Japan, Chinese zodiac signs based on the birth year in 12 year cycles (rat, ox, tiger, hare, dragon, snake, horse, sheep, monkey, cock, dog, and boar) are frequently combined with other forms of divination, such as so-called 'celestial types' based on the planets (Saturn, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Mercury, or Uranus). Personality can also be divined using cardinal directions, the four elements (water, earth, fire, air), and yin-yang. Names can also lend important personality information under name classification which asserts that names bearing certain Japanese vowel sounds (a, i, u, e, o) share common characteristics. Numerology, which utilizes methods of divining 'birth numbers' from significant numbers such as birth date, may also reveal character traits of individuals.[51]

Individuals can also assess their own and others' personalities according to physical characteristics. Blood type remains a popular form of divination from physiology. Stemming from Western influences, body reading or ninsou, determines personality traits based on body measurements. The face is the most commonly analyzed feature, with eye size, pupil shape, mouth shape, and eyebrow shape representing the most important traits. An upturned mouth may be cheerful, and a triangle eyebrow may indicate that someone is strong-willed.[51]

Methods of assessment in daily life may include self-taken measurements or quizzes. As such, magazines targeted at women in their early-to-mid twenties feature the highest concentration of personality assessment guides. There are approximately 144 different women's magazines, known as nihon zashi koukoku kyoukai, published in Japan aimed at this audience.[51]

Japanese tarot

The adaptation of the Western divination method of tarot cards into Japanese culture presents a particularly unique example of contemporary divination as this adaptation mingles with Japan's robust visual culture. Japanese tarot cards are created by professional artists, advertisers, and fans of tarot. One tarot card collector claimed to have accumulated more than 1,500 Japan-made decks of tarot cards.

Japanese tarot cards fall into diverse categories such as:

- Inspiration Tarot (reikan tarotto);

- I-Ching Tarot (ekisen tarotto);

- Spiritual Tarot (supirichuaru tarotto);

- Western Tarot (seiyō tarotto); and

- Eastern Tarot (tōyō tarotto).

The images on tarot cards may come from images from Japanese popular culture, such as characters from manga and anime including Hello Kitty, or may feature cultural symbols. Tarot cards may adapt the images of Japanese historical figures, such as high priestess Himiko (170–248CE) or imperial court wizard Abe no Seimei (921–1005CE) . Still others may feature images of cultural displacement, such as English knights, pentagrams, the Jewish Torah, or invented glyphs. The introduction of such cards began by the 1930s and reached prominence 1970s. Japanese tarot cards were originally created by men, often based on the Rider-Waite-Smith tarot published by the Rider Company in London in 1909.[52] Since, the practice of Japanese tarot has become overwhelmingly feminine and intertwined with kawaii culture. Referring to the cuteness of tarot cards, Japanese model Kuromiya Niina was quoted as saying "because the images are cute, even holding them is enjoyable."[53] While these differences exist, Japanese tarot cards function similarly to their Western counterparts. Cards are shuffled and cut into piles then used to forecast the future, for spiritual reflection, or as a tool for self-understanding.[52]

Taiwan

A common act of divination in Taiwan is called the Poe. “The Poe” translated to English means “moon boards”. It consists of two wood or bamboo blocks cut into the shape of a crescent moon. The one edge is rounded while the other is flat; the two are mirror images. Both crescents are held out in one's palms and while kneeling, they are raised to the forehead level. Once in this position, the blocks are dropped and the future can be understood depending on their landing. If both fall flat side up or both fall rounded side up, that can be taken as a failure of the deity to agree. If the blocks land one rounded and one flat, the deity indicates "Yes", or positive. “Laughing poe” is when rounded sides land down and they rock before coming to a standstill. “Negative poe” is when the flat sides fall downward and abruptly stop; this indicates "No". When there is a positive fall, it is called “Sacred poe”, although the negative falls are not usually taken seriously. As the blocks are being dropped the question is said in a murmur, and if the answer is yes, the blocks are dropped again. To make sure the answer is definitely a yes, the blocks must fall in a “yes” position three times in a row.[citation needed]

A more serious type of divination is the Kiō-á. There is a small wooden chair, and around the sides of the chair are small pieces of wood that can move up and down in their sockets, this causes a clicking sounds when the chair is moved in any way. Two men hold this chair by its legs before an altar, while the incense is being burned, and the deity is invited to descend onto the chair. It is seen that it is in the chair by an onset of motion. Eventually, the chair crashes onto a table prepared with wood chips and burlap. The characters on the table are then traced and these are said to be written by the deity who possessed the chair, these characters are then interpreted for the devotees.[54]

Contemporary divination in Africa

Divination is widespread throughout Africa. Among many examples it is one of the central tenets of Serer religion in Senegal. Only those who have been initiated as Saltigues (the Serer high priests and priestesses) can divine the future.[55][56] These are the "hereditary rain priests"[57] whose role is both religious and medicinal.[56][57]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ "Anthropological Studies of Divination". anthropology.ac.uk.

- ^ "M. Tullius Cicero, Divination".

- ^ "Divination | Religion, History & Practices | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-10-28.

- ^ Silva (2016).

- ^ "Divination | Religion, History & Practices | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2023-10-28.

- ^ Morgan 2016, pp. 502–504.

- ^ "10 Basic Divination Methods to Try". Learn Religions. Retrieved 2023-10-28.

- ^

Sørensen, Jesper Frøkjær; Petersen, Anders Klostergaard (3 May 2021). "Manipulating the Divine - an Introduction". In Sørensen, Jesper; Petersen, Anders Klostergaard (eds.). Theoretical and Empirical Investigations of Divination and Magic: Manipulating the Divine. Volume 171 of Numen Book Series: Studies in the history of religions - ISSN 0169-8834. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV. p. 10. ISBN 9789004447585. Retrieved 9 December 2023.

- ISBN 1-57607-654-7

- ISBN 978-0-313-35507-3

- ^ "Lucian of Samosata : Alexander the False Prophet". tertullian.org.

- ISBN 978-0-19-500267-6.

- ^ Hatch, Trevan G. (2007). "Magic, Biblical Law, and the Israelite Urim and Thummim". Studia Antiqua. 5 (2) – via Scholars Archive.

- ISSN 1086-3184.

- ^ Gabbay, Uri (2016). "The Practice of Divination in the Ancient Near East". TheTorah.com. Archived from the original on April 14, 2024.

- ^ "The Seer in Ancient Greece". Princeton Classics. Retrieved 28 November 2022.

- OCLC 290580029.

- ^ Flower, Michael Attyah. The Seer in Ancient Greece. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008.

- ISBN 0-7425-3386-7

- ^ "Council of Trullo - Apostolic Confraternity Seminary". apostolicconfraternityseminary.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-07.

- ISBN 0-7425-3386-7

- ^ Ennemoser, Joseph. (1856). The History of Magic. London: Henry G. Bohn, York Street, Covent Garden. p. 59

- ^ "Wiccan Priest Fights Local Ordinance Banning Fortune Telling (Louisiana)". pluralism.org. Archived from the original on 2011-07-27. Retrieved 2009-10-06.

- ISBN 978-1-57607-243-1. Retrieved 2023-05-05.

- ^ Kuusela, Tommy (2014). "Swedish year walk: from folk tradition to computer game. In: Island Dynamics Conference on Folk Belief & Traditions of the Supernatural: Experience, Place, Ritual, & Narrative. Shetland Isles, UK, 24–30 March 2014".

- ^ a b Leoni, Lory & Gruber (2016), p. 13.

- The British Museum, 2017.

- ^ Leoni, Lory & Gruber (2016), pp. 10, 16–17.

- ^ Leoni, Lory & Gruber (2016), pp. 13, 16–17.

- ^ a b Leoni, Lory & Gruber (2016), p. 21.

- ^ Leoni, Lory & Gruber (2016), p. 26.

- ^ Leoni, Lory & Gruber (2016), pp. 26–27.

- ^ Leoni, Lory & Gruber (2016), pp. 26–31.

- ^ a b c Leoni, Lory & Gruber (2016), p. 31.

- ^ Graw (2012), pp. 19–20.

- ^ Graw (2012), p. 19.

- ^ Francis, Edgar W. "Magic and Divination in the Medieval Islamic Middle East." History Compass 9, no. 8 (2011): 624

- ^ Leoni, Lory & Gruber (2016), p. 17.

- ^ a b c Miller (2007), p. [page needed].

- ^ Sandstrom, Alan R. "Divination." In David Carrasco (ed). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures. : Oxford University Press, 2001.

- ^ "'Devakoothu'; the lone woman Theyyam in North Malabar". Mathrubhumi. Archived from the original on 2021-06-06. Retrieved 2021-11-03.

- ISBN 978-1-1375-8909-5)

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ^ Brückner, Heidrun (1987). "Bhuta Worship in Coastal Karnataka: An Oral Tulu Myth and Festival Ritual of Jumadi". Studien zur Indologie und Iranistik. 13/14: 17–37.

- ^ Brückner, Heidrun (1992). "Dhumavati-Bhuta" An Oral Tulu-Text Collected in the 19th Century. Edition, Translation, and Analysis". Studien zur Indologie und Iranistik. 13/14: 13–63.

- ^ Brückner, Heidrun (1995). Fürstliche Fest: Text und Rituale der Tuḷu-Volksreligion an der Westküste Südindiens. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. pp. 199–201.

- ^ Brückner, Heidrun (2009a). On an Auspicious Day, at Dawn … Studies in Tulu Culture and Oral Literature. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- ^ Brückner, Heidrun (2009b). "Der Gesang von der Büffelgottheit" in Wenn Masken Tanzen – Rituelles Theater und Bronzekunst aus Südindien edited by Johannes Beltz. Zürich: Rietberg Museum. pp. 57–64.

- ISBN 978-81-7835-325-8.

- ISBN 0-349-11111-1. p.233

- ^ a b Miller (2014).

- ^ a b c d Miller (1997).

- ^ a b Miller (2017).

- ^ Miller (2011).

- ^ Rohsenow, Hill Gates, and David K. Jordan. “Gods, Ghosts, and Ancestors: The Folk Religion of a Taiwanese Village.” The Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 33, no. 3, 1974, p. 478., doi:10.2307/2052956.

- ^ Sarr, Alioune, « Histoire du Sine-Saloum » (introduction, bibliographie et notes par Charles Becker), in Bulletin de l'IFAN, tome 46, série B, nos 3-4, 1986-1987 pp 31-38

- ^ ISBN 2-7384-5196-9

- ^ ISBN 978-0-520-23591-5.

Works cited

- Graw, Knut (2012). "Divination and Islam: Existential Perspectives in the Study of Ritual and Religious Praxis in Senegal and Gambia". In Schielke, Samuli; Debevec, Liza (eds.). Ordinary Lives and Grand Schemes an Anthropology of Everyday Religion. EASA Series. Vol. 18. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Greenbaum, Dorian G. (2015). The Daimon in Hellenistic Astrology: Origins and Influence. Ancient Magic and Divination. Vol. 11. LCCN 2015028673.

- Leoni, Francesca; Lory, Pierre; Gruber, Christiane (2016). Power and Protection: Islamic Art and the Supernatural. ISBN 978-1910807095.

- – via Academia.edu.

- Miller, Laura (May 2011). "Tantalizing Tarot and Cute Cartomancy in Japan". Japanese Studies. 31 (1): 73–91. S2CID 144749662.

- Miller, Laura (2014). "The divination arts in girl culture". In Kawano, Satsuki; Roberts, Glenda S.; Long, Susan Orpett (eds.). Capturing Contemporary Japan: Differentiation and Uncertainty. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. pp. 334–358 – via Academia.edu.

- Miller, Laura (2017). "Japanese Tarot Cards". ASIANetwork Exchange. 24 (1): 1–28. doi:10.16995/ane.244.

- Miller, Mary (2007). Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Silva, Sonia (2016). "Object and Objectivity in Divination". Material Religion. 12 (4): 507–509. S2CID 73665747.

- Morgan, David (2016-10-27). "Divination, Material Culture, and Chance". Material Religion. 12 (4): 502–504. ISSN 1743-2200.

Further reading

- Beerden, K. 2013. Worlds full of signs: ancient Greek divination in context. Leiden: Brill.

- Engels, D. 2007. Das römische Vorzeichenwesen (753-27 v.Chr.). Quellen, Terminologie, Kommentar, historische Entwicklung. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag.

- Evans-Pritchard, E. E. 1976. Witchcraft, oracles, and magic among the Azande.

- Fahd, Toufic. 1966. La divination arabe; études religieuses, sociologiques et folkloriques sur le milieu natif d’Islam.

- Hitti, Philip K. 1968. Makers of Arab History. Princeton, NJ. St. Martin's Press. p. 61.

- ISBN 9780870999338.

- ISBN 0-87773-214-0.

- Sahagún, Bernardino de. General History of the Things of New Spain, Book 4, The Soothsayers and Book 5, The Omens. Number 14, parts 5 and 6. Translated by Charles E. Dibble and Arthur J. O. Anderson. Santa Fe, N. M., 1979. This single volume of the Florentine Codex contains books 4 and 5, listing attributes of Aztec days signs and omens.

- Tedlock, Barbara. Time and the Highland Maya. Albuquerque, N.M., 1982. Detailed study of divination techniques using the ritual calendar among Quiché Maya in the Guatemalan Highlands.

- Vernant, J. P. 1974. Divination et rationalité. Paris: Éditions du Seuil.

- Watt, W. Montgomery. 1961. Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman. Edinburgh, UK. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–2.

External links

Definitions from Wiktionary

Definitions from Wiktionary Media from Commons

Media from Commons Quotations from Wikiquote

Quotations from Wikiquote Texts from Wikisource

Texts from Wikisource

- Greek Divination: a study of its methods and principles, William Reginald Halliday, Macmillan, 1913, 309pp - a complete scanned edition of a general treatment of Greek divination (at Google Books)

- David Zeitlyn and others on African Divination systems: Africa Divination: Mambila and others

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Divination" . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

| |||||||||||||||||

Magic and witchcraft | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Types |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Practices | |||||||||||||||||

| Objects | |||||||||||||||||

| Folklore and mythology | |||||||||||||||||

| Major historic treatises |

| ||||||||||||||||

| Persecution |

| ||||||||||||||||

| In popular culture | |||||||||||||||||

| Related | |||||||||||||||||

| History | British Traditional | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Other | |||

figures

- Gerald Gardner

- Doreen Valiente

- Alex Sanders

- Maxine Sanders

- Sybil Leek

- Dafo

- Margot Adler

- Victor Anderson

- Artemis

- Gavin Bone

- Lois Bourne

- Jack Bracelin

- Raymond Buckland

- Eddie Buczynski

- Zsuzsanna Budapest

- Charles Cardell

- Ipsita Roy Chakraverti

- Patricia Crowther

- Vivianne Crowley

- Robert Cochrane

- Scott Cunningham

- Phyllis Curott

- Cerridwen Fallingstar

- Janet Farrar

- Stewart Farrar

- Raven Grimassi

- Gavin Frost

- Yvonne Frost

- Philip Heselton

- Frederic Lamond

- Silver RavenWolf

- Starhawk

- Joseph Wilson

- Triple Goddess

- Horned God

- Green Man

- Spirit of nature

- Holly King / Oak King

- Mother goddess

concepts

and ritual

- List of Wiccan organisations

- Bricket Wood coven

- New Forest coven

- Neopagan witchcraft

- Witch-cult hypothesis

- Left-hand path and right-hand path

- Cunning folk in Britain

- European witchcraft

- Malleus Maleficarum

- Granny woman

- Cunning folk

- Magical alphabets

- Witching hour

- Witch-hunt

- Witches' Sabbath

- Flying ointment

- Museum of Witchcraft and Magic

- Witchcraft Research Association

- "Fluffy Bunny"

| Subgenres |

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Media |

| ||||||||||

| Awards | |||||||||||

| Fandom | |||||||||||

| Tropes |

| ||||||||||

| Related | |||||||||||