Erotic art

Erotic art is a broad field of the

Definition

The definition of erotic art can be subjective because it is dependent on context, as perceptions of what is erotic and what is art vary. A sculpture of a phallus in some cultures may be considered a traditional symbol of potency rather than overtly erotic. Material that is produced to illustrate sex education may be perceived by others as inappropriately erotic. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy defines erotic art as "art that is made with the intention to stimulate its target audience sexually, and that succeeds to some extent in doing so".[1]

A distinction is often made between erotic art and pornography, which also depicts scenes of sexual activity and is intended to evoke erotic arousal. Pornography is not usually considered fine art. People may draw a distinction based on the work's intent and message: erotic art would be works intended for purposes in addition to arousal, which could be appreciated as art by someone uninterested in their erotic content. US Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart wrote in 1964 that the distinction was intuitive, saying about hard-core pornography which would not be legally protected as erotic art, "I know it when I see it".[2]

Others, including philosophers Matthew Kieran[3] and Hans Maes,[4][5] have argued that no strict distinction can be made between erotic art and pornography.

Historical

Among the oldest surviving examples of erotic depictions are Paleolithic cave paintings and carvings, but many cultures have created erotic art. Artifacts have been discovered from ancient Mesopotamia depicting explicit heterosexual sex.[6][7] Glyptic art from the Sumerian Early Dynastic Period frequently shows scenes of frontal sex in the missionary position.[6] In Mesopotamian votive plaques from the early second millennium BC, the man is usually shown entering the woman from behind while she bends over, drinking beer through a straw.[6] Middle Assyrian lead votive figurines often represent the man standing and penetrating the woman as she rests on top of an altar.[6]

Scholars have traditionally interpreted all these depictions as scenes of ritual sex,[6] but they are more likely to be associated with the cult of Inanna, the goddess of sex and prostitution.[6] Many sexually explicit images were found in the temple of Inanna at Assur,[6] which also contained models of male and female sexual organs,[6] including stone phalli, which may have been worn around the neck as an amulet or used to decorate cult statues,[6] and clay models of the female vulva.[6]

Larco Museum, Lima. 300 CE

Depictions of sexual intercourse were not part of the general repertory of ancient Egyptian formal art,

The ancient

The

There is a long tradition of erotic art in Eastern cultures. In Japan, for example,

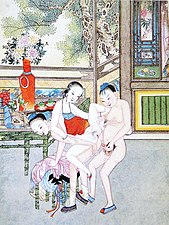

Around 1700, shunga was met with opposition and banned in Japan, but the circulation of this prominent Erotic Art continued. Shunga could be found in local libraries and homes of many Japanese citizens.[16] Similarly, the erotic art of China(known as Chungongtu) reached its popular peak during the latter part of the Ming dynasty.[17] In India, the famous Kama Sutra is an ancient sex manual that is still popularly read throughout the world.[18]

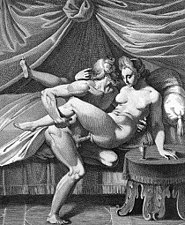

In Europe, starting with the Renaissance, there was a tradition of producing erotica for the amusement of the aristocracy. The I Modi was an erotic book with engravings of sexual scenes by Marcantonio Raimondi that were based on designs by Giulio Romano. I modi was thought to be created in around 1524 to 1527.

In 1601,

An erotic cabinet, ordered by Catherine the Great, seems to have been adjacent to her suite of rooms in the Gatchina Palace. The furniture was eccentric, with tables that had large penises for legs. Penises and vaginas were carved on the furniture and the walls were covered in erotic art. The rooms and the furniture were seen in 1941 by two Wehrmacht-officers but they seem to have vanished since then.[19][20] A documentary by Peter Woditsch suggests that the cabinet was in the Peterhof Palace and not in Gatchina.[21]

The tradition was continued by other, more modern painters, such as

By the 20th century, photography became the most common medium for erotic art. Publishers like Taschen mass-produced erotic illustrations and erotic photography.

20th century onwards

Many erotic artists worked in the 2010s. Much of the genre is still not as well accepted as the more standard genres of art such as portraiture and landscape. Erotic depictions in art went through a fundamental repositioning over the course of the 20th century. Early 20th century movements in art such as

In the mid 20th century, realism and surrealism offered new modes of representation of the nude. For surrealist artist's, the erotic became a way of exploring ideas of fantasy, the unconscious and the dream state.[23] Artist's such as Paul Delvaux, Giorgio de Chirico and Max Ernst are well-known surrealist artist's that dealt with the erotic directly. In the aftermath of the First World War, a shift away from abstracted human figures of the 1920s and 1930s towards realism took place. Artists such as British Artist Stanley Spencer led this re-appropriated approach to the human figure in Britain, with naked self-portraits of himself and his second wife in erotic settings This is explicitly evident in his work Double nude portrait, 1937.[23]

The naked portrait was arguably becoming a category of erotic art that was dominating the 20th century, just as the academic nude had dominated the 19th century.[24] Critical writings on the 'nude' and in particular the female 'nude', meant fundamental shifts in how depictions of the nude and the portrayal of sexuality were being considered. Seminal texts such as British Art historian Kenneth Clark's The nude: a study of ideal art in 1956 and Art Critic John Berger in 1972 in his book Ways of Seeing, were re-examining the notion of the naked and the nude within art. This period in art was defined by an acute engagement with the political. It marked a historical moment that stressed the importance of the sexual revolution upon art.[25]

The 1960s and 1970s were a time of social and political change across the United States and Europe. Movements included the fight for equality for women with a focus on sexuality, reproductive rights, the family, and the workplace. Artists and historians began to investigate how images in Western art and the media, were often produced within a male narrative and particularly how it perpetuated idealisations of the female subject.[26] The questioning and interrogation of the overarching male gaze within the historical art narrative, manifested in both critical writing and artistic practice, came to define much of the mid to late 20th century art and erotic art.[27] American Art Historian Carol Duncan summarises the male gaze and its relationship to erotic art, writing "More than any other theme, the nude could demonstrate that art originates in and is sustained by male erotic energy. This is why many 'seminal' works of the period are nudes."[28] Artists such as Sylvia Sleigh is an example of this reversal of the male gaze as her work depicts male sitters presented in traditional erotic reclining poses that usually were reserved for the female nude as part of the 'odalisque' tradition.[23]

The rise of feminism, the sexual revolution and conceptual art in the mid 20th century meant that the interaction between the image and audience, and the artist and audience, were beginning to be questioned and redefined, opening up new possible areas of practice. Artists began to use their own nude bodies and began to depict an alternative narrative of the erotic, through new lenses.[29] New media was beginning to be used to portray the nude and the erotic, with performance and photography being used by women artists, to draw attention to issues of gender power relations and the blurred boundaries between pornography and art.[30] Artists such as Carolee Schneemann, and Hannah Wilke were using these new mediums to interrogate the constructs of gender roles and sexuality. Wilke's photographs, for instance, satirised the mass objectification of the female body in pornography and advertising.[23]

Performance art since the 1960s has flourished and is considered as a direct response and challenge to traditional types of media and was associated with the dematerialization of the artwork or object. As performance that dealt with the erotic flourished in the 1980s and 1990s both male and female artists were exploring new strategies of representation of the erotic.[26]

Martha Edelheit was a female artist known for her contributions to erotic art as a rebellious stance against typical gender roles, which excluded women artists from participating in free sexual expression. This limited women to often be the subject of many famous Erotic Art pieces which catered to men. Edelheit was criticized for being a female artist who created erotic artwork during a time where men were main contributors in this art. Edelheit was a pioneer in the feminist art movement because she was a woman who created erotic art and also depicted herself in many of her works, which paved the way for women's equality in sexual expression.

Edelheit confronted the common stereotype that this art was pornographic by offering an alternative view of oneself. Her works paved the way for women to openly express sexual desires. Painting nude male subjects were uncommon in the 1970s; her Art turned the tables and allowed for women to be at the forefront of this fem expression revolution that occurred in the 70s.[31]

The acceptance and popularity of erotic art has pushed the genre into mainstream pop-culture and has created many famous icons.

Between 2010 and 2015

Legal standards

Whether or not an instance of erotic art is

In the United States, the 1973 ruling of the Supreme Court of the United States in Miller v. California established a three-tiered test to determine what was obscene—and thus not protected, versus what was merely erotic and thus protected by the First Amendment.

Delivering the opinion of the court, Chief Justice

The basic guidelines for the trier of fact must be: (a) whether 'the average person, applying contemporary community standards' would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest, (b) whether the work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law; and (c) whether the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.[35]

As this is still much vaguer than other judicial tests within U.S. jurisprudence, it has not reduced the conflicts that often result, especially from the ambiguities concerning what the "contemporary community standards" are. Similar difficulties in distinguishing between erotica and obscenity have been found in other legal systems.

Gallery

-

A palaeolithic, petroglyph of a vulva

-

Sex between a female and a male. Terracotta plaque. Old Babylonian Period. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul, around 2000–1500 BCE

-

Sex between a female and a male. Engraved scaraboid (gem), White chalcedony. Greco-Persian. 4th century BCE.

-

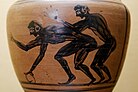

Pottery art by Brygos Painter, 480–470 BCE

-

Oinochoe by the Shuvalov Painter, around 430–420 BCE

-

Bell Krater. Ancient Greek. Late 5th to 4th century BCE

-

Inner casing of box mirror container with an engraving on a silvered surface. Ancient Greek. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Around 340–320 BCE

-

Outer casing of box mirror container with a bronze relief. Ancient Greek. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Around 340–320 BCE

-

Engraving of a sexual scene on an ancient Greek gem

-

A sleeping Hermaphrodite being viewed. Krater. Marble. Ancient Greek. 110 - 90BCE

-

Ceramic vessel. Moche, Peru. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. 300–600 CE.

-

Ceramic vessel. Pre-Columbian. Larco Museum, Lima.

-

Ceramic vessel. Pre-Columbian. Larco Museum, Lima.

-

Ceramic vessels. Pre-Columbian. Larco Museum, Lima.

-

Ceramic vessel. Pre-Columbian. Larco Museum, Lima.

-

Ceramic vessel. Pre-Columbian. Larco Museum, Lima.

-

Tantric carving from the Lakshmana Temple, Khajuraho, India

-

Frescos. Ajanta caves, 6th–7th century CE

-

Fresco. Ajanta caves. 6th–7th century CE

-

Sheela na Gigat Kilpeck, England, 12th century

-

Hôtel-de-Ville de Saint-Quentin. Saint-Quentin, France. Between 1331 to 1509

-

Masturbation. Hôtel-de-Ville de Saint-Quentin. Saint-Quentin, France. Between 1331 to 1509.

-

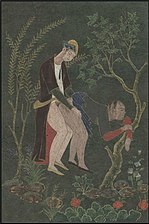

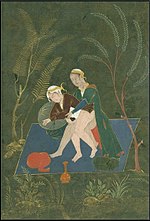

Paintings of sex being viewed in an erotic album, mid to late 18th century

-

Erotic Manuscript from Tuhfet Ul-Mulk, 1773

-

Jupiter and Juno. Jacques Joseph Coiny. 1798.

-

Spring Palace Illustration (also known as Chungongtu,春宮圖). Qing dynasty. 1636–1912.

-

Chinese Erotic Art. Gouache painting. Date of creation uncertain 1800 to 1899.

-

Hokusai, The Adonis Plant (Fukujusō), 1815

-

Hokusai, The Dream of the Fisherman's Wife, c. 1820

-

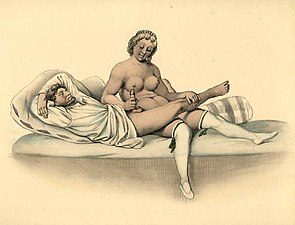

Erotic scene. Watercolour. Peter Johann Nepomuk Geiger. 1840.

-

A painting of an erotic scene behind a painting of figs and a tomato. Summonte. 1800 to 1899?

-

An erotic scene on the reverse side of the painting of figs and a tomato by Summonte. 1800 to 1899?

-

Anal sex between two males. Watercolour on paper. Around 1880 - 1926

-

Paul avril, illustration for Fanny Hill, 1907

-

Egon Schiele, untitled nude, 1914

-

Hyperrealistic sculpture of lascivious princess Europa by German sculptor Georg Viktor, 2014

See also

- Artistic freedom

- Blue Movie by Andy Warhol

- Dionysism art

- Erotic art in Pompeii and Herculaneum

- Erotic comics

- Erotic photography

- Fantastic art

- Fetish art

- Golden Age of Porn

- Hentai

- History of erotic depictions

- I Modi

- Lesbian erotica

- Nude (art)

- Pin-up model

- Pornography

- Pregnancy in art

- Sex in advertising

- Sex in film

- Sexual arousal

- Yiff

- Zazel

- Khajuraho Group of Monuments

References

- ^ Maes, Hans (1 December 2018). "Erotic Art". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University – via Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ^ Jacobellis v. Ohio, 378 U.S. 184, 197 (1964).

- S2CID 201770457.

- S2CID 170101830.

- ^ Maes, Hans. Ed. Pornographic Art and the Aesthetics of Pornography, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.[page needed]

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7141-1705-8.

- ISBN 978-0313294976.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-674-95469-4.

Turin erotic papyrus.

- ^ a b c d O'Connor, David (September–October 2001). "Eros in Egypt". Archaeology Odyssey. Archived from the original on 30 January 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-415-22366-9.

- ^ Chambers, M., Leslie, J. & Butts, S. (2005) Pornography: the Secret History of Civilization [DVD], Koch Vision.

- S2CID 162204319.

- ^ "The Archaeology of a Byzantine City - Link IV: Qusayr 'Amra". www.bijleveldbooks.nl. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-520-23665-3.

- ^ "Shunga". Japanese art net and architecture users system. 2001. Retrieved 23 August 2006.

- ^ "What is Shunga?". Artsy. 24 September 2013.

- ISBN 90-5496-039-6.

- ISBN 0-89281-525-6.[page needed]

- ^ Igorʹ Semenovich Kon and James Riordan, Sex and Russian Society page 18.

- ^ Peter Dekkers (6 December 2003). "Het Geheim van Catherina de Grote" [The Secret of Catherine the Great]. Trouw (in Dutch).

- ^ Woditsch, Peter. "The Secret of Catherine the Great". De Productie. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2014. Includes trailer of the documentary by Peter Woditsch.

- )

- ^ )

- )

- )

- ^ a b "investigating identity". Museum of Modern Art.

- JSTOR 1358010.

- OCLC 1028731181.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link - )

- S2CID 55834856.

- S2CID 191577484.

- ISBN 0-88184-970-7

- ^ Alyssa Buffenstein (25 March 2016). "One Sexologist's Quest to Stimulate Las Vegas' Art Scene". The Creators Project.

- OCLC 317919538.

- ^ Miller v. California, 413 U.S. 15, 24 (1973).

External links

- 10 Best Erotic Works of Art, The Guardian

- Erotic Art, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Erótica graphical history, The nude in art history. (Spanish)

- Erotic Art – Shunga Gallery - Artistic and Intellectual Presentations.

- Honesterotica.com, Erotic illustration from late Victorian to the present day.