First Amendment to the United States Constitution

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Constitution of the United States |

|---|

|

| Preamble and Articles |

|

Amendments to the Constitution |

|

Unratified Amendments : |

| History |

| Full text |

The First Amendment (Amendment I) to the

The Bill of Rights was proposed to assuage Anti-Federalist opposition to Constitutional ratification. Initially, the First Amendment applied only to laws enacted by the Congress, and many of its provisions were interpreted more narrowly than they are today. Beginning with Gitlow v. New York (1925), the Supreme Court applied the First Amendment to states—a process known as incorporation—through the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

In

The Free Press Clause protects publication of information and opinions, and applies to a wide variety of media. In

Although the First Amendment applies only to

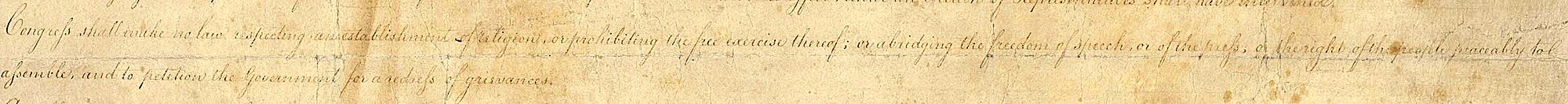

Text

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.[4]

Background

The right to petition for redress of grievances was a principle included in the 1215 Magna Carta, as well as the 1689 English Bill of Rights. In 1776, the second year of the American Revolutionary War, the Virginia colonial legislature passed a Declaration of Rights that included the sentence "The freedom of the press is one of the greatest bulwarks of liberty, and can never be restrained but by despotic Governments." Eight of the other twelve states made similar pledges. However, these declarations were generally considered "mere admonitions to state legislatures", rather than enforceable provisions.[5]

After several years of comparatively weak government under the Articles of Confederation, a Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia proposed a new constitution on September 17, 1787, featuring among other changes a stronger chief executive. George Mason, a Constitutional Convention delegate and the drafter of Virginia's Declaration of Rights, proposed that the Constitution include a bill of rights listing and guaranteeing civil liberties. Other delegates—including future Bill of Rights drafter James Madison—disagreed, arguing that existing state guarantees of civil liberties were sufficient and any attempt to enumerate individual rights risked the implication that other, unnamed rights were unprotected. After a brief debate, Mason's proposal was defeated by a unanimous vote of the state delegations.[6]

For the constitution to be ratified, however, nine of the thirteen states were required to approve it in state conventions. Opposition to ratification ("Anti-Federalism") was partly based on the Constitution's lack of adequate guarantees for civil liberties. Supporters of the Constitution in states where popular sentiment was against ratification (including Virginia, Massachusetts, and New York) successfully proposed that their state conventions both ratify the Constitution and call for the addition of a bill of rights. The U.S. Constitution was eventually ratified by all thirteen states. In the 1st United States Congress, following the state legislatures' request, James Madison proposed twenty constitutional amendments, and his proposed draft of the First Amendment read as follows:

The civil rights of none shall be abridged on account of religious belief or worship, nor shall any national religion be established, nor shall the full and equal rights of conscience be in any manner, or on any pretext, infringed. The people shall not be deprived or abridged of their right to speak, to write, or to publish their sentiments; and the freedom of the press, as one of the great bulwarks of liberty, shall be inviolable. The people shall not be restrained from peaceably assembling and consulting for their common good; nor from applying to the Legislature by petitions, or remonstrances, for redress of their grievances.[7]

This language was greatly condensed by Congress, and passed the House and Senate with almost no recorded debate, complicating future discussion of the Amendment's intent.[8][9] Congress approved and submitted to the states for their ratification twelve articles of amendment on September 25, 1789. The revised text of the third article became the First Amendment, because the last ten articles of the submitted 12 articles were ratified by the requisite number of states on December 15, 1791, and are now known collectively as the Bill of Rights.[10][11]

Freedom of religion

Religious liberty, also known as freedom of religion, is "the right of all persons to believe, speak, and act – individually and in community with others, in private and in public – in accord with their understanding of ultimate truth."

Plainly, a community may not suppress, or the state tax, the dissemination of views because they are unpopular, annoying or distasteful. If that device were ever sanctioned, there would have been forged a ready instrument for the suppression of the faith which any minority cherishes but which does not happen to be in favor. That would be a complete repudiation of the philosophy of the Bill of Rights.[18]

In his dissenting opinion in McGowan v. Maryland (1961), Justice William O. Douglas illustrated the broad protections offered by the First Amendment's religious liberty clauses:

The First Amendment commands government to have no interest in theology or ritual; it admonishes government to be interested in allowing religious freedom to flourish—whether the result is to produce

Protestants, or to turn the people toward the path of Buddha, or to end in a predominantly Moslem nation, or to produce in the long run atheists or agnostics. On matters of this kind, government must be neutral. This freedom plainly includes freedom from religion, with the right to believe, speak, write, publish and advocate anti-religious programs. Board of Education v. Barnette, supra, 319 U. S. 641. Certainly the "free exercise" clause does not require that everyone embrace the theology of some church or of some faith, or observe the religious practices of any majority or minority sect. The First Amendment, by its "establishment" clause, prevents, of course, the selection by government of an "official" church. Yet the ban plainly extends farther than that. We said in Everson v. Board of Education, 330 U. S. 1, 330 U. S. 16, that it would be an "establishment" of a religion if the Government financed one church or several churches. For what better way to "establish" an institution than to find the fund that will support it? The "establishment" clause protects citizens also against any law which selects any religious custom, practice, or ritual, puts the force of government behind it, and fines, imprisons, or otherwise penalizes a person for not observing it. The Government plainly could not join forces with one religious group and decree a universal and symbolic circumcision. Nor could it require all children to be baptized or give tax exemptions only to those whose children were baptized.[19]

Those who would renegotiate the boundaries between church and state must therefore answer a difficult question: Why would we trade a system that has served us so well for one that has served others so poorly?

--

The First Amendment tolerates neither governmentally established religion nor governmental interference with religion.[21] One of the central purposes of the First Amendment, the Supreme Court wrote in Gillette v. United States (1970), consists "of ensuring governmental neutrality in matters of religion."[22] The history of the Establishment Clause and the Free Exercise Clause and the Supreme Court's own constitutional jurisprudence with respect to these clauses was explained in the 1985 case Wallace v. Jaffree.[23] The Supreme Court noted at the outset that the First Amendment limits equally the power of Congress and of the states to abridge the individual freedoms it protects. The First Amendment was adopted to curtail the power of Congress to interfere with the individual's freedom to believe, to worship, and to express himself in accordance with the dictates of his own conscience. The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment imposes on the states the same limitations the First Amendment had always imposed on the Congress.[24] This "elementary proposition of law" was confirmed and endorsed time and time again in cases like Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296, 303 (1940)[b] and Wooley v. Maynard (1977).[c][27] The central liberty that unifies the various clauses in the First Amendment is the individual's freedom of conscience:[28]

Just as the right to speak and the right to refrain from speaking are complementary components of a broader concept of individual freedom of mind, so also the individual's freedom to choose his own creed is the counterpart of his right to refrain from accepting the creed established by the majority. At one time, it was thought that this right merely proscribed the preference of one Christian

adherent of a non-Christian faith such as Islam or Judaism. But when the underlying principle has been examined in the crucible of litigation, the Court has unambiguously concluded that the individual freedom of conscience protected by the First Amendment embraces the right to select any religious faith or none at all. This conclusion derives support not only from the interest in respecting the individual's freedom of conscience, but also from the conviction that religious beliefs worthy of respect are the product of free and voluntary choice by the faithful, and from recognition of the fact that the political interest in forestalling intolerance extends beyond intolerance among Christian sects – or even intolerance among "religions" – to encompass intolerance of the disbeliever and the uncertain.[29]

Establishment of religion

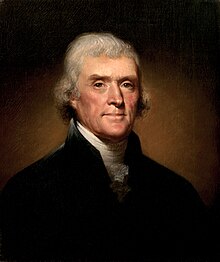

The precise meaning of the Establishment Clause can be traced back to the beginning of the 19th century. Thomas Jefferson wrote about the First Amendment and its restriction on Congress in an 1802 reply to the Danbury Baptists,[30] a religious minority that was concerned about the dominant position of the Congregational church in Connecticut, who had written to the newly elected president about their concerns. Jefferson wrote back:

Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between Man & his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legitimate powers of government reach actions only, and not opinions, I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should "make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof", thus building a wall of separation between Church & State. Adhering to this expression of the supreme will of the nation in behalf of the rights of conscience, I shall see with sincere satisfaction the progress of those sentiments which tend to restore to man all his natural rights, convinced he has no natural right in opposition to his social duties.[31]

In Reynolds v. United States (1878) the Supreme Court used these words to declare that "it may be accepted almost as an authoritative declaration of the scope and effect of the amendment thus secured. Congress was deprived of all legislative power over mere [religious] opinion, but was left free to reach [only those religious] actions which were in violation of social duties or subversive of good order." Quoting from Jefferson's Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom the court stated further in Reynolds:

In the preamble of this act ... religious freedom is defined; and after a recital 'that to suffer the civil magistrate to intrude his powers into the field of opinion, and to restrain the profession or propagation of principles on supposition of their ill tendency, is a dangerous fallacy which at once destroys all religious liberty,' it is declared 'that it is time enough for the rightful purposes of civil government for its officers to interfere [only] when [religious] principles break out into overt acts against peace and good order.' In these two sentences is found the true distinction between what properly belongs to the church and what to the State.

Reynolds was the first Supreme Court decision to use the metaphor "a wall of separation between Church and State." American historian George Bancroft was consulted by Chief Justice Morrison Waite in Reynolds regarding the views on establishment by the Founding Fathers. Bancroft advised Waite to consult Jefferson and Waite then discovered the above quoted letter in a library after skimming through the index to Jefferson's collected works according to historian Don Drakeman.[32]

The Establishment Clause[33] forbids federal, state, and local laws which purpose is "an establishment of religion." The term "establishment" denoted in general direct aid to the church by the government.[34] In Larkin v. Grendel's Den, Inc. (1982) the Supreme Court stated that "the core rationale underlying the Establishment Clause is preventing "a fusion of governmental and religious functions," Abington School District v. Schempp, 374 U. S. 203, 374 U. S. 222 (1963)."[35] The Establishment Clause acts as a double security, for its aim is as well the prevention of religious control over government as the prevention of political control over religion.[14] The First Amendment's framers knew that intertwining government with religion could lead to bloodshed or oppression, because this happened too often historically. To prevent this dangerous development they set up the Establishment Clause as a line of demarcation between the functions and operations of the institutions of religion and government in society.[36] The Federal government of the United States as well as the state governments are prohibited from establishing or sponsoring religion,[14] because, as observed by the Supreme Court in Walz v. Tax Commission of the City of New York (1970), the 'establishment' of a religion historically implied sponsorship, financial support, and active involvement of the sovereign in religious activity.[37] The Establishment Clause thus serves to ensure laws, as said by Supreme Court in Gillette v. United States (1970), which are "secular in purpose, evenhanded in operation, and neutral in primary impact".[22]

The First Amendment's prohibition on an establishment of religion includes many things from prayer in widely varying government settings over financial aid for religious individuals and institutions to comment on religious questions.[15] The Supreme Court stated in this context: "In these varied settings, issues of about interpreting inexact Establishment Clause language, like difficult interpretative issues generally, arise from the tension of competing values, each constitutionally respectable, but none open to realization to the logical limit."[15] The National Constitution Center observes that, absent some common interpretations by jurists, the precise meaning of the Establishment Clause is unclear and that decisions by the United Supreme Court relating to the Establishment Clause often are by 5–4 votes.[38] The Establishment Clause, however, reflects a widely held consensus that there should be no nationally established church after the American Revolutionary War.[38] Against this background the National Constitution Center states:

Virtually all jurists agree that it would violate the Establishment Clause for the government to compel attendance or financial support of a religious institution as such, for the government to interfere with a religious organization's selection of clergy or religious doctrine; for religious organizations or figures acting in a religious capacity to exercise governmental power; or for the government to extend benefits to some religious entities and not others without adequate secular justification.[38]

Originally, the First Amendment applied only to the federal government, and some states continued official state religions after ratification. Massachusetts, for example, was officially Congregational until the 1830s.[39] In Everson v. Board of Education (1947), the Supreme Court incorporated the Establishment Clause (i.e., made it apply against the states):

The 'establishment of religion' clause of the First Amendment means at least this: Neither a state nor the Federal Government can set up a church. Neither can pass laws which aid one religion, aid all religions, or prefer one religion to another ... in the words of Jefferson, the [First Amendment] clause against establishment of religion by law was intended to erect 'a wall of separation between church and State'. ... That wall must be kept high and impregnable. We could not approve the slightest breach.[40]

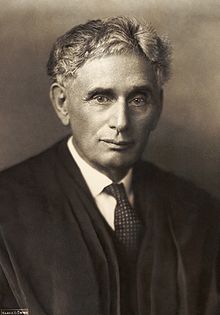

Citing Justice Hugo Black in Torcaso v. Watkins (1961) the Supreme Court repeated its statement from Everson v. Board of Education (1947) in Abington School District v. Schempp (1963):

We repeat and again reaffirm that neither a State nor the Federal Government can constitutionally force a person 'to profess a belief or disbelief in any religion.' Neither can it constitutionally pass laws or impose requirements which aid all religions as against non-believers, and neither can it aid those religions based on a belief in the existence of God as against those religions founded on different beliefs.[42]

At the core of the Establishment Clause lays the core principle of denominational neutrality.[43] In Epperson v. Arkansas (1968) the Supreme Court outlined the broad principle of denominational neutrality mandated by the First Amendment: "Government in our democracy, state and national, must be neutral in matters of religious theory, doctrine, and practice. It may not be hostile to any religion or to the advocacy of no-religion, and it may not aid, foster, or promote one religion or religious theory against another or even against the militant opposite. The First Amendment mandates governmental neutrality between religion and religion, and between religion and nonreligion."[44] The clearest command of the Establishment Clause is, according to the Supreme Court in Larson v. Valente, 456 U.S. 228 (1982), that one religious denomination cannot be officially preferred over another.[45] In Zorach v. Clauson (1952) the Supreme Court further observed: "Government may not finance religious groups nor undertake religious instruction nor blend secular and sectarian education nor use secular institutions to force one or some religion on any person. But we find no constitutional requirement which makes it necessary for government to be hostile to religion and to throw its weight against efforts to widen the effective scope of religious influence. The government must be neutral when it comes to competition between sects. It may not thrust any sect on any person. It may not make a religious observance compulsory. It may not coerce anyone to attend church, to observe a religious holiday, or to take religious instruction. But it can close its doors or suspend its operations as to those who want to repair to their religious sanctuary for worship or instruction."[46] In McCreary County v. American Civil Liberties Union (2005) the Court explained that when the government acts with the ostensible and predominant purpose of advancing religion, then it violates that central Establishment Clause value of official religious neutrality, because there being no neutrality when the government's ostensible object is to take sides.[47]

In —the Court considered the issue of religious monuments on federal lands without reaching a majority reasoning on the subject.

Separationists

Everson used the metaphor of a wall of

In Everson, the Court adopted Jefferson's words.[53] The Court has affirmed it often, with majority, but not unanimous, support. Warren Nord, in Does God Make a Difference?, characterized the general tendency of the dissents as a weaker reading of the First Amendment; the dissents tend to be "less concerned about the dangers of establishment and less concerned to protect free exercise rights, particularly of religious minorities".[56]

Beginning with Everson, which permitted New Jersey school boards to pay for transportation to parochial schools, the Court has used various tests to determine when the wall of separation has been breached. Everson laid down the test that establishment existed when aid was given to religion, but that the transportation was justifiable because the benefit to the children was more important.

Felix Frankfurter called in his concurrence opinion in McCollum v. Board of Education (1948) for a strict separation between state and church: "Separation means separation, not something less. Jefferson's metaphor in describing the relation between Church and State speaks of a 'wall of separation', not of a fine line easily overstepped. ... 'The great American principle of eternal separation'—Elihu Root's phrase bears repetition—is one of the vital reliances of our Constitutional system for assuring unities among our people stronger than our diversities. It is the Court's duty to enforce this principle in its full integrity."[57]

In the school prayer cases of the early 1960s Engel v. Vitale and Abington School District v. Schempp, aid seemed irrelevant. The Court ruled on the basis that a legitimate action both served a secular purpose and did not primarily assist religion.

In Walz v. Tax Commission of the City of New York (1970), the Court ruled that a legitimate action could not entangle government with religion. In Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971), these points were combined into the Lemon test, declaring that an action was an establishment if:[58]

- the statute (or practice) lacked a secular purpose;

- its principal or primary effect advanced or inhibited religion; or

- it fostered an excessive government entanglement with religion.

The Lemon test has been criticized by justices and legal scholars, but it has remained the predominant means by which the Court enforced the Establishment Clause.

In Lemon, the Court stated that the separation of church and state could never be absolute: "Our prior holdings do not call for total separation between church and state; total separation is not possible in an absolute sense. Some relationship between government and religious organizations is inevitable", the court wrote. "Judicial caveats against entanglement must recognize that the line of separation, far from being a 'wall', is a blurred, indistinct, and variable barrier depending on all the circumstances of a particular relationship."[62]

After the Supreme Court ruling in the coach praying case of Kennedy v. Bremerton School District (2022), the Lemon Test may have been replaced or complemented with a reference to historical practices and understandings.[63][64][65]

Accommodationists

David Shultz has said that accommodationists claim the Lemon test should be applied selectively.

Free exercise of religion

The acknowledgement of religious freedom as the first right protected in the Bill of Rights points toward the American founders' understanding of the importance of religion to human, social, and political flourishing. The First Amendment makes clear that it sought to protect "the free exercise" of religion, or what might be called "free exercise equality."[13] Free exercise is the liberty of persons to reach, hold, practice and change beliefs freely according to the dictates of conscience. The Free Exercise Clause prohibits governmental interference with religious belief and, within limits, religious practice.[14] "Freedom of religion means freedom to hold an opinion or belief, but not to take action in violation of social duties or subversive to good order."[74] The clause withdraws from legislative power, state and federal, the exertion of any restraint on the free exercise of religion. Its purpose is to secure religious liberty in the individual by prohibiting any invasions thereof by civil authority.[75] "The door of the Free Exercise Clause stands tightly closed against any governmental regulation of religious beliefs as such, Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296, 310 U. S. 303. Government may neither compel affirmation of a repugnant belief, Torcaso v. Watkins, 367 U. S. 488; nor penalize or discriminate against individuals or groups because they hold religious views abhorrent to the authorities, Fowler v. Rhode Island, 345 U. S. 67; nor employ the taxing power to inhibit the dissemination of particular religious views, Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 319 U. S. 105; Follett v. McCormick, 321 U. S. 573; cf. Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U. S. 233."[76]

The Free Exercise Clause offers a double protection, for it is a shield not only against outright prohibitions with respect to the free exercise of religion, but also against penalties on the free exercise of religion and against indirect governmental coercion.[77] Relying on Employment Division v. Smith (1990)[78] and quoting from Church of the Lukumi Babalu Aye, Inc. v. Hialeah (1993)[79] the Supreme Court stated in Trinity Lutheran Church of Columbia, Inc. v. Comer (2017) that religious observers are protected against unequal treatment by virtue of the Free Exercise Clause and laws which target the religious for "special disabilities" based on their "religious status" must be covered by the application of strict scrutiny.[80]

In

In Cantwell v. Connecticut (1940), the Court held that the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment applied the Free Exercise Clause to the states. While the right to have religious beliefs is absolute, the freedom to act on such beliefs is not absolute.[83] Religious freedom is a universal right of all human beings and all religions, providing for the free exercise of religion or free exercise equality. Due to its nature as fundamental to the American founding and to the ordering of human society, it is rightly seen as a capricious right, i.e. universal, broad, and deep—though not absolute.[13] Justice Field put it clearly in Davis v. Beason (1890): "However free the exercise of religion may be, it must be subordinate to the criminal laws of the country, passed with reference to actions regarded by general consent as properly the subjects of punitive legislation."[84] Furthermore, the Supreme Court in Employment Division v. Smith made clear that "the right of free exercise does not relieve an individual of the obligation to comply with a "valid and neutral law of general applicability on the ground that the law proscribes (or prescribes) conduct that his religion prescribes (or proscribes)." United States v. Lee, 455 U. S. 252, 455 U. S. 263, n. 3 (1982) (STEVENS, J., concurring in judgment); see Minersville School Dist. Bd. of Educ. v. Gobitis, supra, 310 U.S. at 310 U. S. 595 (collecting cases)."[f][86][16] Smith also set the precedent[87] "that laws affecting certain religious practices do not violate the right to free exercise of religion as long as the laws are neutral, generally applicable, and not motivated by animus to religion."[88]

To accept any creed or the practice of any form of worship cannot be compelled by laws, because, as stated by the Supreme Court in Braunfeld v. Brown (1961), the freedom to hold religious beliefs and opinions is absolute.[89] Federal or state legislation cannot therefore make it a crime to hold any religious belief or opinion due to the Free Exercise Clause.[89] Legislation by the United States or any constituent state of the United States which forces anyone to embrace any religious belief or to say or believe anything in conflict with his religious tenets is also barred by the Free Exercise Clause.[89] Against this background, the Supreme Court stated that Free Exercise Clause broadly protects religious beliefs and opinions:

The free exercise of religion means, first and foremost, the right to believe and profess whatever religious doctrine one desires. Thus, the First Amendment obviously excludes all "governmental regulation of religious beliefs as such."

Serbian Eastern Orthodox Diocese v. Milivojevich, 426 U. S. 696, 426 U. S. 708–725 (1976). But the "exercise of religion" often involves not only belief and profession but the performance of (or abstention from) physical acts: assembling with others for a worship service, participating in sacramental use of bread and wine, proselytizing, abstaining from certain foods or certain modes of transportation. It would be true, we think (though no case of ours has involved the point), that a state would be "prohibiting the free exercise [of religion]" if it sought to ban such acts or abstentions only when they are engaged in for religious reasons, or only because of the religious belief that they display. It would doubtless be unconstitutional, for example, to ban the casting of "statues that are to be used for worship purposes," or to prohibit bowing down before a golden calf."[90]

In Sherbert v. Verner (1963),[91] the Supreme Court required states to meet the "strict scrutiny" standard when refusing to accommodate religiously motivated conduct. This meant the government needed to have a "compelling interest" regarding such a refusal. The case involved Adele Sherbert, who was denied unemployment benefits by South Carolina because she refused to work on Saturdays, something forbidden by her Seventh-day Adventist faith.[92] In Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972), the Court ruled that a law which "unduly burdens the practice of religion" without a compelling interest, even though it might be "neutral on its face", would be unconstitutional.[93][94]

The need for a compelling governmental interest was narrowed in

In 1993, the Congress passed the

RFRA secures Congress’ view of the right to free exercise under the First Amendment, and it provides a remedy to redress violations of that right.[109] The Supreme Court decided in light of this in Tanzin v. Tanvir (2020) that the Religious Freedom Restoration Act's express remedies provision permits litigants, when appropriate, to obtain money damages against federal officials in their individual capacities.[110] This decision is significant "not only for the plaintiffs but also for cases involving violations of religious rights more broadly."[111] In the 1982 U.S. Supreme Court case United States v. Lee (1982) (1982) the Court declared: "Congress and the courts have been sensitive to the needs flowing from the Free Exercise Clause, but every person cannot be shielded from all the burdens incident to exercising every aspect of the right to practice religious beliefs. When followers of a particular sect enter into commercial activity as a matter of choice, the limits they accept on their own conduct as a matter of conscience and faith are not to be superimposed on the statutory schemes which are binding on others in that activity."[112][113] The Supreme Court in Estate of Thornton v. Caldor, Inc. (1985) echoed this statement by quoting Judge Learned Hand from his 1953 case Otten v. Baltimore & Ohio R. Co., 205 F.2d 58, 61 (CA2 1953): "The First Amendment ... gives no one the right to insist that, in pursuit of their own interests others must conform their conduct to his own religious necessities."[114] In Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. (2014) the Supreme Court had to decide, with a view to the First Amendment's Free Exercise Clause and the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act, "the profound cultural question of whether a private, profit-making business organized as a corporation can "exercise" religion and, if it can, how far that is protected from government interference."[115] The Court decided that closely held, for-profit corporations have free exercise rights under the RFRA,[116] but its decision was not based on the constitutional protections of the First Amendment.[117]

In

Freedom of speech and of the press

The First Amendment broadly protects the rights of free speech and free press.[125] Free speech means the free and public expression of opinions without censorship, interference, or restraint by the government.[126][127][128][129] The term "freedom of speech" embedded in the First Amendment encompasses the decision what to say as well as what not to say.[130] The speech covered by the First Amendment covers many ways of expression and therefore protects what people say as well as how they express themselves.[131] Free press means the right of individuals to express themselves through publication and dissemination of information, ideas, and opinions without interference, constraint, or prosecution by the government.[132][133] In Murdock v. Pennsylvania (1943), the Supreme Court stated that "Freedom of press, freedom of speech, freedom of religion are in a preferred position.".[134] The Court added that a community may not suppress, or the state tax, the dissemination of views because they are unpopular, annoying, or distasteful. That would be a complete repudiation of the philosophy of the Bill of Rights, according to the Court.[135] In Stanley v. Georgia (1969), the Supreme Court stated that the First Amendment protects the right to receive information and ideas, regardless of their social worth, and to be generally free from governmental intrusions into one's privacy and control of one's own thoughts.[136]

The Supreme Court of the United States characterized the rights of free speech and free press as fundamental personal rights and liberties and noted that the exercise of these rights lies at the foundation of free government by free men.[137][138] The Supreme Court stated in Thornhill v. Alabama (1940) that the freedom of speech and of the press guaranteed by the United States Constitution embraces at the least the liberty to discuss publicly and truthfully all matters of public concern, without previous restraint or fear of subsequent punishment.[139] In Bond v. Floyd (1966), a case involving the Constitutional shield around the speech of elected officials, the Supreme Court declared that the First Amendment central commitment is that, in the words of New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), "debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open."[140] The Court further explained that just as erroneous statements must be protected to give freedom of expression the breathing space it needs to survive, so statements criticizing public policy and the implementation of it must be similarly protected.[140] The Supreme Court in Chicago Police Dept. v. Mosley (1972) said:

"But, above all else, the First Amendment means that government has no power to restrict expression because of its message, its ideas, its subject matter, or its content. ... To permit the continued building of our politics and culture, and to assure self-fulfillment for each individual, our people are guaranteed the right to express any thought, free from government censorship. The essence of this forbidden censorship is content control. Any restriction on expressive activity because of its content would completely undercut the "profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited, robust, and wide-open.""[125]

The level of protections with respect to free speech and free press given by the First Amendment is not limitless. As stated in his concurrence in Chicago Police Dept. v. Mosley (1972), Chief Justice Warren E. Burger said:

"Numerous holdings of this Court attest to the fact that the First Amendment does not literally mean that we "are guaranteed the right to express any thought, free from government censorship." This statement is subject to some qualifications, as for example those of Roth v. United States, 354 U. S. 476 (1957); Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire, 315 U. S. 568 (1942). See also New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U. S. 254 (1964)."[141]

Attached to the core rights of free speech and free press are several peripheral rights that make these core rights more secure. The peripheral rights encompass not only freedom of association, including privacy in one's associations, but also, in the words of Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), "the freedom of the entire university community", i.e., the right to distribute, the right to receive, and the right to read, as well as freedom of inquiry, freedom of thought, and freedom to teach.[142] The United States Constitution protects, according to the Supreme Court in Stanley v. Georgia (1969), the right to receive information and ideas, regardless of their social worth, and to be generally free from governmental intrusions into one's privacy and control of one's thoughts.[143] As stated by the Court in Stanley: "If the First Amendment means anything, it means that a State has no business telling a man, sitting alone in his own house, what books he may read or what films he may watch. Our whole constitutional heritage rebels at the thought of giving government the power to control men's minds."[144]

Wording of the clause

The First Amendment bars Congress from "abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press". U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens commented about this phraseology in a 1993 journal article: "I emphasize the word 'the' in the term 'the freedom of speech' because the definite article suggests that the draftsmen intended to immunize a previously identified category or subset of speech." Stevens said that, otherwise, the clause might absurdly immunize things like false testimony under oath.[145] Like Stevens, journalist Anthony Lewis wrote: "The word 'the' can be read to mean what was understood at the time to be included in the concept of free speech."[146] But what was understood at the time is not 100% clear.[147] In the late 1790s, the lead author of the speech and press clauses, James Madison, argued against narrowing this freedom to what had existed under English common law:

The practice in America must be entitled to much more respect. In every state, probably, in the Union, the press has exerted a freedom in canvassing the merits and measures of public men, of every description, which has not been confined to the strict limits of the common law.[148]

Madison wrote this in 1799, when he was in a dispute about the constitutionality of the

Speech critical of the government

The Supreme Court declined to rule on the

World War I

During the patriotic fervor of World War I and the First Red Scare, the Espionage Act of 1917 imposed a maximum sentence of twenty years for anyone who caused or attempted to cause "insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, or refusal of duty in the military or naval forces of the United States". Specifically, the Espionage Act of 1917 states that if anyone allows any enemies to enter or fly over the United States and obtain information from a place connected with the national defense, they will be punished.[155] Hundreds of prosecutions followed.[156] In 1919, the Supreme Court heard four appeals resulting from these cases: Schenck v. United States, Debs v. United States, Frohwerk v. United States, and Abrams v. United States.[157]

In the first of these cases,

In Debs v. United States, the Court elaborated on the "clear and present danger" test established in Schenck.[163] On June 16, 1918, Eugene V. Debs, a political activist, delivered a speech in Canton, Ohio, in which he spoke of "most loyal comrades were paying the penalty to the working class—these being Wagenknecht, Baker and Ruthenberg, who had been convicted of aiding and abetting another in failing to register for the draft."[164] Following his speech, Debs was charged and convicted under the Espionage Act. In upholding his conviction, the Court reasoned that although he had not spoken any words that posed a "clear and present danger", taken in context, the speech had a "natural tendency and a probable effect to obstruct the recruiting services".[165][166] In Abrams v. United States, four Russian refugees appealed their conviction for throwing leaflets from a building in New York; the leaflets argued against President Woodrow Wilson's intervention in Russia against the October Revolution. The majority upheld their conviction, but Holmes and Justice Louis Brandeis dissented, holding that the government had demonstrated no "clear and present danger" in the four's political advocacy.[161]

Extending protections

The Supreme Court denied a number of Free Speech Clause claims throughout the 1920s, including the appeal of a labor organizer, Benjamin Gitlow, who had been convicted after distributing a manifesto calling for a "revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat".

Those who won our independence ... believed that freedom to think as you will and to speak as you think are means indispensable to the discovery and spread of political truth; that without free speech and assembly discussion would be futile; that with them, discussion affords ordinarily adequate protection against the dissemination of noxious doctrine; that the greatest menace to freedom is an inert people; that public discussion is a political duty; and that this should be a fundamental principle of the American government.[171]

In

Although the Court referred to the clear and present danger test in a few decisions following Thornhill,

The demands of free speech in a democratic society as well as the interest in national security are better served by candid and informed weighing of the competing interests, within the confines of the judicial process.[183]

In Yates v. United States (1957), the Supreme Court limited the Smith Act prosecutions to "advocacy of action" rather than "advocacy in the realm of ideas". Advocacy of abstract doctrine remained protected while speech explicitly inciting the forcible overthrow of the government was punishable under the Smith Act.[186][187]

During the

[Our] decisions have fashioned the principle that the constitutional guarantees of free speech and free press do not allow a State to forbid or proscribe advocacy of the use of force or law violation except where such advocacy is directed to inciting or producing imminent lawless action and is likely to incite or cause such action.[195]

In Cohen v. California (1971),[196] the Court voted reversed the conviction of a man wearing a jacket reading "Fuck the Draft" in the corridors of a Los Angeles County courthouse. Justice John Marshall Harlan II wrote in the majority opinion that Cohen's jacket fell in the category of protected political speech despite the use of an expletive: "One man's vulgarity is another man's lyric."[197]

Political speech

The ability to publicly criticize even the most prominent politicians and leaders without fear of retaliation is part of the First Amendment, because political speech is core First Amendment speech. As the Supreme Court stated with respect to the judicial branch of the government exemplarily that the First Amendment prohibits "any law abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press ... It must be taken as a command of the broadest scope that explicit language, read in the context of a liberty-loving society, will allow. [...] The assumption that respect for the judiciary can be won by shielding judges from published criticism wrongly appraises the character of American public opinion. For it is a prized American privilege to speak one's mind, although not always with perfect good taste, on all public institutions. And an enforced silence, however limited, solely in the name of preserving the dignity of the bench would probably engender resentment, suspicion, and contempt much more than it would enhance respect."[198]

Anonymous speech

In Talley v. California (1960),[199] the Court struck down a Los Angeles city ordinance that made it a crime to distribute anonymous pamphlets. Justice Hugo Black wrote in the majority opinion: "There can be no doubt that such an identification requirement would tend to restrict freedom to distribute information and thereby freedom of expression. ... Anonymous pamphlets, leaflets, brochures and even books have played an important role in the progress of mankind."[200] In McIntyre v. Ohio Elections Commission (1995),[201] the Court struck down an Ohio statute that made it a crime to distribute anonymous campaign literature.[202] However, in Meese v. Keene (1987),[203] the Court upheld the Foreign Agents Registration Act of 1938, under which several Canadian films were defined as "political propaganda", requiring their sponsors to be identified.[204]

Campaign finance

In Buckley v. Valeo (1976),[205] the Supreme Court reviewed the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971 and related laws, which restricted the monetary contributions that may be made to political campaigns and expenditure by candidates. The Court affirmed the constitutionality of limits on campaign contributions, saying they "serve[d] the basic governmental interest in safeguarding the integrity of the electoral process without directly impinging upon the rights of individual citizens and candidates to engage in political debate and discussion."[206] However, the Court overturned the spending limits, which it found imposed "substantial restraints on the quantity of political speech".[207][208]

The court again scrutinized campaign finance regulation in

In

In

In

Flag desecration

The divisive issue of flag desecration as a form of protest first came before the Supreme Court in Street v. New York (1969).[220] In response to hearing an erroneous report of the murder of civil rights activist James Meredith, Sidney Street burned a 48-star U.S. flag. Street was arrested and charged with a New York state law making it a crime "publicly [to] mutilate, deface, defile, or defy, trample upon, or cast contempt upon either by words or act [any flag of the United States]".[221] The Court, relying on Stromberg v. California (1931),[222] found that because the provision of the New York law criminalizing "words" against the flag was unconstitutional, and the trial did not sufficiently demonstrate he had been convicted solely under the provisions not yet deemed unconstitutional, the conviction was unconstitutional. The Court, however, "resist[ed] the pulls to decide the constitutional issues involved in this case on a broader basis" and left the constitutionality of flag-burning unaddressed.[223][224]

The ambiguity with regard to flag-burning statutes was eliminated in Texas v. Johnson (1989).[225] In that case, Gregory Lee Johnson burned an American flag at a demonstration during the 1984 Republican National Convention in Dallas, Texas. Charged with violating a Texas law prohibiting the vandalizing of venerated objects, Johnson was convicted, sentenced to one year in prison, and fined $2,000. The Supreme Court reversed his conviction. Justice William J. Brennan Jr. wrote in the decision that "if there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea offensive or disagreeable."[226] Congress then passed a federal law barring flag burning, but the Supreme Court struck it down as well in United States v. Eichman (1990).[227][228] A Flag Desecration Amendment to the U.S. Constitution has been proposed repeatedly in Congress since 1989, and in 2006 failed to pass the Senate by a single vote.[229]

Falsifying military awards

While the unauthorized wear or sale of the

Compelled speech

The Supreme Court has determined that the First Amendment also protects citizens from being compelled by the government to say or to pay for certain speech.

In

In National Institute of Family and Life Advocates v. Becerra (2018), the Court ruled that a California law requiring crisis pregnancy centers to post notices informing patients they can obtain free or low-cost abortions and include the number of the state agency that can connect the women with abortion providers violated those centers' right to free speech.[235]

In Janus v. AFSCME (2018), the Court ruled that requiring a public sector employee to pay dues to a union of which he is not a member violated the First Amendment. According to the Court, "the First Amendment does not permit the government to compel a person to pay for another party's speech just because the government thinks that the speech furthers the interests of the person who does not want to pay." The Court also overruled Abood v. Detroit Board of Education (1977), which had upheld legally obligating public sector employees to pay such dues.[236]

Commercial speech

Commercial speech is speech done on behalf of a company or individual for the purpose of making a profit. Unlike political speech, the Supreme Court does not afford commercial speech full protection under the First Amendment. To effectively distinguish commercial speech from other types of speech for purposes of litigation, the Court uses a list of four indicia:[237]

- The contents do "no more than propose a commercial transaction".

- The contents may be characterized as advertisements.

- The contents reference a specific product.

- The disseminator is economically motivated to distribute the speech.

Alone, each indicium does not compel the conclusion that an instance of speech is commercial; however, "[t]he combination of all these characteristics ... provides strong support for ... the conclusion that the [speech is] properly characterized as commercial speech."[238]

In Valentine v. Chrestensen (1942),[239] the Court upheld a New York City ordinance forbidding the "distribution in the streets of commercial and business advertising matter", ruling the First Amendment protection of free speech did not include commercial speech.[240]

In Virginia State Pharmacy Board v. Virginia Citizens Consumer Council (1976),[241] the Court overturned Valentine and ruled that commercial speech was entitled to First Amendment protection:

What is at issue is whether a State may completely suppress the dissemination of concededly truthful information about entirely lawful activity, fearful of that information's effect upon its disseminators and its recipients. ... [W]e conclude that the answer to this one is in the negative.[242]

In Ohralik v. Ohio State Bar Association (1978),[243] the Court ruled that commercial speech was not protected by the First Amendment as much as other types of speech:

We have not discarded the 'common-sense' distinction between speech proposing a commercial transaction, which occurs in an area traditionally subject to government regulation, and other varieties of speech. To require a parity of constitutional protection for commercial and noncommercial speech alike could invite a dilution, simply by a leveling process, of the force of the [First] Amendment's guarantee with respect to the latter kind of speech.[244]

In Central Hudson Gas & Electric Corp. v. Public Service Commission (1980),[245] the Court clarified what analysis was required before the government could justify regulating commercial speech:

- Is the expression protected by the First Amendment? Lawful? Misleading? Fraud?

- Is the asserted government interest substantial?

- Does the regulation directly advance the governmental interest asserted?

- Is the regulation more extensive than is necessary to serve that interest?

Six years later, the U.S. Supreme Court, applying the Central Hudson standards in

School speech

In Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969),[248] the Supreme Court extended free speech rights to students in school. The case involved several students who were punished for wearing black armbands to protest the Vietnam War. The Court ruled that the school could not restrict symbolic speech that did not "materially and substantially" interrupt school activities.[249] Justice Abe Fortas wrote:

First Amendment rights, applied in light of the special characteristics of the school environment, are available to teachers and students. It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate. ... [S]chools may not be enclaves of totalitarianism. School officials do not possess absolute authority over their students. Students ... are possessed of fundamental rights which the State must respect, just as they themselves must respect their obligations to the State.[250]

In Healy v. James (1972), the Court ruled that Central Connecticut State College's refusal to recognize a campus chapter of Students for a Democratic Society was unconstitutional, reaffirming Tinker.[251]

However, since 1969 the Court has also placed several limitations on Tinker. In

In 2014, the University of Chicago released the "Chicago Statement", a free speech policy statement designed to combat censorship on campus. This statement was later adopted by a number of top-ranked universities including Princeton University, Washington University in St. Louis, Johns Hopkins University, and Columbia University.[257][258]

Internet access

In

Obscenity

According to the U.S. Supreme Court, the First Amendment's protection of free speech does not apply to obscene speech. Therefore, both the federal government and the states have tried to prohibit or otherwise restrict obscene speech, in particular the form that is now[update] called pornography. As of 2019[update], pornography, except for child pornography, is in practice free of governmental restrictions in the United States, though pornography about "extreme" sexual practices is occasionally prosecuted. The change in the twentieth century, from total prohibition in 1900 to near-total tolerance in 2000, reflects a series of court cases involving the definition of obscenity. The U.S. Supreme Court has found that most pornography is not obscene, a result of changing definitions of both obscenity and pornography.[39] The legal tolerance also reflects changed social attitudes: one reason there are so few prosecutions for pornography is that juries will not convict.[262]

In

The Supreme Court ruled in Roth v. United States (1957)[266] that the First Amendment did not protect obscenity.[265] It also ruled that the Hicklin test was inappropriate; instead, the Roth test for obscenity was "whether to the average person, applying contemporary community standards, the dominant theme of the material, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest".[267] This definition proved hard to apply, however, and in the following decade, members of the Court often reviewed films individually in a court building screening room to determine if they should be considered obscene.[268] Justice Potter Stewart, in Jacobellis v. Ohio (1964),[269] famously said that, although he could not precisely define pornography, "I know it when I see it".[270][271]

The Roth test was expanded when the Court decided Miller v. California (1973).[272] Under the Miller test, a work is obscene if:

(a) 'the average person, applying contemporary community standards' would find the work, as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest ... (b) ... the work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct specifically defined by the applicable state law, and (c) ... the work, taken as a whole, lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.[273]

"Community" standards—not national standards—are applied to determine whether allegedly obscene material appeals to the prurient interest and is patently offensive.[265] By contrast, the question whether a work lacks serious value depends upon "whether a reasonable person would find such value in the material, taken as a whole."[274]

Child pornography is not subject to the Miller test, as the Supreme Court decided in New York v. Ferber (1982) and Osborne v. Ohio (1990),[275][276] ruling that the government's interest in protecting children from abuse was paramount.[277][278]

Personal possession of obscene material in the home may not be prohibited by law. In Stanley v. Georgia (1969),[279] the Court ruled that "[i]f the First Amendment means anything, it means that a State has no business telling a man, sitting in his own house, what books he may read or what films he may watch."[144] However, it is constitutionally permissible for the government to prevent the mailing or sale of obscene items, though they may be viewed only in private. Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition (2002)[280] further upheld these rights by invalidating the Child Pornography Prevention Act of 1996, holding that, because the act "[p]rohibit[ed] child pornography that does not depict an actual child" (simulated child pornography) it was overly broad and unconstitutional under the First Amendment[281] and:

First Amendment freedoms are most in danger when the government seeks to control thought or to justify its laws for that impermissible end. The right to think is the beginning of freedom, and speech must be protected from the government because speech is the beginning of thought.[282]

In United States v. Williams (2008),[283] the Court upheld the PROTECT Act of 2003, ruling that prohibiting offers to provide and requests to obtain child pornography did not violate the First Amendment, even if a person charged under the Act did not possess child pornography.[284][285]

Memoirs of convicted criminals

In some states, there are

Defamation

American tort liability for defamatory speech or publications traces its origins to English common law. For the first two hundred years of American jurisprudence, the basic substance of defamation law continued to resemble that existing in England at the time of the Revolution. An 1898 American legal textbook on defamation provides definitions of libel and slander nearly identical to those given by William Blackstone and Edward Coke. An action of slander required the following:[289]

- Actionable words, such as those imputing the injured party: is guilty of some offense, suffers from a contagious disease or psychological disorder, is unfit for public office because of moral failings or an inability to discharge his or her duties, or lacks integrity in profession, trade or business;

- That the charge must be false;

- That the charge must be articulated to a third person, verbally or in writing;

- That the words are not subject to legal protection, such as those uttered in Congress; and

- That the charge must be motivated by malice.

An action of libel required the same five general points as slander, except that it specifically involved the publication of defamatory statements.[290] For certain criminal charges of libel, such as seditious libel, the truth or falsity of the statements was immaterial, as such laws were intended to maintain public support of the government and true statements could damage this support even more than false ones.[291] Instead, libel placed specific emphasis on the result of the publication. Libelous publications tended to "degrade and injure another person" or "bring him into contempt, hatred or ridicule".[290]

Concerns that defamation under common law might be incompatible with the new republican form of government caused early American courts to struggle between William Blackstone's argument that the punishment of "dangerous or offensive writings ... [was] necessary for the preservation of peace and good order, of government and religion, the only solid foundations of civil liberty" and the argument that the need for a free press guaranteed by the Constitution outweighed the fear of what might be written.[291] Consequently, very few changes were made in the first two centuries after the ratification of the First Amendment.

The Supreme Court's ruling in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964)[152] fundamentally changed American defamation law. The case redefined the type of "malice" needed to sustain a libel case. Common law malice consisted of "ill-will" or "wickedness". Now, a public officials seeking to sustain a civil action against a tortfeasor needed to prove by "clear and convincing evidence" that there was actual malice. The case involved an advertisement published in The New York Times indicating that officials in Montgomery, Alabama had acted violently in suppressing the protests of African-Americans during the civil rights movement. The Montgomery Police Commissioner, L. B. Sullivan, sued the Times for libel, saying the advertisement damaged his reputation. The Supreme Court unanimously reversed the $500,000 judgment against the Times. Justice Brennan suggested that public officials may sue for libel only if the statements in question were published with "actual malice"—"knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not".[292][293] In sum, the court held that "the First Amendment protects the publication of all statements, even false ones, about the conduct of public officials except when statements are made with actual malice (with knowledge that they are false or in reckless disregard of their truth or falsity)."[294]

While actual malice standard applies to public officials and public figures,[295] in Philadelphia Newspapers v. Hepps (1988),[296] the Court found that, with regard to private individuals, the First Amendment does "not necessarily force any change in at least some features of the common-law landscape".[297] In Dun & Bradstreet, Inc. v. Greenmoss Builders, Inc. (1985)[298] the Court ruled that "actual malice" need not be shown in cases involving private individuals, holding that "[i]n light of the reduced constitutional value of speech involving no matters of public concern ... the state interest adequately supports awards of presumed and punitive damages—even absent a showing of 'actual malice'."[299][300] In Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc. (1974), the Court ruled that a private individual had to prove malice only to be awarded punitive damages, not actual damages.[301][302] In Hustler Magazine v. Falwell (1988),[303] the Court extended the "actual malice" standard to intentional infliction of emotional distress in a ruling which protected parody, in this case a fake advertisement in Hustler suggesting that evangelist Jerry Falwell's first sexual experience had been with his mother in an outhouse. Since Falwell was a public figure, the Court ruled that "importance of the free flow of ideas and opinions on matters of public interest and concern" was the paramount concern, and reversed the judgement Falwell had won against Hustler for emotional distress.[304]

In Milkovich v. Lorain Journal Co. (1990),[305] the Court ruled that the First Amendment offers no wholesale exception to defamation law for statements labeled "opinion", but instead that a statement must be provably false (falsifiable) before it can be the subject of a libel suit.[306] Nonetheless, it has been argued that Milkovich and other cases effectively provide for an opinion privilege.[307]

Private action

Despite the common misconception that the First Amendment prohibits anyone from limiting free speech,[2] the text of the amendment prohibits only the federal government, the states and local governments from doing so.[308]

State constitutions provide free speech protections similar to those of the U.S. Constitution. In a few states, such as California, a state constitution has been interpreted as providing more comprehensive protections than the First Amendment. The Supreme Court has permitted states to extend such enhanced protections, most notably in Pruneyard Shopping Center v. Robins.[309] In that case, the Court unanimously ruled that while the First Amendment may allow private property owners to prohibit trespass by political speakers and petition-gatherers, California was permitted to restrict property owners whose property is equivalent to a traditional public forum (often shopping malls and grocery stores) from enforcing their private property rights to exclude such individuals.[310] However, the Court did maintain that shopping centers could impose "reasonable restrictions on expressive activity".[311] Subsequently, New Jersey, Colorado, Massachusetts and Puerto Rico courts have adopted the doctrine;[312][313] California's courts have repeatedly reaffirmed it.[314]

Freedom of the press

The free speech and free press clauses have been interpreted as providing the same protection to speakers as to writers, except for radio and television wireless broadcasting which have, for historical reasons, been given less constitutional protections.[315] The Free Press Clause protects the right of individuals to express themselves through publication and dissemination of information, ideas and opinions without interference, constraint or prosecution by the government.[132][133] This right was described in Branzburg v. Hayes as "a fundamental personal right" that is not confined to newspapers and periodicals, but also embraces pamphlets and leaflets.[316] In Lovell v. City of Griffin (1938),[317] Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes defined "press" as "every sort of publication which affords a vehicle of information and opinion".[318] This right has been extended to media including newspapers, books, plays, movies, and video games.[319] While it is an open question whether people who blog or use social media are journalists entitled to protection by media shield laws,[320] they are protected equally by the Free Speech Clause and the Free Press Clause, because both clauses do not distinguish between media businesses and nonprofessional speakers.[132][133][321][322] This is further shown by the Supreme Court consistently refusing to recognize the First Amendment as providing greater protection to the institutional media than to other speakers.[323][324][325] For example, in a case involving campaign finance laws the Court rejected the "suggestion that communication by corporate members of the institutional press is entitled to greater constitutional protection than the same communication by" non-institutional-press businesses.[326] Justice Felix Frankfurter stated in a concurring opinion in another case succinctly: "[T]he purpose of the Constitution was not to erect the press into a privileged institution but to protect all persons in their right to print what they will as well as to utter it."[327] In Mills v. Alabama (1943) the Supreme Court laid out the purpose of the free press clause:

Whatever differences may exist about interpretations of the First Amendment, there is practically universal agreement that a major purpose of that Amendment was to protect the free discussion of governmental affairs. This, of course, includes discussions of candidates, structures and forms of government, the manner in which government is operated or should be operated, and all such matters relating to political processes. The Constitution specifically selected the press, which includes not only newspapers, books, and magazines, but also humble leaflets and circulars, see Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U. S. 444, to play an important role in the discussion of public affairs. Thus, the press serves and was designed to serve as a powerful antidote to any abuses of power by governmental officials, and as a constitutionally chosen means for keeping officials elected by the people responsible to all the people whom they were selected to serve. Suppression of the right of the press to praise or criticize governmental agents and to clamor and contend for or against change, which is all that this editorial did, muzzles one of the very agencies the Framers of our Constitution thoughtfully and deliberately selected to improve our society and keep it free.[328]

A landmark decision for press freedom came in Near v. Minnesota (1931),[329] in which the Supreme Court rejected prior restraint (pre-publication censorship). In this case, the Minnesota legislature passed a statute allowing courts to shut down "malicious, scandalous and defamatory newspapers", allowing a defense of truth only in cases where the truth had been told "with good motives and for justifiable ends".[330] The Court applied the Free Press Clause to the states, rejecting the statute as unconstitutional. Hughes quoted Madison in the majority decision, writing, "The impairment of the fundamental security of life and property by criminal alliances and official neglect emphasizes the primary need of a vigilant and courageous press."[331]

However, Near also noted an exception, allowing prior restraint in cases such as "publication of sailing dates of transports or the number or location of troops".[332] This exception was a key point in another landmark case four decades later: New York Times Co. v. United States (1971),[333] in which the administration of President Richard Nixon sought to ban the publication of the Pentagon Papers, classified government documents about the Vietnam War secretly copied by analyst Daniel Ellsberg. The Court found that the Nixon administration had not met the heavy burden of proof required for prior restraint. Justice Brennan, drawing on Near in a concurrent opinion, wrote that "only governmental allegation and proof that publication must inevitably, directly, and immediately cause the occurrence of an evil kindred to imperiling the safety of a transport already at sea can support even the issuance of an interim restraining order." Justices Black and Douglas went still further, writing that prior restraints were never justified.[334]

The courts have rarely treated content-based regulation of journalism with any sympathy. In Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo (1974),[335] the Court unanimously struck down a state law requiring newspapers criticizing political candidates to publish their responses. The state claimed the law had been passed to ensure journalistic responsibility. The Supreme Court found that freedom, but not responsibility, is mandated by the First Amendment and so it ruled that the government may not force newspapers to publish that which they do not desire to publish.[336]

Content-based regulation of television and radio, however, have been sustained by the Supreme Court in various cases. Since there is a limited number of frequencies for non-cable television and radio stations, the government licenses them to various companies. However, the Supreme Court has ruled that the problem of scarcity does not allow the raising of a First Amendment issue. The government may restrain broadcasters, but only on a content-neutral basis. In

State governments retain the right to tax newspapers, just as they may tax other commercial products. Generally, however, taxes that focus exclusively on newspapers have been found unconstitutional. In Grosjean v. American Press Co. (1936),[338] the Court invalidated a state tax on newspaper advertising revenues, holding that the role of the press in creating "informed public opinion" was vital.[339] Similarly, some taxes that give preferential treatment to the press have been struck down. In Arkansas Writers' Project v. Ragland (1987),[340] for instance, the Court invalidated an Arkansas law exempting "religious, professional, trade and sports journals" from taxation since the law amounted to the regulation of newspaper content. In Leathers v. Medlock (1991),[341] the Supreme Court found that states may treat different types of the media differently, such as by taxing cable television, but not newspapers. The Court found that "differential taxation of speakers, even members of the press, does not implicate the First Amendment unless the tax is directed at, or presents the danger of suppressing, particular ideas."[342]

In

Petition and assembly

The Petition Clause protects the right "to petition the government for a redress of grievances".[132] The right expanded over the years: "It is no longer confined to demands for 'a redress of grievances', in any accurate meaning of these words, but comprehends demands for an exercise by the government of its powers in furtherance of the interest and prosperity of the petitioners and of their views on politically contentious matters."[346] The right to petition the government for a redress of grievances therefore includes the right to communicate with government officials, lobbying government officials and petitioning the courts by filing lawsuits with a legal basis.[322] The Petition Clause first came to prominence in the 1830s, when Congress established the gag rule barring anti-slavery petitions from being heard; the rule was overturned by Congress several years later. Petitions against the Espionage Act of 1917 resulted in imprisonments. The Supreme Court did not rule on either issue.[346]

In California Motor Transport Co. v. Trucking Unlimited (1972),[347] the Supreme Court said the right to petition encompasses "the approach of citizens or groups of them to administrative agencies (which are both creatures of the legislature, and arms of the executive) and to courts, the third branch of Government. Certainly the right to petition extends to all departments of the Government. The right of access to the courts is indeed but one aspect of the right of petition."[348] Today, thus, this right encompasses petitions to all three branches of the federal government—the Congress, the executive and the judiciary—and has been extended to the states through incorporation.[346][349] According to the Supreme Court, "redress of grievances" is to be construed broadly: it includes not solely appeals by the public to the government for the redressing of a grievance in the traditional sense, but also, petitions on behalf of private interests seeking personal gain.[350] The right protects not only demands for "a redress of grievances" but also demands for government action.[346][350] The petition clause includes according to the Supreme Court the opportunity to institute non-frivolous lawsuits and mobilize popular support to change existing laws in a peaceful manner.[349]

In Borough of Duryea v. Guarnieri (2011),[351] the Supreme Court stated regarding the Free Speech Clause and the Petition Clause:

It is not necessary to say that the two Clauses are identical in their mandate or their purpose and effect to acknowledge that the rights of speech and petition share substantial common ground ... Both speech and petition are integral to the democratic process, although not necessarily in the same way. The right to petition allows citizens to express their ideas, hopes, and concerns to their government and their elected representatives, whereas the right to speak fosters the public exchange of ideas that is integral to deliberative democracy as well as to the whole realm of ideas and human affairs. Beyond the political sphere, both speech and petition advance personal expression, although the right to petition is generally concerned with expression directed to the government seeking redress of a grievance.[351]

The right of assembly is the individual right of people to come together and collectively express, promote, pursue, and defend their collective or shared ideas.[352] This right is equally important as those of free speech and free press, because, as observed by the Supreme Court of the United States in De Jonge v. Oregon, 299 U.S. 353, 364, 365 (1937), the right of peaceable assembly is "cognate to those of free speech and free press and is equally fundamental ... [It] is one that cannot be denied without violating those fundamental principles of liberty and justice which lie at the base of all civil and political institutions—principles which the Fourteenth Amendment embodies in the general terms of its due process clause ... The holding of meetings for peaceable political action cannot be proscribed. Those who assist in the conduct of such meetings cannot be branded as criminals on that score. The question ... is not as to the auspices under which the meeting is held but as to its purpose; not as to the relations of the speakers, but whether their utterances transcend the bounds of the freedom of speech which the Constitution protects."[346] The right of peaceable assembly was originally distinguished from the right to petition.[346] In United States v. Cruikshank (1875),[353] the first case in which the right to assembly was before the Supreme Court,[346] the court broadly declared the outlines of the right of assembly and its connection to the right of petition:

The right of the people peaceably to assemble for the purpose of petitioning Congress for a redress of grievances, or for anything else connected with the powers or duties of the National Government, is an attribute of national citizenship, and, as such, under protection of, and guaranteed by, the United States. The very idea of a government, republican in form, implies a right on the part of its citizens to meet peaceably for consultation in respect to public affairs and to petition for a redress of grievances.[354]

Justice

Freedom of association

Although the First Amendment does not explicitly mention freedom of association, the Supreme Court ruled, in NAACP v. Alabama (1958),[359][360] that this freedom was protected by the amendment and that privacy of membership was an essential part of this freedom.[361] In Roberts v. United States Jaycees (1984), the Court stated that "implicit in the right to engage in activities protected by the First Amendment" is "a corresponding right to associate with others in pursuit of a wide variety of political, social, economic, educational, religious, and cultural ends".[362] In Roberts the Court held that associations may not exclude people for reasons unrelated to the group's expression, such as gender.[363]

However, in Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Group of Boston (1995),[364] the Court ruled that a group may exclude people from membership if their presence would affect the group's ability to advocate a particular point of view.[365] Likewise, in Boy Scouts of America v. Dale (2000),[366] the Court ruled that a New Jersey law, which forced the Boy Scouts of America to admit an openly gay member, to be an unconstitutional abridgment of the Boy Scouts' right to free association.[367]

In Americans for Prosperity Foundation v. Bonta (2021), the Court ruled that California's requiring disclosure of the identities of nonprofit companies' big-money donors did not serve a narrowly tailored government interest and, thus, violated those donors' First Amendment rights.[368]

See also

- Censorship in the United States

- First Amendment audits

- Free speech zone

- Freedom of speech

- Government speech

- List of amendments to the United States Constitution

- List of United States Supreme Court cases involving the First Amendment

- Marketplace of ideas

- Military expression

- Photography Is Not a Crime