Foreign-body giant cell

A foreign-body giant cell is a collection of fused

The human body goes through several steps when exposed to foreign biomaterial including

Foreign body giant cells are formed through signaling from IL-4 and IL-13, and may fuse to produce a multinucleated cell with up to 200 nuclei within its cytoplasm.[5]

Formation

Macrophages are phagocytic cells that are produced during an injury or infection.[1] They defend against infectious microorganisms, but also play a role in homeostasis and wound healing.[1] Through the release of Interleukin 4 (IL-4) and Interleukin 13 (IL-13) by TH2, or T helper cells, and mast cells, these macrophages can fuse to form foreign body giant cells.[1][4]

The macrophages are initially attracted to the injury/infection site through a variety of

Function

Foreign body giant cells are involved in the foreign body reaction, phagocytosis, and subsequent degradation of biomaterials which may lead to failure of the implanted material.[4] When produced, the FBGC's place themselves along the surface of the implantation, and will remain there for as long as the foreign material remains in the body.[1]

Macrophages and FBGC's will begin to produce inflammatory molecules in response to the biomaterial.[4] These inflammatory molecules will signal other molecules to respond and begin the process of wound healing.[4]

Microorganisms, particles, and debris that were produced from inserting the biomaterial may be engulfed by macrophages.[1] If the substance is too large for one macrophage, the FBGC's can attempt to engulf the foreign material for degradation.[1]

FBGC's will also begin to produce

-

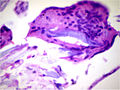

Foreign-body giant cell reaction to a suture. H&E stain.

-

Micrograph showing a foreign body engulfed by a giant cell. H&E stain.

-

Foreign body giant cell reaction to silicone leakage from breast implant. H&E stain.