Geography of Scotland in the Middle Ages

The geography of Scotland in the Middle Ages covers all aspects of the land that is now Scotland, including physical and human, between the departure of the Romans in the early fifth century from what are now the southern borders of the country, to the adoption of the major aspects of the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century. Scotland was defined by its physical geography, with its long coastline of inlets, islands and inland

Roman occupation of what is now southern Scotland seems to have had very little impact on settlement patterns, with

From the reign of David I (r. 1124–53), there is evidence of burghs, particularly on the east coast, which are the first identifiable towns in Scotland. Probably based on existing settlements, they grew in number and significance through the Medieval period. More than 50 royal burghs are known to have been established by the end of the thirteenth century and a similar number of baronial and ecclesiastical burghs were created between 1450 and 1516, acting as focal points for administration, as well as local and international trade. In the early Middle Ages the country was divided between speakers of Gaelic, Pictish, Cumbric and English. Over the next few centuries Cumbric and Pictish were gradually overlaid and replaced by Gaelic, English and Norse. From at least the reign of David I, Gaelic was replaced by French as the language of the court and nobility. In the late Middle Ages Scots, derived mainly from Old English, became the dominant language.

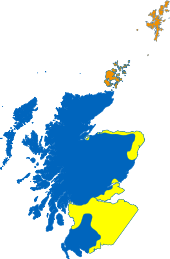

In the middle of this period, through a process of conquest, consolidation and treaty, the boundaries of Scotland were gradually extended from a small area under direct control of the

Physical

Modern Scotland is half the size of England and Wales in area, but with its many inlets, islands and inland

The defining factor in the geography of Scotland is the distinction between the

Settlement and demography

Roman influence beyond

Place-name evidence suggests that the densest areas of Pictish settlement were in the north-east coastal plain: in modern Fife, Perthshire, Angus, Aberdeen and around the Moray Firth, although later Gaelic migration may have erased some Pictish names from the record.[15] Early Gaelic settlement appears to have been in the regions of the western mainland of Scotland between Cowal and Ardnamurchan, and the adjacent islands, later extending up the West coast in the eighth century.[16] There is place name and archaeological evidence of Anglian settlement in south-east Scotland reaching into West Lothian, and to a lesser extent into south-western Scotland.[17] Later Norse settlement was probably most extensive in Orkney and Shetland, with lighter settlement in the Western Islands, particularly the Hebrides and on the mainland in Caithness, stretching along fertile river valleys through Sutherland and into Ross. There was also extensive settlement in Bernicia stretching into the modern borders and Lowlands.[18]

From the reign of David I, there are records of

There are almost no written sources from which to re-construct the demography of early medieval Scotland. Estimates have been made of a population of 10,000 inhabitants in

Language

Modern linguists divide Celtic languages into two major groups: the

In the Northern Isles the Norse language brought by Scandinavian occupiers and settlers evolved into the local Norn, which lingered until the end of the eighteenth century[33] and Norse may also have survived as a spoken language until the sixteenth century in the Outer Hebrides.[34] French, Flemish and particularly English became the main language of Scottish burghs, most of which were in the south and east, an area to which Anglian settlers had already brought a form of Old English. In the later part of the twelfth century, the writer Adam of Dryburgh described Lowland Lothian as "the Land of the English in the Kingdom of the Scots".[35] At least from the accession of David I, Gaelic ceased to be the main language of the royal court and was replaced by Norman French, to be followed by the Chancery, the castles of nobles and the upper order of the Church.[36]

In the late Middle Ages, Middle Scots, often simply but inaccurately called English, became the dominant language of the country. It was derived largely from Old English, with the addition of elements from Gaelic and French. Although resembling the language spoken in northern England, it became a distinct language from the late fourteenth century.[37] It was adopted by the ruling elite as they gradually abandoned French. By the fifteenth century it was the language of government, with acts of parliament, council records and treasurer's accounts almost all using it from the reign of James I onwards. As a result, Gaelic, once dominant north of the Tay, began a steady decline.[37]

Political

At its foundation in the tenth century, the combined Gaelic and Pictish kingdom of Alba contained only a small proportion of modern Scotland. Even when these lands were added to in the tenth and eleventh centuries, the term "Scotia" was applied in sources only to the region between the Forth, the central Grampians and the River Spey, and only began to be used to describe all of the lands under the authority of the Scottish crown from the second half of the twelfth century.[38] The expansion of Alba into the wider kingdom of Scotland was a gradual process combining external conquest and the suppression of occasional rebellions, with the extension of seigniorial power through the placement of effective agents of the crown.[39] Neighbouring independent kings became subject to Alba and eventually disappeared from the records. In the ninth century the term mormaer, meaning "great steward", began to appear in the records to describe the rulers of Moray, Strathearn, Buchan, Angus and Mearns, who may have acted as "marcher lords" for the kingdom to counter the Viking threat.[40] Later the process of consolidation is associated with the feudalism introduced by David I, which, particularly in the east and south where the crown's authority was greatest, saw the placement of lordships, often based on castles, and the creation of administrative sheriffdoms, which overlay the pattern of local thegns.[39]

Most of the regions of what became Scotland had strong cultural and economic ties elsewhere: to England, Ireland, Scandinavian and mainland Europe. Internal communications were difficult and the country lacked an obvious geographical centre; the king kept an itinerant court, with no "capital" as such.

Until the thirteenth century the borders with England were very fluid.

Notes

- ISBN 0192100548, pp. 10–11.

- ^ ISBN 0521362911, p. 234.

- ISBN 0709923856, p. 174.

- ISBN 0415278805, p. 2.

- ISBN 0333567617, pp. 9–20.

- ISBN 0761478833, p. 13.

- ^ ISBN 0748602763, pp. 39–40.

- ^ A. G. Ogilvie, Great Britain: Essays in Regional Geography (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1952), p. 421.

- ^ R. R. Sellmen, Medieval English Warfare (London: Taylor & Francis, 1964), p. 29.

- ISBN 0748617361, p. 175.

- ^ ISBN 0748617361, pp. 224–5.

- ISBN 0748617361, p. 226.

- ISBN 0748617361, p. 227.

- ISBN 0520046692, p. 274.

- ^ ISBN 058250578X, p. 116.

- ISBN 0582772923, p. 53.

- ISBN 0415301491, p. 226.

- ISBN 0748606416, pp. 37–41.

- ISBN 074860104X, p. 98.

- ^ ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, pp. 136–40.

- ^ ISBN 0415278805, p. 78.

- ISBN 0198206151, pp. 38–76.

- ISBN 0333567617, pp. 122–3.

- ^ ISBN 0521547407, pp. 21–2.

- ISBN 0748612343, pp. 17–20.

- ^ R. E. Tyson, "Population Patterns", in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (New York, 2001), pp. 487–8.

- ISBN 0631217851, pp. 109–11.

- ISBN 0748602763, p. 61.

- ISBN 0521473853, pp. 8–10.

- ISBN 0415278805, p. 4.

- ISBN 0718500849, p. 238.

- ISBN 074860104X, p. 14.

- ^ G. Lamb, "The Orkney Tongue" in D. Omand, ed., The Orkney Book (Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2003), p. 250.

- ISBN 0951257374, p. 97.

- ISBN 1862321515, p. 133.

- ISBN 0748616152, p. 61.

- ^ ISBN 0748602763, pp. 60–67.

- ISBN 9004175334, p. 85.

- ^ ISBN 0415122317, p. 97.

- ISBN 0333567617, p. 22.

- ISBN 0521892295, pp. 16–17.

- ^ J. Bannerman, "MacDuff of Fife," in A. Grant & K. Stringer, eds., Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community, Essays Presented to G. W. S. Barrow (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1993), pp. 22–23.

- ^ P. G. B. McNeill and Hector L. MacQueen, eds, Atlas of Scottish History to 1707 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1996), pp. 159–63.

- ISBN 0748602763, pp. 14–15.

- ^ ISBN 0333567617, p. 55.

- ISBN 0748620222, p. 11.

- ISBN 0198208499, p. 64.

- ISBN 184158696X, p. 204.

- ISBN 0415130417, p. 101.

- ^ ISBN 1843840960, pp. 21.

- ISBN 0748602763, p. 5.

- ISBN 0226079872, p. 41.