Fortriu

Fortriu (

Name

The people of Fortriu left no surviving indigenous writings

A connected

Modern scholars writing in English usually refer to the kingdom using the name Fortriu and the adjective Verturian, and use the name the Wærteras to refer to the people as an

History

Roman Iron Age

Fortriu is first recorded by the Roman author

The Verturiones may have emerged as part of a pattern seen in other Roman frontier zones such as Germany, where areas beyond the border saw population groups amalgamating into fewer but larger political units.[15]

As well as the two Pictish groupings, the conspiracy of 367-368 included Scotti from Ireland; Attacotti whose origins are uncertain but likely to have been somewhere within the British Isles; and Franks and Saxons from across the North Sea; suggesting high levels of intercommunication between the Verturiones and the peoples of Ireland and continental Europe.[16] The conspiracy may have been caused by a decline in the level if subsidies given to barbarian tribes by the emperor Valentinian.[17] The fact that Fullofaudes, the leader of the northern Roman troops, was captured rather than killed suggests that the Pictish invaders may have been motivated mainly by extracting treasure.[18]

Verturian hegemony

After the 4th century Fortriu is not explicitly mentioned in documentary sources until 664, but there are indications that Fortriu's later power may have been foreshadowed in the late 6th century.

By the end of the 7th century Fortriu had established a dominant position over most or all of the Picts, one of the most significant developments in the history of early medieval Scotland,

The continuing power of the kings of Fortriu over the Picts can be seen in the activities of Bridei son of Beli's successors.

A series of campaigns under

A period of instability in Fortriu following the death of

The Viking Age

The dominance of Fortriu and the

The Viking Kings of Dublin Amlaíb and Auisle are recorded in the Annals of Ulster going to Fortriu and plundering "the entire Pictish nation" in 866.[34] Although the chronology of written sources is confused, they probably occupied Fortriu for three years and took hostages,[35] before attacking Dumbarton Rock in 870 and returning to Dublin in 871, bringing with them "a great prey of English, and Britons and Picts."[36]

Fragmentation and disappearance

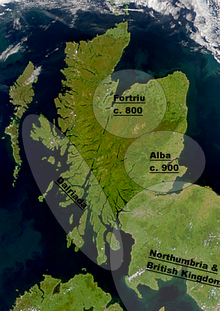

Fortriu continued to be recorded into the early 10th century, suggesting a degree of continuity with the earlier period of over-kingship.

The complete disappearance of the name Fortriu beyond this point suggests that it fragmented into its successor polities – the provinces of Moray and Ross – during the 10th century.[40] Moray is first recorded in an entry in the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba for the reign of Malcolm I, which lasted from 943 to 954;[41] while Ross first appears in the documentary record in a hagiography of the Scottish-born saint Cathróe of Metz, written in Metz between 971 and 976.[42]

Location

From the 19th century until 2006 most historians believed that the kingdom recorded as Fortriu in the Irish annals lay south of the Mounth in present-day central Scotland, based on the work of E. W. Robertson and W. F. Skene.[43] Robertson, in his 1862 work Scotland under her Early Kings, identified Fortriu as comprising Clackmannanshire, Menteith and west Fife on the left bank of the Forth, arguing that the names of both Fortriu and the medieval deanery of Fothriff derived from an earlier hypothetical *Forthreim, which he translated as "Forth Realm".[4] This argument is based on unsound etymology, however, as Fothriff derives from the Gaelic words foithir and Fib and means "district appended to Fife", while Fortriu is related to the earlier Latin name Verturiones.[4] Skene, in his 3 volume work Celtic Scotland: A History of Ancient Alban, published between 1876 and 1880, identified Fortriu with Strathearn and Menteith, the first province listed in the 12th century document De Situ Albanie, on the basis that a battle recorded by the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba as taking place in Sraith Herenn was also recorded by the Annals of Ulster as the killing of Ímar ua Ímair by the "Men of Fortriu".[44] This argument is also inconclusive, however: Sraith Herenn could refer to either Strathearn in Perthshire, south of the Mounth; or Strathdearn, the valley of the River Findhorn in Moray, north of the Mounth;[45] while the fact that Ímar was killed by the "Men of Fortriu" does not prove that he was killed within the territory of Fortriu.[46] Despite Skene's initial suggestion being tentative, this identification of Fortriu as including western Perthshire became established as a consensus.[47]

However, new research by Alex Woolf seems to have destroyed this consensus, if not the idea itself. A northern recension of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle makes it clear that Fortriu was north of the Mounth (i.e., the eastern Grampians), in the area visited by Columba.[48] The long poem known as The Prophecy of Berchán, written perhaps in the 12th century, but purporting to be a prophecy made in the Early Middle Ages, says that Dub, King of Scotland was killed in the Plain of Fortriu.[49] Another source, the Chronicle of the Kings of Alba, indicates that King Dub was killed at Forres, a location in Moray.[50] Additions to the Chronicle of Melrose confirm that Dub was killed by the men of Moray at Forres.[51]

There can be little or no doubt then that Fortriu centred on northern Scotland. Other Pictish scholars, such as James E. Fraser are now taking it for granted that Fortriu was in the north of Scotland, centred on Moray and Easter Ross, where most early Pictish monuments are located.[1]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f Fraser 2009, p. 50.

- ^ Woolf 2001, p. 106.

- ^ Woolf 2007, p. 31.

- ^ a b c Woolf 2006, p. 188.

- ^ Watson 2004, p. 69.

- OCLC 669641.

- ^ Mallory & Adams 2006, p. 516.

- ^ Woolf 2001, p. 107.

- ^ Woolf 2006, pp. 193, 196.

- ^ Watson 2004, p. 48.

- ^ Watson 2004, p. 68.

- ^ Woolf 2006, pp. 198.

- ^ Noble & Evans 2022, pp. 7, 16.

- ^ Noble & Evans 2022, p. 7.

- ^ Evans 2019, p. 12.

- ^ Fraser 2009, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Fraser 2009, p. 57.

- ^ Fraser 2009, pp. 56–57.

- ^ a b c Noble & Evans 2022, p. 16.

- ^ Fraser 2009, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Foster 2014, p. 136.

- ^ Evans 2019, p. 14.

- ^ Foster 2014, p. 150.

- ^ a b c d e Noble & Evans 2022, p. 18.

- ^ Fraser 2009, p. 202.

- ^ Evans 2019, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Foster 2014, p. 37.

- ^ Márkus 2017, p. 109.

- ^ Ross 2011, p. 100.

- ^ Fraser 2009, pp. 287–288.

- ^ a b Woolf 2007, p. 41.

- ^ Woolf 2007, pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b c Woolf 2007, p. 66.

- ^ Woolf 2007, p. 107.

- ^ Woolf 2007, p. 109.

- ^ Woolf 2007, p. 110.

- ^ a b c Noble & Evans 2022, p. 252.

- ^ Ross 2015, p. 51.

- ^ Ross 2011, p. 46.

- ^ Woolf 2006, pp. 201.

- ^ Woolf 2007, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Evans 2019, p. 31.

- ^ Ross 2011, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Woolf 2006, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Ross 2011, p. 98.

- ^ Woolf 2006, p. 192.

- ^ Woolf 2007, p. 10.

- ^ Woolf 2006, p. 199.

- ^ A. O. Anderson, Early Sources, Vol. I, p. 474.

- ^ A. O. Anderson, Early Sources, Vol. I, p. 473.

- ^ A. O. Anderson, Early Sources, Vol. I, pp. 473–4.

- ^ A. O. Anderson, Early Sources, Vol. I, p. 601.

References

- Anderson, Alan Orr, Early Sources of Scottish History: AD 500-1286, 2 Vols, (Edinburgh, 1922)

- Evans, Nicholas (2019). "A historical introduction to the northern Picts". In Noble, Gordon; Evans, Nicholas (eds.). The King in the North: The Pictish realms of Fortriu and Ce. Collected essays written as part of the University of Aberdeen's Northern Picts project. Edinburgh: Birlinn. pp. 10–38. ISBN 9781780275512.

- Foster, Sally M. (2014). Picts, Scots and Gaels — Early Historic Scotland. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 9781780271910.

- Fraser, James (2009). From Caledonia to Pictland: Scotland to 795. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748612321.

- Hudson, Benjamin T., Kings of Celtic Scotland, (Westport, 1994)

- Mallory, J.P.; Adams, D.Q. (2006), The Oxford introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European world (Repr. ed.), Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford Univ. Press, ISBN 9780199287918

- Márkus, Gilbert (2017). Conceiving a Nation: Scotland to AD 900. New History of Scotland. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748678983.

- Noble, Gordon; Evans, Nicholas (2022). The Picts: Scourge of Rome, Rulers of the North. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 9781780277783.

- Ross, Alasdair (2011). The Kings Of Alba: c.1000-c.1130. Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 9781906566159.

- Ross, Alasdair (2015). Land Assessment and Lordship in Medieval Northern Scotland. Turnhout: Brepols. ISBN 9782503541334.

- Watson, William J. (2004) [1926]. Taylor, Simon (ed.). The Celtic Placenames of Scotland. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 9781841583235.

- Woolf, Alex (2001). "The Verturian Hegemony: A Mirror in the North". In Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carol Ann (eds.). Mercia: an Anglo-Saxon Kingdom in Europe. Leicester: Leicester University Press. pp. 106–112. ISBN 9780826477651.

- Woolf, Alex (October 2006). "Dén Nechtain, Fortriu and the Geography of the Picts". Scottish Historical Review. 85 (2): 182–201. ISSN 0036-9241.

- Woolf, Alex (2007). From Pictland to Alba 789–1070. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 9780748612345.