Christianity in Medieval Scotland

| General |

|---|

| Early |

| Medieval |

|

| Early Modern |

| Eighteenth century to present |

Christianity in medieval Scotland includes all aspects of Christianity in the modern borders of

In the Norman period, from the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries, the Scottish church underwent a series of reforms and transformations. With royal and lay patronage, a clearer parochial structure based around local churches was developed. Large numbers of new monastic foundations, which followed continental forms of reformed monasticism, began to predominate. The Scottish church also established its independence from England, developing a clear diocesan structure and becoming a "special daughter of the see of Rome", but continued to lack Scottish leadership in the form of archbishops.

In the late Middle Ages the problems of schism in the Catholic Church allowed the Scottish Crown to gain greater influence over senior appointments and two archbishoprics had been established by the end of the fifteenth century. Historians have discerned a decline in traditional monastic life in the late Middle Ages, but the mendicant orders of friars grew, particularly in the expanding burghs, emphasised preaching and ministering to the population. New saints and cults of devotion also proliferated. Despite problems over the number and quality of clergy after the Black Death in the fourteenth century, and evidence of heresy in the fifteenth century, the church in Scotland remained stable before the Reformation in the sixteenth century.

Early Middle Ages

Early Christianisation

Before the Middle Ages, most of the population of what is now Scotland practised a form of

The Christianisation of Scotland was carried out by Irish-Scots missionaries and to a lesser extent those from Rome and England.

The means and speed by which the Picts converted to Christianity is uncertain.[15] The process may have begun early.[16] Evidence for this includes the fact that St. Patrick, active in the fifth century, referred in a letter to "apostate Picts", indicating that they had previously been Christian, but had abandoned the faith. In addition the poem Y Gododdin, set in the early sixth century and probably written in what is now Scotland, does not remark on the Picts as pagans.[17] Conversion of the Pictish élite seems likely to have run over a considerable period, beginning in the fifth century and not complete until the seventh[18] and conversion of the general population may have stretched into the eighth century.[11]

Among the key indicators of Christianisation are cemeteries containing long cists which are generally east-west in orientation.

Early church buildings may originally have been wooden, like that excavated at

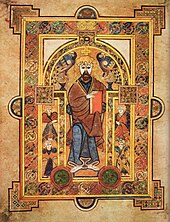

Celtic Christianity

The Celtic Church is a term that has been used by scholars to describe a specific form of Christianity with its origins in the conversion of Ireland, traditionally associated with St. Patrick. This form of Christianity later spread to northern Britain through Iona. It is also used as a general description for the Christian establishment of northern Britain prior to the twelfth century, when new religious institutions and ideologies of primarily French origin began to take root in Scotland. The Celtic form of Christianity has been contrasted with that derived from missions from Rome, which reached southern England in 587 under the leadership of

While Roman and Celtic Christianity were very similar in

In the seventh century the Northumbrian church was increasingly influenced by the Roman form of Christianity. The careers of

By the mid-eighth century, Iona and Ireland had accepted Roman practices.

Early monasticism

While there were a series of reforms of

Scottish monasticism played a major part in the

High Middle Ages

While the official conversion of Scandinavian Scotland took place at the end of the tenth century, there is evidence that Christianity had already made inroads into the Viking controlled

Reformed monasticism

The introduction of continental forms of monasticism to Scotland is associated with Saxon princess

The Augustinians, dedicated to the

Cult of Saints

Like every other Christian country, one of the main features of Medieval Scotland was the

Organisation

Before the twelfth century, in contrast to England, there were few parish churches in Scotland. Churches had collegiate bodies of clergy who served over a wide area, often tied together by devotion to a particular missionary saint.[11] From this period local lay landholders, perhaps following the example of David I, began to adopt the continental practice of building churches on their property for the local population and endowing them with land and a priest. The foundation of these churches began in the south, spreading to the north-east and then the west, being almost universal by the first survey of the Scottish Church for papal taxation in 1274.[57] The administration of these parishes was often given over to local monastic institutions in a process known as appropriation. By the time of the Reformation in the mid-sixteenth century 80 per cent of Scottish parishes were appropriated.[57]

Before the

Late Middle Ages

Church and politics

Late Medieval religion had its political aspects.

As elsewhere in Europe, the collapse of papal authority in the Papal Schism allowed the Scottish Crown to gain effective control of major ecclesiastical appointments within the kingdom. This de facto authority over appointments was formally recognised by the Papacy in 1487. This led to the placement of clients and relatives of the king in key positions, including James IV's illegitimate son

Popular religion

Traditional Protestant historiography tended to stress the corruption and unpopularity of the late Medieval Scottish church, but more recent research has indicated the ways in which it met the spiritual needs of different social groups.

In most Scottish

In the early fourteenth century the Papacy managed to minimise the problem of clerical

Notes

- ISBN 0-14-025422-6, p. 184.

- ISBN 0952502917, p. 41.

- ISBN 0-903903-24-5, p. 63.

- ISBN 086054138X, p. 93.

- ISBN 1-85285-195-3, p. 48.

- ISBN 0809138948, p. 21.

- ISBN 0520218590, pp. 231–3.

- ISBN 0520218590, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Thomas Owen Clancy, "The real St Ninian", The Innes Review, 52 (2001).

- ^ ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, p. 46.

- ^ ISBN 0333567617, pp. 50–1.

- ^ ISBN 0889201668, pp. 77–89.

- ISBN 0333567617, p. 51.

- ^ ISBN 0333567617, pp. 52–3.

- ISBN 0333567617, p. 53.

- ISBN 0748601007, pp. 82–3.

- ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 78–9.

- ^ ISBN 0748602917, pp. 171–2.

- ISBN 0951257331, pp. 57 and 67–71.

- ISBN 1874012105, pp. 27–8.

- ISBN 0713488743, p. 77.

- ^ G. W. S. Barrow, "The childhood of Scottish Christianity: a note on some place-name evidence", in Scottish Studies, 27 (1983), pp. 1–15.

- ISBN 0748612327, p. 89.

- ^ ISBN 0333567617, p. 55.

- ISBN 0748621792, p. 1.

- ISBN 1-904320-02-3, pp. 22–3.

- ISBN 0-85263-748-9, p. 8.

- ISBN 0-415-02992-9, p. 117.

- ISBN 0333567617, pp. 51–2.

- ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, pp. 52–3.

- ISBN 1403972990.

- ISBN 0333567617, pp. 53–4.

- ^ ISBN 0333567617, p. 54.

- ISBN 0-8160-7728-2, pp. 44–5.

- ISBN 0-415-27880-5, p. 9.

- ISBN 0333567617, p. 15.

- ^ "Abernethy round tower" Historic Scotland, retrieved 17 March 2012.

- ^ ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, pp. 117–128.

- ISBN 005003183X, pp. 104–05.

- ISBN 0333567617, p. 58.

- ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, p. 121.

- ^ David N. Dumville, "St Cathróe of Metz and the Hagiography of Exoticism," in John Carey, et al., eds, Irish Hagiography: Saints and Scholars (Dublin, 2001), pp. 172–6.

- ^ ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, pp. 67–8.

- ^ D. E. R. Watt, (ed.), Fasti Ecclesia Scoticanae Medii Aevii ad annum 1638, Scottish Records Society (1969), p. 247.

- ^ "The Diocese of Orkney" Firth's Celtic Scotland, retrieved 9 September 2009.

- ISBN 0-7185-128-20, pp. 82 and 220.

- ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, pp. 69.

- ISBN 1111831688, p. 270.

- ISBN 0-85263-748-9, p. 10.

- ISBN 074860104X, p. 81.

- ISBN 074860104X, p. 64.

- ISBN 0859917657, p. 137.

- ISBN 9004155805.

- ^ ISBN 0748620222, p. 11.

- ISBN 1446475638, p. 76.

- ISBN 1843835622, pp. 178–94.

- ^ ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, pp. 109–117.

- ^ ISBN 1843840960, pp. 26–9.

- ^ G. W. S. Barrow, Robert Bruce (Berkeley CA: University of California Press, 1965), p. 293.

- ^ ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, pp. 197–9.

- ^ ISBN 0748602763, pp. 76–87.

- ISBN 0521444616, pp. 349–50.

- ISBN 052158602X, p. 246.

- ISBN 052158602X, p. 254.

- ^ ISBN 033363358X, p. 147.

- ISBN 052158602X, pp. 244–5.

- ISBN 052158602X, p. 257.

References

- Barrow, G.W.S., The Kingdom of the Scots (Edinburgh, 2003).

- Barrow, G.W.S., Kingship and Unity: Scotland, 1000–1306 (Edinburgh. 1981).

- Broun, Dauvit and Clancy, Thomas Owen (eds.),Spes Scottorum: Hope of the Scots (Edinburgh, 1999).

- Clancy, Thomas Owen, "The real St Ninian", in The Innes Review, 52 (2001).

- Dumville, David N., "St Cathróe of Metz and the Hagiography of Exoticism," in Irish Hagiography: Saints and Scholars, ed. John Carey et al. (Dublin, 2001), pp. 172–6.

- Foster, Sally, Picts, Gaels and Scots: Early Historic Scotland (London, 1996).

- Stringer, Keith J., “Reform Monasticism and Celtic Scotland,” in Edward J. Cowan and R. Andrew McDonald (eds), Alba: Celtic Scotland in the Middle Ages (East Lothian, 2000), pp. 127–65

Further reading

- Crawford, Barbara (ed.), Conversion And Christianity In The North Sea World (St Andrews, 1998)

- Crawford, Barbara (ed.), Scotland In Dark Age Britain (St Andrews, 1996)