God the Father in Western art

For about a thousand years, in obedience to interpretations of specific Bible passages, pictorial depictions of God in Western Christianity had been avoided by Christian artists. At first only the Hand of God, often emerging from a cloud, was portrayed. Gradually, portrayals of the head and later the whole figure were depicted, and by the time of the Renaissance artistic representations of God the Father were freely used in the Western Church.[2]

God the Father can be seen in some late Byzantine Cretan School icons, and ones from the borders of the Catholic and Orthodox worlds, under Western influence, but after the Russian Orthodox Church came down firmly against depicting him in 1667, he can hardly be seen in Russian art. Protestants generally disapprove of the depiction of God the Father, and originally did so strongly.

Background and early history

Early Christians believed that the words of Book of Exodus 33:20 "Thou canst not see my face: for there shall no man see Me and live" and of the Gospel of John 1:18: "No man hath seen God at any time" were meant to apply not only to the Father, but to all attempts at the depiction of the Father.[3]

The

Historically considered, God the Father is more frequently manifested in the Old Testament, while the Son is manifested in the New Testament. Hence it might be said that the Old Testament refers more especially to the history of the Father and the New Testament to that of the Son. Yet, in early depictions of scenes from the Old Testament, artists used the conventional depiction of Jesus to represent the Father,[5] especially in depictions of the story of Adam and Eve, the most frequently depicted Old Testament narrative shown in Early Medieval art, and one that was felt to require the depiction of a figure of God "walking in the garden" (Genesis 3:8).

The account in

It was therefore usual to have depictions of Jesus as Logos taking the place of the Father and creating the world alone, or commanding Noah to construct the ark or speaking to Moses from the Burning bush.[6] There was also a brief period in the 4th century when the Trinity were depicted as three near-identical figures, mostly in depicting scenes from Genesis; the Dogmatic Sarcophagus in the Vatican is the best known example. In isolated cases this iconography is found throughout the Middle Ages, and revived somewhat from the 15th century, though it attracted increasing disapproval from church authorities. A variant is Enguerrand Quarton's contract for the Coronation of the Virgin requiring him to represent the Father and Son of the Holy Trinity as identical figures.[7]

One scholar has suggested that the enthroned figure in the centre of the apse mosaic of Santa Pudenziana in Rome of 390-420, normally regarded as Christ, in fact represents God the Father.[8]

In situations, such as the

The use of religious images in general continued to increase up to the end of the 7th century, to the point that in 695, upon assuming the throne,

The beginning of the 8th century witnessed the suppression and destruction of religious icons as the period of

The end of iconoclasm

The

In his treatise On the Divine Images John of Damascus wrote: "In former times, God who is without form or body, could never be depicted. But now when God is seen in the flesh conversing with men, I make an image of the God whom I see".[14] The implication here is that insofar as God the Father or the Spirit did not become man, visible and tangible, images and portrait icons can not be depicted. So what was true for the whole Trinity before Christ remains true for the Father and the Spirit but not for the Word. John of Damascus wrote:[15]

If we attempt to make an image of the invisible God, this would be sinful indeed. It is impossible to portray one who is without body: invisible, uncircumscribed and without form.

Around 790

The

We decree that the sacred image of our Lord Jesus Christ, the liberator and Savior of all people, must be venerated with the same honor as is given the book of the holy Gospels. For as through the language of the words contained in this book all can reach salvation, so, due to the action which these images exercise by their colors, all wise and simple alike, can derive profit from them.

But images of God the Father were not directly addressed in Constantinople in 869. A list of permitted icons was enumerated at this Council, but images of God the Father were not among them.[17] However, the general acceptance of icons and holy images began to create an atmosphere in which God the Father could be depicted.[citation needed]

Middle ages to the Renaissance

Prior to the 10th century no attempt was made to represent a separate depiction as a full human figure of

It appears that when early artists designed to represent God the Father, fear and awe restrained them from a delineation of the whole person. Typically only a small part would be represented, usually the hand, or sometimes the face, but rarely the whole person. In many images, the figure of the Son supplants the Father, so a smaller portion of the person of the Father is depicted.[18]

By the 12th century depictions of God the Father had started to appear in French

In an early Venetian school Coronation of the Virgin by Giovanni d'Alemagna and Antonio Vivarini, (c. 1443) (see gallery below) the Father is shown in the representation consistently used by other artists later, namely as a patriarch, with benign, yet powerful countenance and with long white hair and a beard, a depiction largely derived from, and justified by, the description of the Ancient of Days in the Old Testament, the nearest approach to a physical description of God in the Old Testament:[20]

. ...the Ancient of Days did sit, whose garment was white as snow, and the hair of his head like the pure wool: his throne was like the fiery flame, and his wheels as burning fire. (Daniel 7:9)

In the Annunciation by

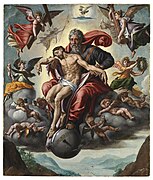

In Renaissance paintings of the adoration of the Trinity, God may be depicted in two ways, either with emphasis on The Father, or the three elements of the Trinity. The most usual depiction of the Trinity in Renaissance art depicts God the Father as an old man, usually with a long beard and patriarchal in appearance, sometimes with a triangular halo (as a reference to the Trinity), or with a papal tiara, specially in Northern Renaissance painting. In these depictions The Father may hold a globe or book. He is behind and above Christ on the Cross in the

The orb, or the globe of the world, is rarely shown with the other two persons of the Trinity and is almost exclusively restricted to God the Father, but is not a definite indicator since it is sometimes used in depictions of Christ. A book, although often depicted with the Father is not an indicator of the Father and is also used with Christ.[1]

From Renaissance to Baroque

Representations of God the Father and the Trinity were attacked both by Protestants and within Catholicism, by the

Artistic depictions of God the Father were uncontroversial in Catholic art thereafter, but less common depictions of the

God the Father appears in several Genesis scenes in

In both the Last Judgment and the Coronation of the Virgin paintings by

While representations of God the Father were growing in Italy, Spain, Germany and the Low Countries, there was resistance elsewhere in Europe, even during the 17th century. In 1632 most members of the

In 1667 the 43rd chapter of the Great Moscow Council specifically included a ban on a number of depictions of God the Father and the Holy Spirit, which then also resulted in a whole range of other icons being placed on the forbidden list,[30][31] mostly affecting Western-style depictions which had been gaining ground in Orthodox icons. The Council also declared that the person of the Trinity who was the "Ancient of Days" was Christ, as Logos, not God the Father. However some icons continued to be produced in Russia, as well as Greece, Romania, and other Orthodox countries.

Gallery of art

15th century

-

Pietà with God the Father and the dove of the Holy Spirit, Jean Malouel 1400-1410

-

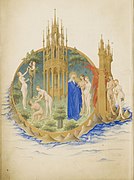

Limbourg Brothers, 1410–15, in the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry

-

Creation of Adam and Eve, Lorenzo Ghiberti, about 1425, Florence Baptistery

-

Giovanni d'Alemagna and Antonio Vivarini, c. 1443

-

Benvenuto di Giovanni, 1470

-

Pietro Perugino, Annunciation, 1489

-

Gottes Not, a GermanThrone of Mercy, Jan Polack, 1491

16th century

-

Lorenzo Costa, Crowning of the Virgin and saints, 1501

-

Fra Bartolomeo, 1509

-

Michelangelo, Creation of the Sun and Moon (detail), 1511

-

Creation of Adam, 1511

-

Albrecht Dürer, 1511

-

Titian's Assumption of Mary, 1516–1518

-

Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen, 16th century

-

Federico Barocci, Annunciation, 1592

17th century

-

Riva del Garda, Italy 1603-1636

-

RubensLast Judgment (detail) 1617

-

Crowning of the Virgin byRubens, early 17th century

-

José de Ribera, 1635

-

Giulio Cesare Procaccini, Coronation of the Virgin, 17th century

-

Bartholomeus Strobel, Poland, 1643

-

Velázquez, Crowning of the Virgin, 1645

-

Murillo, 1675-1682

18th-20th centuries

-

Holy Trinity Column in Olomouc, 1754

-

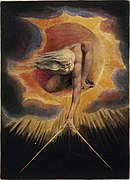

William Blake, Ancient of Days, 1794

-

Julius Schnorr, 1860

-

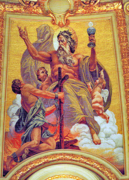

Anton von Werner, Berlin Cathedral, c. 1900

-

St. Francis's Church in Kraków, ca. 1900

-

Val Gardena, Italy, 1910

-

Mosaic in Serbian Orthodox Church, Serbia 1930s

-

First Vision, 1913, with God the Father on the right, and Jesus Christ on the left.

-

Los Angeles Cathedral, stained glassfrom the 1920s

See also

- Holy Spirit in Christian art

- Trinity in Christian art

Notes

- ^ ISBN 0-19-501432-4page 222

- ISBN 0-19-501432-4page 92

- ^ ISBN 0-8192-2345-Xpage 2

- ^ A matter disputed by some scholars

- ISBN 0-7661-4075-Xpages 167

- ISBN 0-7661-4075-Xpages 167-170

- ^ Dominique Thiébaut: "Enguerrand Quarton", Grove Art Online. Oxford University Press, 2007, [1]

- ^ Suggestion by F.W. Sclatter, see review by W. Eugene Kleinbauer of The Clash of Gods: A Reinterpretation of Early Christian Art, by Thomas F. Mathews, Speculum, Vol. 70, No. 4 (Oct., 1995), pp. 937-941, Medieval Academy of America, JSTOR

- ISBN 0-540-01085-5

- ISBN 1-879038-15-3page 27

- ^ According to accounts by Patriarch Nikephoros and the chronicler Theophanes

- ^ Warren Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society, Stanford University Press, 1997

- ISBN 0-679-60148-1page 1693

- ISBN 0-88141-245-7

- ISBN 1-879038-15-3page 29

- ISBN 0-8028-2888-4page 65

- ISBN 1-879038-15-3page 41

- ISBN 0-7661-4075-Xpages 169

- Arena Chapel, at the top of the triumphal arch, God sending out the angel of the Annunciation. See Schiller, I, fig 15

- ^ Bigham Chapter 7

- ISBN 1-4179-0870-Xpage 32

- ISBN 0-313-24658-0pages 8 and 283

- ^ Text of the 25th decree of the Council of Trent

- ^ Bigham, 73-76

- ISBN 0-8262-0796-0page 222

- ISBN 0-8020-3721-6page 233

- ISBN 1-103-66622-3, (2009) page 229

- ISBN 0559376871, 2006 page 156

- ISBN 1-103-66622-3, (2009) page 230

- ISBN 1-86189-118-0page 185

- ^ Orthodox church web site

Further reading

- Manuth, Volker. "Denomination and Iconography: The Choice of Subject Matter in the Biblical Painting of the Rembrandt Circle", Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art, vol. 22, no. 4, 1993, pp. 235–252., JSTOR

External links

- Age of spirituality : late antique and early Christian art, third to seventh century from The Metropolitan Museum of Art