Grey reef shark

| Grey reef shark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Subdivision: | Selachimorpha |

| Order: | Carcharhiniformes |

| Family: | Carcharhinidae |

| Genus: | Carcharhinus |

| Species: | C. amblyrhynchos

|

| Binomial name | |

| Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos (Bleeker, 1856)

| |

| |

| Range of the grey reef shark | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Carcharias amblyrhynchos Bleeker, 1856 | |

The grey reef shark or gray reef shark (Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos, sometimes misspelled amblyrhynchus or amblyrhinchos)

The grey reef shark is a fast-swimming, agile

connection. Litters of one to six pups are born every other year.The grey reef shark was the first shark species known to perform a

Taxonomy and phylogeny

Dutch

In older literature, the scientific name of this species was often given as C. menisorrah.

Description

The grey reef shark has a streamlined, moderately stout body with a long, blunt snout and large, round eyes. The upper and lower jaws each have 13 or 14 teeth (usually 14 in the upper and 13 in the lower). The upper teeth are triangular with slanted cusps, while the bottom teeth have narrower, erect cusps. The tooth serrations are larger in the upper jaw than in the lower. The first

The coloration is grey above, sometimes with a bronze sheen, and white below. The entire rear margin of the

Distribution and habitat

The grey reef shark is native to the

Generally a coastal, shallow-water species, grey reef sharks are mostly found in depths less than 60 m (200 ft).[11] However, they have been known to dive to 1,000 m (3,300 ft).[2] They are found over continental and insular shelves, preferring the leeward (away from the direction of the current) sides of coral reefs with clear water and rugged topography. They are frequently found near the drop-offs at the outer edges of the reef, particularly near reef channels with strong currents,[12] and less commonly within lagoons. On occasion, this shark may venture several kilometers out into the open ocean.[4][11]

Biology and ecology

Along with the

On the infrequent occasions when they swim in oceanic waters, grey reef sharks often associate with marine mammals or large pelagic fishes, such as sailfish (Istiophorus platypterus). One account has around 25 grey reef sharks following a large pod of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops sp.), along with 25 silky sharks (C. falciformis) and a single silvertip shark.[14] Rainbow runners (Elagatis bipinnulata) have been observed rubbing against grey reef sharks, using the sharks' rough skin to scrape off parasites.[15]

Grey reef sharks are themselves prey for larger sharks, such as the

Feeding

Grey reef sharks feed mainly on bony fishes, with

Life history

During mating, the male grey reef shark bites at the female's body or fins to hold onto her for

Behavior

Grey reef sharks are active at all times of the day, with activity levels peaking at night.

Little evidence of

Sociality

Social aggregation is well documented in grey reef sharks. In the northwestern Hawaiian Islands, large numbers of pregnant females have been observed slowly swimming in circles in shallow water, occasionally exposing their dorsal fins or backs. These groups last from 11:00 to 15:00, corresponding to peak daylight hours.[29] Similarly, at Sand Island off Johnston Atoll, females form aggregations in shallow water from March to June. The number of sharks per group differs from year to year. Each day, the sharks begin arriving at the aggregation area at 09:00, reaching a peak in numbers during the hottest part of the day in the afternoon, and dispersing by 19:00. Individual sharks return to the aggregation site every one to six days. These female sharks are speculated to be taking advantage of the warmer water to speed their growth or that of their embryos. The shallow waters may also enable them to avoid unwanted attention by males.[10]

Off Enewetak, grey reef sharks exhibit different social behaviors on different parts of the reef. Sharks tend to be solitary on shallower reefs and pinnacles. Near reef drop-offs, loose aggregations of five to 20 sharks form in the morning and grow in number throughout the day before dispersing at night. In level areas, sharks form polarized schools (all swimming in the same direction) of around 30 individuals near the sea bottom, arranging themselves parallel to each other or slowly swimming in circles. Most individuals within polarized schools are females, and the formation of these schools has been theorized to relate to mating or pupping.[26][27]

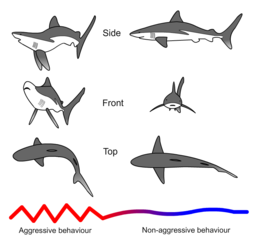

Threat display

The "hunch"

Most observed displays by grey reef sharks have been in response to a diver (or submersible) approaching and following it from a few meters behind and above. They also perform the display toward moray eels, and in one instance toward a much larger great hammerhead (which subsequently withdrew). However, they have never been seen performing threat displays toward each other. This suggests the display is primarily a response to potential threats (i.e. predators) rather than competitors. As grey reef sharks are not territorial, they are thought to be defending a critical volume of "personal space" around themselves. Compared to sharks from French Polynesia or Micronesia, grey reef sharks from the Indian Ocean and western Pacific are not as aggressive and less given to displaying.[3]

Human interactions

Grey reef sharks are often curious about divers when they first enter the water and may approach quite closely, though they lose interest on repeat dives.[4] They can become dangerous in the presence of food, and tend to be more aggressive if encountered in open water rather than on the reef.[14] There have been several known attacks on spearfishers, possibly by mistake, when the shark struck at the speared fish close to the diver. This species will also attack if pursued or cornered, and divers should immediately retreat (slowly and always facing the shark) if it begins to perform a threat display.[4] Photographing the display should not be attempted, as the flash from a camera is known to have incited at least one attack.[3] Although of modest size, they are capable of inflicting significant damage: during one study of the threat display, a grey reef shark attacked the researchers' submersible multiple times, leaving tooth marks in the plastic windows and biting off one of the propellers. The shark consistently launched its attacks from a distance of 6 m (20 ft), which it was able to cover in a third of a second.[15] As of 2008, the International Shark Attack File listed seven unprovoked and six provoked attacks (none of them fatal) attributable to this species.[30]

Although still abundant in pristine sites, grey reef sharks are susceptible to localized depletion due to their slow reproductive rate, specific habitat requirements, and tendency to stay within a certain area. The

References

- ^ doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T39365A173433550.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - ^ a b c d Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2009). "Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos" in FishBase. April 2009 version.

- ^ .

- ^ ISBN 978-92-5-101384-7.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8248-1808-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-2-8317-0700-6.

- ^ Garrick, J.A.F. (1982). Sharks of the genus Carcharhinus. NOAA Technical Report, NMFS Circ. 445.

- .

- ^ a b c d Bester, C. Biological Profiles: Grey Reef Shark Archived 2008-06-04 at the Wayback Machine. Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. Retrieved on April 29, 2009.

- ^ S2CID 46066734.

- ^ .

- ^ Dianne J. Bray, 2011, Grey Reef Shark, Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos, in Fishes of Australia, accessed 25 August 2014, http://www.fishesofaustralia.net.au/Home/species/2881 Archived 2014-12-15 at the Wayback Machine

- S2CID 245303571.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-900724-28-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8117-2875-1.

- ISBN 978-0-618-19716-3.

- S2CID 915034.

- ^ Newbound, D.R.; Knott, B. (1999). "Parasitic copepods from pelagic sharks in Western Australia". Bulletin of Marine Science. 65 (3): 715–724.

- S2CID 8645018.

- PMID 18605791.

- ^ .

- ^ "Gombessa IV expedition". Archived from the original on 2020-06-11. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

- ^ Gombessa IV on arte.tv (archive.org)

- ISBN 978-0-8493-7139-4.

- ^ Robbins, W.D. (2006). Abundance, demography and population structure of the grey reef shark (Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos) and the white tip reef shark (Triaenodon obesus) (Fam. Charcharhinidae). PhD thesis, James Cook University.

- ^ a b c Martin, R.A. Coral Reefs: Grey Reef Shark. ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Retrieved on April 30, 2009.

- ^ a b McKibben J.N.; Nelson, D.R. (1986). "Pattern of movement and grouping of gray reef sharks, Carcharhinus amblyrhyncos, at Enewetak, Marshall Islands". Bulletin of Marine Science. 38: 89–110.

- ^ a b Nelson, D.R. (1981). "Aggression in sharks: is the grey reef shark different?". Oceanus. 24: 45–56.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8248-1562-2.

- ^ ISAF Statistics on Attacking Species of Shark. International Shark Attack File, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida. Retrieved on May 1, 2009.

- ^ Anderson, R.C.; Sheppard, C.; Spalding, M. & Crosby, R. (1998). "Shortage of sharks at Chagos". Shark News. 10: 1–3.

- PMID 17141612.

External links

- "Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos, Grey reef shark" at FishBase

- "Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos (Grey Reef Shark)" at IUCN Red List

- "Biological Profiles: Grey reef shark" at Florida Museum of Natural History Archived 2008-06-04 at the Wayback Machine

- "Coral Reefs: Grey Reef Shark" at ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research

- "Species description of Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos" at Shark-References.com

- Photos of Grey reef shark on Sealife Collection