History of Baltimore

| History of Maryland |

|---|

|

|

This article describes the history of the

Native American settlement

The Baltimore area had been inhabited by

In the early 17th century, the immediate Baltimore vicinity was populated by

In 1608, Captain John Smith traveled 210 mi (340 km) from Jamestown to the uppermost Chesapeake Bay, leading the first European expedition to the Patapsco River, a word used by the Algonquin language natives who fished shellfish and hunted[7] The name "Patapsco" is derived from pota-psk-ut, which translates to "backwater" or "tide covered with froth" in Algonquian dialect.[8] A quarter-century after John Smith's voyage, Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore led 140 colonists on the merchantman The Ark to settle in North America. The colonists were initially frightened by the Piscataway in southern Maryland because of their body paint and war regalia, incorrectly assuming they wished to attack the fledgling colonial settlement. However, the chief of the Piscataway tribe was quick to grant the colonists permission to settle within Piscataway territory and cordial relations were established between them and the Piscataway.[9]

European settlement

The

Another "Baltimore" existed on the Bush River as early as 1674. That first county seat of Baltimore County is known today as "Old Baltimore". It was located on the Bush River on land that in 1773 became part of Harford County. In 1674, the General Assembly passed "An Act for erecting a Court-house and Prison in each County within this Province."[10] The site of the courthouse and jail for Baltimore County was evidently "Old Baltimore" near the Bush River. In 1683, the General Assembly passed "An Act for Advancement of Trade" to "establish towns, ports, and places of trade, within the province."[11] One of the towns established by the act in Baltimore County was "on Bush River, on Town Land, near the Court-House." The courthouse on the Bush River referenced in the 1683 Act was in all likelihood the one created by the 1674 Act. "Old Baltimore" was in existence as early as 1674, but we don't know with certainty what if anything happened on the site prior to that year. The exact location of Old Baltimore was lost for years. It was certain that the location was somewhere on the site of the present-day Aberdeen Proving Ground (APG), a U.S. Army testing facility. in the 1990s, APG's Cultural Resource Management Program took up the task of finding Old Baltimore. The firm of R. Christopher Goodwin & Associates was contracted for the project. After Goodwin first performed historical and archival work, they coordinated their work with existing landscape features to locate the site of Old Baltimore. APG's Explosive Ordnance Disposal personnel went in with Goodwin to defuse any unexploded ordnance. Working in 1997 and 1998, the field team uncovered building foundations, trash pits, faunal remains, and 17,000 artifacts, largely from the 17th century.[12][13] The Bush River proved to be an unfortunate location because the port became silted and impassable to ships, forcing the port facilities to relocate.[14] By the time Baltimore on the Patapsco River was established in 1729, Old Baltimore Town had faded away.[15]

Maryland's colonial General Assembly created and authorized the

The city is named after

Also around the Basin to the southeast along the southern peninsula which ended at Whetstone Point—today South Baltimore, Federal Hill, and Locust Point—the funding for new wharves and slips came from individual wealthy ship-owners and brokers and from the public authorities through the town commissioners by means of lotteries, for the tobacco trade and shipping of other raw materials overseas to the Mother Country, for receiving manufactured goods from England, and for trade with other ports being established up and down the Chesapeake Bay and in the other burgeoning colonies along the Atlantic coast.

Early development of Baltimore Town: 1729–1796

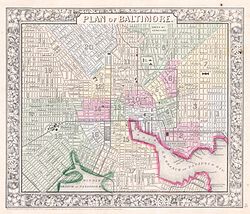

The Maryland General Assembly established the Town of Baltimore in 1729. Unlike many other towns established around that time, Baltimore was more than just existence on paper.

The first printing press was introduced to the city in 1765 by a German immigrant,

Throughout the 18th Century, Baltimore drained and filled in marshes (notably Thomas "Harrison's Marsh" along the Jones Falls west bank), built canals around the falls and through the center of town, built bridges across the Falls and annexed neighboring

During the American Revolution, the Second Continental Congress temporarily fled from Philadelphia and held sessions in Baltimore between December 1776 and February 1777. When the Continental Congress authorized the privateering of British merchantmen, eager Baltimore merchants accepted the challenge, and as the war progressed, the shipbuilding industry expanded and boomed. There was no major military action near the city though, except for the passing nearby and a feint towards the town by a Royal Navy fleet as they headed north up the Chesapeake Bay to land an army at Head of Elk in the northeast corner to march on the American capital at Philadelphia and the following battles at Brandywine and Germantown.

The American Revolution stimulated the domestic market for wheat and iron ore, and in Baltimore, flour milling increased along the Jones and Gwynns Falls. Iron ore transport greatly boosted the local economy. The British naval blockade hurt Baltimore's shipping, but also freed merchants and traders from British debts, which along with the capture of British merchant vessels furthered Baltimore's economic growth. By 1800 Baltimore had become one of the major cities of the new republic.[25]

The economic foundations laid down between 1763 and 1776 were vital to the even greater expansion seen during the Revolutionary War. Though still lagging behind Philadelphia, Baltimore merchants and entrepreneurs produced an expanding commercial community with family businesses and partnerships proliferating in shipping, the flour-milling and grain business, and the indentured servant traffic. International trade focused on four areas: Britain, Southern Europe, the West Indies, and the North American coastal towns. Credit was the essence of the system and a virtual chain of indebtedness meant that bills remained long unpaid and little cash was used among overseas correspondents, merchant wholesalers, and retail customers. Bills of exchange were used extensively, often circulating as currency. Frequent crises of credit and the wars with France kept prices and markets in constant flux, but men such as William Lux and the Christie brothers produced a maturing economy and a thriving metropolis by the 1770s.[26]

The population reached 14,000 in 1790, but the decade was a rough one for the city. The Bank of England's suspension of specie payments caused the network of Atlantic credit to unravel, leading to a mild recession. The Quasi-War with France in 1798-1800 caused major disruptions to Baltimore's trade in the Caribbean. Finally, a yellow fever epidemic diverted ships from the port, while much of the urban population fled into the countryside. The downturn widened to include every social class and area of economic activity. In response, the business community diversified away from an economy based heavily on foreign trade.[27]

Baltimore City before the Civil War: 1797–1861

| Year | 1790 | 1800 | 1810 | 1820 | 1830 | 1840 | 1850 | 1860 | 1870 | 1880 | 1890 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 14,000 | 27,000 | 47,000 | 63,000 | 81,000 | 102,000 | 169,000 | 212,000 | 267,000 | 332,000 | 434,000 |

In 1797, Baltimore Town merged with Fells Point and incorporated as the City of Baltimore. Baltimore grew rapidly, becoming the largest city in the Southern United States. It dominated the American flour trade after 1800 due to the milling technology of Oliver Evans, the introduction of steam power in processing, and the merchant-millers' development of drying processes which greatly slowed spoilage. Still, by 1830 New York City's competition was felt keenly, and Baltimoreans were hard-pressed to match the merchantability standards despite more rigorous inspection controls than earlier, nor could they match the greater financial resources of their northern rivals.

The city was the site of the Battle of Baltimore during the War of 1812. After burning Washington, D.C., the British attacked Baltimore outside the eastern outskirts of town on the "Patapsco Neck" on September 12, at the Battle of North Point, then on the night of September 13–14, 1814. United States forces from Fort McHenry successfully defended the city's harbor from the British.

In the wake of the War of 1812, residents expected the city to become America's leading cultural and commercial center and the literary community dubbed their city "the Rome of the United States".[28] The number of Baltimore printers, publishers, and booksellers had doubled in the preceding years.[29] Between 1816 and 1825, Baltimore's literary focal point was the Delphian Club.[30][31] Twelve newspapers had editors in the Club and the club's sixteen members published at least 48 books of fiction, history, travel, letters, and biography, as well as nine volumes of poetry, one play, and nineteen speeches. The club's organ was The Portico literary magazine.[32]

A distinctive local culture started to take shape, and a unique skyline peppered with churches and monuments developed. Baltimore acquired its moniker "The Monumental City" after an 1827 visit to Baltimore by President John Quincy Adams. At an evening function, Adams gave the following toast: "Baltimore: the Monumental City—May the days of her safety be as prosperous and happy, as the days of her dangers have been trying and triumphant."[33]

Finance

Baltimore & Ohio Railroad established

Baltimore faced economic stagnation unless it opened routes to the western states, as

Following the B&O's start of regular operations in 1830, other railroads were built in the city.

The

Free and enslaved labor

From the late 18th century into the 1820s Baltimore was a "city of transients," a fast-growing boom town attracting thousands of ex-slaves from the surrounding countryside. Slavery in Maryland declined steadily after the 1810s as the state's economy shifted away from plantation agriculture, as evangelicalism and a liberal

The Maryland Chemical Works of Baltimore used a mix of free labor, hired slave labor, and enslaved people held by the corporation to work in its factory.[41] Since chemicals needed constant attention, the rapid turnover of free white labor encouraged the owner to use enslaved workers. While slave labor was about 20 percent cheaper, the company began to reduce its dependence on enslaved labor in 1829 when two slaves ran away and one died.[42]

The location of Baltimore in a border state created opportunities for enslaved people in the city to run away and find freedom in the north—as Frederick Douglass did. Therefore, slaveholders in Baltimore frequently turned to gradual manumission as a means to secure dependable and productive labor from slaves. In promising freedom after a fixed period of years, slaveholders intended to reduce the costs associated with lifetime servitude while providing slaves incentive for cooperation. Enslaved people tried to negotiate terms of manumission that were more advantageous, and the implicit threat of flight weighed significantly in slaveholders' calculations. The dramatic decrease in the enslaved population during 1850-60 indicates that slavery was no longer profitable in the city. Slaves were still used as expensive house servants: it was cheaper to hire a free worker by the day, with the option of dropping him or replacing him with a better worker, rather than run the expense of maintaining a slave month in and month out with little flexibility.[43]

On the eve of the Civil War, Baltimore had the largest free black community in the nation. About 15 schools for black people were operating, including Sabbath schools operated by Methodists, Presbyterians, and Quakers, along with several private academies. All black schools were self-sustaining, receiving no state or local government funds, and whites in Baltimore generally opposed educating the black population, continuing to tax black property holders to maintain schools from which black children were excluded by law. Baltimore's black community, nevertheless, was one of the largest and most divided in America due to this experience.[44]

Know-Nothing Party and Baltimore politics

Baltimore in the

Baltimore during and after the Civil War: 1861–1894

Baltimore plot

Because of fear of assassination while passing through Baltimore on the way to

Civil War

The Civil War divided Baltimore and Maryland's residents. Much of the social and political elite favored the Confederacy—and indeed owned house slaves. In the 1860 election the city's large German element voted not for Lincoln but for Southern Democrat John C. Breckinridge. They were less concerned with the abolition of slavery, an issue emphasized by Republicans, and much more with nativism, temperance, and religious beliefs, associated with the Know-Nothing Party and strongly opposed by the Democrats. However the Germans hated slavery and supported the Union.[46]

When

When Massachusetts troops marched through the city on April 19, 1861, en route to

African Americans after the Civil War

Maryland was not subject to

Baltimore had a larger population of African Americans than any northern city. The new Maryland state constitution of 1864 ended slavery and provided for the education of all children, including blacks. The Baltimore Association for the Moral and Educational Improvement of the Colored People established schools for blacks that were taken over by the public school system, which then restricted education for blacks beginning in 1867 when Democrats regained control of the city. Establishing an unequal system that prepared white students for citizenship while using education to reinforce black subjugation, Baltimore's postwar school system exposed the contradictions of race, education, and republicanism in an age when African Americans struggled to realize the ostensible freedoms gained by emancipation.[49] Thus blacks found themselves forced to support Jim Crow legislation and urged that the "colored schools" be staffed only with black teachers. From 1867 to 1900 black schools grew from 10 to 27 and enrollment from 901 to 9,383. The Mechanical and Industrial Association achieved success only in 1892 with the opening of the Colored Manual Training School. Black leaders were convinced by the Rev. William Alexander and his newspaper, the Afro American, that economic advancement and first-class citizenship depended on equal access to schools.[44]

Economic growth

By 1880 manufacturing replaced trade and made the city a nationally important industrial center. The port continued to ship increasing amounts of grain, flour, tobacco, and raw cotton to Europe. The new industries of men's clothing, canning, tin and sheet-iron ware products, foundry and machine shop products, cars, and tobacco manufacture had the largest labor force and largest product value.[50]

The construction of new housing was a major factor in Baltimore's economy. Vill (1986) examines the activities of major builders between 1869 and 1896, especially as they gained access to building land and capital. Most, but not all, of the major builders were craftsmen who were entrepreneurs compared with others in the building trades, but were still small businessmen who built small numbers of houses during long careers. They worked with landowners, and both groups manipulated the city's leasehold system to their own advantage. Builders obtained credit from a diverse array of sources, including sellers of land, building societies, and land companies. The most important source was individual lenders, who lent money in small amounts either on their own account or through lawyers and trustees overseeing funds held in trust. In spite of their important role in shaping the city, the contractors were small businessmen who rarely achieved citywide visibility.[51] Until the 1890s, Baltimore remained a patchwork of nationalities with white natives, German and Irish immigrants, and black Baltimoreans scattered throughout the 'social quilt' in heterogeneous neighborhoods.

Baltimore was the origin of a major railroad workers' strike in 1877 when the B&O company attempted to lower wages. On July 20, 1877, Maryland Governor John Lee Carroll called up the 5th and 6th Regiments of the National Guard to end the strikes, which had disrupted train service at Cumberland in western Maryland. Citizens sympathetic to the railroad workers attacked the National Guard troops as they marched from their armories in Baltimore to Camden Station. Soldiers from the 6th Regiment fired on the crowd, killing 10 and wounding 25. Rioters then damaged B&O trains and burned portions of the rail station. Order was restored in the city on July 21–22 when federal troops arrived to protect railroad property and end the strike.

YWCA

An expanded economic activity brought many immigrants from the countryside and from Europe after the Civil War. Concerns for young, single Protestant women alone in cities led to the growth of the

Progressive Era: 1895–1928

| Year | 1900 | 1910 | 1920 | 1930 | 1940 | 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1980 | 1990 | 2000 | 2007 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 509,000 | 558,000 | 734,000 | 805,000 | 859,000 | 950,000 | 939,000 | 906,000 | 787,000 | 736,000 | 651,000 | 637,000 |

Political reform began in the mid-1890s with the defeat of the

Women's rights

Founded in 1894,

The Great Baltimore Fire

The

Park planning

The story of the Patapsco Forest Reserve (later renamed the Patapsco Valley State Park) near Baltimore reveals notable connections between the Progressive-era movements for forest conservation and urban park planning. In 1903, the Patapsco Valley site, although outside the city boundary, was nevertheless identified by the Olmstead Brothers landscape architecture firm as an ideal site to acquire property for future park development. At the same time, the Maryland State Board of Forestry, seeking to establish scientific forestry research, received donated land for this purpose in the Patapsco Valley. Over subsequent decades, a powerful alliance of urban elites, state managers, and city officials assembled thousands of acres along the Patapsco River. The site evolved into a unique hybrid of forest preserve and public park that reflected both its location on the urban fringe and its dual heritage in the conservation and parks movements.[61]

Baseball

When in 1918 the US government reversed its draft exemption for married workers and required all men to work in essential occupations or serve in the military, professional baseball players either enlisted or joined industrial baseball leagues. Company leagues included those of Bethlehem Steel, which had recreational leagues on both coasts that by 1918 represented a major-league level of competition. Sparrows Point, Maryland, a Bethlehem Steel company town, had a Steel League team, whose results Baltimore baseball fans followed closely. At the same time, fans also followed the draft status and 1918 season of Baltimore native Babe Ruth, then playing with the Boston Red Sox and considering his own options, including joining an industrial league team. In September Bethlehem Steel, fearing competition with other leagues over professional talent, disbanded the Steel League. When the war ended in November, players such as Ruth were free to re-sign with their major league teams.[62]

Residential segregation

With the upswell of urbanization and industrialization, Baltimore experienced a boom in population, with its African American population growing from 54,000 to 79,000 between 1880 and 1900 and its total population more than doubling from 250,000 to 509,000 between 1870 and 1900.[63] At the turn of the century, Baltimore citizens were also grappling with the escalation of disease and economic depression. African Americans moving from the South and rural areas with little money and limited job opportunities compromised living conditions by seeking cheaper housing and sharing apartments designed for single-families across multiple large families. This influx of residents into neighborhoods with poor sanitation and structural integrity began the formation of Baltimore's first slums.

Throughout the nineteenth century, Baltimore citizens had experienced no legislation segregating their housing. However, white residents became hostile towards black citizens moving from rural areas and the Baltimore slums into predominantly white neighborhoods, leading lawyer Milton Dashiell to draft an ordinance to segregate Baltimore. In 1911, Mayor J. Barry Mahool passed Dasheill's bill into law, cementing Baltimore as the first U.S. city to pass a residential segregation ordinance that constrained where African Americans could live. The law prohibited people of color from moving onto blocks where whites were the majority, and prevented white people from moving onto blocks where people of color were the majority. Many other cities across the United States soon followed suit, passing their own residential segregation laws. The supreme court struck down the 1917 Louisville, Kentucky ordinance, repealing Baltimore's segregation ordinance, but the legacy of the ordinance remained.[64]

Although Baltimore had experienced an influx in its African American population around the turn of the century, the start of the First World War and the increased availability of urban industry jobs spurred the Great Migration, leading Baltimore like other Northern cities to experience a surge in its African American population, particularly around its ports. In response to the 1917 supreme court decision that abolished residential segregation and the influx of African American migrants, Mayor James H. Preston ordered housing inspectors to report anyone who rented or sold property to black people in predominantly white neighborhoods.[65] This order entrenched the geographical divide by race in Baltimore, laying the redline foundations in the city. Twenty years later, Baltimore's housing projects were racially segregated into "white housing" and "Negro housing", further discriminating the distribution of Baltimore's resources.

Depression and War: 1929–1949

Argersinger (1988) describes the loss of power by traditional Democratic leaders and organizations in Baltimore under the New Deal. The old-line Democrats operated in the spirit of traditional political bosses who dispensed the patronage. They were, at best, lukewarm Roosevelt supporters because the New Deal threatened their monopoly on patronage. Blacks, other ethnic groups, labor, and other former supporters turned from their patrons to other leadership. Baltimore Mayor Howard W. Jackson's support gradually eroded until he was defeated in a gubernatorial primary election to choose an opponent for a Republican who earlier defeated Governor Albert C. Richie, a conservative Democrat.[66]

World War II

Baltimore was a major war production center in

Father John F. Cronin's early confrontations with Communists in the World War II-era labor movement turned him into a leading anti-Communist in the Catholic Church and the US government during the Cold War. Father Cronin, then a prominent Catholic parish priest, saw a united labor movement as central to his moderate, reformist vision for Baltimore's social ills, and worked closely with anti-Communist labor leaders.[68]

Cold War era

In 1950, the city's population topped out at 950,000 people, of whom 24 percent were black. Then the white movement to the suburbs began in earnest, and the population inside the city limits steadily declined and became proportionately more black.

Schools

Integration of Baltimore's public schools at first went smoothly, as city elites suppressed working-class white complaints, as white families migrated to suburban school systems. By the 1970s new problems had surfaced. Formerly white schools had become mostly black schools, though whites still made up most of the faculty and administration. Worse, the school system had become dependent on federal funding. In 1974, these circumstances led to two dramatic incidents. A teachers' strike highlighted the city's unwillingness to raise teachers' salaries because a hike in property taxes would further alienate white residents. A second crisis revolved around a federally mandated desegregation plan that also threatened to alienate the remaining white residents.

Drugs

Heroin supply and use in Baltimore rose explosively in the 1960s, following a trend of rising drug use across the United States. In the late 1940s, there were only a few dozen African-American heroin addicts in the Pennsylvania Avenue area of the city. Heroin use began largely for reasons of prestige within a group that most middle-class blacks looked down on. When the Baltimore police formed the three-man narcotics squad in 1951 there was only moderate profit in drug dealing and shoplifting was the addict's crime of choice. By the late 1950s, young whites were using the drug, and by 1960 there were over one thousand heroin addicts in the police files; this figure doubled in the 1960s. A generation of profiteering young, violent black dealers took over in the 1960s as violence increased and the price of heroin skyrocketed. Increasing drug usage was the primary reason for burglaries rising tenfold and robberies rising thirtyfold from 1950 to 1970. Soaring numbers of broken homes and Baltimore's declining economic status probably exacerbated the drug problem. Adolescents in suburban areas began using drugs in the late 1960s.[69]

Civil rights

In the 1930s and 1940s, the local chapter of the

Read's Drug Store in Baltimore was the site of one of the nation's earliest sit-ins in January 1955. When a handful of black students sat at the store's lunch counter for less than half an hour, it precipitated a wave of desegregation.[70][71]

In the late 1950s Martin Luther King Jr. and his national civil rights movement inspired black ministers in Baltimore to mobilize their communities in opposition to local discrimination. The churches were instrumental in keeping lines of communication open between the geographically and politically divided middle-class and poor blacks, a chasm that had widened since the end of World War II. Ministers formed a network across churches and denominations and did much of the face-to-face work of motivating people to organize and protest. In many cases they also adopted King's theology of justice and freedom and altered their preaching styles.[72]

Civil rights activists also adopted more radical positions in the late 1960s. For example, Walter Lively, a socialist community activist, worked with and helped found several Black organizations devoted to racial and class equality and developed his own printing house and community museum.

1968 unrest

Unrest in the black inner-city exploded for four nights in April 1968, after news arrived of the assassination of the Reverend

Backlash

In the 1950s and 1960s, racial politics intensified in Baltimore, as in other cities. White Southerners came to Baltimore for factory jobs during World War II, permanently altering the city's political landscape. The new arrivals approved of the segregated system that had been in effect since the early 20th century. Working whites mobilized to prevent school integration after the Brown v. Board of Education decision of the Supreme Court in 1954. They believed that their interests were being sacrificed to those of black Americans. As working-class whites began to feel increasingly embattled in the face of federal intervention into local practices, many turned to the 1964 presidential primary campaign of George Wallace who swept the white working-class vote. Durr (2003) explains the defection of white working-class voters in Baltimore to the Republican Party as being caused by their fears that the Democratic Party's desegregation policies posed a threat to their families, workplaces, and neighborhoods.[76]

Between 1950 and 1990, Baltimore's population declined by more than 200,000. The center of gravity has since shifted away from manufacturing and trade to service and knowledge industries, such as medicine and finance. Gentrification by well-educated newcomers has transformed the Harbor area into an upscale tourist destination.[77]

21st century

In January 2004, the historic Hippodrome Theatre reopened after significant renovation as part of the France-Merrick Performing Arts Center.[78] The Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History & Culture opened in 2005 on the northeast corner of President Street and East Pratt Street, and the National Slavic Museum in Fell's Point was established in 2012. On April 12, 2012, Johns Hopkins held a dedication ceremony to mark the completion of one of the United States' largest medical complexes – the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore – which features the Sheikh Zayed Cardiovascular and Critical Care Tower and The Charlotte R. Bloomberg Children's Center. The event, held at the entrance to the $1.1 billion 1.6 million-square-foot-facility, honored the many donors including Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan, first president of the United Arab Emirates, and Michael Bloomberg.[79][80]

Maryland's Star-Spangled 200 celebration, launched as the "Star-Spangled Sailabration" and crescendo "Star-Spangled Spectacular" festivals, was a three-year commemoration of the 200th anniversary of the War of 1812 and the penning of The Star-Spangled Banner. The Star-Spangled Sailabration festival brought a total of 45 tall ships, naval vessels and others from the US, United Kingdom, Canada, Colombia, Brazil, Ecuador, and Mexico to Baltimore's Harbor. The event, held June 13–19, 2012, was the week encompassing Flag Day and the 200th anniversary of the Declaration of War.[81][82] The Star-Spangled Spectacular was a 10-day free festival that celebrated the 200th anniversary of the United States National Anthem from September 6–16, 2014. More than 30 naval vessels and tall ships from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, Norway, Germany, Spain, and Turkey berthed at the Inner Harbor, Fell's Point and North Locust Point. An air show from the Navy's Flight Demonstration Team, the Blue Angels performed during both festivals. Special guests such as President Barack Obama, Vice President Joe Biden, and Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus, were in attendance at Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine.[83] During the course of the Star-Spangled 200 celebration the city was showcased on three separate live television broadcasts. Visit Baltimore CEO, Tom Noonan, was quoted in the Baltimore Sun as calling the Spectacular, "the largest tourism event in our city's history." Over a million people visited Baltimore during both festivals.[84]

2015 protests

On April 19, 2015, West Baltimore resident Freddie Gray died after being in a coma for a week. Gray, who had a record of arrests for petty criminal activity, had been taken into custody after running from police. Gray suffered spinal injuries while in police custody and fell into the coma. The cause of his injuries was disputed, with some claiming they were accidental, while others claiming they were the result of police brutality.

Protests were initially nonviolent, with thousands of peaceful protesters filled the City Hall square. Protests against police brutality turned violent following Gray's funeral on April 27, as people burned police cruisers and buildings and damaged shops. The Governor of Maryland, Larry Hogan sent in the National Guard and imposed a curfew.[85] Six police officers were charged with crimes relating to Gray's death. One was acquitted, one trial ended in a hung jury, and four cases are ongoing as of June 12, 2016.[citation needed]

Port Covington development

On September 19, 2016, the Baltimore City Council approved a $660 million bond deal for the $5.5 billion

Francis Scott Key Bridge collapse

On March 26, 2024 at 1:28 am, the Francis Scott Key Bridge that connects sections of the Baltimore Metropolitan Area was struck by a container ship bound for Singapore, causing the bridge to collapse and killing at least 6 people who were doing construction work on the bridge.[90]

Religious history

Roman Catholics

Baltimore has long been a major center of the Catholic Church. Important bishops include

In 1806–21 Catholics constructed the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, based on a neoclassical design by architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe. The church completed a $34 million restoration based on Latrobe's original plans in 2006.

During 1948–61, the Archdiocese of Baltimore was under the leadership of Francis Patrick Keough. The Baltimore Church identified with the anti-Communist and anti-pornography movements and with the expansion of Catholic institutions that addressed a myriad of social, economic, and educational issues. The Church also coordinated a multitude of action projects under the financial control of the Baltimore chancery.[91]

Methodists

The Methodists were well received in Maryland in the 1760-1840 era, and Baltimore became an important center.[92] Sutton (1998) looks at Methodist artisans and craftsmen, showing they embraced an evangelical identity, Protestant ethic, and complex organizational structure. This enabled them to express their anti-elitist or populist "producerist" values of self-discipline, honesty, frugality, and industry; they denounced greed and sought an interdependent common good. Such producerist views drew on aspects of the Wesleyan ethic, appropriated the commonweal traditions of 18th-century republicanism, and initially resisted those of classical liberal, individualistic, self-interested capitalism. They also accorded well with and helped produce the emerging amalgam of American populist, restorationist, biblicistic, revivalistic activism that Sutton terms "Arminianized Calvinism."[93]

Inside the Methodist Church, the artisans were reformers who focused on three substantive and symbolic targets, each of which would democratize Methodist conferences: lay suffrage and representation; inclusion of the local preachers, who constituted two-thirds of Methodist leadership; and election of the officers who carried the administrative, personnel, and supervisory power, the presiding elders. The appeals made on behalf of these democratizations, Sutton shows, drew imaginatively on both producerist and Wesleyan rhetoric. By the 1850s, Sutton (1998) shows that the corporate ideals and individual disciplines of religious producerism were expressed in trade unionism, in evangelical missions to workers, in factory preaching, in workers' congregations, in temperance and Sabbatarianism, in the Sunday school movement, and in the politics of Protestant communal hegemony.[93]

Baptists

The Appalachians and southern whites arriving in the 1940s brought along a strong religious tradition with them. Southern Baptist churches multiplied during the mid and late 1940s.[94]

Evangelical Lutherans

The Zion Evangelical Lutheran congregation was founded in 1755 in order to serve the needs of Lutheran immigrants from Germany, as well as Germans from Pennsylvania who moved to Baltimore. It has a bi-lingual congregation that provides sermons in both German and English. In 1762 the congregation built its first church on Fish Street (now East Saratoga Street). It was replaced by a bigger building, the current Zion Church on North Gay Street and East Lexington Street erected from 1807 to 1808. An addition to the west along Lexington Street to Holliday Street of an "Aldersaal" (parish house), bell tower, parsonage, and enclosed garden in North German Hanseatic architecture under Pastor Julius K. Hoffman was made in 1912–1913.

Jews

Although the extent of Baltimore Jewry in the 18th century is not known, the existence of a Jewish cemetery in Baltimore can be traced back to 1786. The Jewish community grew significantly in the 19th century forming synagogues including Nidche Yisroel (now the

Muslims

Baltimore has had a Muslim community as far back as 1943. Masjid Ul-Haqq was established as a Nation of Islam mosque in 1947, on Ensor Street. The congregation later moved to 1000 Pennsylvania Avenue. The mosque was known as Mosque Six. The mosque moved to 514 Wilson Street in the late 1950s, where it is currently located. Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad spoke at the mosque in 1960 to over a thousand people. After the death of Muhammad in 1975, the mosque's congregants converted to Sunni Islam and it became known as Masjid Ul-Haqq.[96][97]

In 1979, the number of Muslims in Baltimore and its suburbs was estimated to be 3,000–5,000 by Islamic Society of Baltimore co-founder Dr. Mohamed Z. Awad.[98]

As reported by The Baltimore Sun, in 1983, the number of Muslims in Baltimore was estimated to be several thousand.[99] In 1985, the number was estimated the number to be around 15,000, as well as 40,000 Muslims living in the Baltimore–Washington region.[100]

In 1995, Maqbool Patel, the president of the Islamic Society of Baltimore, estimated the number of active Muslim families in the state to be 5,000, with 1,500 being in the Baltimore area.[101]

See also

- History of Native Americans in Baltimore

- History of African Americans in Baltimore

- History of the Germans in Baltimore

- History of slavery in Maryland

- Islam in Maryland

- Timeline of Baltimore

- List of mayors of Baltimore

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Baltimore, Maryland

Baltimore portal

Baltimore portal

References

- OCLC 18473413.

- ISBN 0-8139-1422-1. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- ^ Youssi, Adam (2006). "The Susquehannocks' Prosperity & Early European Contact". Historical Society of Baltimore County. Retrieved 2015-04-28.

- ^ Alex J. Flick; et al. (2012). "A Place Now Known Unto Them: The Search for Zekiah Fort" (PDF). St. Mary's College of Maryland. p. 11. Retrieved 2015-04-28.

- ISBN 978-0-313-38126-3. Retrieved 2015-04-28.

- Susquehannockshad reduced...the Piscataway 'empire'...to a belt bordering the Potomac south of the falls and extending up the principal tributaries. Roughly, the 'empire' covered the southern half of present Prince Georges County and all, or nearly all, of Charles County."

- ^ A Point of Natural Origin Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine and Locust Point – Celebrating 300 Years of a Historic Community Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine, Scott Sheads, Mylocustpoint.

- ^ "Ghosts of industrial heyday still haunt Baltimore's harbor, creeks". Chesapeake Bay Journal. Retrieved 2012-09-08.

- ISBN 978-0-313-38126-3. Retrieved October 10, 2012.

- ^ Bacon, Thomas (1765). Laws of Maryland At Large, with Proper Indexes. Vol. 75. Annapolis: Jonas Green. p. 61.

- ^ Bacon, Thomas (1765). Laws of Maryland At Large, with Proper Indexes. Vol. 75. Annapolis: Jonas Green. p. 70.

- ^ Blick, David G. (1999). "Aberdeen Proving Ground Uncovers 17th-century Settlement of "Old Baltimore"" (PDF). Cultural Resource Management. 22 (5). U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Cultural Resources: 42–44.

- . tDAR id: 392044. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ^ Childers, Linda (April 18, 2011). "SIGN: Site of "Old Baltimore"". Aberdeen Patch. Patch Media. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ^ Charlotte and "Doc" Cronin (September 19, 2014). "Remembering Old Baltimore when it was near Aberdeen". The Baltimore Sun.

- ^ Baltimore City, Maryland: Historical Chronology, Maryland State Archives, February 29, 2016, retrieved April 11, 2016

- ^ Calvert Family Tree (PDF), University Libraries, University of Maryland, retrieved April 11, 2016

- ^ Maryland History Timeline, Maryland Office of Tourism, retrieved April 11, 2016

- ^ Egan, Casey (November 23, 2015), "The surprising Irish origins of Baltimore, Maryland", IrishCentral, retrieved April 11, 2016

- ISBN 0-8018-7963-9.

- ^ "Significant dates in Baltimore's immigration history". Baltimore Immigration Memorial Foundation. Archived from the original on 2013-01-11. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- ^ Thomas, 1874, p. 323

- ^ Wroth, 1938, p. 41

- ^ Wroth, 1922, p. 114

- ^ Garrett Power, "Parceling out Land in the Vicinity of Baltimore: 1632-1796, Part 2," Maryland Historical Magazine 1993 88(2): 150-180,

- ^ Paul K. Walker, "Business and Commerce in Baltimore on the Eve of Independence," Maryland Historical Magazine 1976 71(3): 296-309,

- ^ Richard S. Chew, "Certain Victims of an International Contagion: The Panic of 1797 and the Hard Times of the Late 1790s in Baltimore," Journal of the Early Republic 2005 25(4): 565-613

- JSTOR 1916907.

- ISBN 978-0-674-00236-4.

- JSTOR 1916907.

- ^ Uhler, John Earle (December 1925). "The Delphian Club: A Contribution to the Literary History of Baltimore in the Early Nineteenth Century". Maryland Historical Magazine. 20 (4): 305.

- ^ Uhler, John Earle (December 1925). "The Delphian Club: A Contribution to the Literary History of Baltimore in the Early Nineteenth Century". Maryland Historical Magazine. 20 (4): 307–308.

- Salem Gazette. Salem, Massachusetts. October 23, 1827. p. 2. Retrieved October 27, 2008 – via NewsBank.

- ^ Gary L. Browne, "Business Innovation and Social Change: the Career of Alexander Brown after the War of 1812," Maryland Historical Magazine 1974 69(3): 243-255.

- ISBN 978-0226720258.

- ISBN 978-0-8047-2629-0.

- ^ ISBN 0-934118-22-1.

- ISBN 978-0-486-23818-0.

- OCLC 26302871.

- ^ Christopher Phillips Freedom's Port: The African American Community of Baltimore, 1791-1860 (1997)

- ^ Rice, Laura. Maryland History In Prints 1743-1900. p. 77.

- ^ T. Stephen Whitman, "Industrial Slavery at the Margin: the Maryland Chemical Works," Journal of Southern History 1993 59(1): 31-62,

- ^ Stephen Whitman, "Manumission and the Transformation of Urban Slavery," Social Science History 1995 19(3): 333-370

- ^ a b Collier-Thomas, Bettye (1974). The Baltimore Black Community, 1865-1910. Washington, DC: George Washington University.

- ^ Frank Towers, "Mobtown" (2012) p 470

- ^ ISBN 0-8139-2297-6.

- ^ Browne, Baltimore in the Nation, 1789-1861 (1980); Sheads and Toomey, Baltimore during the Civil War (1997).

- ^ Richard Paul Fuke, "Blacks, Whites, and Guns: Interracial Violence in Post-emancipation Maryland," Maryland Historical Magazine 1997 92(3): 326-347

- ^ Robert S. Wolff, "The Problem of Race in the Age of Freedom: Emancipation and the Transformation of Republican Schooling in Baltimore, 1860-1867," Civil War History 2006 52(3): 229-254

- ^ Eleanor S. Bruchey, "The Development of Baltimore Business, 1880-1914," Maryland Historical Magazine 1969 64(1): 18-42

- ^ Martha J. Vill, "Building Enterprise in Late Nineteenth-Century Baltimore," Journal of Historical Geograph 1986 12(2): 162-181,

- ^ YWCA Greater Baltimore: Our History, YWCA Greater Baltimore, retrieved 12 Apr 2016

- ^ a b Battaglia, Lynn A. (2011). ""Where is Justice?" An Exploration of Beginnings". University of Baltimore Law Forum. 42 (1): Article 2: pp. 1–37.

- ^ "Maryland Woman Suffrage Association". The History Engine. The University of Richmond. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ Elizabeth King Ellicott (1858-1914) MSA SC 3520-13588, Maryland State Archives, 5 Aug 2014, retrieved 11 Apr 2016

- ^ Commission on the Commemoration of the 100th anniversary of the passage of the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution, Maryland State Archives, 2 Dec 2015, retrieved 11 Apr 2016

- ^ The History of Johns Hopkins Medicine, Johns Hopkins Medicine, retrieved 11 Apr 2016

- ^ Morgan, Julia B. and Johns Hopkins: Knowledge for the World (2000), Women at the Johns Hopkins University: A History, Johns Hopkins University Press, retrieved 11 Apr 2016

- ISBN 9780521545709.

- ISBN 9780801819704.

- ^ Geoffrey L. Buckley, et al. "The Patapsco Forest Reserve: Establishing a 'City Park' for Baltimore, 1907-1941," Historical Geography 2006 34: 87-108

- ^ Peter T. Dalleo, and J. Vincent Watchorn, III, "Baltimore, the 'Babe,' and the Bethlehem Steel League, 1918," Maryland Historical Magazine 1998 93(1): 88-106,

- ^ Power, Garrett (May 1, 1983). "Apartheid Baltimore Style: The Residential Segregation Ordinances of 1910-1913". Faculty Scholarship. 184. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ^ Power, Garrett (May 1, 1983). "Apartheid Baltimore Style: The Residential Segregation Ordinances of 1910-1913". Faculty Scholarship. 184. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ^ Bock, James. "'Apartheid, Baltimore Style' City Housing Suit and History of Bias". The Baltimore Sun.

- ^ Jo Ann E. Argersinger, Toward a New Deal in Baltimore: People and Government in the Great Depression (1988)

- ^ Pelosi married and moved to San Francisco in the late 1960s.

- ^ Joshua B. Freeman, and Steve Rosswurm, "The Education of an Anti-Communist: Father John F. Cronin and the Baltimore Labor Movement," Labor History 1992 33(2): 217-247

- ^ Jill Jonnes, "Everybody Must Get Stoned: The Origins Of Modern Drug Culture In Baltimore," Maryland Historical Magazine 1996 91(2): 132-155

- ^ Appleton, Andrea (22 February 2012). "Helena Hicks: A participant in the Read's Drug Store sit-in talks about changing history on the spur of the moment". CityPaper. Archived from the original on 29 February 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ Ron Cassie, "And Service for All: Sixty years ago, Morgan State College students staged the first successful lunch-counter sit-ins", Baltimore Magazine, 19 January 2015.

- ^ David Milobsky, "Power from the Pulpit: Baltimore's African-American Clergy, 1950-1970," Maryland Historical Magazine 1994 89(3): 274-289,

- ^ Peter B. Levy, "The Dream Deferred: The Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and the Holy Week Uprisings of 1968," Maryland Historical Magazine (2013) 108#1 pp 57-78.

- ^ Timothy Wheeler, "City rioting evokes memories of 1968 unrest" The Baltimore Sun 28 April, 2015

- ^ Elizabeth Nix and Jessica Elfenbein, eds., Baltimore '68: Riots and Rebirth in an American City (2011), p. xiii excerpt

- ^ Kenneth Durr, "When Southern Politics Came North: the Roots of White Working-class Conservatism in Baltimore, 1940-1964," Labor History (1996) 37#3 pp: 309-331; Durr, Behind the Backlash: White Working-Class Politics in Baltimore, 1940-1980 (2003)

- ^ Mary Rizzo, 'Come and Be Shocked: Baltimore Beyond John Waters and The Wire.' (2020) https://www.press.jhu.edu/books/title/11744/come-and-be-shocked

- ^ Rousuck, J. Wynn; Gunts, Edward (January 25, 2005). "Hippodrome's first hurrahs". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ^ "UAE royal family honoured at opening of new Johns Hopkins Hospital". Middle East Health. May 2012. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ Gantz, Sarah (April 13, 2012). "Photos: Johns Hopkins dedicates $1.1 billion patient towers". Baltimore Business Journal. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ "Star-Spangled Sailabration". Sail Baltimore. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ "Baltimore's Star-Spangled Sailabration". The Washington Post. June 14, 2012. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ Kirk, Amy (September 15, 2014). "Military Members Wrap-up Baltimore Star Spangled Spectacular". United States Navy. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ "Star-Spangled Spectacular Shines the Limelight on Baltimore". Observation Baltimore. September 10, 2014. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- ^ Sheryl Gay Stolberg, "Crowds Scatter as Baltimore Curfew Takes Hold," New York Times, April 28, 2015

- ^ "Sagamore: A major opportunity that requires scrutiny equal in scale". Baltimore Sun. March 24, 2016. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ Martin, Olivia (September 22, 2016). "Baltimore city council approves $660 million for "Build Port Covington"". Archpaper.com. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ Plank, Kevin (September 7, 2016). "KP-BaltimoreSun-Ad-F.pdf" (PDF). An Open Letter from Kevin Plank. Build Port Covington. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ^ Jayne Miller (September 28, 2016). "Mayor signs Port Covington public financing legislation". Wbaltv.com. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ https://www.news.com.au/world/north-america/mass-casualty-incident-as-bridge-collapses-in-baltimore-us/news-story/adf08d9b0fd90f05b53e82350441629f

- ^ Spalding (1989)

- ^ Dee E. Andrews, The Methodists and Revolutionary America, 1760-1800: The Shaping of an Evangelical Culture (2000)

- ^ ISBN 9780271044125.

- ^ Rosalind Robinson Levering, Baltimore Baptists, 1773-1973: A History of the Baptist Work in Baltimore During 200 Years (1973) pp 97-168.

- Jewish Encyclopedia, ed. Isidore Singer, 1901–1906.

- ^ "Masjid Ul-Haqq". Baltimore Heritage. December 11, 2017. Retrieved March 10, 2020.

- ^ Rola Ghannam (January 8, 2018). "As Masjid Founders Pass Away, So Does Community History". Community News. The Muslim Link. Archived from the original on May 23, 2019.

- ^ Somerville, Frank P. L. (November 30, 1979). "Call to ring bells to support hostages gets discordant echoes from clergy". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved March 16, 2020.

- ^ Somerville, Frank P. L. (April 24, 1983). "Pratt's Islamic programs touch a nerve in Muslim community". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ Somerville, Frank P. L. (June 21, 1985). "Local Muslims celebrate end of month-long Ramadan fast". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved January 18, 2020.

- ^ Elaine, Tassy (February 27, 1995). "Children fast for Ramadan". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

Further reading

- Argersinger, Jo Ann E. Toward a New Deal in Baltimore: People and Government in the Great Depression (1988) online edition

- Argersinger, Jo Ann E. Making the Amalgamated: Gender, Ethnicity, and Class in the Baltimore Clothing Industry, 1899-1939 (1999) 229 pp.

- Arnold, Joseph L. "Baltimore: Southern Economy and a Northern Culture," in Richard M. Bernard, ed., Snowbelt Cities: Metropolitan Politics in the Northeast and Midwest since World War II (1990)

- Bilhartz, Terry D. Urban Religion and the Second Great Awakening: Church and Society in Early National Baltimore (1986)

- Browne, Gary Lawson. Baltimore in the Nation, 1789-1861 (1980). 349 pp.

- Brugger, Robert J. Maryland, A Middle Temperament: 1634-1980 (1988).

- Cowan, Aaron. A Nice Place to Visit: Tourism and Urban Revitalization in the Postwar Rustbelt (2016) compares Cincinnati, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, and Baltimore in the wake of deindustrialization.

- Durr, Kenneth D. Behind the Backlash: White Working Class Politics in Baltimore, 1940-1980 (2003) online edition

- Elfenbein, Jessica I.The Making of a Modern City: Philanthropy, Civic Culture, and the Baltimore YMCA (2001) 192 pp.

- Fee, Elizabeth, et al. eds. The Baltimore Book: New Views of Local History (1991). 256 pp. guide to the history and culture of working-class neighborhoods

- Hayward, Mary Ellen and Shivers, Frank R., Jr., eds. The Architecture of Baltimore: An Illustrated History (2004). 408 pp.

- Holli, Melvin G., and Jones, Peter d'A., eds. Biographical Dictionary of American Mayors, 1820-1980 (Greenwood Press, 1981) short scholarly biographies each of the city's mayors to 1980. online; see index at pp. 406–411 for list.

- Olson, Sherry H. Baltimore: The Building of an American City (1980). 432 pp. a fact (and picture) filled history

- Phillips, Christopher. Freedom's Port: The African American Community of Baltimore, 1790-1860 (1997)

- Rockman, Seth. Scraping By: Wage Labor, Slavery, and Survival in Early Baltimore (2009), 368 pp. social history online review

- Ryan, Mary P. Taking the Land to Make the City: A Bicoastal History of North America (University of Texas Press, 2019) 448pp.

- Sartain, Lee. Borders of Equality: The NAACP and the Baltimore Civil Rights Struggle, 1914-1970 (University Press of Mississippi, 2013) 235pp.

- Scharf, John Thomas. History of Baltimore City and County, from the earliest period to the present (1881) 935 pages online edition

- Schley, David. Steam City: Railroads, Urban Space, and Corporate Capitalism in Nineteenth-Century Baltimore (University of Chicago Press, 2020) 352pp.

- Shea, John Gilmary. Life and times of the Most Rev. John Carroll, bishop and first archbishop of Baltimore: Embracing the history of the Catholic Church in the United States. 1763-1815 (1888) 695pp online edition

- Sheads, Scott Sumpter and Daniel Carroll Toomey. Baltimore during the Civil War. (1997). 224 pp. Popular history

- Spalding, Thomas W. The Premier See: A History of the Archdiocese of Baltimore, 1789-1989 (1989)

- Steffen, Charles. The Mechanics of Baltimore: Workers and Politics in the Age of Revolution, 1763-1812 (1984)

- Towers, Frank. "Mobtown's Impact on the Study of Urban Politics in the Early Republic." Maryland Historical Magazine, 107 (Winter 2012) pp: 469-75

- Towers, Frank. "Job Busting at Baltimore Shipyards: Racial Violence in the Civil War-Era South." Journal of Southern History (2000): 221–256. in JSTOR

- Tuska, Benjamin. "Know-Nothingism in Baltimore 1854-1860." Catholic Historical Review 11.2 (1925): 217-251. online

External links

- Baltimore City Archives

- Baltimore City Historical Society

- Explore Baltimore Heritage

- Historical Society of Baltimore County

- Baltimore City, Maryland: Historical Chronology – Maryland State Archives

- Historical stories of Baltimore from the 1960s, 1950s, 1940s, 1930s, 1920s, 1910s - Ghosts of Baltimore blog