History of Maryland

The recorded history of Maryland dates back to the beginning of European exploration, starting with the

In 1781, during the

After the Revolutionary War, numerous Maryland planters freed their slaves as the economy changed.

Precolonial history

| History of Maryland |

|---|

|

|

It appears that the first humans in the area that would become Maryland arrived around the

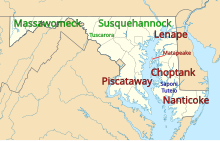

By 1000 AD, there were about 8,000 Native Americans, all

The following

When Europeans began to settle in Maryland in the early 17th century, the main tribes included the Nanticoke on the Eastern Shore, and the Iroquoian speaking Susquehannock. Early exposure to new European diseases brought widespread fatalities to the Native Americans, as they had no immunity to them. Communities were disrupted by such losses. Furthermore, The Susquehannock, already incorrectly considered savages and cannibals by the first Spanish explorers, made massive moves to control local trade with the first Swedish, Dutch and English settlers of the Chesapeake Bay region. As the century wore on, the Susquehannock would be caught up in the Beaver Wars, a war with the neighboring Lenape, a war with the Dutch, a war with the English, and a series of wars with the colonial government of Maryland. Due to colonial land claims, the exact territory of the Susquehannock was originally limited to the territory immediately surrounding the Susquehanna River, however archaeology has discovered settlements of theirs dating to the 14th and 15th centuries around the Maryland-West Virginia border, and beyond. It could generally be assumed that most of Maryland's southern border is based on the borders of their own land. All of these wars, coupled with disease, destroyed the tribe and the last of their people were offered refuge from the Iroquois Confederacy to the north shortly thereafter.[9]

The closest living language to them are the languages of the Mohawk and Tuscarora Iroquois, who once lived immediately north and south of them. The English and Dutch came to call them the Minqua, from Lenape, which breaks into min-kwe and translates to "as a woman." As to when they arrived, some early records detailing their oral history seem to point to the fact that they descended from an Iroquoian group who conquered Ohio centuries before, but were pushed back east again by Siouan and Algonquin enemies. They also conquered and absorbed other unknown groups in the process, which probably explains how languages like Tuscarora came to be so completely divergent from other Iroquoian languages. It also appears possible that the word "Iroquois" actually derived from their language.[10][11]

The Nanticoke seem to have been largely confined to Indian Towns,[12] but were later relocated to New York in 1778. Afterwards, they dissolved, with groups joining the Iroquois and Lenape.[13][14]

Also, as Susquehannocks began to abandon much of their westernmost territory due to their own hardships, a group of Powhatan split off, becoming known as the Shawnee and migrated into the western regions of Maryland and Pennsylvania briefly before moving on.[15] At the time, they were relatively small, but they eventually made the Ohio River, migrating all the way into Ohio and merged with other nations there to become the powerful, military force that they were known to be during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Early European exploration

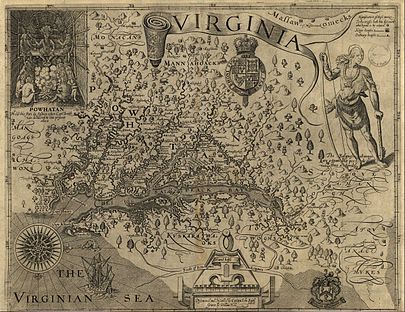

In 1498 the first European explorers sailed along the Eastern Shore, off present-day Worcester County.[16] In 1524 Giovanni da Verrazzano, sailing under the French flag, passed the mouth of Chesapeake Bay. In 1608 John Smith entered the bay[16] and explored it extensively. His maps have been preserved to today. Although technically crude, they are surprisingly accurate given the technology of those times (the maps are ornate but crude by modern technical standards).

The region was depicted in an earlier map by Estêvão Gomes and Diego Gutiérrez, made in 1562, in the context of the Spanish Ajacán Mission of the sixteenth century.[17]

Colonial Maryland

Establishment

Officially the colony is said to be named in honor of

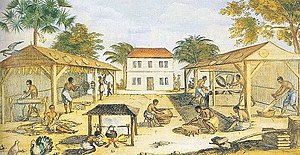

As did other colonies, Maryland used the

After purchasing land from the Yaocomico Indians and establishing the town of St. Mary's, Leonard, per his brother's instructions, attempted to govern the country under feudalistic precepts. Meeting resistance, in February 1635, he summoned a colonial assembly. In 1638, the Assembly forced him to govern according to the laws of England. The right to initiate legislation passed to the assembly.

In 1638 Calvert seized a trading post in

Maryland soon became one of the few predominantly Catholic regions among the English colonies in North America. Maryland was also one of the key destinations where the government sent tens of thousands of English convicts punished by sentences of transportation. Such punishment persisted until the Revolutionary War.

The Maryland Toleration Act, issued in 1649, was one of the first laws that explicitly defined tolerance of varieties of Christianity.

Protestant revolts

St. Mary's City was the largest settlement in Maryland and the seat of colonial government until 1695. Because

In 1650 the Puritans revolted against the proprietary government. They set up a new government prohibiting both Catholicism and Anglicanism. In March 1655, theIn 1689, following the accession of a Protestant monarchy in England, rebels against the Catholic regime in Maryland overthrew the government and took power. Lord Baltimore was stripped of his right to govern the province, though not of his territorial rights. Maryland was designated as a royal province, administered by the crown via appointed governors until 1715. At that time, Benedict Calvert, 4th Baron Baltimore, having converted to Anglicanism, was restored to proprietorship.[27]

The Protestant revolutionary government persecuted Maryland Catholics during its reign. Mobs burned down all the original Catholic churches of southern Maryland. The Anglican Church was made the established church of the colony. In 1695 the royal Governor, Francis Nicholson, moved the seat of government to Ann Arundell Town in Anne Arundel County and renamed it Annapolis in honor of the Princess Anne, who later became Queen Anne of Great Britain.[28] Annapolis remains the capital of Maryland. St. Mary's City is now an archaeological site, with a small tourist center.

Just as the city plan for St. Mary's City reflected the ideals of the founders, the city plan of Annapolis reflected those in power at the turn of the 18th century. The plan of Annapolis extends from two circles at the center of the city – one including the State House and the other the established Anglican St. Anne's Church (now Episcopal). The plan reflected a stronger relationship between church and state, and a colonial government more closely aligned with Protestant churches. General British policy regarding immigration to all British America would be reflected broadly in the Plantation Act of 1740.

Mason–Dixon Line

Based on an incorrect map, the original royal charter granted to Maryland the Potomac River and territory northward to the fortieth parallel. This was found to be a problem, as the northern boundary would have put Philadelphia, the major city in Pennsylvania, within Maryland. The Calvert family, which controlled Maryland, and the Penn family, which controlled Pennsylvania, decided in 1750 to engage two surveyors, Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, to establish a boundary between the colonies.

They surveyed what became known as the

Horse racing and gentry values

In Chesapeake society (that is, colonial Virginia and Maryland) sports occupied a great deal of attention at every social level. Horse racing was sponsored by the wealthy gentry plantation owners, and attracted ordinary farmers as spectators and gamblers. Selected slaves often became skilled horse trainers. Horse racing was especially important for knitting the gentry together. The race was a major public event designed to demonstrate to the world the superior social status of the gentry through expensive breeding and training of horses, boasting and gambling, and especially winning the races themselves.[30] Historian Timothy Breen explains that horseracing and high-stakes gambling were essential to maintaining the status of the gentry. When they publicly bet a large fraction of their wealth on their favorite horse, they expressed competitiveness, individualism, and materialism as the core elements of gentry values.[31]

The Revolutionary period

Maryland did not at first favor independence from Great Britain and gave instructions to that effect to its delegates to the Second Continental Congress. During this initial phase of the Revolutionary period, Maryland was governed by a series of conventions of the Assembly of Freemen. The first convention of the Assembly lasted four days, from June 22 to 25, 1774. All sixteen counties then existing were represented by a total of 92 members; Matthew Tilghman was elected chairman.[citation needed]

The eighth session decided that the continuation of an ad hoc government by the convention was not a good mechanism for all the concerns of the province. A more permanent and structured government was needed. So, on July 3, 1776, they resolved that a new convention be elected that would be responsible for drawing up their first

On March 1, 1781, the

No significant

The Second Continental Congress met briefly in Baltimore from December 20, 1776, through March 4, 1777 at the old hotel, later renamed Congress Hall, at the southwest corner of West Market Street (now Baltimore Street) and Sharp Street/Liberty Street. Marylander John Hanson, served as President of the Continental Congress from 1781 to 1782. Hanson was the first person to serve a full term with the title of "President of the United States in Congress Assembled" under the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union.[citation needed]

Major General William Smallwood, having served under General George Washington during the Revolutionary War, then Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, became the fourth American Governor of Maryland. In 1787, Governor William Smallwood called together and convened the state convention in order to decide whether to ratify the proposed U.S. Constitution in 1788. The majority of the votes at the convention were in favor of ratification, and Maryland became the seventh state to ratify the Constitution.[citation needed]

Maryland, 1789–1849

Economic development

The American Revolution stimulated the domestic market for wheat and iron ore, and flour milling increased in Baltimore. Iron ore transport greatly boosted the local economy. By 1800 Baltimore had become one of the major cities of the new republic. The British naval blockade during the War of 1812 hurt Baltimore's shipping, but also freed merchants and traders from British debts, which along with the capture of British merchant vessels furthered the city's economic growth.

Transportation initiatives

The city had a deepwater port. In the early 19th century, many business leaders in Maryland were looking inland, toward the western frontier, for economic growth potential. The challenge was to devise a reliable means to transport goods and people. The National Road and private turnpikes were being completed throughout the state, but additional routes and capacity were needed. Following the success of the Erie Canal (constructed 1817–25) and similar canals in the northeastern states, leaders in Maryland were also developing plans for canals. After several failed canal projects in the Washington, D.C. area, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (C&O) began construction there in 1828. The Baltimore business community viewed this project as a competitive threat. The geography of the Baltimore area made building a similar canal to the west impractical, but the idea of constructing railroads was beginning to gather support in the 1820s.

In 1827 city leaders obtained a charter from the Maryland General Assembly to build a railroad to the Ohio River.[35]: 17 The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O) became the first chartered railroad in the United States, and opened its first section of track for regular operation in 1830, between Baltimore and Ellicott City.[36]: 80 It became the first company to operate a locomotive built in America, with the Tom Thumb.[37] The B&O built a branch line to Washington, D.C. in 1835.[36]: 184 The main line west reached Cumberland in 1842, beating the C&O Canal there by eight years, and the railroad continued building westward.[35]: 54 In 1852 it became the first rail line to reach the Ohio River from the eastern seaboard.[35]: 18 Other railroads were built in and through Baltimore by mid-century, most significantly the Northern Central; the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore; and the Baltimore and Potomac. (All of these came under the control of the Pennsylvania Railroad.)

Industrial Revolution

Baltimore's seaport and good railroad connections fostered substantial growth during the Industrial Revolution of the 19th century. Many manufacturing businesses were established in Baltimore and the surrounding area after the Civil War.

Cumberland was Maryland's second largest city in the 19th century, with ample nearby supplies of coal, iron ore and timber. These resources, along with railroads, the National Road and the C&O Canal, fostered its growth. The city was a major manufacturing center, with industries in glass, breweries, fabrics and tinplate.

The Pennsylvania Steel Company founded a steel mill at Sparrow's Point in Baltimore in 1887. The mill was purchased by Bethlehem Steel in 1916, and it became the world's largest steel mill by the mid-20th century, employing tens of thousands of workers.[38]

Educational institutions

In 1807, the College of Medicine of Maryland (later the

In 1840, by order of the Maryland state legislature, the non-religious St. Mary's Female Seminary was founded in St. Mary's City. This would later become St. Mary's College of Maryland, the state's public honors college. The United States Naval Academy was founded in Annapolis in 1845, and the Maryland Agricultural College was chartered in 1856, growing eventually into the University of Maryland.

Immigration and religion

Since the abolition of anti-Catholic laws[citation needed] in the early 1830s, the Catholic population rebounded considerably. The Maryland Catholic population began its resurgence with large waves of Irish Catholic immigration spurred by the

War of 1812

After the Revolution, the

During the War of 1812 the British raided cities along Chesapeake Bay up to Havre de Grace. Two notable battles occurred in the state. The first was the Battle of Bladensburg on August 24, 1814, just outside the national capital, Washington, D.C. The British army routed the American militiamen, who fled in confusion, and went on to capture Washington, D.C. They burned and looted major public buildings, forcing President James Madison to flee to Brookeville, Maryland.[citation needed]

The British next marched to

After advancing to the edge of American defenses, the British halted their advance and withdrew. With the failure of the land advance, the sea battle became irrelevant and the British retreated.

At

American Civil War

Maryland's mixed sympathies

Maryland was a

After

Beginning of the war

The first bloodshed of the war

Maryland remained part of the Union during the Civil War. President Abraham Lincoln's strong hand suppressing violence and dissent in Maryland and the belated assistance of Governor Hicks played important roles. Hicks worked with federal officials to stop further violence.

Lincoln promised to avoid having Northern defenders march through Baltimore while en route to protect the acutely endangered federal capital. The majority of forces took a slow route by boat. Massachusetts militia general

He landed his troops of Massachusetts, New York and Rhode Island militia over the protests of Governor

Marylanders sympathetic to the South easily crossed the Potomac River to join and fight for the Confederacy. Exiles organized a "Maryland Line" in the Army of Northern Virginia which consisted of one infantry regiment, one infantry battalion, two cavalry battalions and four battalions of artillery. According to the best extant records, up to 25,000 Marylanders went south to fight for the Confederacy.[citation needed] About 60,000 Marylanders served in all branches of the Union military. Many of the Union troops were said to enlist on the promise of home garrison duty.[citation needed]

Maryland's naval contribution, the relatively new sloop-of-war

Occupation of Baltimore

A Union artillery garrison was placed on

Because Maryland remained in the Union, it fell outside the scope of the

The war on Maryland soil

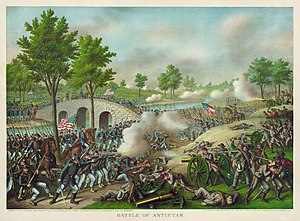

The largest and most significant battle fought in the state was the

While Major General George B. McClellan's 87,000-man Army of the Potomac was moving to intercept Lee, a Union soldier discovered a mislaid copy of the detailed battle plans of Lee's army. The order indicated that Lee had divided his army and dispersed portions geographically (to Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, and Hagerstown, Maryland), thus making each subject to isolation and defeat in detail if McClellan could move quickly enough. McClellan waited about 18 hours before deciding to take advantage of this intelligence and position his forces based on it, thus endangering a golden opportunity to defeat Lee decisively.

The armies met near the town of Sharpsburg by Antietam Creek. Although McClellan arrived in the area on September 16, his trademark caution delayed his attack on Lee, which gave the Confederates more time to prepare defensive positions and allowed Longstreet's corps to arrive from Hagerstown and Jackson's corps, minus A. P. Hill's division, to arrive from Harpers Ferry. McClellan's two-to-one advantage in the battle was almost completely nullified by a lack of coordination and concentration of Union forces, which allowed Lee to shift his defensive forces to parry each thrust.

Although a tactical draw, the Battle of Antietam was considered a strategic Union victory and a turning point of the war. It forced the end of Lee's invasion of the North. It also was enough of a victory to enable President Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, which took effect on January 1, 1863. He had been advised by his Cabinet to make the announcement after a Union victory, to avoid any perception that it was issued out of desperation. The Union's winning the Battle of Antietam also may have dissuaded the governments of France and Great Britain from recognizing the Confederacy. Some observers believed they might have done so in the aftermath of another Union defeat.

Maryland, 1865–1920

Post-Civil War political developments

Since Maryland had remained in the Union during the Civil War, the state was not covered by the

In the late 1860s, the white males of the

In 1896, a biracial Republican coalition gained election of

In 1910, the legislature proposed the Digges Amendment to the state constitution. It would have used property requirements to effectively disfranchise many African American men as well as many poor white men (including new immigrants), a technique used by other southern states from 1890 to 1910, beginning with Mississippi's new constitution. The Maryland General Assembly passed the bill, which Governor Austin Lane Crothers supported. Before the measure went to popular vote, a bill was proposed that would have effectively passed the requirements of the Digges Amendment into law. Due to widespread public opposition, that measure failed, and the amendment was also rejected by the voters of Maryland.

Nationally Maryland citizens achieved the most notable rejection of a black-disfranchising amendment.[44] Similar measures had earlier been proposed in Maryland, but also failed to pass (the Poe Amendment in 1905 and the Straus Amendment in 1909). The power of black men at the ballot box and economically helped them resist these bills and disfranchising effort.[44]

Businessmen Johns Hopkins, Enoch Pratt, George Peabody, and Henry Walters were philanthropists of 19th century Baltimore; they founded notable educational, health care, and cultural institutions in that city. Bearing their names, these include a university, free city library, music and art school, and art museum.

Progressive era reforms

In the early 20th century, a political reform movement arose, centered in the rising new middle class. One of their main goals included having government jobs granted on the basis of merit rather than patronage. Other changes aimed to reduce the power of political bosses and machines, which they succeeded in doing.

In a series of laws passed between 1892 and 1908, reformers worked for standard state-issued ballots (rather than those distributed and pre-marked by the parties); obtained closed voting booths to prevent party workers from "assisting" voters; initiated

Other laws regulated working conditions. For instance, in a series of laws passed in 1902, the state regulated conditions in

The debate over prohibition of alcohol, another progressive reform, led to Maryland's gaining its second nickname. A mocking newspaper editorial dubbed Maryland "the Free State" for its allowing alcohol.[19][34]

Great Baltimore Fire

The Great Baltimore Fire of 1904 was a momentous event for Maryland's largest city and the state as a whole. The fire raged in Baltimore from 10:48 a.m. Sunday, February 7, to 5:00 p.m. Monday, February 8, 1904. More than 1,231 firefighters worked to bring the blaze under control.

One reason for the fire's duration was the lack of national standards in fire-fighting equipment. Although fire engines from nearby cities (such as Philadelphia and Washington, as well as units from New York, Wilmington, and Atlantic City) responded, many were useless because their hose couples failed to fit Baltimore hydrants. As a result, the fire burned over 30 hours, destroying 1,526 buildings and spanning 70 city blocks.

In the aftermath, 35,000 people were left unemployed. After the fire, the city was rebuilt using more fireproof materials, such as granite pavers.

The World War I era

Entry into World War I brought changes to Maryland.

Maryland was the site of new military bases, such as Camp Meade (now

To coordinate wartime activities, like the expansion of federal facilities, the General Assembly set up a Council of Defense. The 126 seats on the council were filled by appointment.[clarification needed] The council, which had a virtually unlimited budget, was charged with defending the state, supervising the draft, maintaining wage and price controls, providing housing for war-related industries, and promoting support for the war. Citizens were encouraged to grow their own victory gardens and to obey ration laws. They were also forced to work, once the legislature adopted a compulsory labor law with the support of the Council of Defense.

Culture

H. L. Mencken (1880–1956) was the state's iconoclastic writer and intellectual trendsetter. In 1922 the "Sage of Baltimore" praised the state for its "singular and various beauty from the stately estuaries of the Chesapeake to the peaks of the Blue Ridge." He happily reported that Providence had spared Maryland the harsh weather, the decay, the intractable social problems of other states. Statistically, Maryland held tightly to the middle ground– in population, value of manufacturers, percentage of native whites, the proportion of Catholics, the first and last annual frost. Everywhere he looked he found Maryland in the middle. In national politics it worked sometimes with the northern Republicans, other times with southern Democrats. This average quality perhaps represented a national ideal toward which other states were striving. Nevertheless, Mencken sensed something was wrong. "Men are ironed out. Ideas are suspect. No one appears to be happy. Life is dull."[45]

Maryland, early to mid-20th century

The Ritchie administration

In 1918, Maryland elected

The Great Depression and World War II

Maryland's urban and rural communities had different experiences during the Depression. In 1932 the "Bonus Army" marched through the state on its way to Washington, D.C. In addition to the nationwide New Deal reforms of President Roosevelt, which put people to work building roads and park facilities, Maryland also took steps to weather the hard times. For instance, in 1937 the state instituted its first ever income tax to generate revenue for schools and welfare.[citation needed]

The state had some advances in

A hurricane in 1933 created an inlet in

Mid-20th century

In 1952, the eastern and western halves of Maryland were linked for the first time by the long

Maryland, late 20th century to present

In 1980, the opening of

In addition to general suburban growth, specially planned new communities sprung up, most notably

See also

- Outline of Maryland#History of Maryland

- Government of Maryland

- Colonial South and the Chesapeake

- History of the Southern United States

- History of Washington, D.C.

- List of people from Maryland

- Timeline of Baltimore

- African Americans in Maryland

- Maryland in the American Civil War

- History of slavery in Maryland

References

- ^ Greenwell, Megan. "Religious Freedom Byway Would Recognize Maryland's Historic Role", Washington Post, August 21, 2008.

- ^ Calvert, Cecilius. "Instructions to the Colonists by Lord Baltimore, (1633)", Narratives of Early Maryland, 1633–1684 (Clayton Coleman Hall, ed.), (NY: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1910), 11–23.

- ^ "Reconstructing the Brick Chapel of 1667" (PDF). p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 13, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- ^ a b Kolchin, Peter. American Slavery: 1619–1877, New York: Hill and Wang, 1993, pp. 81–82

- ^ See John Smith's map of Virginia on Wikimedia Commons.

- ^ John Steckley, "The Early Map "Novvelle France": A Linguistic Analysis", Ontario Archaeology 51, 1990.

- ^ Reynolds, Patrick M. (April 11, 2010). "Flashback column:The Tribes of Maryland". The Washington Post. Washington, DC. pp. SC9.

- ^ John Heckewelder (Loskiel): Conoys, Ganawese, etc. explains Charles A. Hanna (Vol II, 1911:96, Ganeiens-gaa, Margry, i., 529; ii., 142–43,) using La Salle's letter of August 22, 1681 Fort Saint Louis (Illinois) mentioning "Ohio tribes" for extrapolation.

- ^ "Susquehannocks – The vanquished tribe | Our Cecil". cecildaily.com. May 17, 2014. Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- ^ Nichols, John & Nyholm, Earl "The Concise Dictionary of Minnesota Ojibwe." 1994

- ^ "On the Susquehannocks: Natives having used Baltimore County as hunting grounds | The Historical Society of Baltimore County". Hsobc.org. Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- ^ "Restore Handsell – History of Handsell in the Chicone Indiantown, Dorchester County, Maryland". Restorehandsell.org. April 30, 2017. Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- ^ Pritzker 441

- ^ Durham, Raymond (February 29, 2012). "References to Native Americans of Delmarva on the internet" (PDF). Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- ^ Carrie Hunter Willis and Etta Belle Walker, Legends of the Skyline Drive and the Great Valley of Virginia, 1937, pp. 15–16; this account also appears in T.K. Cartmell's 1909 Shenandoah Valley Pioneers and Their Descendants p. 41.

- ^ a b Maryland State Archives, Annapolis, MD (2013). "Maryland Historical Chronology: 10,000 B.C. – 1599." Maryland Manual On-Line.

- ^ "The Spanish in the Chesapeake Bay". Charles A. Grymes. Archived from the original on October 11, 2012. Retrieved March 17, 2013.

- ^ "The Charter of Maryland : 1632", The Avalon Project, Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale School of Law

- ^ a b c d "Maryland at a Glance: Name". Maryland State Archives. Retrieved February 7, 2007.

- ^ Carl, Katy. "Catholics Give Thanks to God in Maryland", National Catholic Register, November 21, 2012

- Houghton Mifflin. pp. 42–43.

- ISBN 978-1-57233-888-3.

- ^ King 2012, p. 85.

- ^ "MD History". Maryland Historical Society. Retrieved February 2, 2018.

- ^ Owen M. Taylor, History of Annapolis (1872) p 5 online

- ^ Daniel R. Randall, A Puritan Colony in Maryland; Johns Hopkins University Studies in History and Political Science, ed. Herbert B. Adams, Fourth Series, issue VI; Baltimore: N. Murray for Johns Hopkins University, June 1886.

- ^ Mereness (1901), pp. 37–43.

- ISBN 978-1-4214-2622-8.

- ^ Anderson, David (May 20, 2016). "Travel back in time 250 years with Mason-Dixon Line marker in northern Harford". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- ^ Nancy L. Struna, "The Formalizing of Sport and the Formation of an Elite: The Chesapeake Gentry, 1650–1720s." Journal of Sport History 13#3 (1986). online Archived August 22, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Timothy H. Breen, "Horses and gentlemen: The cultural significance of gambling among the gentry of Virginia." William and Mary Quarterly (1977) 34#2 pp: 239-257. online

- ^ Sioussat, St. George L. (October 1936). "THE CHEVALIER DE LA LUZERNE AND THE RATIFICATION OF THE ARTICLES OF CONFEDERATION BY MARYLAND, 1780–1781 With Accompanying Documents". The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. 60 (4): 391–418. Retrieved April 19, 2018.

- ^ "An ACT to empower the delegates". Laws of Maryland, 1781. February 2, 1781. Archived from the original on July 23, 2011.

- ^ a b Montgomery, Lori (March 14, 2000). "Two-Bit Identity Crisis; Imprint Befuddles the Free—Make That 'Old Line'—State". The Washington Post. gwpapers.virginia.edu. Archived from the original on June 3, 2010. Retrieved October 7, 2009.

- ^ ISBN 0-911198-81-4.

- ^ ISBN 0-8047-2235-8.

- OCLC 3616164.

- ISBN 978-0-252-07233-8.

- ^ "The Earliest North American Medical Schools: Chronological List of Founding Dates". Essay::Health Sciences Library. Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, N.Y. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ^ a b "Irish Immigrants in Baltimore: Introduction", Teaching American History in Maryland, Maryland State Archives, http://teaching.msa.maryland.gov/000001/000000/000131/html/t131.html

- ^ a b "Italian Jesuits in Maryland : a clash of theological cultures (2007)", McKevitt, Gerald, Volume: v.39 no.1, pages 50, 51, 52; Publisher: St. Louis, MO : Seminar on Jesuit Spirituality, Call number: BX3701.S88x, Digitizing sponsor: Boston Library Consortium Member Libraries https://archive.org/details/italianjesuitsin391mcke

- ^ Cleveland, J. F. (1861). The Tribune Almanac and Political Register, Volume 1861. New York: Tribune Association. p. 49.

- ^ Nevins, Allan (1959). The War for the Union: The Improvised War, 1861–1862. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 87.

- ^ a b c d STEPHEN TUCK, "Democratization and the Disfranchisement of African Americans in the US South during the Late 19th Century" (pdf), Spring 2013, reading for "Challenges of Democratization", by Brandon Kendhammer, Ohio University

- ISBN 9780801854651.

- ^ Joseph B. Chepaitis, "Albert C. Ritchie in Power: 1920–1927". Maryland Historical Magazine (1973) 68(4): 383–404

- ^ Dorothy Brown, "The Election of 1934: the 'New Deal' in Maryland," Maryland Historical Magazine (1973) 68(4): 405–421

- ^ "William Preston Lane Jr. Memorial Bay Bridge – History". baybridge.com. Archived from the original on July 1, 2008. Retrieved February 5, 2008.

- ^ "Business in Maryland: Biosciences". Maryland Department of Business & Economic Development. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- ^ Goodman, Peter S. (August 1, 1999). "An Unsavory Byproduct: Runoff and Pollution". The Washington Post. p. A1.

- ^ Horton, Tom (January 1, 1999). "Hog farms' waste poses a threat". Baltimore Sun.

- ^ Fahrenthold, David A. (October 25, 2010). "Losing Battle Against the Bay". The Washington Post.

Further reading

- Timeline of Maryland: – via HathiTrust.

- Brugger, Robert J. Maryland, A Middle Temperament: 1634–1980 (1996) full scale history

- Chappelle, Suzanne. Jean H. Baker, Dean R. Esslinger, and Whitman H. Ridgeway. Maryland: A History of its People (1986)

Colonial to 1860

- Arson, Steven, "Yeoman Farmers in a Planters' Republic: Socioeconomic Conditions and Relations in Early National Prince George's County, Maryland," Journal of the Early Republic, 29 (Spring 2009), 63–99.

- Brackett; Jeffrey R. The Negro in Maryland: A Study of the Institution of Slavery (1969) online edition

- Browne, Gary Lawson. Baltimore in the Nation, 1789–1861 (1980)

- Carr, Lois Green, Philip D. Morgan, Jean Burrell Russo, eds. Colonial Chesapeake Society (1991)

- Craven, Avery. Soil Exhaustion as a Factor in the Agricultural History of Virginia and Maryland, 1606–1860 (1925; reprinted 2006)

- Curran, Robert Emmett, ed. Shaping American Catholicism: Maryland and New York, 1805–1915 (2012) excerpt and text search

- Curran, Robert Emmett. Papist Devils: Catholics in British America, 1574–1783 (2014)

- Fields, Barbara. Slavery and Freedom on the Middle Ground: Maryland During the Nineteenth Century (1987)

- Hoffman, Ronald. Princes of Ireland, Planters of Maryland: A Carroll Saga, 1500–1782 (2000) 429pp ISBN 0-8078-2556-5.

- Hoffman, Ronald. A Spirit of Dissension: Economics, Politics, and the Revolution in Maryland (1973)

- Kulikoff, Allan. Tobacco and Slaves: The Development of Southern Cultures in the Chesapeake, 1680–1800 (1988)

- Main, Gloria L. Tobacco Colony: Life in Early Maryland, 1650–1720 (1983)

- Mereness, Newton Dennison. Maryland as a Proprietary Province. New York: Macmillan, 1901.

- Middleton, Arthur Pierce. Tobacco Coast: A Maritime History of Chesapeake Bay in the Colonial Era (1984) online edition

- Risjord; Norman K. Chesapeake Politics, 1781–1800 (1978) online edition

- Steiner; Bernard C. Maryland under the Commonwealth: A Chronicle of the Years 1649–1658 1911

- Tate, Thad W. ed. The Chesapeake in the seventeenth century: Essays on Anglo-American society (1979), scholarly studies

Since 1860

- Anderson, Alan D. The Origin and Resolution of an Urban Crisis: Baltimore, 1890–1930 (1977)

- Argersinger, Jo Ann E. Toward a New Deal in Baltimore: People and Government in the Great Depression (1988)

- Durr, Kenneth D. Behind the Backlash: White Working-Class Politics in Baltimore, 1940–1980 University of North Carolina Press, 2003 online edition

- Ellis; John Tracy The Life of James Cardinal Gibbons: Archbishop of Baltimore, 1834–1921 2 vol 1952 online edition v.1; online ed. v.2

- Fein, Isaac M. The Making of an American Jewish Community: The History of Baltimore Jewry from 1773 to 1920 1971 online edition

- Wennersten, John R. Maryland's Eastern Shore: A Journey in Time and Place (1992)

Primary sources

- Clayton Colman Hall, ed. Narratives of Early Maryland, 1633–1684 (1910) 460 pp. online edition

- David Hein, editor. Religion and Politics in Maryland on the Eve of the Civil War: The Letters of W. Wilkins Davis. 1988; revised ed., Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock, 2009.

Online essays

- Maryland State Archives (September 16, 2004).Historical Chronology.

- Whitman H. Ridgway. Maryland Humanities Council (2001). "(Maryland) Politics and Law"

- Maryland State Archives. (October 29, 2004).Maryland Manual On-Line: A Guide to Maryland Government. Retrieved June 1, 2005.

- "Maryland". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 22, 2005.

- "Maryland". The Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved May 22, 2005.

- Dennis C. Curry (2001). "Native Maryland, 9000 B.C.–1600 A.D.".

- Whitman H. Ridgway. Maryland Humanities Council (2001). "(Maryland in) the Nineteenth Century".

- George H. Callcott. Maryland Humanities Council (2001). "(Maryland in) the Twentieth Century".

External links

- Maryland Historical Society

- Maryland Military Historical Society

- Maryland State Archives

- Maryland: State Resource Guide, from the Library of Congress

- Boston Public Library, Map Center. Maps of Maryland, various dates.

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.