History of robots

The history of robots has its origins in the

The first uses of modern robots were in

Early legends

Concepts of artificial servants and companions date at least as far back as the ancient legends of Cadmus, who is said to have sown dragon teeth that turned into soldiers and Pygmalion whose statue of Galatea came to life. Many ancient mythologies included artificial people, such as the talking mechanical handmaidens (Ancient Greek: Κουραι Χρυσεαι (Kourai Khryseai); "Golden Maidens"[1]) built by the Greek god Hephaestus (Vulcan to the Romans) out of gold.[2]

The Buddhist scholar

Early Chinese lore on the legendary carpenter

The Indian

Inspired by European

Automata

In the 4th century BC the mathematician

There is only one condition in which we can imagine managers not needing subordinates, and masters not needing slaves. This condition would be that each instrument could do its own work, at the word of command or by intelligent anticipation, like the statues of Daedalus or the tripods made by Hephaestus, of which Homer relates that "Of their own motion they entered the conclave of Gods on Olympus", as if a shuttle should weave of itself, and a plectrum should do its own harp playing.

When the Greeks controlled Egypt, a succession of engineers who could construct automata established themselves in Alexandria. Starting with the polymath Ctesibius (285-222 BC), Alexandrian engineers left behind texts detailing workable automata powered by hydraulics or steam. Ctesibius built human-like automata, often these were used in religious ceremonies and the worship of deities. One of the last great Alexandrian engineers, Hero of Alexandria (10-70 CE) constructed an automata puppet theater, where the figurines and the stage sets moved by mechanical means. He described the construction of such automata in his treatise on pneumatics.[14] Alexandrian engineers constructed automata as reverence for humans' apparent command over nature and as tools for priests, but also started a tradition where automata were constructed for anyone who was wealthy enough and primarily for the entertainment of the rich.[15]

The manufacturing tradition of automata continued in the Greek world well into the Middle Ages. On his visit to Constantinople in 949 ambassador Liutprand of Cremona described automata in the emperor Theophilos' palace, including

"lions, made either of bronze or wood covered with gold, which struck the ground with their tails and roared with open mouth and quivering tongue," "a tree of gilded bronze, its branches filled with birds, likewise made of bronze gilded over, and these emitted cries appropriate to their species" and "the emperor's throne" itself, which "was made in such a cunning manner that at one moment it was down on the ground, while at another it rose higher and was to be seen up in the air."[16]

Similar automata in the throne room (singing birds, roaring and moving lions) were described by Luitprand's contemporary, the Byzantine emperor

In China the Cosmic Engine, a 10-metre (33 ft) clock tower built by

Post-classical societies such as the

The

Among the first verifiable automation is a

The 17th-century thinker

In the 1770s the Swiss

In the 19th century the Japanese craftsman

Modern history

1900s

Starting in 1900,

In 1903, the Spanish engineer

1910s

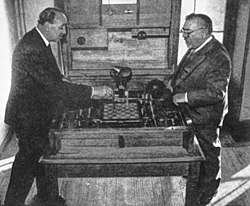

In 1912, Leonardo Torres Quevedo built the first truly autonomous machine capable of playing chess. As opposed to the human-operated The Turk and Ajeeb, El Ajedrecista (The Chessplayer) had a true integrated automation built to play chess without human guidance. It only played an endgame with three chess pieces, automatically moving a white king and a rook to checkmate the black king moved by a human opponent.[43][44] In 1951 El Ajedrecista defeats Savielly Tartakower at the Paris Cybernetic Conference, being the first Grandmaster to be defeated by a machine.[45] In his 1914 paper Essays on Automatics, Torres proposed a machine that makes "judgments" using sensors that capture information from the outside, parts that manipulate the outside world like arms, power sources such as batteries and air pressure, and most importantly, captured information and past information. It was defined as an organism that can control reactions in response to external information and adapt to changes in the environment to change its behavior.[46][47][48][49]

1920s

The term "robot" was first used in a play published by the Czech

Westinghouse Electric Corporation built Televox in 1926; it was a cardboard cutout connected to various devices which users could turn on and off.[53] In 1927, Fritz Lang's Metropolis was released; the Maschinenmensch ("machine-human"), a gynoid humanoid robot, also called "Parody", "Futura", "Robotrix", or the "Maria impersonator" (played by German actress Brigitte Helm), was the first robot ever to be depicted on film.[54]

The most famous Japanese robotic automaton was presented to the public in 1927. The

1930s

The earliest designs of

In 1939, the humanoid robot known as

In 1939

1940s

In 1941 and 1942, Isaac Asimov formulated the Three Laws of Robotics, and in the process coined the word "robotics".[citation needed] In 1945 Vannevar Bush published As We May Think, an essay that investigated the potential of electronic data processing. He predicted the rise of computers, digital word processors, voice recognition and machine translation. He was later credited by Ted Nelson, the inventor of hypertext.[18]

In 1943

The first electronic autonomous robots with complex behavior were created by

Walter stressed the importance of using purely

In 1949 Tony Sale built a simple 6-foot (1.8 m) humanoid robot he named George, created from scrap metal from a grounded Wellington bomber. After being stored away in its inventor's shed, the robot was restored in 2010 and shown in an episode of Wallace & Gromit's World of Invention. After the reactivation, Tony Sale donated George to the National Museum of Computing, where it remains on display to the public.

1950s

In 1951 Walter published the paper A Machine that learns, documenting how his more advanced mechanical robots acted as intelligent agent by demonstrating conditioned reflex learning.[18]

Unimate, the first digitally operated and programmable robot, was invented by George Devol in 1950 and "represents the foundation of the modern robotics industry."[65][66]

In Japan, robots became popular comic book characters. Robots became cultural icons and the Japanese government was spurred into funding research into robotics. Among the most iconic characters was the Astro Boy, who is taught human feelings such as love, courage and self-doubt. Culturally, robots in Japan became regarded as helpmates to their human counterparts.[67]

The introduction of

1960s

Devol sold the first Unimate to General Motors in 1960, and it was installed in 1961 in a plant in Ewing Township, New Jersey, to lift hot pieces of metal from a die casting machine and place them in cooling liquid.[70][71] "Without any fanfare, the world's first working robot joined the assembly line at the General Motors plant in Ewing Township in the spring of 1961... It was an automated die-casting mold that dropped red-hot door handles and other such car parts into pools of cooling liquid on a line that moved them along to workers for trimming and buffing." Devol's patent for the first digitally operated programmable robotic arm represents the foundation of the modern robotics industry.[72]

The Rancho Arm was developed as a robotic arm to help handicapped patients at the

In the late-1960s the

1970s

In the early 1970s precision munitions and smart weapons were developed. Weapons became robotic by implementing terminal guidance. At the end of the Vietnam War the first laser-guided bombs were deployed, which could find their target by following a laser beam that was pointed at the target. During the 1972 Operation Linebacker laser-guided bombs proved effective, but still depended heavily on human operators. Fire-and-forget weapons were also first deployed in the closing Vietnam War, once launched no further attention or action was required from the operator.[76]

The development of humanoid robots was advanced considerably by Japanese robotics scientists in the 1970s.[77] Waseda University initiated the WABOT project in 1967, and in 1972 completed the WABOT-1, the world's first full-scale humanoid intelligent robot.[78] Its limb control system allowed it to walk with the lower limbs, and to grip and transport objects with hands, using tactile sensors. Its vision system allowed it to measure distances and directions to objects using external receptors, artificial eyes and ears. And its conversation system allowed it to communicate with a person in Japanese, with an artificial mouth. This made it the first android.[79][80]

In 1974,

In 1974, David Silver designed The Silver Arm, which was capable of fine movements replicating human hands. Feedback was provided by

The Stanford Cart successfully crossed a room full of chairs in 1979. It relied primarily on

1980s

Takeo Kanade created the first "direct-drive arm" in 1981. The first of its kind, the arm's motors were contained within the robot itself, eliminating long transmissions.[89]

In 1984 Wabot-2 was revealed; capable of playing the organ, Wabot-2 had 10 fingers and two feet. Wabot-2 was able to read a score of music and accompany a person.[90]

In 1986,

1990s

In 1994 one of the most successful

The

Honda's

Expected to operate for only seven days, the Sojourner rover finally shuts down after 83 days of operation in 1997. This small robot (only 23 lbs or 10.5 kg) performed semi-autonomous operations on the surface of Mars as part of the Mars Pathfinder mission; equipped with an obstacle avoidance program, Sojourner was capable of planning and navigating routes to study the surface of the planet. Sojourner's ability to navigate with little data about its environment and nearby surroundings allowed it to react to unplanned events and objects.[97]

The

2000s

In April 2001, the

The popular Roomba, a robotic vacuum cleaner, was first released in 2002 by the company iRobot.[104]

In 2002, in her book Designing Sociable Robots, Cynthia Breazeal was one of the first to explore the idea of robots imitating humans, and published research on how, in the future, teaching humanoid robots to perform new tasks might be as simple as just showing them.[105] Throughout the early 2000s Breazeal was experimenting with expressive social exchange between humans and humanoid robots. Whilst completing her PhD at MIT, she worked on humanoid robots Kismet, Leonard, Aida, Autom and Huggable.[106] Doing this, Breazeal found that the issue was that robots too often only interacted with objects and not people and suggested that robots can be used to better relationships between humans.

In 2005, Cornell University revealed a robotic system of block-modules capable of attaching and detaching, described as the first robot capable of self-replication, because it was capable of assembling copies of itself if it was placed near more of the blocks which composed it.[107] Launched in 2003, on 3 and 24 January, the Mars rovers Spirit and Opportunity landed on the surface of Mars. Both robots drove many times the distance originally expected, and Opportunity was still operating as late as mid-2018, before communications were lost due to a major dust storm.[108]

2010s

The 2010s were defined by large-scale improvements in the availability, power and versatility of commonly available robotic components, as well as the mass proliferation of robots into everyday life, which caused both optimistic speculation and new societal concerns.

Development of humanoid robots continued to advance;

The cost and weight reductions of these components have resulted in a proliferation of new kinds of special-purpose robots. Quadcopters, a novelty at the beginning of the decade, became a ubiquitous platform for robotic systems, featuring autonomous navigation and stabilization and carrying increasingly powerful sensors, including stabilized high definition cameras, radar, and surveying equipment. By the end of the decade, the cost of a robotic quadcopter with 4K cameras and autonomous navigation had dropped to within range of hobbyist budgets,[114] and companies like Amazon were exploring the use of quadcopters to autonomously deliver freight, though deployment of this systems did not happen on a large scale in the decade.[115]

The decade also saw a boom in the capabilities of

The 2010s also saw the growth of new software paradigms, which allowed robots and their AI systems to take advantage of this increased computing power.

The growth of robots in the 2010s also coincided with the increasing power of the

The growth of robotic capabilities during the decade happened in tandem with the centralization of economic power into the hands of

Throughout the 2010s, humans continued to examine the nature of their relationships with robots, with trends indicating a general belief that robots were or would become conscious beings deserving of rights, and potential allies or rivals to humans. On 25 October 2017 at the Future Investment Summit in Riyadh, a robot called Sophia and referred to with female pronouns was granted Saudi Arabian citizenship, becoming the first robot ever to have a nationality.[124][125] This has attracted controversy, as it is not obvious whether this implies that Sophia can vote or marry, or whether a deliberate system shutdown can be considered murder; as well, it is controversial considering how few rights are given to Saudi human women.[126][127] Popular works of art in the 2010s, such as HBO's revival of Westworld, encouraged empathy for robots, and explored questions of humanity and consciousness.[128]

By the end of the decade, commercial and industrial robots were in widespread use, performing jobs more cheaply or with greater accuracy and reliability than humans, and were widely used in manufacturing, assembly and packing, transport, Earth and space exploration, surgery, weaponry, laboratory research, and mass production of consumer and industrial goods.

By the very end of the decade, robotics had started to make advancements on the nanotechnology scale. In 2019, engineers at the University of Pennsylvania created millions of nanobots in just a few weeks using technology borrowed from the mature semiconductor industry. These microscopic robots, small enough to be injected into the human body and controlled wirelessly, could one day deliver medications and perform surgeries, revolutionizing medicine and health.[131]

See also

- History of artificial intelligence

- History of computing hardware

- History of mass production

- Numerical control

Notes

- ^ "Kourai Khryseai". Theoi Project. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-19-925616-7. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

- ISBN 978-1-4384-3455-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4384-3455-1.

- ISBN 978-1-4384-3455-1.

- ISBN 978-1-4384-3455-1.

- ISBN 978-1-4384-3455-1.

- ISBN 978-0-691-11764-5.

- ISBN 978-0-691-18544-6.

- ^ a b William Godwin (1876). "Lives of the Necromancers".

- ^ Haug, "Walewein as a postclassical literary experiment", pp. 23–4; Roman van Walewein, ed. G.A. van Es, De Jeeste van Walewein en het Schaakbord van Penninc en Pieter Vostaert (Zwolle, 1957): 877 ff and 3526 ff.

- ^ See also P. Sullivan, "Medieval Automata: The 'Chambre de beautés' in Benoît's Roman de Troie." Romance Studies 6 (1985): 1–20.

- ^ Currie, Adam (1999). "The History of Robotics". Archived from the original on 18 July 2006. Retrieved 10 September 2007.

- ISBN 978-0-415-63121-1.

- ISBN 978-0-415-63121-1.

- ISBN 0-271-01670-1. Records Liutprand's description.

- ^ "Su Song's Clock: 1088". Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-319-20645-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-319-20645-5.

- ISBN 978-0-415-63121-1.

- ^ al-Jazari (Islamic artist), Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Donald Hill (1996), A History of Engineering in Classical and Medieval Times, Routledge, p. 224

- History, archivedfrom the original on 12 December 2021, retrieved 6 September 2008

- ISBN 978-0-471-02622-8

- ^ "articles58". 29 June 2007. Archived from the original on 29 June 2007. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ISBN 978-0-471-02622-8

- ISBN 978-0-415-63121-1.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-415-63121-1.

- ^ Truitt, Elly R. "The Garden of Earthly Delights: Mahaut of Artois and the Automata at Hesdin". Iowa Research Online, University of Iowa. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- ^ PMID 17206888.

- ^ a b "Sir Richard Arkwright (1732–1792)". BBC. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-319-20645-5.

- ISBN 978-3-319-20645-5.

- ISBN 978-0-8166-2697-7.

- ^ T. N. Hornyak (2006). Loving the Machine: The Art and Science of Japanese Robots. Kodansha International.

- ISBN 978-0-313-33168-8.

- ^ Gizycki, Jerzy. A History of Chess. London: Abbey Library, 1972. Print.

- ISBN 978-0-7456-3954-3.

- ^ Sarkar 2006, page 97

- ^ A. P. Yuste. Electrical Engineering Hall of Fame. Early Developments of Wireless Remote Control: The Telekino of Torres-Quevedo,(pdf) vol. 96, No. 1, January 2008, Proceedings of the IEEE.

- ^ H. R. Everett, Unmanned Systems of World Wars I and II, MIT Press - 2015, pages 91-95

- ^ "1902 – Telekine (Telekino) – Leonardo Torres Quevedo (Spanish)". 17 December 2010.

- ISBN 978-1-317-50381-1.

- ^ Brian Randell, From Analytical Engine to Electronic Digital Computer: The Contributions of Ludgate, Torres and Bush. Annals of the History of Computing, Vol. 4, No. 4, Oct. 1982

- ^ Hooper & Whyld 1992 page 22. The Oxford Companion to Chess (2nd ed.). England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866164-9.

- ^ L. Torres Quevedo. Ensayos sobre Automática - Su definicion. Extension teórica de sus aplicaciones, Revista de la Academia de Ciencias Exacta, Revista 12, pp.391-418, 1914.

- ^ Torres Quevedo. L. (1915). "Essais sur l'Automatique - Sa définition. Etendue théorique de ses applications", Revue Génerale des Sciences Pures et Appliquées, vol. 2, pp. 601–611.

- ^ B. Randell. Essays on Automatics, The Origins of Digital Computers, pp.89-107, 1982.

- OCLC 52197627.

- ISBN 978-3-319-20645-5.

- ^ "R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots)". Archived from the original on 26 August 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- ^ Asimov, Isaac; Frenkel, Karen (1985). Robots: Machines in Man's Image. New York: Harmony Books. p. 13.

- ^ "The checkered history of automation". newatlas.com. 10 November 2008. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- ^ "MegaGiantRobotics". Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- ^ "AH Reffell & Eric Robot (1928)". Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-313-33168-8.

- ^ "Robot Dreams : The Strange Tale of a Man's Quest To Rebuild His Mechanical Childhood Friend". The Cleveland Free Times. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- ISBN 0-9785844-1-4.

- ^ "Japan's first-ever robot". Yomiuri.co.jp. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ISBN 978-1-317-10912-9.

- ISBN 978-0-313-33168-8.

- ISBN 978-0-313-33168-8.

- ISBN 978-0-313-33168-8.

- ^ Owen Holland. "The Grey Walter Online Archive". Archived from the original on 9 October 2008. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- ^ "George Devol Listing at National Inventor's Hall of Fame".

- ^ Waurzyniak, Patrick (July 2006). "Masters of Manufacturing: Joseph F. Engelberger". Society of Manufacturing Engineers. 137 (1). Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- ISBN 978-3-319-20645-5.

- ISBN 978-0-313-33168-8.

- ISBN 978-0-313-33168-8.

- ^ "Robot Hall of Fame – Unimate". Carnegie Mellon University. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 28 August 2008.

- ^ Mickle, Paul. "1961: A peep into the automated future", The Trentonian. Accessed 11 August 2011.

- ^ "National Inventor's Hall of Fame 2011 Inductee". Invent Now. Archived from the original on 4 November 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f "Computer History Museum – Timeline of Computer History". Retrieved 30 August 2007.

- ISBN 978-3-319-20645-5.

- ISBN 978-1-317-10912-9.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-317-10912-9.

- ^ Robotics and Mechatronics: Proceedings of the 4th IFToMM International Symposium on Robotics and Mechatronics, page 66

- ^ "Humanoid History -WABOT-".

- ^ Robots: From Science Fiction to Technological Revolution, page 130

- ^ Handbook of Digital Human Modeling: Research for Applied Ergonomics and Human Factors Engineering, Chapter 3, pages 1-2

- ^ "Edinburgh Freddy Robot". Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- ^ "first industrial robot with six electromechanically driven axes KUKA's FAMULUS". Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- ^ "1960 - Rudy the Robot - Michael Freeman (American)". cyberneticzoo.com. 13 September 2010. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ The Futurist. World Future Society. 1978. pp. 152, 357, 359.

- ^ Colligan, Douglas (30 July 1979). The Robots Are Comming. New York Magazine.

- ^ "The Robot Hall of Fame : AIBO". Archived from the original on 6 September 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- ^ "Robotics Institute: About the Robotics Institute". Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- ^ "Cobot - collaborative robot". peshkin.mech.northwestern.edu.

- ^ "Takeo Kanade Collection: Envisioning Robotics: Direct Drive Robotic Arms". Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- ^ "2history". Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- ^ "P3". Honda Worldwide. Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- hdl:1721.1/14531.

- ^ "Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control: A Robot Invasion of The Solar System" (PDF). Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- ISBN 978-1-4666-7388-5.

- ^ "Something's Fishy about this Robot". Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- ^ "ASIMO". Honda Worldwide. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- ^ "The Robot Hall of Fame : Mars Pathfinder Sojourner Rover". Archived from the original on 7 October 2007. Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- ^ "The Honda Humanoid Robots". Archived from the original on 11 September 2007. Retrieved 10 September 2007.

- ^ "AIBOaddict! About". Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 10 September 2007.

- ^ "ASIMO". Honda Worldwide – Technology. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 10 September 2007.

- ^ Williams, Martyn (21 November 2000). "Technology – Sony unveils prototype humanoid robot – November 22, 2000". CNN. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ^ "NASA – Canadarm2 and the Mobile Servicing System". Archived from the original on 23 March 2009. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ^ "Global Hawk Flies Unmanned Across Pacific". Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ^ "Maid to Order". Time. 14 September 2002. Archived from the original on 13 August 2007. Retrieved 15 September 2007.

- ^ Breazeal, Cynthia. "Robots that Imitate Humans". MIT Media Lab. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ISBN 978-0-19-516619-4, retrieved 8 October 2024

- ^ "Self-replicating blocks from Cornell University". YouTube. Archived from the original on 12 December 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ "Mars Opportunity Rover Mission: Status Reports". Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ "Robots fail to complete Grand Challenge – Mar 14, 2004". CNN. 6 May 2004. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ^ "Honda Debuts New ASIMO". Honda Worldwide. 13 December 2005. Archived from the original on 20 July 2012. Retrieved 15 September 2007.

- ^ "Cornell CCSL: Robotics Self Modeling". Retrieved 15 September 2007.

- ^ "Robonaut | NASA". Nasa.gov. 9 December 2013. Archived from the original on 6 November 2010. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ Snider, Mike. "Boston Dynamics' latest robot video shows its 5-foot humanoid robot has moves like Simone Biles". USA TODAY. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "Months after launch, the DJI Mavic 3 is a much better drone". Engadget. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "Amazon Prime Air prepares for drone deliveries". US About Amazon. 13 June 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "TensorFlow". TensorFlow. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "Lane Departure Warning & Lane Keeping Assist". Consumer Reports. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "Tesla Autopilot Archives". Electrek. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "Tesla cars on autopilot have stopped on highways without cause, owners report". the Guardian. Associated Press. 3 June 2022. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ISSN 1059-1028. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "AI emotion-detection software tested on Uyghurs". BBC News. 25 May 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ Guariglia, Jason Kelley and Matthew (15 July 2022). "Ring Reveals They Give Videos to Police Without User Consent or a Warrant". Electronic Frontier Foundation. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- S2CID 53023323.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia gives citizenship to a non-Muslim, English-Speaking robot". Newsweek. 26 October 2017.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia bestows citizenship on a robot named Sophia". TechCrunch. 26 October 2017. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia takes terrifying step to the future by granting a robot citizenship". AV Club. 26 October 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia criticized for giving female robot citizenship, while it restricts women's rights". ABC News. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ^ "Westworld review – HBO's seamless marriage of robot cowboys and corporate dystopia". the Guardian. 5 October 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "About us". Archived from the original on 9 January 2014.

- ^ Douglas, Jacob. "These American workers are the most afraid of A.I. taking their jobs". CNBC. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- Cosmos Magazine. Archived from the originalon 8 March 2019. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

References

- Haug, Walter. "The Roman van Walewein as a postclassical literary experiment." In Originality and Tradition in the Middle Dutch Roman van Walewein, ed. B. Besamusca and E. Kooper. Cambridge, 1999. 17–28.

Further reading

- Balafrej, Lamia (2022). "Automated Slaves, Ambivalent Images, and Noneffective Machines in al-Jazari's Compendium of the Mechanical Arts, 1206". 21: Inquiries into Art, History, and the Visual. 3 (4): 737–774. ISSN 2701-1569.

- Baumgartner, Emmanuèlle. "Le temps des automates." In Le Nombre du temps, en hommage à Paul Zumthor. Paris: Champion, 1988. pp. 15–21.

- Brett, G. "The Automata in the Byzantine 'Throne of Solomon'." Speculum 29 (1954): 477–87.

- Glaser, Horst Albert and Rossbach, Sabine: The Artificial Human, Frankfurt/M., Bern, New York 2011 "The Artificial Human. A Tragical History", ebook "The Artificial Humans. A Real History of Robots, Androids, Replicants, Cyborgs, Clones and all the rest"

- Sullivan, P. "Medieval Automata: The 'Chambre de beautés' in Benoît's Roman de Troie." Romance Studies 6 (1985). pp. 1–20.

- History of Robots in 10 Minutes. Archived 20 October 2022 at the Wayback Machine